The Ocean Cleanup

| |

| Formation | 2013 |

|---|---|

| Founded at | Delft, Netherlands |

| Type | Stichting |

| Purpose | Cleaning the oceans |

| Headquarters | Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Coordinates | 51°55′15″N 4°28′06″E / 51.92083°N 4.46833°ECoordinates: 51°55′15″N 4°28′06″E / 51.92083°N 4.46833°E |

| Boyan Slat | |

Staff | 70+[1] |

| Website |

www |

The Ocean Cleanup is a foundation that develops technologies to extract plastic pollution from the oceans and prevent more plastic debris from entering ocean waters. The organization was founded in 2013 by Boyan Slat, a Dutch-born inventor-entrepreneur of Croatian origin[2][3] who serves as its CEO. The foundation’s headquarters are in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Design

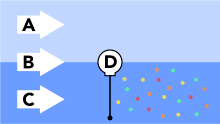

- A: Wind

- B: Waves

- C: Current

- D: Cross section of floating barrier.

- (Wind, waves, and current all act on the barrier, thus pushing it into the slower moving debris, which is moved only by the current.)

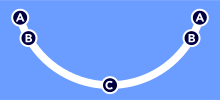

- A: Navigation pod

- B: Satellite pod

- C: Camera pod

The Ocean Cleanup proposes using passive floating structures localized in the ocean gyres, where marine debris tend to accumulate. These structures will create an artificial coastline, and utilize the ocean currents to concentrate the marine debris, so it can be collected. A solid screen underneath the floating pipe will catch the debris not directly on the surface. The entire system is to be powered without external energy.

Since the original proposal in October 2012, there have been multiple changes to the designs, among those whether the system is anchored or drifting, the method for collecting the debris, and the dimensions of the system.

Original proposal

In October 2012, that is, before The Ocean Cleanup was founded, Boyan Slat held a TED-talk, where he proposed such a system. This design, which was an early draft, consisted of long floating barriers fixed to the seabed, attached to a central platform shaped as a manta ray for stability. The barriers would direct the floating plastic to the central platform, which then would pick the plastic up from the water. Slat did not specify the dimensions of this system.[4]

In 2014, the design was revised, replacing the central platform with a tower not attached to the floating barriers. This platform would collect the plastic using a conveyor belt. The floating barriers were suggested to be 100 km wide. In 2015, this design won the London Design Museum Design of the Year.[5][6] and the INDEX: Award.[7][8]

Revised proposal

In May 2017, significant changes to the design were made:

- The dimensions were drastically reduced, from a total length of 100 km to a length of 1–2-kilometre (0.62–1.24 mi). The Ocean Cleanup suggested using a fleet of approximately 60 systems instead.[9]

- The seabed anchors were dropped and replaced with sea anchors, making the entire system drifting with the currents, but slower. This allows the plastic to "catch up" with the cleanup system. The lines to the anchor would keep the system in a U-shape. According to The Ocean Cleanup, this design allows the system to drift to the locations in the ocean with the highest concentration of debris.[10]

- An automatic system for collection of the plastic was dropped. Instead, the system should only concentrate the plastic, before it can be extracted by support vessels for transportation back to shore.[11]

In 2018, the sea anchors were dropped, because tests showed that the wind moved the system faster than the plastic. In this new design, the U-shape would have to turn forward, which would be achieved by having the underwater screen deeper in the middle of the system, creating more drag.[9]

Testing

Scale model tests

In the summer 2015, The Ocean Cleanup started performing scale model tests in controlled environments.[12] Tests took place in wave pools at Delares and MARIN. The purpose was to test the dynamics and load of the barrier, when exposed to currents and waves, and to gather data for continued computational modelling.[13]

The Ocean Cleanup performed more scale model tests in 2018.[14]

Open sea tests

A 100-metre segment went through a test in the North Sea, just off the coast of the Netherlands in the summer of 2016.[12][15] The purpose was to test the endurance of the materials chosen and the connections between elements. The test indicated that conventional oil containment booms were not fit for the harsh environments the system would face. They changed the floater material to a hard-walled HDPE pipe, which is flexible enough to follow the waves, and rigid enough to follow its open U-shape. More prototypes have been deployed to endurance test the system components since.[16]

On May 11, 2017, The Ocean Cleanup announced the next step is to test their new drifting system in the North Pacific in 2017.[10]

System 001

The first system was deployed on September 9, 2018 and The Ocean Cleanup estimates to be able to clean up 50% of the debris in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in five years’ time as of full-scale deployment in 2020.[9][10][11]

Research

Mega Expedition

Through a series of oceanic expeditions, The Ocean Cleanup researched the total mass and the distribution of plastic debris in the oceans, as well as technically and economically feasible ocean plastic recycling methods, technologies, and equipment. In August 2015, it conducted its so-called Mega Expedition, in which a fleet of approximately 30 vessels crossed the Great Pacific garbage patch using 652 surface nets to measure the concentration, spatial and size distribution of plastic there.[17] Researchers aboard mothership R/V Ocean Starr reported sighting of much more large-sized plastic debris in the Great Pacific Ocean gyre than expected.[18]

Aerial Expedition

In the fall of 2016, The Ocean Cleanup conducted a series of reconnaissance flights across the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This expedition was called the Aerial Expedition and was the first aerial survey of an ocean garbage patch. The objective of the expedition was to quantify the ocean’s biggest debris, i.e. discarded fishing gear called ghost nets. The data collected combined with the data from their previous Mega Expedition helped map the plastic pollution in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and results are expected to be published in 2017.

To quantify the debris, The Ocean Cleanup used a combination of human observers and sensors. They used a C-130 Hercules aircraft which flew at a low speed and low altitude for human researchers their CZMIL system (which uses LiDAR to create a 3D-image of the ghost nets) and the SASI hyperspectral SWIR imaging system (which uses an infrared camera to detect ocean plastic) to document ocean plastic pollution.[19] Boyan Slat said that the crew saw a lot more debris than expected.[20]

Scientific publications

On March 22, 2018, The Ocean Cleanup published the combined results from the Mega- and Aerial Expedition, detailing the size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch as well as the plastic concentration in it. They found that the patch is 1.6 million square kilometers large, with a concentration of up to 100 kg per square kilometer in the center of the patch, going down to 10 kg per square kilometer in the outer parts. They estimate the patch to contain 80 thousand metric tonnes of plastic, totalling 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, out of which 92% of the mass is still in pieces larger than 0.5 centimeter.[21][22][23]

In December 2017, a study about the persistent pollutants found in the plastic samples from the Mega Expedition was published in Environmental Science & Technology. The research team found there to be 180 times more plastic than naturally occurring biomass on the surface in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Furthermore, around 84% of the plastic samples had at least one PBT chemical with concentrations exceeding safe levels.[24][25]

The Ocean Cleanup research team published a paper in Nature Communications in June 2017, with a model of the river plastic input into the ocean. Their model showed that between 1.15 and 2.41 million metric tonnes of plastic enter the world's oceans every year, with 86% of the input stemming from rivers in Asia.[26][27]

In February 2015, the research team published a study in Biogeosciences, about vertical distribution of plastic, from samples made in the North Atlantic. They designed a new type of measurement tool, called a multi-level thrawl, which could measure concentration at 10 different depths simultaneously. The findings were that the plastic concentration decreases exponentially with depth, with the highest concentration being at the surface, with concentration approaching zero just a few meters down in the water column.[28][29]

Survey mobile application

In the second half of 2015, The Ocean Cleanup launched an iOS and Android application, the Visual Survey, which enables anyone on a boat on the ocean to contribute data. The purpose of this app is to provide scientists with the amount, kind and whereabouts of plastic pollution. The app times a 30-minute observation session during which observers log the debris they see. This replaces paper surveys, and the data will be shared with other scientists in addition to assisting The Ocean Cleanup in making decisions.

Funding

The Ocean Cleanup is mainly funded by donations and sponsors. It has received over $31.5 million in donations since foundation, from sponsors including Salesforce.com chief executive Marc Benioff, philanthropist Peter Thiel, Julius Baer Foundation and Royal DSM.[30] The Ocean Cleanup also raised over 2 million USD with the help of a crowdfunding campaign in 2014.[31]

Criticism

Several criticisms and doubts about method, feasibility, efficiency and return on investment have been raised in the scientific community about The Ocean Cleanup Array.

- The 5 Gyres Institute claim The Ocean Cleanup did not produce a thorough Environmental Impact Report and did not examine alternatives, for example having fishermen recover plastic pollution.[32] Boyan Slat states using conventional methods like vessels and nets would be inefficient in terms of time and costs.[33] The Ocean Cleanup is working on environmental impact studies with external experts to assess and minimize any environmental impact their technology may have.[34]

- Marcus Eriksen et al. (2014) have found 92% of plastic in the ocean is smaller than microplastics and cannot be caught by The Ocean Cleanup's system. Researchers have now found microplastic and synthetic fibers frozen into ice cores, abundant on the sea floor, and on every beach worldwide. Along the way, it passes through the bodies of billions of organisms.[35] However, the 2014 study shows the plastic mass is mainly found in the two larger size classes (86%).[36] Catching the larger debris before it breaks down into microplastics is The Ocean Cleanup's goal.[37]

- The 5 Gyres Institute argue that reducing plastic influx would capture more plastic before it degrades and impacts marine life, and likely cost less than the Array. Boyan Slat agreed that stopping the influx is necessary,[32] but argued that it is complementary to clean-up. By cleaning up what is left in the gyres, The Ocean Cleanup can prevent larger pieces from breaking down into the more harmful microplastics.[37]

- Mark Noak claims discouraging plastics consumption would be more effective long-term, and The Ocean Cleanup's strategy will instead enable environmentally harmful consumption patterns.[38] Boyan Slat argues a cleanup project has the potential to make the problem visible, and helps people become aware of the problem in general. It might also lead to spin-off technologies.[37]

Awards and recognition

The Ocean Cleanup and its CEO/founder Boyan Slat have won numerous distinctions. The United Nations Environment Programme awarded Slat with the Champion of the Earth in 2014,[39] and he was previously recognized as one of the 20 Most Promising Young Entrepreneurs Worldwide by Intel EYE50.[40] In 2015, Harald V of Norway awarded Slat the maritime industry's Young Entrepreneur Award and The Ocean Cleanup Array was named as a London Design Museum Design of the Year.[5][6] Also in 2015, the Ocean Cleanup Array won the INDEX: Award in 2015[7][8] and the 2015 Fast Company Innovation By Design Award in the category Social Good.[41] Foreign Policy recognized Slat as one of the 100 Global Thinkers of 2015.[42] In 2016, The Ocean Cleanup won the Katerva award also known as the ”Nobel Prize for Sustainability.”[43] The Ocean Cleanup was awarded the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association's Thor Heyerdahl award in May 2017.[44]

References

- ↑ About The Ocean Cleanup, Theoceancleanup.com. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ "HRVAT KOJI ČISTI OCEANE Moj tata živi u Istri, a ja sam s ušteđevinom od 200 € ostvario san". jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ "Nizozemac hrvatskog podrijetla izumio sustav koji elimira plastični otpad iz mora". www.monitor.hr. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ TEDx Talks (2012-10-24), How the oceans can clean themselves: Boyan Slat at TEDxDelft, retrieved 2018-09-09

- 1 2 Winners announced for three Nor-Shipping 2015 Awards Archived 2015-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. Mynewsdesk.com. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- 1 2 Designs of the Year 2015, Designmuseum.org. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- 1 2 Post (2015-08-27). "Ocean cleaner wins top Danish design award". GlobalPost.com. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- 1 2 "THE OCEAN CLEANUP ARRAY – INDEX: AWARD 2015 WINNER (COMMUNITY CATEGORY) - INDEX: Design to Improve Life®". INDEX: Design to Improve Life®. 2015-08-27. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- 1 2 3 www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Technology". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- 1 2 3 www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Pacific cleanup set to start in 2018". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- 1 2 www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Start Pacific Cleanup". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- 1 2 "Can this project clean up millions of tons of ocean plastic?". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Scale Model Testing". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Looking Back on our Most Advanced Scale Model Test to Date". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "First Cleanup Barrier Test to be deployed in Dutch waters". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Unscheduled Learning Opportunities on the North Sea". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ↑ Mega Expedition, Theoceancleanup.com. Vittu mitä paskaa.

- ↑ Garbage ‘patch’ is much worse than believed, entrepreneur says, SFgate.com. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Aerial Expedition". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ Milman, Oliver (2016-10-04). "'Great Pacific garbage patch' far bigger than imagined, aerial survey shows". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "The Exponential Increase of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ↑ Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A. (2018-03-22). "Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch - The Ocean Cleanup". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "How Ocean Plastics Turn into a Dangerous Meal". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ Chen, Qiqing; Reisser, Julia; Cunsolo, Serena; Kwadijk, Christiaan; Kotterman, Michiel; Proietti, Maira; Slat, Boyan; Ferrari, Francesco F.; Schwarz, Anna (2017-12-21). "Pollutants in Plastics within the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre". Environmental Science & Technology. 52 (2): 446–456. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b04682. ISSN 0013-936X.

- ↑ Lebreton, Laurent C. M.; van der Zwet, Joost; Damsteeg, Jan-Willem; Slat, Boyan; Andrady, Anthony; Reisser, Julia (2017-06-07). "River plastic emissions to the world's oceans". Nature Communications. 8: 15611. doi:10.1038/ncomms15611. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Plastic Sources". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Vertical Distribution Expeditions". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ Reisser, J.; Slat, B.; Noble, K.; du Plessis, K.; Epp, M.; Proietti, M.; de Sonneville, J.; Becker, T.; Pattiaratchi, C. (2015-02-26). "The vertical distribution of buoyant plastics at sea: an observational study in the North Atlantic Gyre". Biogeosciences. 12 (4): 1249–1256. doi:10.5194/bg-12-1249-2015. ISSN 1726-4189.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "The Ocean Cleanup Raises 21.7 Million USD in Donations to Start Pacific Cleanup Trials". The Ocean Cleanup. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Crowd Funding Campaign". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- 1 2 "Why the Ocean Clean Up Project Won't Save Our Seas - Planet Experts". Planet Experts. 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "How it all began". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "FAQ". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ Cózar, Andrés; Echevarría, Fidel; González-Gordillo, J. Ignacio; Irigoien, Xabier; Úbeda, Bárbara; Hernández-León, Santiago; Palma, Álvaro T.; Navarro, Sandra; García-de-Lomas, Juan (2014-07-15). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (28): 10239–10244. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- ↑ Eriksen, Marcus; Lebreton, Laurent C. M.; Carson, Henry S.; Thiel, Martin; Moore, Charles J.; Borerro, Jose C.; Galgani, Francois; Ryan, Peter G.; Reisser, Julia (2014-12-10). "Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e111913. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111913. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4262196. PMID 25494041.

- 1 2 3 www.theoceancleanup.com, The Ocean Cleanup,. "Why We Need To Clean The Ocean's Garbage Patches". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ Mark Noack, "Ocean Cleanup targets garbage vortex", Mountain View Voice, 2016-10-07, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Boyan Slat Founder – The Ocean Cleanup 2014 Champion of the Earth INSPIRATION AND ACTION Archived 2015-11-18 at the Wayback Machine., web.unep.org. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ C2-MTL AND INTEL REVEAL TOP 20 FINALISTS, C2Montreal.com. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ The 2015 Innovation By Design Awards Winners: Social Good Fastcodesign.com retrieved 2015-11-17

- ↑ "The Leading Global Thinkers of 2015". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ "Plastic-scooping Ocean Cleanup project wins prestigious Katerva Award". Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ "Press release: Winner of the Heyerdahl Award 2017 - Nor-Shipping". Nor-Shipping. 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Ocean Cleanup. |