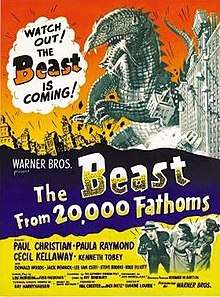

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms

| The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Eugène Lourié |

| Produced by |

Jack Dietz Hal E. Chester |

| Screenplay by |

Fred Freiberger Eugène Lourié Louis Morheim Robert Smith |

| Based on | The Fog Horn (short story) by Ray Bradbury |

| Starring |

Paul Christian Paula Raymond Cecil Kellaway Kenneth Tobey |

| Music by | David Buttolph |

| Cinematography | Jack Russell |

| Edited by | Bernard W. Burton |

Production company |

Jack Dietz Productions |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $200,000 |

| Box office | $2.25 million |

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is a 1953 American black-and-white science fiction monster film from Warner Bros., produced by Jack Dietz and Hal E. Chester, directed by Eugène Lourié, that stars Paul Christian, Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway, and Kenneth Tobey.[1] The film's stop-motion animation special effects are by Ray Harryhausen. Its screenplay is based on Ray Bradbury's short story The Fog Horn, specifically the scene where a lighthouse is destroyed by the title character.[2]

The storyline concerns a fictional dinosaur, the Rhedosaurus, which is released from its frozen, hibernating state by an atomic bomb test in the Arctic Circle.[2] The beast begins to wreak a path of destruction as it travels southward, eventually arriving at its ancient spawning grounds, which includes New York City.[3]

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was one of the first atomic monster movies which helped inspire a generation of creature features.[4][5]

Plot

Far north of the Arctic Circle, a nuclear bomb test, dubbed "Operation Experiment", is conducted. Prophetically, right after the blast, physicist Thomas Nesbitt muses, "What the cumulative effects of all these atomic explosions and tests will be, only time will tell". The explosion awakens a 200-foot (61 m) long carnivorous animal known as Rhedosaurus,[6] thawing it out of the ice where, it had been held in suspended animation. Nesbitt is the only surviving witness to the beast's awakening, and is later dismissed out-of-hand as being delirious at the time of his "sighting". Despite the skepticism, he persists, knowing what he saw.

The Beast begins making its way down the east coast of North America, sinking a fishing ketch off the Grand Banks, destroying another near Marquette, Canada, wrecking a lighthouse in Maine, and destroying buildings in Massachusetts. Nesbitt eventually gains allies in paleontologist Thurgood Elson and his young assistant Lee Hunter after one of the surviving fishermen identifies from a collection of drawings the very same dinosaur as Nesbitt saw. Plotting the sightings of the Beast's appearances on a map for skeptical military officers, Elson proposes the Beast is returning to the Hudson River area, where fossils of Rhedosaurus were first found. In a diving bell search of the undersea Hudson River Canyon, Professor Elson is killed after his bell is swallowed by the Beast, which eventually comes ashore in Manhattan. A later newspaper report of its rampage lists "180 known dead, 1500 injured, damage estimates $300 million".

Meanwhile, military troops led by Colonel Jack Evans attempt to stop the Rhedosaurus with an electrified barricade, then blast a hole with a bazooka in the Beast's throat, which drives it back into the sea. Unfortunately, it bleeds all over the streets of New York, unleashing a "horrible, virulent" prehistoric contagion, which begins to infect the populace, causing even more fatalities. The infection precludes blowing up the Rhedosaurus or even setting it ablaze, lest the contagion spread further. It is then decided to shoot a radioactive isotope into the Beast's neck wound with hopes of burning it from the inside, killing it without releasing the contagion.

When the Rhedosaurus comes ashore and reaches Coney Island's amusement park, military sharpshooter Corporal Stone takes a rifle grenade loaded with a potent radioactive isotope, and climbs on board a roller coaster. Riding the coaster to the top of the tracks, so he can get to eye-level with the Beast, he fires the isotope into its open neck wound. The creature thrashes about in reaction, causing the roller coaster to spark when falling to the ground, setting the amusement park ablaze. With the fire spreading rapidly, the park becomes completely engulfed in flames. The Rhedosaurus eventually dies from isotope poisoning and heat stroke.

Cast

- Paul Christian as Professor Tom Nesbitt

- Paula Raymond as Lee Hunter

- Cecil Kellaway as Dr. Thurgood Elson

- Kenneth Tobey as Colonel Jack Evans

- Donald Woods as Captain Phil Jackson

- Ross Elliott as George Ritchie

- Steve Brodie as Sgt. Loomis

- Jack Pennick as Jacob Bowman

- Michael Fox as ER doctor

- Lee Van Cleef as Corporal Jason Stone

- Frank Ferguson as Dr. Morton

- King Donovan as Dr. Ingersoll

- James Best as Charlie, radar operator

Production

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms had a production budget of $200,000.[7] It earned $2.25 million at the North American box office during its first year of release[8] and ended up grossing more than $5 million.[9][10] Original prints of Beast were sepia toned.[11]

The film was announced in the trades as The Monster from Beneath the Sea. During preproduction, it was brought to Dietz and Chester's attention by Ray Harryhausen that Ray Bradbury had written a short story called The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms that was just published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1951 (it was later anthologized under the title "The Fog Horn").[12] This story was about a marine based prehistoric dinosaur that destroys a lighthouse. A similar sequence appeared in the draft of the script for The Monster from Beneath the Sea. The producers, who wished to share Bradbury's reputation and popularity, promptly bought the rights to his story and changed the film's title to match the title of the story. Bradbury's name was used extensively in the promotional campaign and a credit that read "Suggested by the Saturday Evening Post Story by Ray Bradbury" was added to the credits.[13]

The original music score was composed by Michel Michelet, but when Warner Bros. purchased the film they had a new score written by David Buttolph. Ray Harryhausen had been hoping that his film music hero Max Steiner would be able to write the music, as Steiner had written the landmark score for King Kong, and Steiner was under contract with Warner Bros. at the time. Unfortunately for Harryhausen, Steiner had too many commitments to allow him to score the film, but fortunately for film music fans, Buttolph composed one of his most memorable and powerful scores, setting much of the tone for giant monster music of the 1950s.[14]

Some early pre-production conceptual sketches of the Beast showed that at one point it was to have a shelled head and at another point was to have a beak.[15] Creature effects were assigned to Ray Harryhausen, who had been working with Willis O'Brien, the man who created King Kong, for years. The monster of the film looks nothing like the Brontosaurus-type creature of the short story. The creature in the film is instead some kind of Tyrannosaurus rex-type prehistoric predator (though it was quadrupedal, unlike any real carnivorous dinosaur, and more closely resembled a rauisuchian). A drawing of the creature was published along with the story in The Saturday Evening Post.[16] At one point, there were plans to have the Beast snort flames, but this idea was dropped before production began due to budget restrictions. However, the concept was still used for the film poster artwork. Later, the Beast's nuclear flame breath would be the inspiration for the original Japanese film Gojira (1954, Godzilla).[17]

In a scene attempting to identify the Rhedosaurus, Professor Tom Nesbitt rifles through dinosaur drawings by Charles R. Knight, a man whom Harryhausen claims as an inspiration.[18]

The dinosaur skeleton in the museum sequence is artificial; it was obtained from storage at RKO Pictures where it had been constructed for their classic comedy Bringing Up Baby (1938).[19]

The climactic roller coaster live action scenes were filmed on location at The Pike in Long Beach, California and featured the Cyclone Racer entrance ramp, ticket booth, loading platform, and views of the structure from the beach. Split-matte, in-camera special effects by Harryhausen effectively combined the live action of the actors and the roller coaster background footage from The Pike parking lot with the stop-motion animation of the Beast destroying a shooting miniature of the coaster.[20]

Reception

In his review of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms for The New York Times, Armond White was not impressed with the story: "And though the sight of the gigantic monster rampaging through such areas as Wall Street and Coney Island sends the comparatively ant-like humans on the screen scurrying away in an understandable tizzy, none of the customers in the theatre seemed to be making for the hills. On sober second thought, however, this might have been sensible".[21]

The Variety review focused more on the impressive special effects: "Producers have created a prehistoric monster that makes Kong seem like a chimpanzee. It's a gigantic amphibious beast that towers above some of New York's highest buildings. The sight of the beast stalking through Gotham's downtown streets is awesome. Special credit should go to Ray Harryhausen for the socko technical effects".[22] Our Culture Mag critic Christopher Stewardson rated the film 3.5 out of 5.[23]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively collected 18 reviews and gave the film a 94% approval rating.[24]

Legacy

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was the first live-action film to feature a giant monster awakened/brought about by an atomic bomb detonation,[25] preceding Godzilla by 16 months. The film's financial success helped spawn the genre of giant monster films of the 1950s. Producers Jack Dietz and Hal E. Chester got the idea to combine the growing paranoia about nuclear weapons with the concept of a giant monster after a successful theatrical re-release of King Kong.[16] In turn, this craze included Them! the following year about giant ants, the Godzilla series from Japan that has spawned films from 1954 into the present day,[4][5] and two British features helmed by Beast director Eugène Lourié, Behemoth, the Sea Monster (UK 1959, US release retitled The Giant Behemoth), and Gorgo (UK 1961).[26]

The film Cloverfield (2008), which also involves a giant monster terrorizing New York City, inserts a frame from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (along with frames from King Kong and Them!) into the hand-held camera footage used throughout the film.[27]

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was nominated for AFI's Top 10 Science Fiction Films list.[28]

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms also appears in Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990).

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) - Eugène Lourié - Cast and Crew - AllMovie". AllMovie.

- 1 2 "The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) - Notes - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ "The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- 1 2 Jones 1995, p. 42.

- 1 2 Hood, Robert. "A Potted History of Godzilla." roberthood.net. Retrieved: January 30, 2015.

- ↑ The Dinosaur Films of Ray Harryhausen: Features, Early 16mm Experiments and Unrealized Projects by Roy P. Webber

- ↑ Van Hise 1993, p. 102.

- ↑ "The Top Box Office Hits of 1953." Variety, January 13, 1954.

- ↑ Johnson 1995, p. 61.

- ↑ "Hal E. Chester". The Times. London. May 2, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2018. (subscription required)

- ↑ Harryhausen & Dalton 2003, p. 58

- ↑ Ray Bradbury, The Golden Apples of the Sun, Doubleday, March 1953.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F. (1982) The Dinosaur Scrapbook, Citadel Press

- ↑ "David Buttolph - Biography, Movie Highlights and Photos - AllMovie". AllMovie.

- ↑ "Concept art from 'The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms'." theseventhvoyage.com. Retrieved: January 30, 2015.

- 1 2 Rovin 1989

- ↑ McKenna, A. T. (September 16, 2016). "Showman of the Screen: Joseph E. Levine and His Revolutions in Film Promotion". University Press of Kentucky – via Google Books.

- ↑ Harryhausen, Ray (2010) Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life, Aurum Press Ltd

- ↑ Berry, Mark F. (January 1, 2005). "The Dinosaur Filmography". McFarland – via Google Books.

- ↑ Hankin, Mike (2008) Ray Harryhausen-Master of the Majiks, Archive Editions LLC

- ↑ White, Armond (A.W.). "Movie review: The Beast From 20 000 Fathoms (1953; 'Beast From 20,000 Fathoms' invades city." The New York Times, June 25, 1953.

- ↑ "Review: ‘The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms’." Variety. Retrieved: January 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Review: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953)" Our Culture Mag. Retrieved: May 04, 2017.

- ↑ "The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953)". Rotten Tomatoes (Fandango Media). Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Poole 2011, p. 124.

- ↑ Berry, Mark F. The Dinosaur Filmography, McFarland & Company

- ↑ "Easter egg monster images." Cloverfield News. Retrieved: January 30, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot." AFI. Retrieved: January 30, 2015.

Bibliography

- Harryhausen, Ray; Dalton, Tony (2003). Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life. United States: Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0823084029.

- Johnson, John J.J. (1995). Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0093-5.

- Jones, Stephen (1995). The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-487-7.

- Poole, W. Scott. (2011). Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-60258-314-6.

- Rovin, Jeff (1989). The Encyclopedia of Monsters. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-1824-3.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, 21st Century Edition. 2009. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company,(First Edition 1982). ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Van Hise, James (1993). Hot Blooded Dinosaur Movies. Las Vegas: Pioneer Books. ISBN 1-55698-365-4.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms |