The Scorpion and the Frog

The Scorpion and the Frog is an animal fable that seems to have first emerged in 1954. On account of its dark morality, there have been many references to it since then in popular culture, including in notable films, television shows, and books.

Synopsis

A scorpion asks a frog to carry it across a river. The frog hesitates, afraid of being stung, but the scorpion argues that if it did so, they would both drown. Considering this, the frog agrees, but midway across the river the scorpion does indeed sting the frog, dooming them both. When the frog asks the scorpion why, the scorpion replies that it was in its nature to do so.

Though the fable is recent, its outlook that certain natures cannot be reformed was common in ancient times, as in Aesop's fable of The Farmer and the Viper. Here the snake's reply indicates that what is fundamentally vicious will not change.[1]

Development

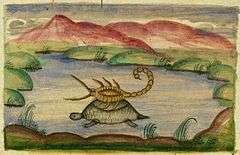

The origin of the fable is somewhat uncertain. An early appearance is in the 1944 book The Hunter of the Pamirs. A Novel of Adventure in Soviet Central Asia by Georgi Tushkan[2] A subsequent appearance of the fable is in the 1954 script of Orson Welles' film Mr. Arkadin.[3][4] Although there are similarities with the fable of The Frog and the Mouse, the story here has more in common with later variants in which a scorpion appears that emerged in Asia during the Middle Ages, notably a story about a tortoise and scorpion.

A study published in a German journal in 2011[5] can find no connection between that fable and the Indian tradition of the Panchatantra. Whereas the original Sanskrit work and its early translations do not contain any fable resembling The Scorpion and the Frog, a later fable, The Scorpion and the Turtle,[6] is to be found interpolated in post-Islamic variants of the Panchatantra.[7] In The Scorpion and the Turtle, the turtle drowns the scorpion after the scorpion tries but fails to sting the turtle through its hard shell. The study suggests that the interpolation occurred between the 12th and 13th centuries in the Persian language area[8] and may offer a new starting point for further research on the question of the fable's origin.

In a paper published in 1900[9], Kenneth McKenzie noted:

In the Anvar-i Suhaili a friendly tortoise carries a scorpion across a river ; the scorpion stings the tortoise, which reflects that to cherish a base friend is to sacrifice oneself. This tale was put in the place of an other that appears in the Panchatantra; and Benfey suggests that it may have been influenced by the Aesopic fable of the Frog and the Mouse.3 In Talmudic literature there are accounts of a scorpion crossing a river on the back of a frog in order to sting a man resting on the other side.4

Scorpion's nature

The fable relies to a significant extent on the idea of the creature's nature, which is of ancient reputation. Attesting to this, Oliver Goldsmith dedicated a chapter to "The Scorpion and its Varieties" in A History of the Earth and Animated Nature (1774) and observes that "It is certain that no animal in the creation seems endued with such an irascible nature...I have seen them attempt to sting a stick when put near them; and attack a mouse or a frog, when those animals were far from offering any injury."[10]

John Malcolm, in his 1827 Sketches of Persia, from the Journals of a Traveller in the East, relates another version of "The Scorpion and the Tortoise" nearer to the modern-day "Scorpion and the Frog" which also plays on the theme. In this version, after the scorpion begs to be taken over the water and then attempts to sting the tortoise midstream, it is brought safely onshore, after which the tortoise remonstrates:

- "Are you not the most wicked and ungrateful of reptiles? But for me you must either have given up your journey, or have been drowned in that stream, and what is my reward? If it had not been for the armour which God has given me, I should have been stung to death." "Blame me not," said the scorpion, in a supplicatory tone, "it is not my fault; it is that of my nature; it is a constitutional habit I have of stinging."[11]

Earlier scorpion stories

The image of a scorpion carried across a river by a frog occurs at an earlier period, in the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli), though with a different outcome and purpose. The scorpion crosses the river and stings a man, killing him. This is said to illustrate how God's will is fulfilled in seemingly impossible ways.[12] An Arab variant is found in a Sufi source that illustrates divine providence with the tale of a scorpion that crosses the Nile on a frog's back in order to save a sleeping drunkard from being bitten by a snake.[13] In neither of the above, however, is the frog injured.

References

- ↑ "The Prisoner's Dilemma". The Ethical Spectacle. 1 (9). September 1995.

- ↑ Georgi, Tushkan (1944). The Hunter of the Pamirs. A Novel of Adventure in Soviet Central Asia. Hutchinson & Co. p. 320.

- ↑ See Giancarlo Livraghi's 2007 footnote to his book The Power of Stupidity (2004). Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ The story as told in Welles' film on YouTube. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ (in German) Takeda, Arata (March 2011). "Blumenreiche Handelswege: Ost-westliche Streifzüge auf den Spuren der Fabel Der Skorpion und der Frosch" (PDF). Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte. 85 (1): 124–152. doi:10.1007/BF03374756.

- ↑ Ashliman, D. L. (13 July 1999). "The Scorpion and the Tortoise". pitt.edu. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ Takeda (2011), pp. 140-142.

- ↑ Takeda (2011), p. 142.

- ↑ "Dante's References to Aesop". Seventeenth Annual Report of The Dante Society. Cambridge, Mass.: Boston Ginn and Company (for the Dante Society). 1900. (Note: The report is dated May 17, 1898, but was published in 1900 after a delay noted in the volume introduction.)

- ↑ Oliver Goldsmith, A History of the Earth and Animated Nature, 1825, published T. Kinnersley, pp. 761-762.

- ↑ John Malcolm, Sketches of Persia, from the Journals of a Traveller in the East, London 1827, Chapter XIV, p. 3.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli), Women (Seder Nashim), Vows (Nedarim), Chapter IV, p. 41.

- ↑ René Khawam, Propos d’amour des mystiques musulmans, choisis, présentés and traduits de l'arabe, Paris, 1960; section 3, Le soufisme authentique.