Thought-Forms (book)

2nd reprint title page, 1905 | |

| Authors | A. Besant, C. W. Leadbeater |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Theosophy |

| Publisher | Theosophical Publishing Society |

Publication date | 1901 |

| Pages | 84 |

| OCLC | 59773169 |

| Text | Thought-Forms online |

Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation is a theosophical book compiled by the members of the Theosophical Society A. Besant and C. W. Leadbeater. It was originally published in 1901 in London.[1][2] From the standpoint of Theosophy, it tells regarding visualization of thoughts, experiences, emotions and music. Drawings of the "thought-forms" were performed by painters Varley, Prince, and McFarlane.[3][note 1]

From history of compilation

This book has become the result of the joint work of the authors, which began in 1895, when they had started an investigation of "the subtle matter of the universe."[8] They were interested the work of the human mind as, according their claim, this work "extrudes into the external world" the thought-forms.[9]

In September 1896, Besant reported in Lucifer that "two clairvoyant Theosophists" (whose personalities were not disclosed in the journal, although some members of the Society knew about them) had started "observing the substance of thought." Her article named Thought-Forms[note 2] was accompanied by four pages of pictures of diverse thought-forms which the investigators "had observed and described to an artist."[9][note 3] The colour sketches of the unknown performance were depicting: on the first plate—thought-forms of "devotion," "sacrifice," and "devotional," on the second one—three types of "anger," on the third one—three types of "love" ("undirected," "directed," and "grasping"), and on the fourth one—thought-forms of "jealousy," "intellect," and "ambition."[13] Besant gave the article scientific coloring, not forgetting to mention Röntgen, Baraduc,[14] Reichenbach, "vibrations and the ether."[9]

This "small but influential book",[note 4] which contains color pictures of thought-forms that the authors said are created "in subtle spirit-matter," was published in 1901. The book affirms that "the quality" of thoughts influences the life experience of their creator, and that they "can affect" other people.[16][note 5]

Basic concepts

Meaning of color

The authors write that they, like many theosophists, are convinced that "thoughts are things," and the task of their book is to help the reader understand this.[18][note 6] The frontispiece of the book contains a table "The meanings of colours" of thought-forms and human aura associated with feelings and emotions, beginning with "High Spirituality" (light blue—in the upper left corner) and ending by "Malice" (black—in the lower right corner), 25 colors in all.[note 7][19][22][note 8] The authors argue that human aura is "the outer part of the cloud-like substance of his higher bodies, interpenetrating each other, and extending beyond the confines of his physical body."[24] The mental and desire bodies (two human higher bodies) are "those chiefly concerned with the appearance of what are called thought-forms."[25][note 9][note 10][note 11]

Three principles and three classes

The book states that "the production of all thought-forms" is based on three major principles:

The authors define the following three classes of thought-forms:

- That which takes the image of the thinker. When a man thinks of himself as in some distant place, or wishes earnestly to be in that place, he makes a thought-form in his own image which appears there.

- That which takes the image of some material object. [The painter who forms a conception of his future picture builds it up out of the matter of his mental body, and then projects it into space in front of him, keeps it before his mind's eye, and copies it. The novelist in the same way builds images of his character in mental matter, and by the exercise of his will moves these puppets from one position or grouping to another, so that the plot of his story is literally acted out before him.][note 14]

- That which takes a form entirely its own,[note 15] expressing its inherent qualities in the matter which it draws round it. [Those of which we here give specimens are almost wholly of that class.][39][40]

Examples of thought-forms

"To paint in earth's dull colours the forms clothed in the living light of other worlds, — Besant writes in the foreword, — is a hard and thankless task." The authors claim that the images in the book "are not imaginary forms, prepared as some dreamer thinks that they ought to appear." Rather, "they are representations of forms actually observed as thrown off by ordinary men and women." And the authors sincerely hope that they will force the reader "realise the nature and power of his thoughts, acting as a stimulus to the noble, a curb on the base."[45]

Created by emotions

In Fig. 13 shows the thought-form created by "a strong craving for personal possession." Its color has dull unpleasing hue "deadened with the heavy tint indicative of selfishness." The curving hooks are its especially characteristic. Creator this thought-form had never "conception of the self-sacrificing love which pours itself out in joyous service," no thinking of return.[41][note 19][note 20]

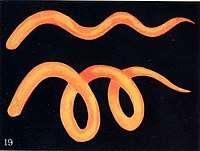

The authors write that a form in Fig. 19 at the top is a specific thought-form which had accompanied a question demonstrating deep thought and penetration. The first variant of the answer did not fully satisfy the questioner, and his desire to achieve a full and comprehensive answer was expressed in the fact that his "thought-form deepened in colour and changed into the second of the two shapes (in Fig. 19 below), resembling a corkscrew even more closely than before."[53][note 22][note 23]

Fig. 22 and 23 are thought-forms of a "murderous rage" (on the right) and a "sustained anger" (on the left). The first form was taken "from the aura of a rough and partially intoxicated man in the East End of London," when he was knocking down a woman; a flare flashed in her direction, triggering an explosion of horror—she recognized that one would be struck. In the same illustration drawned a "stiletto-like dart" directed to the lower left corner: it is a thought "of steady anger, intense and desiring vengeance, of the quality of murder, sustained through years, and directed against a person who had inflicted a deep injury on the one who sent it forth."[56][note 25][note 26]

The authors state that when a person is suddenly frightened, then has a place the effect shown in Fig. 27. It is emphasized that "all the crescents" on the right, which apparently have been emitted earlier than others, do not show anything other than "the livid grey of fear; but a moment later the man is already partially recovering from the shock, and beginning to feel angry that he allowed himself to be startled." The later crescents have changed to scarlet, and it evidences the "mingling of anger and fear," while the last crescent is quite scarlet, and it shows that "already the fright is entirely overcome, and only the annoyance remains."[60][note 30]

Created by experiences

Beginning from Fig. 30, "the book changes course in an interesting way," moving from the illustrations of individual thoughts and emotions to the narrative of events.[64] Besant and Leadbeater write that occasioned by a "terrible accident" at sea, three thought-forms depicted in Fig. 30 "were seen simultaneously, arranged exactly as represented, though in the midst of indescribable confusion." The authors continue:

"They are instructive as showing how differently people are affected by sudden and serious danger. One form [on the right] shows nothing but an eruption of the livid grey of fear, rising out of a basis of utter selfishness: and unfortunately there were many such as this. The shattered appearance of the thought-form shows the violence and completeness of the explosion, which in turn indicates that the whole soul of that person was possessed with blind, frantic terror, and that the overpowering sense of personal danger excluded for the time every higher feeling."[65]

The authors explain that the thought-form in Fig. 30 on the left shows an attempt to find "solace in prayer," and in this way overcome fear. This can be seen under a grayish-blue color, "which lifts itself hesitatingly upwards." Yet it is seen that judging by "the lower part of the thought-form, with its irregular outline and its falling fragments, that there is in reality almost as much fright here" as in the case on the right. Thus, one person has a chance to restore "self-control," while the other remains "an abject slave to overwhelming emotion." The thought-form at upper has been created by a member of the ship crew responsible for the lives of passengers, and it demonstrates a "very striking contrast" of the weakness manifesting in two forms from below. Herein shown "a powerful, clear-cut and definite thought, obviously full" of energy and determination. Orange color speaks of his confidence in ability to manage with the difficulty. The "brilliant yellow" means that his intellect is already at work upon the problem.[68][note 33]

Fig. 31 is another declarative piece, depicting "the thought-form of an actor while waiting to go upon the stage." The authors expound that the orange band indicates self-confidence,

"yet in spite of this there is a good deal of unavoidable uncertainty as to how this new play may strike the fickle public, and on the whole the doubt and fear overbalance the certainty and pride, for there is more of the pale grey than of the orange, and the whole thought-form vibrates like a flag flapping in a gale of wind." [70][note 35]

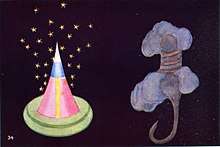

In the thought-form on the left in Fig. 34, as the authors explain, there is nothing but "the highest and most beautiful" feelings. At the base of the thought-form, you can see "a full expression of deep sympathy," the light green color shows the understanding of the suffering of the deceased's relatives and condolence with them, and the strip "of deeper green shows the attitude of the thinker towards the dead man himself." The dense rose-color shows love to both the deceased and the surrounding, while the upper part, consisting of a cone and stars above it, indicates a feeling in connection with thoughts of death: the blue express "its devotional aspect," while as "the violet shows the thought of, and the power to respond to, a noble ideal" and the ability to match, the stars reflect "the spiritual aspirations."[73][note 37] In the same figure, the thought-form on the right reflects nothing but only "profound depression, fear and selfishness." His only definite feelings are despair and the sense of his personal loss, and these show themselves in proper strips of brown-grey and leaden grey color, while the "very curious downward protrusion" demonstrates the strong selfish desire to raise the dead man into his earth life.[73][note 38][note 39]

Created by meditation

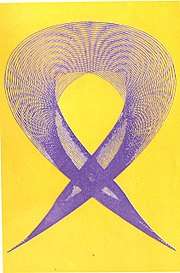

The description of the event depicted in the book on Fig. 38, as noted a historian Breen, "anticipates the 1960s" as well with its conjunction of meditation and idealism: this thought-form was "generated by one who was trying, while sitting in meditation, to fill his mind with an aspiration to enfold all mankind in order to draw them upward towards the high ideal which shone so clearly before his eyes."[77] The ability of the authors to see the "vibrations of ideas, emotions, and sounds" demonstrates, in his opinion, "a sort of spiritual synesthesia" which transform the religious act into a neurological phenomenon.[78]

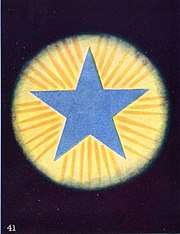

The authors write that the thought-form shown in Fig. 41 was accompanied by "the devotional aspiration" to that Logos may thus be manifested through the man in meditation. It is this religious feeling gives a "pale blue" shade to the five-pointed star. This form has been used "for many ages as a symbol of God manifest in man."[80][note 42][note 43][note 44]

Created by music

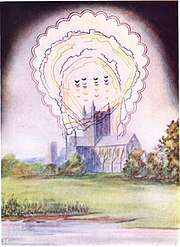

Plate M showing the form created by music of Mendelssohn "depicts yellow, red, blue and green lines rising out of a church." This, as the authors explain, "signifies the movement of one of the parts of the melody, the four moving approximately together denoting the treble, alto, tenor and bass respectively." Moreover, "the scalloped edging surrounding the whole is the result of various flourishes and arpeggios, and the floating crescents in the centre represent isolated or staccato chords."[85][note 47]

On Plate G depicts a musical form to the piece by Gounod.[87][note 48] Describing a musical form "created" by Wagner (on Plate W), the authors note in it the likeness to the "successively retreating" ramparts of a mountain, "and it is heightened by the billowy masses of cloud which roll between the crags and give the effect of perspective."[88][note 49][note 50]

Thought-Forms and modern arts

According to professor Ellwood, the book by Besant and Leadbeater had a large influence on modern art. "It suggested, to a world moving rapidly beyond the literalism of Victorian art, the expression in painting of surreal forms and forces underlying, but different from, the visible world."[92] Thought-Forms demonstrated how the symbolism of "astral colors and forms" can express the specificity of "certain soul's and mental states." It had a great influence on Kandinsky[93][19][note 52] as one of the essential factors that led to the "genius opening of new perspectives for painting."[96][note 53][note 54]

According to reminiscences by Sabaneyev, besides The Secret Doctrine Scriabin interested a magazine Vestnik Theosofii, which published [from 1908] the translations of Besant and Leadbeater's works.[99][100] Apparently, being impressed by theirs theosophical works, he once said that "strong, powerful thought creates a thought-form so intense that it, in addition to the will, flows into the consciousness of other people."[101][note 55] The perform of the part of light in Prometheus he imagined in the form of a radiance of some "luminous matter," which was supposed to fill the hall.[103][note 56][note 57]

A historian Breen wrote that Besant and Leadbeater were well aware how annoying stuff may be their book for a "society that remained deeply conservative." In early January 1901, when this book was published, "Queen Victoria still ruled England. 'Modernism' as a movement or even a concept did not exist. When we consider this world of 1901, – further wrote Breen, – it becomes difficult not to believe that Besant, Leadbeater and their milieu deserve a more prominent place in the annals of both abstract art and the history of modernism." As the art critic Kramer has pointed, "what is particularly striking about the outlook of the artists primarily responsible for creating abstraction is their espousal of occult doctrine."[76] Yeats, Eliot, Malevich, Kandinsky, and Mondrian were charmed by Theosophy.[note 58] In the first decades of the twentieth century, it was a widespread "component of Western cultural life."[106][note 59]

Thus, Besant and Ledbetter had played, summed up Breen, "a small but intriguing role in shaping the globalized culture... which weaves together East and West, mysticism and rationalism, sound and sight."[107][note 60]

Criticism

An academic science names the activities of such "investigators," as the authors of this book, "pseudoscience", because it based on a concept of the extrasensory perception.[110] The belief in existence of thought-forms "remains influential today" for the Theosophists, followers of New Thought, New Age and in neopagan movements, including Wicca.[111][112]

New editions and translations

After its first publication in 1901 the book was reprinted several times (8th – in 1971).[113] This work has been translated into several European languages: French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish.[note 61][note 62]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Trefilov, Theosophy, unlike an academic science, "views the whole world as a manifestation of thought in all categories of matter. Occult science know about the existence of higher types of rarefied matter. Man is in no way limited by the physical world alone."[4] Radhakrishnan wrote, "There are other worlds than that which our senses reveal to us, other senses than those which we share with the lower animals, other forces than those of material nature."[5] Thus, it is necessary to develop the "new senses" in order to "perceive thought-forms."[6] Academic science explains the visualization of sensations of a mentally healthy person by a phenomenon of the synesthesia.[7]

- ↑ Leadbeater does not appear here as a co-author of Besant, nevertheless, according to Hammer, after Blavatsky's death, it was he who became the main ideologist of the "second generation" of the Theosophists.[10]

- ↑ A tradition of "seeing thoughts" already existed in spiritualism. Dr. Baraduc, a famous French psychiatrist, had informed the "Acadamie de Medecine" in 1896 that he had succeeded to photograph thoughts.[11][12]

- ↑ According to the scholars of religious studies, the authors of the Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America.[15]

- ↑ As Leadbeater noted, "books are specially strong centres of thought-forms, and their unnoticed influence in a man's life is often a powerful one."[17]

- ↑ Lachman noted that it is "the central maxim of Thought-Forms."[19]

- ↑ See the frontispiece of Thought-Forms, 1901. For comparison, see table "Auric Colors and Their Meanings"[20] and Ch. "Colours."[21]

- ↑ "Every thought form bears the same color that it would possess if it had been retained in the body of the aura itself."[23]

- ↑ Ellwood wrote that, according to theosophy, "auras may be made up of a complex combination of etheric, astral, and mental matter which the clairvoyant is able to perceive, although the most significant ones originate on the border of the mental and astral planes, where the activity of the former is reflected in the configurations of astral matter. When comparable patterns appear as a 'cloud' above or near a person, they may be called 'thought-forms' and as such have been reported in theosophical literature."[26]

- ↑ Thought-forms are created from the same matter from which the aura is formed, and have the same general properties, in particular, color. Knowledge of the properties of an aura of man is necessary for a proper "understanding of the nature of the thought-forms."[27] According to Powell, the term "thought-forms" is "not wholly accurate," because in the overwhelming majority of cases they are being formed by both astral and mental bodies. It would be more correct to call them thought-emotion forms.[28] Gettings wrote that in studying the illustrations from this book "one cannot help observing that they do not really relate to thought so much as to feeling – they are really emotion forms rather than thought forms."[29]

- ↑ According to Tillett, "Whether or not there is scientific validity in claims about the aura, it remains significant that Leadbeater's descriptions (given initially in an article [The Aura] in The Theosophist in [December] 1895[30]) have been more or less repeated by later researchers, both scientific and occult. The earliest scientific study of the aura [The Human Atmosphere, 1911] was published by Walter John Kilner."[31]

- ↑ Bailey has contraposed the "clear and well-defined, pulsating with the spirit of service" thought-forms of the initiated occultist with the "disjointed, unconnected, and uncorrelated" thought-forms created by the "mass of men."[33] As Powell wrote, many people go through life, literally tightly locked in their own cells, which they themselves have built, "surrounded by masses of forms created by their habitual thoughts."[34] Leadbeater noted later that most people can not free themselves from the influence "of the great crowd of thought-forms which constitute [preconceived] public opinion; and because of those they never really see the truth at all."[35]

- ↑ "Thought-forms, or 'an artificial elementals,' have a huge impact on the earthly life of people, performing certain functions depending on the desires and direction of the thought that created them."[36]

- ↑ A comparison of the thought-forms of literary heroes with marionettes, Leadbeater repeated in 1913 in his next Theosophical book.[37]

- ↑ Pisareva wrote that the thought-forms belonged to this category may be named the "symbolic forms."[38]

- ↑ It's like "a pale blue lotus."[42] Blue color expresses "spirituality."[43] "A thought of definite, well-sustained devotion may assume a form closely resembling a flower."[44] The more purified desires and thoughts of man, the more "radiant and beautiful" are his thought-forms which he create.[19]

- ↑ It's like "brown-red swirls."[9] "Thoughts of a greedy, lustful, or malicious character appear differently from those of a noble, selfless, loving nature."[19]

- ↑ "Thoughts in which selfishness or greed are prominent usually take a hooked form, the hooks in some case actually clawing round the object desired."[47] Leadbeater has compared similar thought-forms with the "grappling hooks."[48]

- ↑ Tillett saw here only the "brown-red swirls."[9] An especially powerful class of this kind of thought-forms takes on "the appearance of a nebulous octopus, with long, winding, clinging tentacles, striving to wrap around the other person," and to drag him toward the aura of creator.[49]

- ↑ "A gross sensual love will be a dull and heavy crimson"... The mutual influence of thoughts is like "adding fuel to the fire." If someone for a long time is fraught with low thoughts, then into his mind will pour such a vicious stream that he will be horrified if he understands what he is doing with himself.[50] According to Leadbeater, do not need to collect photos of actresses [and actors], as "they always attract the most undesirable thought-forms from hosts of impure-minded people."[17]

- ↑ "I asked him when he saw this curious shape."[52]

- ↑ Jinarajadasa informed that on his question to Leadbeater "when he saw this curious shape" he answered that it is a creation of Mr. Sinnett, "who tried to 'worm' things out of him, when he appeared to be holding back some knowledge which Mr. Sinnett wanted."[52]

- ↑ "Orange, of a bright shade, represents pride and ambition. Yellow, in its various shades, represents intellectual power."[54] Gold colour "indicates pure intellect applied to philosophy or mathematics."[55]

- ↑ It's like "a bright red spike."[57]

- ↑ Tillett has seen on the left "a bright red spike."[9] Sustained anger takes the form of "a sharp, red stiletto."[58] The thought-form of anger has a color of black and red, with characteristic flares.[23]

- ↑ Red color seen in the form of bright red flares like the lightning flash shows anger. These are "usually shown on a black background in the case of anger arising from hatred or malice."[59]

- ↑ It's like "a cloud of red-grey crescents."[42] "Sudden Fright appears as a series of grey and red crescent shapes bursting out of the aura."[19]

- ↑ "The craving for alcohol produced undesirable brown-red hooks."[42]

- ↑ "The thought of the desire for drink could not enter the body of a purely temperate man. It would strike upon his astral body, but it could not penetrate and it would then return to the sender."[62]

- ↑ According to Tillett, here you can see "a cloud of red-grey crescents."[42] Gray color of a specific shade, "almost that of a corpse", demonstrates "fear and terror." Red color shows anger.[63]

- ↑ It's like "a grey-brown cloud [on the right]."[42]

- ↑ According to Lachman, the illustrations of thought-forms in the book are "very reminiscent of much abstract and surrealistic painting."[19] "This ushers in the visual heart of the book, featuring images that wouldn't look out of place hanging alongside early Malevich or Kandinsky abstractions."[67]

- ↑ Gray color of a specific shade demonstrates "fear and terror." Orange of a "bright shade, represents pride and ambition." Yellow, in its diverse tones, shows "intellectual power."[69]

- ↑ "Figure 31 is another narrative piece."[67]

- ↑ Gray color represents fear. Bright orange shows "pride and ambition."[69]

- ↑ "The highly contrasting pair of thought forms observed by a clairvoyant at a funeral."[72] "The atmosphere at a funeral [two forms]."[42]

- ↑ According to Gettings, the thought-form to the left is a spiritual one "which was a result of the highest meditation in the face of the loss of the loved one."[29] "Pale, luminous blue-green" shows deep sympathy and compassion. "Luminous lilac-blue, usually accompanied by sparkling golden stars" is associated with a high level of spirituality and noble aspirations. Rose color expresses selfless love.[55]

- ↑ Dark gray color represents "depression and melancholy."[63]

- ↑ Gettings wrote that the form to the right demonstrates a distress of the materialist forming from the mind of one "who is unable to accept that death is a liberation into a higher world, and the proboscis-like feeler which runs from the base of this thought form is said to be reaching into the grave, as if to bring back the dead body."[29] "The man who had lived in the ordinary blank ignorance with regard to death, had no thought in connection with it but selfish fear and depression; whereas the man who understood the facts was entirely free from any suggestion of those feelings, for the only sentiments evoked in him were those of sympathy and affection for the mourners, and of devotion and high aspiration."[74]

- ↑ "Figure 38 is even more radical a departure, anticipating the op art of the 1960s."[76]

- ↑ "It looks like more like logos as manifested by ad men."[67]

- ↑ Thought-forms created by men who have "mind and emotion well under control and definitely trained in meditation, are clear, symmetrical objects."[58] Light blue color, of a "peculiarly clear and luminous shade, represents spirituality."[43]

- ↑ According to Breen, this thought-form looks like a kind of logos in advertising: it can be easily taken as an old oil company sign, "competing with Esso, British Petroleumand Royal Dutch Shell."[81] Nevertheless, according to Bailey, our solar system is the manifested "thought-form" of its Logos.[82]

- ↑ The diversity of guises of thought-forms is almost endless. Each combination of thought and feeling builds its own form, and each man "seems to have his own peculiarities in this respect."[23]

- ↑ "Color and sound had become commingled."[78]

- ↑ Forms created by music, strictly speaking, are not thought forms, but, nevertheless, they do not arise without "the thought of the composer".[58] Later, Leadbeater explained that mental, astral and etheric structures are built up "by the influence of sound," and that "forms, created by the performers of the music, must not be confounded with the magnificent thought-form which the composer himself made as the expression of his own music in the higher worlds."[84]

- ↑ Lachman named the musical forms of Besant and Leadbeater "the synaesthetic forms created by music."[19] In the first part of her article Occult or Exact Science? Blavatsky described in detail the multiple phenomena of color-sound vision.[86]

- ↑ See it here: Thoughtform#Thoughtform

- ↑ According to Tillett, Wagner "produced weird mountains in pink, green and red."[42] Powell wrote that the overture by Wagner builds "mountains of flame." [89]

- ↑ See some more musical forms to the works of Wagner in the book by Hodson.[90]

- ↑ "The organ music of Wagner, seen on the astral plane."[72] It's like "weird mountains in pink, green and red."[42]

- ↑ The ideas which Kandinsky "elaborated in numerous notes and articles, including the now iconic text On the Spiritual in Art, were a combination of Besant and Leadbeater's theories on thought-forms, Steiner's considerations of colour, music, and vibration, [and] theories about synaesthesia."[94] Kandinsky "owned a German translation" (1908 edition) of the book Thought-Forms.[95]

- ↑ According to Lachman, one Kandinsky's painting in which the "influence of Thought-Forms is quite visible" is Woman in Moscow (1912).[19] Also one of Kandinsky's paintings "is similar" to the musical form from the book of Besant and Leadbeater.[97]

- ↑ According to Jones, two Leadbeater's books are "relevant to Kupka's search for the immaterial: Clairvoyance (1899) and Thought-Forms (1901), co-written with Besant."[98]

- ↑ According to an Ukrainian philosopher Julia Shabanova, a book Thought-Forms was being "discussed" by Alexander Scriabin and Jean Delville, a Belgian symbolist painter.[102]

- ↑ "Scriabin introduced many Theosophical ideas into his compositions and also experimented with 'synesthesia,' the strange experience of 'hearing colors' and 'seeing music'."[104]

- ↑ See also: Clavier à lumières

- ↑ Beckmann who was "impressed" by the book The Secret Doctrine he read in 1934 made several different sketches "on the theme" of its second volume Anthropogenesis. The album with these sketches is in the Washington National Gallery.[105]

- ↑ "Oppenheimer famously quoted Vedic scripture... when he witnessed the first atomic bomb blast. But in the context of figures like Besant and Ledbetter, Oppenheimer's fascination with Eastern mysticism seems less like a personal quirk and more like a thread in a larger tapestry: an interweaving of mysticism, technology, and art that began at the turn of the last century and is still with us in the twenty-first."[107]

- ↑ According to Goldman, Presley interested the books by Blavatsky "and those of her disciples" Besant and Leadbeater.[108] Leadbeater's Inner Life has belonged to his favourite books, and he often read from it "aloud before going on stage to perform."[109]

- ↑ See, for example, OCLC: 468751993, 699107177, 955597141, 940052686, 777895008.

- ↑ "63 editions published between 1901 and 2011 in... languages and held by 649 WorldCat member libraries worldwide."[114]

References

- ↑ Melton 2001b, p. 1566.

- ↑ Goodrick-Clarke 2008, p. 248.

- ↑ Gettings 1978, p. 136; Tillett 1986, p. 224.

- ↑ Трефилов 1994, p. 234.

- ↑ Radhakrishnan 2008, p. 373.

- ↑ Ellwood 1986, p. 117.

- ↑ Britannica.

- ↑ Wessinger.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tillett 1986, p. 224.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 509.

- ↑ Melton 2001b, p. 1565.

- ↑ Tillett 1986, p. 990.

- ↑ Index.

- ↑ Melton 2001a.

- ↑ Keller 2006.

- ↑ Keller 2006, p. 755.

- 1 2 Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 15.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lachman 2008.

- ↑ Ramacharaka 2007, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Powell 1927, Ch. 3.

- ↑ Писарева 2010, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Atkinson 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 17; Johnston 2012, p. 158.

- ↑ Ellwood 1986, p. 115.

- ↑ Atkinson 2011, p. 31.

- ↑ Powell 1927, pp. 43, 55.

- 1 2 3 Gettings 1987, p. 47.

- ↑ IndexT.

- ↑ Tillett 1986, p. 953.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 31; Писарева 2010, p. 29; Jones 2012, p. 54.

- ↑ Bailey 2012, p. 87.

- ↑ Powell 1927, p. 47.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 10.

- ↑ Трефилов 1994, p. 237.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 6.

- ↑ Писарева 2010, p. 27.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 36; Писарева 2010, p. 26.

- ↑ Harris.

- 1 2 TForms 1901, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tillett 1986, p. 225.

- 1 2 Ramacharaka 2007, p. 66.

- ↑ Powell 1927, p. 57.

- ↑ TForms 1901, pp. 6, 39; Breen 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 43.

- ↑ Powell 1927, p. 56.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 8.

- ↑ Atkinson 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Ramacharaka 2007, pp. 65, 84.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 51; Gettings 1987, p. 48; Breen 2014, p. 112.

- 1 2 Jinarajadasa 2003.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 51.

- ↑ Ramacharaka 2007, p. 65.

- 1 2 Powell 1927, p. 12.

- 1 2 TForms 1901, p. 53.

- ↑ Tillett 1986, pp. 224–225.

- 1 2 3 Powell 1927, p. 58.

- ↑ Ramacharaka 2007, pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 TForms 1901, p. 55.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 56.

- ↑ Powell 1927, p. 49.

- 1 2 Ramacharaka 2007, p. 64.

- ↑ Breen 2014, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 57; Breen 2014, p. 112.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 58; Breen 2014, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Breen 2014, p. 112.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 57.

- 1 2 Ramacharaka 2007, pp. 64, 65.

- 1 2 TForms 1901, p. 59; Breen 2014, p. 112.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 62; Gettings 1987, p. 48.

- 1 2 Gettings 1979, p. 137.

- 1 2 TForms 1901, p. 62.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 11.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 67; Breen 2014, p. 114.

- 1 2 Breen 2014, p. 113.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 67; Breen 2014, p. 113.

- 1 2 Breen 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 69; Breen 2014, p. 113.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 69.

- ↑ Breen 2014, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Bailey 1925, p. 556.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 78.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, Ch. 8, 9.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 77; Breen 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1956, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 80; Gettings 1987, p. 49; Breen 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 82.

- ↑ Powell 1927, p. 59.

- ↑ Ходсон.

- ↑ TForms 1901, p. 82; Gettings 1979, p. 137.

- ↑ Ellwood.

- ↑ Kramer 1995.

- ↑ Johnston 2012, p. 159.

- ↑ Gettings 1978, p. 135.

- ↑ Бычков 2007, p. 83.

- ↑ Alvarenga 2011.

- ↑ Jones 2012, p. 51.

- ↑ Сабанеев 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Архив ВТ.

- ↑ Сабанеев 2000, p. 307.

- ↑ Шабанова.

- ↑ Сабанеев 2000, p. 70.

- ↑ Lachman 2002.

- ↑ Бычков 2009, p. 171.

- ↑ Breen 2014, pp. 113–114.

- 1 2 Breen 2014, p. 114.

- ↑ Goldman 1981, p. 366.

- ↑ Tillett 1986, p. 10.

- ↑ Carroll 2003.

- ↑ Keller 2006, pp. 755–756.

- ↑ Wessinger 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ Formats and editions.

- ↑ WorldCat.

Sources

- Keller, R. S.; Ruether, R. R.; Cantlon, M., eds. (2006). "Annie Besant". Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana University Press. pp. 755–756. ISBN 9780253346872. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- Melton, J. G., ed. (2001a). "Baraduc, Hyppolite (1850–1902)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 1 (5th ed.). Gale Group. p. 154. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ————, ed. (2001b). "Thoughtforms". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 2 (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 1564–1566. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "Formats and editions of Thought-Forms". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- "An Index to Lucifer, 1887–1897, London". Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals. The Campbell Theosophical Research Library. 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- "An Index to The Theosophist, Bombay and Adyar". Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals. The Campbell Theosophical Research Library. 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- "Leadbeater, Charles Webster 1854–1934". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Alvarenga C. (2011-07-04). "Abstract Art & Theosophy". Tradition in Action. Tradition in Action, Inc. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- Atkinson, W. W. (2011) [1912]. "Ch. VI. Thought Form". The Human Aura: Astral Colors and Thought Forms. The Floating Press. pp. 31–35. ISBN 9781775453383. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Bailey, A. (1925). A Treatise on Cosmic Fire (4th ed.). Lucis Publishing Company. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ———— (2012) [1922]. Initiation, Human and Solar (Reprint ed.). Michael Poll Publishing. ISBN 9781613420713. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Besant, A.; Leadbeater, C. W. (1901). Thought-Forms. London: Theosophical Publishing Society. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Blavatsky, H. P. (1956). "Occult or Exact Science?". In De Zirkoff, B. Collected Writings. 7. Wheaton, Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. pp. 55–90. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Breen, B. (April 2014). Breen, B., ed. "Victorian Occultism and the Art of Synesthesia". The Appendix. Austin, TX: The Appendix, LLC. 2 (2): 109–114. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Carroll, R. T. (2003). "ESP (extrasensory perception)". The skeptic's dictionary: a collection of strange beliefs, amusing deceptions, and dangerous delusions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-27242-7. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Ellwood R. S. (2012-03-15). "Leadbeater, Charles Webster". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ———— (1986). Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Wheaton, IL.: Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 9780835606073. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Gettings, Fred (1978). The hidden art: a study of occult symbolism in art. A studio vista book. Studio Vista. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ———— (1979). The Occult in Art. NY: Rizzoli. ISBN 9780847801909. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ———— (1987). Secret Symbolism in Occult Art. NY: Harmony Books. ISBN 0517567180. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Goldman, A. (1981). Elvis. McGraw-Hill Companies. ISBN 9780070236578. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Goodrick-Clarke, N. (2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-19-532099-2. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Hammer, O. (2003) [2001]. Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age (PhD thesis). Studies in the history of religions. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004136380. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Harris P. S. (2012-04-27). "Thought Forms". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Herman L. M. (2017). "Synesthesia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Jinarajadasa, C. (2003) [1938]. "Thought Forms". Occult investigations, a description of the work of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 0766130347. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Johnston, Jay (2012). "Theosophical Bodies: Colour, Shape and Emotion". In Cusack, C.; Norman, A. Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Brill. pp. 153–170. ISBN 9789004221871. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Jones, Chelsea Ann (2012). "Section II-B: Theosophy". The Role of Buddhism, Theosophy, and Science in František Kupka's Search for the Immaterial through 1909 (PDF) (M.A. thesis). Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson. Austin, Texas: University of Texas at Austin. pp. 42–55. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Kramer, H. (March 1995). Kimball, R., ed. "Kandinsky & the birth of abstraction". The New Criterion. NY: The Foundation for Cultural Review. ISSN 0734-0222.

- Lachman, G. (July 2002). "Concerto for Magic and Mysticism: Esotericism and Western Music". Quest. Theosophical Society in America. 90 (4): 132–137. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ———— (March 2008). "Kandinsky's Thought Forms and the Occult Roots of Modern Art". Quest. Theosophical Society in America. 96 (2): 57–61. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Leadbeater, C. W. (2007) [1913]. The Hidden Side of Things (Reprint ed.). New York: Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781602063228. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Powell, A. (1927). "Chapters 1–14". The Astral Body and Other Astral Phenomena. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. pp. 1–137. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Radhakrishnan, S. (2008) [1929]. Indian Philosophy (PDF). 2 (Reprint of 2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195698428. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Ramacharaka, Yogi (2007) [1903]. Fourteen lessons in Yogi philosophy. New York: Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781605200361. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Tillett, Gregory J. (1986). Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934: a biographical study (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of Sydney (published 2007). OCLC 220306221. Retrieved 10 September 2017 – via Sydney Digital Theses.

- Wessinger C. L. (2012-03-10). "Besant, Annie". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ———— (2013). "The Second Generation Leaders of the Theosophical Society (Adyar)". In Hammer, O.; Rothstein, M. Handbook of the Theosophical Current. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Boston: Brill. pp. 33–50. ISBN 9789004235960. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- in Russian

- "Архив журнала Вестник теософии" [An Archive of The Magazine "Vestnik Theosofii"]. Библиотека теософской литературы (in Russian). Теософия в России. 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- Бычков, В. В.; Иванов, В. В.; Маньковская, Н. Б. (2007). "Теософия и искусство" [Theosophy and The Arts]. Триалог. Разговор первый об эстетике, современном искусстве и кризисе культуры [Trialogue: First Talk on Aesthetics, Modern Arts and The Crisis of Culture] (PDF) (in Russian). Москва: ИФ РАН. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-5-9540-0087-0. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ————; ————; ———— (2009). "О герметизме и эзотерике в искусстве" [On Hermeticism and Esotericism in The Arts]. Триалог. Разговор второй о философии искусства [Trialogue: Second Talk on The Philosophy of The Arts] (PDF) (in Russian). Москва: ИФ РАН. pp. 154–173. ISBN 978-5-9540-0134-1. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Дружинин, Д. (2012). Блуждание во тьме: основные положения псевдотеософии Елены Блаватской, Генри Олькотта, Анни Безант и Чарльза Ледбитера [Wandering in the Dark: The Fundamentals of the Pseudo-theosophy by Helena Blavatsky, Henry Olcott, Annie Besant, and Charles Leadbeater] (in Russian). Нижний Новгород. ISBN 978-5-90472-006-3. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Писарева, Е. Ф. (2010) [1912]. Сила мысли и мыслеобразы [Thought Power and Thought Forms]. Грани познания (in Russian). Новосибирск: Россазия. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Рерих, Е. И. (2000a). "Письмо А.М. Асееву, 6 мая 1934 года" [The Letter to A.M. Aseyev, 6 May 1934]. Письма. Том II [Letters. Volume II] (in Russian). Москва: Международный Центр Рерихов. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ———— (2000b). "Письмо М.Е. Тарасову, 29 августа 1934 года" [The Letter to M.E. Tarasov, 29 August 1934]. Письма. Том II [Letters. Volume II] (in Russian). Москва: Международный Центр Рерихов. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Сабанеев, Л. Л. (2000) [1925]. Воспоминания о Скрябине [Reminiscences of Scriabin] (in Russian). Москва: Классика-XXI. ISBN 5-89817-064-2. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Трефилов, В. А. (1994). "Глава XVII: Надконфессиональная синкретическая религиозная философия" [Chapter XVII: Non-denominational syncretic religious philosophy]. In Яблоков, Игорь. Основы религиоведения. Учебник [Fundamentals of Religious Studies. Textbook] (in Russian). Москва: Высшая школа. pp. 233–245. ISBN 5-06-002849-6. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Ходсон Дж. (2017). "Музыкальные формы" [The Musical Forms]. Библиотека теософской литературы (in Russian). Теософия в России. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Шабанова Ю. А. (21 October 2016). "Идеи Е. П. Блаватской в творчестве А. Н. Скрябина" [The ideas of H.P. Blavatsky in the creation of A.N. Scriabin]. Статті Наукової групи ТТ України (in Russian). Теософское общество в Украине. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thought Forms, 1901. |