The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

| The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by David Bowie | ||||

| Released | 16 June 1972 | |||

| Recorded | 8 November 1971 – 4 February 1972 | |||

| Studio | Trident Studios, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:29 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

| ||||

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (often shortened to Ziggy Stardust) is the fifth studio album by English musician David Bowie, released on 16 June 1972 in the United Kingdom. It was produced by Bowie and Ken Scott and features contributions from the Spiders from Mars, Bowie's backing band – Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey. The album was recorded in Trident Studios, London, like his previous album, Hunky Dory. Most of the album was recorded in November 1971 with further sessions in January and early February 1972.

Described as a loose concept album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is about Bowie's titular alter ego Ziggy Stardust, a fictional androgynous bisexual rock star who acts as a messenger for extraterrestrial beings. The character was retained for the subsequent Ziggy Stardust Tour through the United Kingdom, Japan and North America. The album, and the character of Ziggy Stardust, were influenced by glam rock and explored themes of sexual exploration and social taboos. A concert film of the same name, directed by D. A. Pennebaker, was recorded in 1973 and released a decade later.

Considered Bowie's breakthrough album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars peaked at number five on the UK Albums Chart and number 75 in the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart. As of January 2016 it had sold 7.5 million copies worldwide. The album received widespread critical acclaim and has been considered one of the greatest albums of all time. In 2017, it was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry, being deemed "culturally, historically, or artistically significant" by the Library of Congress.

Recording and production

Bowie started working on his fourth album, Hunky Dory on 8 June 1971 at Trident Studios, London.[1] RCA Records in New York heard the tapes and signed him to a three-album deal on 9 September. Hunky Dory was released on 17 December to positive reviews and moderate commercial success.[2] Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust were almost recorded back-to-back, but much of the material for Ziggy Stardust was recorded before Hunky Dory was released.[3] His backing band realised that most of the songs on Hunky Dory were not suitable live material, so they needed a follow-up that could be toured behind.[4]

Ziggy Stardust's sessions also took place at Trident, using a 16-track 3M M56 tape recorder.[5] The sessions started on 8 November 1971, with the bulk of the album recorded that month,[6] and concluded on 4 February 1972.[7] Bowie had recorded early versions of the songs "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself" in February 1971,[8] for the Arnold Corns side project, and had taped demos of "Ziggy Stardust" and "Lady Stardust" around that time.[9] The November 1971 sessions produced the final versions of those four songs, along with "Rock 'n' Roll Star" (later shortened to "Star"), "Soul Love", and "Five Years", as well as some unreleased tracks.[10][lower-alpha 1] In 2012, co-producer Ken Scott said that "95 percent of the vocals on the four albums I did with him as producer, they were first takes."[7]

Also recorded during the November sessions were five more songs: two covers, Chuck Berry's "Around and Around" (re-titled "Round and Round") and Jacques Brel's "Amsterdam" (re-titled "Port of Amsterdam"); and three original tracks: "Velvet Goldmine", and re-recordings of "Holy Holy" and "The Supermen". All these songs were initially slated for the album.[5][lower-alpha 1] Bowie also intended "All the Young Dudes",[12] "Rebel Rebel" and "Rock 'n' Roll with Me" to be on a Ziggy Stardust musical, which was later aborted.[13][14]

After recording some of the new songs for radio presenter Bob Harris's Sounds of the 70s as the newly dubbed Spiders from Mars in January 1972, the band returned to Trident that month to begin work on "Suffragette City" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide".[14] RCA executive Dennis Katz had complained that the album did not contain a single,[15] so Bowie wrote "Starman," which was completed on 4 February 1972. "Starman" was released as a single on 28 April 1972, and became a hit after a successful performance on the BBC television program Top of the Pops.[16][17] The Ron Davies cover "It Ain't Easy", recorded on 9 July 1971 during the Hunky Dory sessions, closed the first side of the album.[lower-alpha 1]

Concept and themes

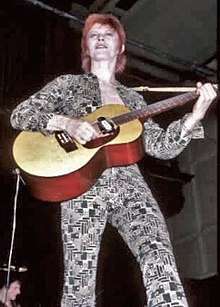

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars is about a bisexual alien rock superstar, called Ziggy Stardust.[18][19] Ziggy Stardust was not conceived as a concept album and much of the story was written after the album was recorded.[20][21] The characters were androgynous. Mick "Woody" Woodmansey, drummer for the Spiders from Mars, said the clothes they had worn had "femininity and sheer outrageousness", and that the characters' looks "definitely appealed to our rebellious artistic instincts".[22] Nenad Georgievski of All About Jazz said the record was presented with "high-heeled boots, multicolored dresses, extravagant makeup and outrageous sexuality".[23] Bowie had already developed an androgynous appearance, which was approved by critics, but received mixed reactions from audiences.[24] His love of acting led his total immersion in the characters he created for his music. After acting the same role over an extended period, it became impossible for him to separate Ziggy Stardust from his own offstage character. Bowie said that Ziggy "wouldn't leave me alone for years. That was when it all started to go sour ... My whole personality was affected. It became very dangerous. I really did have doubts about my sanity."[25] Fearing that Ziggy would define his career, Bowie quickly developed the persona of Aladdin Sane in his subsequent album. Unlike Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane was far less optimistic, instead engaging in aggressive sexual activities and heavy drugs.[26]

The character was inspired by British rock 'n' roll singer Vince Taylor, whom David Bowie met after Taylor had had a breakdown and believed himself to be a cross between a god and an alien.[27] However, Taylor was only part of the blueprint for the character.[28] Other influences included the cult musician Legendary Stardust Cowboy[29] and Kansai Yamamoto, who designed the costumes Bowie wore during the tour.[30] An alternative theory is that, during a tour, Bowie developed the concept of Ziggy as a melding of the persona of Iggy Pop with the music of Lou Reed, producing "the ultimate pop idol".[24][31] A girlfriend recalled his "scrawling notes on a cocktail napkin about a crazy rock star named Iggy or Ziggy", and on his return to England he declared his intention to create a character "who looks like he's landed from Mars".[24]

The Ziggy Stardust name came partly from the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, and partly because Ziggy was "one of the few Christian names I could find beginning with the letter 'Z'".[32] In 1990, Bowie explained that the "Ziggy" part came from a tailor's shop called Ziggy's that he passed on a train. He liked it because it had "that Iggy [Pop] connotation but it was a tailor's shop, and I thought, Well, this whole thing is gonna be about clothes, so it was my own little joke calling him Ziggy. So Ziggy Stardust was a real compilation of things."[33][34] He later asserted that Ziggy Stardust was born out of a desire to move away from the denim and hippies of the 1960's.[35] Along these lines, some critics assert that Bowie's artificial concoction of a rock star persona was a symbolic critique of the artificiality seen in the rock world of the time.[36]

The album's concept is loose, and pieced together after many of the songs were already recorded.[37] Indeed, before the album's initial release Bowie told a US interviewer:

What you have there on that album when it does finally come out, is a story which doesn’t really take place, it’s just a few little scenes from the life of a band called Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, who could feasibly be the last band on Earth—it could be within the last five years of Earth. I’m not at all sure. Because I wrote it in such a way that I just dropped the numbers into the album in any order that they cropped up. It depends in which state you listen to it in.[37]

With only five years left to survive, the earth is saved by the rock n' roll messiah, Ziggy Stardust. He wins the hearts of teens, scares parents, seduces everyone in his path, and eventually dies a victim of his own fame. According to Bowie, he "takes himself up to the incredible spiritual heights and is kept alive by his disciples". During the song "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide", the infinites arrive, and tear Ziggy Stardust to pieces on stage.[38] This wider interpretation of the Ziggy mythology is not explicitly stated anywhere in the album, but has been perpetuated over the years by fans and Bowie himself.

Music and lyrics

Ziggy Stardust has been retrospectively described as glam rock[39][40][41] and proto-punk.[42] Nenad Georgievski felt the record represents Bowie's interests in "theater, dance, pantomime, kabuki, cabaret and science fiction."[23]

For the album, Mick Ronson used an electric guitar plugged to a 100-watt Marshall amplifier and a wah-wah pedal;[7] Bowie played acoustic rhythm guitar.[41] The album begins with "Five Years", which opens with a minimalist drum figure. The track contains a repeated diatonic chord progression, resembling early 1950s rock and roll music.[43] "Five Years" sets up the central conflict of the album, the imminent destruction of earth.[44] The next track, "Soul Love", has a pop-jazz orchestration. In the song, Bowie's vocals are double tracked, which gives an effect of two people singing and suggests a band performance. Bowie also performs the alto saxophone on this song.[45] The following track, "Moonage Daydream", uses harmonic and melodic hooks, and heavy metal-style percussion and guitar.[45] "Moonage Daydream" introduces the alien messiah that will rescue the earth from disaster.[44] "Starman" was the last song written on the album and the first released as a single.[46] "Starman" replaced the cover of Chuck Berry's "Round and Round" when the band decided their album needed a single; it is perhaps the most concrete description of Ziggy's role in the rescue of earth.[46] "It Ain't Easy" is a raucous cover of Ron Davies.[47] Its arrangement was described by Ned Raggett as "a cabaret confection and a blasting rock apocalypse", characterized by quieter verses contrasting with choruses that contain overdubbed backing vocals and Ronson's "brilliantly triumphant guitar".[48] The track closes the first side of the album.

"Lady Stardust" has a moderate tempo, piano accompaniment and a pop hook.[47] The guitar and Bowie's and Ronson's arrangement on "Hang On to Yourself" resemble late 1970s punk rock.[47] "Suffragette City", one of the greatest hits of the album, is a "straight-ahead" track[49] which contains a saxophone-like section, produced with an ARP 2500 synthesiser.[5] The last track of the album, "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide," builds upon its minimalistic acoustic guitar textures as Ziggy's desperate message struggles to enlighten his earthling audience.[41][50] The arc of the album reaches its climax as the starman belts out his final words of wisdom before perishing onstage.[26]

Ziggy Stardust's concept and music were influenced by Bowie's earlier album, The Man Who Sold The World,[51] Iggy Pop, the lead singer of the proto-punk band the Stooges,[51] Lou Reed, vocalist and songwriter of the Velvet Underground,[51] Marc Bolan, lead singer of glam rock band T. Rex,[52][31] guitarist and singer Jimi Hendrix;[53] and progressive rock band King Crimson.[53] The album's lyrics discuss the artificiality of rock music in general, political issues, drug use, sexual orientation and stardom.[36][54] Stephen Thomas Erlewine described the album's lyrics as "fractured, paranoid" and "evocative of a decadent, decaying future".[52]

Artwork and packaging

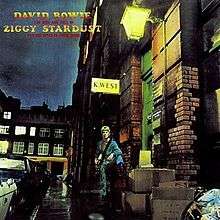

The album cover photograph was taken by Mick Rock[55] outside furriers "K. West" at 23 Heddon Street, London in January 1972,[56][57] looking south-east towards the centre of the city. Bowie said of the sign, "It's such a shame that sign went [was removed]. People read so much into it. They thought 'K. West' must be some sort of code for 'quest.' It took on all these sort of mystical overtones."[58] The post office in the background (now "The Living Room, W1" bar) was the site of London's first nightclub, The Cave of the Golden Calf, which opened in 1912. As part of street renovations, in April 1997 a red "K series" phonebox was returned to the street, replacing a modern blue phonebox, which in turn had replaced the original phonebox featured on the rear cover.[59]

Of the album's packaging in general, Bowie said:

The idea was to hit a look somewhere between the Malcolm McDowell thing with the one mascaraed eyelash and insects. It was the era of Wild Boys, by William S. Burroughs. [...] [It] was a cross between that and Clockwork Orange that really started to put together the shape and the look of what Ziggy and the Spiders were going to become. [...] Everything had to be infinitely symbolic."[58]

The cover was among the ten chosen by the Royal Mail for a set of "Classic Album Cover" postage stamps issued in January 2010.[60][61]

The rear cover of the original vinyl LP contained the instruction "TO BE PLAYED AT MAXIMUM VOLUME" (in caps). The instruction was omitted, however, from re-releases.[62]

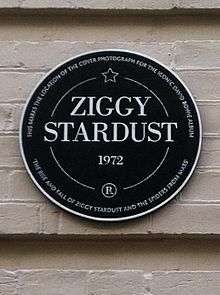

In March 2012, The Crown Estate, which owns Regent Street and Heddon Street, installed a commemorative brown plaque at No. 23 in the same place as the "K. West" sign on the cover photo. The unveiling was attended by original band members Woodmansey and Bolder, and was unveiled by Gary Kemp.[57] The plaque was the first to be installed by The Crown Estate and is one of the few plaques in the country devoted to fictional characters.[63]

Release and promotion

Widely considered to be Bowie's breakthrough album,[64][65][66] Ziggy Stardust was released on 16 June 1972 in the UK.[67][lower-alpha 2] An ambiguity surrounding Bowie's sexuality (even after Bowie declared himself as gay)[70][71] and a performance of "Starman" on Top of the Pops[16] brought public attention to the album.[72] Indeed, the Top of the Pops performance helped to solidify Bowie as a controversial pop icon.[26] In a 2010 interview in Rolling Stone, Bono said, "The first time I saw him was singing 'Starman' on television. It was like a creature falling from the sky. Americans put a man on the moon. We had our own British guy from space - with an Irish mother."[26]

Ziggy Stardust entered the top 10 in its second week on the UK Albums Chart. In its first week, the album sold 8,000 copies in Britain.[lower-alpha 1] After dropping down the chart in late 1972, the album began climbing the chart again; by the end of 1972, the album had sold 95,968 units in Britain.[lower-alpha 1] It peaked at number 5 on the chart in February 1973.[73] In the US, the album peaked at number 75 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart in April 1973.[74] It was eventually certified platinum and gold in the UK and US respectively.[75][76] The first single from the album, "Starman", charted at number 10 in the UK while peaking at 65 in the US.[77]

The album returned to the UK chart on 31 January 1981,[78] amid the New Romantic era that Bowie had helped inspire.[79] It was followed by a reissue of Aladdin Sane, which spent the first of 24 weeks on the chart in March 1982.[80] After Bowie's death from cancer on 10 January 2016, the album reached a new peak of 21 in the US Billboard 200.[81] It has sold an estimated 7.5 million copies worldwide, making it Bowie's second-best-selling album.[82][83]

Tour

In promotion of Ziggy Stardust, Bowie began the Ziggy Stardust Tour.[84] The first part of the tour started in the United Kingdom, and went from 29 January to 7 September 1972.[85] A show at the Toby Jug pub in Tolworth on 10 February of the same year was hugely popular, catapulting him to stardom and creating, as described by David Buckley, a "cult of Bowie".[86]

The tour lasted eighteen months, and passed through United States and Canada; it then continued to Japan, to promote his album Aladdin Sane (1973).[87] Bowie announced the end of the tour on 3 July 1973,[88] at the Hammersmith Apollo.[89] It had had more than 170 gigs.[90]

Notably, on 20 October 1972, Bowie performed a show in Santa Monica recorded for radio broadcast.[26] The bootleg recording of the performance circulated among fans, and came to represent the beginning of Bowie's long love affair with America.[26] It was officially issued in 2008 as Live Santa Monica '72.[91]

Reception and legacy

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Retrospective reviews | |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B+[94] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[70] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | |

| Uncut | |

Upon release, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars received highly favourable reviews by music critics. James Johnson of New Musical Express (NME) said the album has "a bit more pessimism" than on previous releases, and called the album's songs "fine".[100] Michael Watts of Melody Maker published that, while Ziggy Stardust had "no well-defined story line", it had "odd songs and references to the business of being a pop star that overall add up to a strong sense of biographical drama."[101] In Rolling Stone, writer Richard Cromelin gave the album a favourable review of "at least a 99" (assumed out of 100). But while Cromelin thought it was good, he felt that the record and its style might not be of lasting interest: "We should all say a brief prayer that his fortunes are not made to rise and fall with the fate of the 'drag-rock' syndrome".[102][103] Circus wrote that the album is "from start to finish [...] of dazzling intensity and mad design", and called it a "stunning work of genius".[104] The album was placed at the top of Creem's end of year list.[105]

Ziggy Stardust has been retrospectively acclaimed by critics, and recognised as one of the most important glam rock albums.[42][106][107] Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote for AllMusic: "Bowie succeeds not in spite of his pretensions but because of them, and Ziggy Stardust – familiar in structure, but alien in performance – is the first time his vision and execution met in such a grand, sweeping fashion."[52] Greg Kot, writing for Chicago Tribune, described the album as a "guitar-fueled song cycle", saying it "enacted the deaths of Joplin, Morrison, Hendrix and the '60s and presaged the dread, decadence and eroticism of a new era."[93]

In 1987, as part of their 20th anniversary, Rolling Stone magazine ranked it number 6 on "The 100 Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years".[108] In 1997, Ziggy Stardust was named the 20th greatest album of all time in a Music of the Millennium poll conducted in the UK.[109] It was named the 35th best album ever made by Rolling Stone. In 2004, it was placed at number 81 in Pitchfork's Top 100 Albums of the 1970s.[110] In 2006, Q magazine readers placed it at number 41,[111] In the same year, the album was chosen by Time magazine as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[112]

According to Acclaimed Music, a site which uses statistics to numerically represent reception among critics, Ziggy Stardust is the 16th most celebrated album of all time.[113] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[114] In 2013, Rolling Stone magazine ranked it 35th on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[115] In March 2017, the album was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the United States National Recording Preservation Board, which designates it as a sound recording that has had significant cultural, historical, or aesthetic impact in American life.[116]

Influence

The concept of Ziggy Stardust was revisited by Bowie himself in his later album Aladdin Sane (1973), which topped the UK chart, and was his first number-one album. Described by Bowie as "Ziggy goes to America", it contained songs he wrote while travelling to and across the US during the earlier part of the Ziggy tour.[14][87]

In 2004, Brazilian singer Seu Jorge contributed five cover versions of Bowie songs, three of them from Ziggy Stardust, to the soundtrack for the film The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.[117] Seu Jorge would later re-record the songs as a solo album called The Life Aquatic Studio Sessions. On the album's liner notes, Bowie wrote "Had Seu Jorge not recorded my songs in Portuguese I would never have heard this new level of beauty which he has imbued them with".[118] In 2016, Seu Jorge toured performing his Portuguese covers of Bowie's songs in front of sailboat-shaped screens.[119]

Musician Saul Williams named his 2007 album The Inevitable Rise and Liberation of NiggyTardust!, a play on the title of Bowie's album.[120]

The album was covered as part of rock band Phish's Halloween 'musical costume' on 31 October 2016.[121] In June 2017, an extinct species of wasp was named Archaeoteleia astropulvis after Ziggy Stardust ("astropulvis" is Latin for "stardust").[122][123]

Film

D. A. Pennebaker directed a documentary and concert film featuring Bowie and the Spiders from Mars performing in the final Ziggy Stardust Tour, at the Hammersmith Odeon, London on 3 July 1973.[124] At this show, Bowie made the sudden surprise announcement that the show would be "the last show that we'll ever do", later understood to mean that he was retiring his Ziggy Stardust persona.[125]

The full-length 90-minute film spent years in post-production[126] before finally having its theatrical premiere at the Edinburgh Film Festival, on 31 August 1979.[127] Prior to the premiere, the 35 mm film had been shown in 16 mm format a few times, mostly in United States college towns.[126] A shortened 60-minute version was broadcast once in the US on ABC-TV in October 1974.[124][128] In 1983, the film was released to theatres worldwide, corresponding with the release of its soundtrack album entitled Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture.[129] A digitally remastered 30th Anniversary Edition DVD, including additional material from the live show and extras, was released in 2003.[124][126][130]

Track listing

All tracks written by David Bowie, except where noted.

| Side one | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Five Years" | 4:42 |

| 2. | "Soul Love" | 3:34 |

| 3. | "Moonage Daydream" | 4:40 |

| 4. | "Starman" | 4:10 |

| 5. | "It Ain't Easy" (Ron Davies) | 2:58 |

| Total length: | 20:04 | |

| Side two | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 6. | "Lady Stardust" | 3:22 |

| 7. | "Star" | 2:47 |

| 8. | "Hang On to Yourself" | 2:40 |

| 9. | "Ziggy Stardust" | 3:13 |

| 10. | "Suffragette City" | 3:25 |

| 11. | "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" | 2:58 |

| Total length: | 18:25 | |

Reissues and re-releases

Ziggy Stardust was first released on CD in November 1984 by RCA.[131] The digital master recording was made from the equalised master tapes used for the LP release.[132]

1990 Rykodisc/EMI

Dr. Toby Mountain remastered Ziggy at Northeastern Digital Recording, Southborough, Massachusetts,[133] from the original master tapes for Rykodisc. The reissue was released on 6 June 1990, with five bonus tracks:[134]

- "John, I'm Only Dancing" (1972 single version, new 1990 remix) – 2:43

- "Velvet Goldmine" (Single B-side from the 1975 RCA re-release of "Space Oddity"; original recording from November 1971 album sessions) – 3:09

- "Sweet Head" (Previously unreleased outtake from November 1971 album sessions) – 4:14

- "Ziggy Stardust" (February 1971 demo) – 3:35

- "Lady Stardust" (March 1971 demo) – 3:35

1999 Virgin

The album was remastered by Peter Mew and released on 28 September 1999 by Virgin.[135]

2002 EMI/Virgin

On 16 July 2002, a 2-disc version was released by EMI/Virgin. The first in a series of 30th Anniversary 2CD Editions, this release included a newly remastered version as its first CD. The remaster on this edition reverses the left and right stereo channels on the first disc and many of the songs have been edited. Among other things, the three-note bridge between "Ziggy Stardust" and "Suffragette City", and the count-in to "Hang On to Yourself" are missing.[136]

The second disc contains twelve tracks, most of which had been previously released on CD as bonus tracks of the 1990–92 reissues. The new mix of "Moonage Daydream" was originally done for a 1998 Dunlop television commercial.[137] The bonus tracks:[131]

- "Moonage Daydream" (Arnold Corns version) – 3:53

- "Hang On to Yourself" (Arnold Corns version) – 2:54

- "Lady Stardust" (demo) – 3:33

- "Ziggy Stardust" (demo) – 3:38

- "John, I'm Only Dancing" – 2:49

- "Velvet Goldmine" – 3:13

- "Holy Holy" (1971 re-recording) – 2:25

- "Amsterdam" (Jacques Brel, Mort Shuman) – 3:24

- "The Supermen" (Alternate version, recorded for the Glastonbury Fayre in 1971, originally released on Glastonbury Fayre Revelations – A Musical Anthology, 1972[138] and on CD on 1990s Rykodisc/EMI Hunky Dory) – 2:43

- "Round and Round" (Chuck Berry) – 2:43

- "Sweet Head"(take 4) – 4:52

- "Moonage Daydream" (new mix) – 4:47

All tracks written by David Bowie, except as noted.[136]

2012 EMI/Virgin

On 4 June 2012, a "40th Anniversary Edition" was released by EMI/Virgin. This edition was remastered by original Trident Studios' engineer Ray Staff.[139]

The 2012 remaster was made available on CD and on a special, limited edition format of vinyl and DVD, featuring the new remaster on an LP, together with 2003 remixes of the album by Ken Scott (5.1 and stereo mixes) on DVD-Audio. The latter included bonus 2003 Ken Scott mixes of "Moonage Daydream" (instrumental), "The Supermen", "Velvet Goldmine" and "Sweet Head".[131][140][141]

2015–2017 Parlophone

On 25 September 2015 the 2012 remaster of the album and the 2003 remix (stereo mix) were both included in the Parlophone box set Five Years 1969–1973.[142][143] The album, in its 2012 remastering, was also rereleased separately, in 2015–2016, in CD, vinyl, and digital formats,[144] with Parlophone releasing the separate LP on 26 February 2016 on 180g vinyl.[145]

On 16 June 2017 Parlophone reissued the album as a limited edition LP pressed on gold vinyl.[146]

Personnel

Original album

Adapted from liner notes of Ziggy Stardust[147] and AllMusic.[148]

- David Bowie – vocals, acoustic guitar, saxophone, harpsichord, piano, arrangements

- Mick Ronson – electric guitar, backing vocals, keyboards, piano, string arrangements

- Trevor Bolder – bass, trumpet

- Mick Woodmansey – drums

- Uncredited personnel: Rick Wakeman – harpsichord (It Ain't Easy)[149] and Dana Gillespie – background vocals (It Ain't Easy)[150]

Technical

- David Bowie – production

- Ken Scott – production, audio engineering, mixing engineering

- Ray Staff – audio engineering[139]

1990 Rykodisc/EMI

- Dr. Toby Mountain – remastering engineering[133]

1999 Virgin release

Credits adapted from AllMusic.[135]

- Dana Gillespie – background vocals (track 5)

- Kevin Cann – design

- Peter Mew – remastering engineering

- Terry Pastor – artwork

- Paul Hicks – surround sound

- Rick Wakeman – harpsichord (track 5)

- Nigel Reeve – remastering engineering

Charts

Weekly charts

| Year | Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | UK Albums Chart[73] | 5 |

| 1973 | US Billboard 200[151] | 75 |

| 2016 | US Billboard 200[152] | 21 |

| US Top Catalog Albums (Billboard)[153] | 3 | |

| 2018 | Greek Albums Chart[154] | 32 |

Singles

| Year | Single | Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | "Starman" | UK Singles Chart | 10[73] |

| Billboard Pop Singles | 65[77] | ||

| 1974 | "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" | UK Singles Chart | 22[73] |

Sales and certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/Sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[155] | 2× Platinum | 1,500,000[156] |

| United States (RIAA)[157] | Gold | $1,000,000^ |

|

^shipments figures based on certification alone | ||

Footnotes

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dates and other informations of tracks:[11]

- "Five Years": "'It's Gonna Rain Again' enjoyed its brief moment in the studio on the very same day, 15 November 1971, that 'Five Years' was committed to tape."

- "It Ain't Easy": "[...] the Ron Davies cover 'It Ain't Easy' [...] [cut] on 9 July 1971 and originally slated for inclusion on Hunky Dory."

- "Lady Stardust": "'Lady Stardust' was one of the first Ziggy songs to be composed [...]. A stereo demo was recorded at Radio Luxembourg's studios on 9–10 March 1971.", "After an initial recording on 8 November 1971 was deemed unsuccessful, the definitive Ziggy Stardust version was cut three days later."

- "Moonage Daydream": "David recorded early versions of 'Moonage Daydream' and 'Hang on to Yourseld' at Radio Luxembourg's studios on 25 February.", "[...] the definitive Ziggy version, recorded at Trident on 12 November 1971."

- "Soul Love": "'Soul Love' was recorded at Trident on 12 November 1971."

- "Star": "After an initial recording on 8 November 1971 was deemed unsuccessful, the definitive Ziggy Stardust version was taped on 11 November under the working title 'Rock 'n' Roll Star'."

- "Sweet Head": "'Sweet Head' casts an intriguing light on the album's development. Completed on 11 November 1971, [...]"

- "Velvet Goldmine": "This [...] out-take was recorded at Trident on 11 November 1971."

- ↑ The US release date is unclear. The 27 May 1972 issue of Record World mentions that the album "is available"[68] and the album appeared in the Billboard Bubbling Under the Top LP's chart at number 207 the week ending 10 June 1972, suggesting a release date in late May.[69]

Citations

- ↑ Cann 2010, p. 219.

- ↑ Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 7–11

- ↑ Woodmansey 2017, p. 117.

- ↑ Woodmansey 2017, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 Owsinski, Bobby (11 January 2016). "The Making of David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust Album". Forbes. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Pegg 2016: "[...] [The] Ziggy Stardust sessions proper began at Trident on 8 November 1971, the main body of the album being recorded over the next fortnight."

- 1 2 3 Fanelli, Damian (23 April 2012). "On Its 40th Anniversary, 'Ziggy Stardust' Co-Producer Ken Scott Discusses Working with David Bowie". Guitar World. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Cann 2010, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Cann 2010, pp. 207, 255.

- ↑ Woodmansey 2017, pp. 88,114.

- ↑ Pegg 2016.

- ↑ Jones 2012, p. 67

- ↑ O'Leary 2015, p. 316

- 1 2 3 Pegg 2016

- ↑ Howard, Tom (11 January 2016). "Starman! – The Story of Bowie's Ziggy Stardust". NME. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- 1 2 "Bowie performs 'Starman' on 'Top of the Pops'". 7 Ages of Rock. BBC. 5 July 1972. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 125

- ↑ Auslander 2006, p. 120

- ↑ Thomas, Stephen (1 June 1974). "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Woodmansey 2017, p. 112

- ↑ O'Leary 2015: "Bowie wrote much of the Ziggy story after he made the album, having just sketched out a few plot points in a notebook".

- ↑ Woodmansey 2017, p. 123

- 1 2 Georgievski, Nenad (21 July 2012). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (40th Anniversary Remaster)". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Sandford 1997, pp. 73–74

- ↑ Sandford 1997, pp. 106–07

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sheffield, Rob. On Bowie (1st ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780062562708. OCLC 939703840.

- ↑ "BBC – BBC Radio 4 Programmes – Ziggy Stardust Came from Isleworth". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ Mahoney, Elisabeth (20 August 2010). "Ziggy Stardust Came from Isleworth – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 448

- ↑ Waldrep 2004, pp. 111–112

- 1 2 Pegg 2016: "Of the many individual influences on the character of Ziggy Stardust perhaps the most obvious is Iggy Pop [...] The same was equally true of Lou Reed, already a major influence on Bowie's songwriting. [...] But the Lou/Iggy axis was qualified by another vital influence: Marc Bolan."

- ↑ "11–14". The Observer. 20 June 2004. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Campbell 2005

- ↑ Bowie, David (25 August 2009). "David Bowie: the 1990 Interview". Paul Du Noyer (Interview). Interviewed by Paul Du Noyer. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011. In: "David Bowie". Q. No. 43. April 1990.

- ↑ "David Bowie On The Ziggy Stardust Years: 'We Were Creating The 21st Century In 1971'". NPR. 19 September 2003. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- 1 2 McLeod, Ken. "Space Oddities: Aliens, Futurism and Meaning in Popular Music". Popular Music. Vol. 22. JSTOR 3877579.

- 1 2 "David Bowie explains what 'Ziggy Stardust' is all about before it was released, 1972". Dangerous Minds. 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Burroughs & Lotringer 2001, p. 231

- ↑ Jarroush, Sami (8 July 2014). "Masterpiece Reviews: "David Bowie – The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars"". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Inglis 2013, p. 71

- 1 2 3 Perone 2007, p. 32

- 1 2 Blum, Jordan (12 July 2012). "David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Perone 2007, p. 27

- 1 2 Booth, Susan (2016). ""The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" — David Bowie (1972)" (PDF). The National Registry – via www.loc.gov.

- 1 2 Perone 2007, p. 28

- 1 2 "Single Stories: David Bowie, 'Starman'". Rhino. April 30, 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- 1 2 3 Perone 2007, p. 29

- ↑ "It Ain't Easy – David Bowie | Song Info | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Perone 2007, p. 30

- ↑ Perone 2007, p. 31

- 1 2 3 Ludwig, Jamie (13 January 2016). "David Bowie's Spirit of Transgression Made Him Metal Before Metal Existed". Noisey. Vice Media. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- 1 2 Woodmansey 2017, p. 114

- ↑ Perone 2007, p. 34

- ↑ Yeh, James (17 January 2016). "'Ziggy Stardust' Photographer Mick Rock Reflects on the Legacy of David Bowie". Vice. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Time Out (1998), Q (12–18 October 1984). "ZSC:Heddon St". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- 1 2 Press Association (27 March 2012). "David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust album marked with blue plaque". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- 1 2 Sinclair, David (1993). "Station to Station". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Michael Harvey. "The ZIGGY STARDUST Companion – Heddon Street, London at". 5years.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ↑ "Classic Album Covers: Issue Date – 7 January 2010". Royal Mail. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Michaels, Sean (8 January 2010). "Coldplay album gets stamp of approval from Royal Mail". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Freimark, Joel (11 January 2016). "The cultural earthquake caused by 'Ziggy Stardust'". Death and Taxes. Billboard Music. Billboard-Hollywood Reporter Media Group. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Site of Ziggy Stardust album cover shoot marked with plaque". BBC News. 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 52–56

- ↑ Bernard, Zuel (19 May 2012). "The rise and rise of Ziggy". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Perone 2007, p. 26

- ↑ "Happy 43rd Birthday to Ziggy Stardust". davidbowie.com. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ Ross, Ron (27 May 1972). "Bowie Tempts Teens: New Album, Single". "Who in the World" (PDF). Record World. p. 23. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "Billboard" (PDF). Billboard. 10 June 1972. p. 43. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- 1 2 Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Watts, Michael (22 January 2006). "David Bowie tells Melody Maker he's gay". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Inglis 2013, p. 73

- 1 2 3 4 "David Bowie". Official UK Charts Company. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (2001). Top Pop Albums 1955–2001. Menomonee Falls: Record Research Inc. p. 94. ISBN 0-89820-147-0.

- ↑ "RIAA Gold and Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ↑ "BPI Certified Awards". BPI. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- 1 2 Caulfield, Keith (1 November 2016). "David Bowie's Top 20 Biggest Billboard Hits". Billboard. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ "Official Albums Chart Top 75 – David Bowie". Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 318

- ↑ Roberts 1996, p. 71

- ↑ "David Bowie". Billboard. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ Dee, Johnny (7 January 2012). "David Bowie: Infomania". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Ziggy was a financial pioneer too". The Australian. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "David Bowie and the Rise of Ziggy Stardust". David Bowie and the Rise of Ziggy Stardust. BBC 4. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Pegg 2016: "The Ziggy Stardust Tour (UK) 29 January – 7 September 1972".

- ↑ Buckley 2005, pp. 135–36

- 1 2 Sandford 1997, pp. 108

- ↑ Goddard 2013, p. 295

- ↑ "Bowie Goes Back to Hammersmith". NME. 20 September 2002. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Buckley 2012, p. 164

- ↑ "David Bowie: Five Years 1969-1973 Album Review | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ↑ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Blender (47). May 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- 1 2 Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled on Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (1981). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the '70s. Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Larkin 2011

- ↑ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Q (128): 135–136. May 1997.

- ↑ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian. The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ↑ Dolan, Jon (July 2006). "How to Buy: David Bowie". Spin. 22 (7): 84. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Uncut (63): 98. August 2002.

- ↑ Johnson, James (3 June 1972). "Ziggy Stardust". New Musical Express. In: "David Bowie". The History of Rock 1972. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Watts, Michael (7 June 1972). "Ziggy Stardust". Melody Maker. In: "David Bowie". The History of Rock 1972. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Cromelin, Richard (20 July 1972). "The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Paytress, Mark (1998). Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars David Bowie. New York: Schirmer Books. pp. 117–120.

- ↑ "Ziggy Stardust". Circus. June 1972.

- ↑ "Albums of the Year". Creem. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "David Bowie on the Ziggy Stardust Years: 'We Were Creating The 21st Century In 1971'". NPR. 19 September 2003. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust & the Spiders From Mars (30th anniversary edition)". Billboard. 20 July 2002. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years". Rolling Stone. No. 507. August 1987.

- ↑ "The music of the millennium". BBC. 24 January 1998. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Picco, Judson. "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "Q Readers' Best Albums Ever 2006". Q. February 2006. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "The All-Time 100 Albums". Time. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ "David Bowie". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Dimery & Lydon 2010

- ↑ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: David Bowie, 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ "National Recording Registry Picks Are "Over the Rainbow"". Library of Congress. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Pegg 2016: "[...] and a plaintive Portuguese cover version was recorded by Seu Jorge for the 2004 film The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou."

- ↑ Cobo, Leila. "David Bowie Praised Seu Jorge for Taking His Songs to a 'New Level of Beauty' With Portuguese Covers: Listen". Billboard. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ "'The Life Aquatic' Actor Seu Jorge Plots David Bowie Covers Tour". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ↑ "Saul Williams Covers U2, Talks NiggyTardust". Stereogum. 5 November 2007. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ "Phish, Monday 10/31/2016". Phish.net. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Ferreira, Becky (23 June 2017). "This Freaky 100-Million-Year-Old Wasp Was Named for David Bowie". Vice. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "'Star dust' wasp is a new extinct species named after David Bowie's alter ego". Science Daily. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". phfilms.com. Pennebaker Hegedus Films. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ Jones 2012, pp. 162–164

- 1 2 3 Hall, Phil (22 August 2002). "Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Film Threat. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ Gibson, John (August 1979). "David Bowie Invited to Film Festival Premiere". Edinburgh Evening News.

- ↑ "Superstar David Bowie will perform...". The Sun Telegram. San Bernardino County, California. 20 October 1974. TV Week–16 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Theater Guide". New York. 30 January 1984. p. 63. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ "DVD Reviews: David Bowie: Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – The Motion Picture". Billboard. New York City: John Kilcullen. 5 April 2003. p. 39. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Griffin 2016

- ↑ "ZSC:RCA CD (1984)". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- 1 2 "Northeastern Digital home page". Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ↑ "The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars [Bonus Tracks]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 David Bowie. Ziggy Stardust: 30th Anniversary Edition (EMI, 2002).

- ↑ Drake, Rossiter (4 September 2002). "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars: 30th Anniversary Edition". Metro Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "EMI 30th Anniversary 2CD Limited Edition (2002)". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- 1 2 "Album Premiere: David Bowie's 'Ziggy Stardust' (Anniversary Remaster)". Rolling Stone. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "EMI to Release Ziggy Stardust 40th Anniversary Edition June 4". Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ "Remastered Ziggy 40th Vinyl/CD/DVD Due in June". davidbowie.com. 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Five Years 1969 – 1973 box set due September". davidbowie.com. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Paul Sinclair (6 August 2015). "David Bowie / Alternate Ziggy cover". Super Deluxe Edition. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Paul Sinclair (15 January 2016). "David Bowie / 'Five Years' vinyl available separately next month". Super Deluxe Edition. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016.

- ↑ "180g vinyl Bowie albums due February". davidbowie.com. 27 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust gold vinyl due". davidbowie.com. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-06-01.

- ↑ The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (Liner notes). David Bowie. RCA Records. 1972. LSP 4702. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – Credits". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Pegg 2016, p. 356

- ↑ O'Leary 2015, p. 190

- ↑ "allmusic (((Ziggy Stardust > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums". Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "Billboard 200 01/30/2016". Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "David Bowie Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ "IFPI Charts". www.ifpi.gr. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ "British album certifications – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust". British Phonographic Industry. Select albums in the Format field. Select Platinum in the Certification field. Type The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ↑ Lane, Daniel (9 March 2013). "David Bowie's Official Top 40 Biggest Selling Downloads revealed!". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ "American album certifications – David Bowie – Ziggy Stardust". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

Bibliography

- Auslander, Philip (2006). Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47-206868-5.

- Buckley, David (2005) [First published 1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Buckley, David (2012). Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story. Random House. ISBN 978-1-44-813247-8.

- Burroughs, William; Lotringer, Sylvère (2001). Burroughs live: the collected interviews of William S. Burroughs, 1960–1997. Semiotext(e). ISBN 1-58435-010-5.

- Campbell, Michael (2005). Popular music in America: the beat goes on. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-534-55534-9.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). David Bowie: An Illustrated Record. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-77966-8.

- Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- Goddard, Simon (2013). Ziggyology. Random House. ISBN 978-1-44-811846-5.

- Griffin, Roger (2016). David Bowie: The Golden Years. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85-712875-1.

- Inglis, Ian, ed. (2013). Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-40-949354-9.

- Jones, Dylan (2012). When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie, The Man Who Changed The World. Random House. ISBN 978-1-40-905213-5.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "David Bowie". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-85712-595-8.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie From '64 to '76. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78-099713-1.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie: New Edition: Expanded and Updated. Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78-565533-3.

- Perone, James (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27-599245-3.

- Roberts, David, ed. (1996). The Guinness Book of British Hit Albums. Guinness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-85112-619-7.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [First published 1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. Time Warner. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-33846-9.

- Waldrep, Shelton (2004). The aesthetics of self-invention: Oscar Wilde to David Bowie. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3418-1.

- Woodmansey, Woody (2017). Spider from Mars: My Life with Bowie. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-25-011762-5.

Further reading

- Weisbard, Eric; Craig Marks (1995). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.