Dramatic structure

Dramatic structure is the structure of a dramatic work such as a play or film. Many scholars have analyzed dramatic structure, beginning with Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BCE). This article looks at Aristotle's analysis of the Greek tragedy and on Gustav Freytag's analysis of ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama.

History

In his Poetics, the Greek philosopher Aristotle put forth the idea the play should imitate a single whole action. "A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end" (1450b27).[1] He split the play into two parts: complication and unravelling.

The Roman drama critic Horace advocated a 5-act structure in his Ars Poetica: "Neue minor neu sit quinto productior actu fabula" (lines 189–190) ("A play should not be shorter or longer than five acts").

The fourth-century Roman grammarian Aelius Donatus defined the play as a three part structure, the protasis, epitasis, and catastrophe).

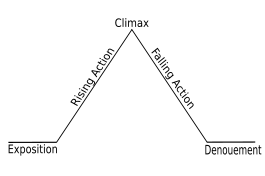

In 1863, around the time that playwrights like Henrik Ibsen were abandoning the 5-act structure and experimenting with 3 and 4-act plays, the German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas, a definitive study of the 5-act dramatic structure, in which he laid out what has come to be known as Freytag's pyramid.[2] Under Freytag's pyramid, the plot of a story consists of five parts: exposition (originally called introduction), rising action (rise), climax, falling action (return or fall), and dénouement/

Aristotle's analysis

Many structural principles still in use by modern storytellers were explained by Aristotle in his Poetics. In the part that we still have, he mostly analyzed the tragedy. A part analyzing the comedy is believed to have existed but is now lost.

Aristotle stated that the tragedy should imitate a whole action, which means that the events follow each other by probability or necessity, and that the causal chain has a beginning and an end.[5] There is a knot, a central problem that the protagonist must face. The play has two parts: complication and unravelling.[6] During complication, the protagonist finds trouble as the knot is revealed or tied; during unraveling, the knot is resolved.[7]

Two types of scenes are of special interest: the reversal, which throws the action in a new direction, and the recognition, meaning the protagonist has an important revelation.[8] Reversals should happen as a necessary and probable cause of what happened before, which implies that turning points needs to be properly set up.[9]

Complications should arise from a flaw in the protagonist. In the tragedy, this flaw will be his undoing.[10]

Freytag's analysis

According to Freytag, a drama is divided into five parts, or acts,[11] which some refer to as a dramatic arc: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement. Freytag's Pyramid can help writers organize their thoughts and ideas when describing the main problem of the drama, the rising action, the climax and the falling action.[12]

Although Freytag's analysis of dramatic structure is based on five-act plays, it can be applied (sometimes in a modified manner) to short stories and novels as well, making dramatic structure a literary element. Nonetheless, the pyramid is not always easy to use, especially in modern plays such as Alfred Uhry's Driving Miss Daisy and Arthur Miller's The Crucible, which is actually divided into 25 scenes without concrete acts.

Exposition

The exposition is the portion of a story that introduces important background information to the audience; for example, information about the setting, events occurring before the main plot, characters' back stories, etc. Exposition can be conveyed through dialogues, flashbacks, characters' thoughts, background details, in-universe media, or the narrator telling a back-story.[13]

Rising action

In the rising action, a series of events build toward the point of greatest interest. The rising action of a story is the series of events that begin immediately after the exposition (introduction) of the story and builds up to the climax. These events are generally the most important parts of the story since the entire plot depends on them to set up the climax and ultimately the satisfactory resolution of the story itself.[14]

Climax

The climax is the turning point, which changes the protagonist's fate. If the story is a comedy and things were going badly for the protagonist, the plot will begin to unfold in his or her favor, often requiring the protagonist to draw on hidden inner strengths. If the story is a tragedy, the opposite state of affairs will ensue, with things going from good to bad for the protagonist, often revealing the protagonist's hidden weaknesses.[15]

Falling action

During the falling action, the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels, with the protagonist winning or losing against the antagonist. The falling action may contain a moment of final suspense, in which the final outcome of the conflict is in doubt.[16]

Dénouement

The dénouement (UK: /deɪˈnuːmɒ̃,

The comedy ends with a dénouement (a conclusion), in which the protagonist is better off than at the story's outset. The tragedy ends with a catastrophe, in which the protagonist is worse off than at the beginning of the narrative. Exemplary of a comic dénouement is the final scene of Shakespeare’s comedy As You Like It, in which couples marry, an evildoer repents, two disguised characters are revealed for all to see, and a ruler is restored to power. In Shakespeare's tragedies, the dénouement is usually the death of one or more characters.

Criticism

Freytag's analysis was intended to apply to ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama, not modern.

Contemporary dramas increasingly use the fall to increase the relative height of the climax and dramatic impact (melodrama). The protagonist reaches up but falls and succumbs to doubts, fears, and limitations. The negative climax occurs when the protagonist has an epiphany and encounters the greatest fear possible or loses something important, giving the protagonist the courage to take on another obstacle. This confrontation becomes the classic climax.[19]

See also

- Jo-ha-kyū – dramatic arc in Japanese aesthetics

- Kishōtenketsu – a structural arrangement used in traditional Chinese and Japanese narratives

- Narrative transportation

- Scene and sequel

- Sonata form

- Three-act structure

Notes

- ↑ Perseus Digital Library (2006). Aristotle, Poetics

- ↑ University of South Carolina (2006). The Big Picture Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ University of Illinois: Department of English (2006). Freytag’s Triangle Archived July 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section VII

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XVIII

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XVIII

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section VI

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XI

- ↑ Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XIII

- ↑ Freytag, Gustav (1863). Die Technik des Dramas (in German). Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ↑ Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- ↑ Freytag (1900, pp. 115-121)

- ↑ Freytag (1900, pp. 125-128)

- ↑ Freytag (1900, pp. 128-130)

- ↑ Freytag (1900, pp. 133-135)

- ↑ "dénouement". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ↑ Freytag (1900, pp. 137-140)

- ↑ Teruaki Georges Sumioka: The Grammar of Entertainment Film 2005, ISBN 978-4-8459-0574-4; lectures at Johannes-Gutenberg-University in German

References

- Freytag, Gustav (1900) [Copyright 1894], Freytag's Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art by Dr. Gustav Freytag: An Authorized Translation From the Sixth German Edition by Elias J. MacEwan, M.A. (3rd ed.), Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, LCCN 13-283

External links

| Look up dénouement in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- English translation of Freytag's Die Technik des Dramas

- Another view on dramatic structure

- What’s Right With The Three Act Structure by Yves Lavandier, author of Writing Drama

- Other scholarly analyses

- Poetics, by Aristotle

- European Theories of the Drama, edited by Barrett H. Clark

- The New Art of Writing Plays, by Lope de Vega

- The Drama; Its Laws and Its Technique, by Elisabeth Woodbridge Morris

- The Technique of the Drama, by W.T. Price

- The Analysis of Play Construction and Dramatic Principle, by W.T. Price

- The Law of the Drama, by Ferdinand Brunetière

- Play-making: A Manual of Craftsmanship, by William Archer

- Dramatic Technique, by George Pierce Baker

- Theory and Technique of Playwriting, by John Howard Lawson

- Writing Drama by Yves Lavandier