Teresita Fernández

| Teresita Fernández | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

May 12, 1968 Miami, Florida U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Southwest Miami High School |

| Alma mater |

Florida International University Virginia Commonwealth University |

| Known for | U.S. Commission of Fine Arts |

Teresita Fernández (born May 12, 1968) is a visual artist best known for her prominent public sculptures and unconventional use of materials. Fernández's work is characterized by an interest in perception and the psychology of looking. Her experiential, large-scale works are often inspired by landscape and natural phenomena as well as diverse historical and cultural references.[1] The artist's work has explored issues in contemporary art related to perception and the fabrication of the natural world. Often her sculptures present spectacular optical illusions and evoke natural phenomena, land formations, and water in its infinite forms.[2]

Early life and education

Fernández was born in Miami, Florida, to Cuban parents in exile. Her family fled Fidel Castro's regime in July 1959, six months after the Cuban Revolution. As a child, she spent much of her time making things in the atelier of her great aunts and grandmother, all whom had been trained as highly skilled couture seamstresses in Havana, Cuba.[3]

In 1986, Fernández graduated from Southwest Miami High School. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Florida International University in 1990, and a Masters of Fine Art from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1992.

Career

In 1996, Fernández had her first solo exhibition in New York at Deitch Projects, where she transformed the gallery into an empty, indoor swimming pool that was in part inspired by a house designed for Josephine Baker in 1920's Paris. The following year she was included in an exhibition at New Museum and in a group show titled "The Crystal Stopper" at Lehmann Maupin curated by Carlos Basualdo. Her first solo museum show was at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia in 1999. Soon after that she had solo exhibitions at Site Santa Fe, Castello di Rivoli, and The Centro de Arte Contemporaneo, in Málaga, Spain.

In 2000, Fernández's site-specific project titled "Hothouse" was installed at The Museum of Modern Art. The work was commissioned as part of "Open Ends," the third and final cycle of "MoMA2000," on view September 28, 2000 through January 2, 2001. The installation, a sprawling vine-like pattern (white on the front and green on the back), meandered across the glass looking out to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden.

The Public Art Fund commissioned Fernández's "Bamboo Cinema" (2001) in New York's Madison Square Park. The sculpture, a maze-like form made of concentric circles that functioned like an early cinematic device, was made of translucent elements that optically shifted the surroundings like an animated filmstrip. The vertical elements of the sculpture were made of extruded polycarbonate tubes of different diameters that had a green-hued stripe pattern embedded into them. The transparent tubes allowed different degrees of visibility from every angle. As in the earliest examples of cinematic devices, the vertical lines acted as a continuous shutter, constantly interrupting any movement so that it appeared to flicker.

In 2005, she created a piece called "Fire" during her residency at The Fabric Workshop and Museum that was constructed using thousands of silk threads from Franco Scalamandré. The dyed silk threads were held taut between two rings and suspended from the ceiling, creating a unique optical illusion of transparency and dense color that appeared to vibrate when experienced by the moving viewer.

In 2006, at the age thirty-five, she became the youngest artist commissioned by the Seattle Art Museum for the museum's Olympic Sculpture Park. Her permanently installed work, "Seattle Cloud Cover" (2006), allows visitors to walk under a block-long covered skyway while viewing the city's skyline appearing through tiny holes in color-saturated glass.

Fernández has made many sculptures out of raw, mined graphite as a way of looking at the intersection between drawing, land art and landscape painting. Her sculpture "Borrowdale (Drawn Waters)" (2009) is a reference to Cumbria, England, the location where graphite was first discovered and mined in the 1500s.

You can rephrase blindness in terms of the varieties of not-seeing:shadows, darkness, inaccessibility, denial, cloaking, peeking, squinting, hiding, camouflaging. These, too, are degrees of blindness, though less specific to the physicality of the eye and more inextricably linked to thinking, dreaming, and imagining. In my new "Nocturnal" series, I am in fact trying to amplify seeing by dimming it.[4]

Fernández's "Blind Blue Landscape" (2009) at the renowned Bennesee Art Site in Naoshima, Kagawa consists of over thirty thousand hand-made mirrored glass cubes installed on a curved wall in the Tadao Ando designed building. Each mirror becomes like a miniature portrait reflecting the dramatic landscape of the Seto Inland Sea outside.

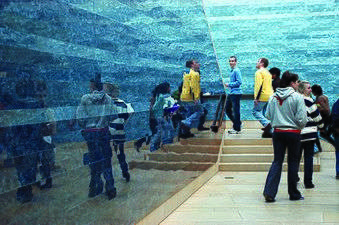

In 2009, the Blanton Museum of Art, commissioned the large permanent work titled "Stacked Waters" that occupies the museum's Rapoport Atrium. "Stacked Waters" consists of 3,100 square feet of custom-cast acrylic that covers the walls in a striped pattern. The work's title alludes to artist Donald Judd's "stack" sculptures—series of identical boxes installed vertically along wall surfaces—as well as to his sculptural explorations of box interiors. Fernández noticed how The Blanton's atrium functions like a box, and given its architectural nods to the arches of Roman baths and cisterns, she sought to fill its spatial volume with an illusion of water.[5][6]

Also in 2009, Fernández had a piece called "Starfield" made up of mirrored glass cubes on anodized aluminum in the AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas.[7]

In 2013, Fernández installed a show at Lehmann Maupin Chrystie Street titled "Night Writing," which consisted of an installation and a series of large works on paper created at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute. The work explored the idea of how humans have always looked up at the night sky for information, guidance, navigation and time-keeping. The title of the piece comes from an early form of braille which Fernández used to translate text that became a constellation pattern of perforated holes backed by mirrors – making the work a dynamic, reflective surface.

Fernández's largest solo exhibition to date, "As Above So Below" was recently on view at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts. Describing a universe in balance, the phrase "as above, so below" originates from the Vedas and is an idea central to ancient alchemy, in which every action occurring on one level of reality (physical, emotional, or mental) correlates to every other. Fernández applied this concept to scale, suggesting that the vast is present in the tiny and vice versa, a kind of "intimate immensity". Responding to MASS MoCA's massive and light-filled first-floor galleries, Fernández created landscape-like large-scale installations alongside palm-sized sculptures that embodied this expression. The show featured exploration of two-mined, subterranean minerals, gold and graphite, to depict cosmic and light-filled images that refer to the heavens, thus suggesting both the space above and below the viewer.

In 2013, Fernández was featured in a contemporary art installation in the Alfond Inn in Winter Park, FL, as a part of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum. The work on display is titled "Nocturnal (Cobalt Panorama), c. 2012."[8][9]

On June 1, 2015, "Fata Morgana" opened in New York's Madison Square Park. The Madison Square Park Conservancy presented the outdoor sculpture consisting of 500 running feet of golden, mirror-polished discs that create canopies above the pathways around the park's central Oval Lawn.[10]

In "Fata Morgana" I wanted to invert the traditional notion of outdoor sculpture by addressing all of the active walkways of the park to create an experiential, ambulatory art experience. By hovering over the park in a horizontal canopy, "Fata Morgana" becomes a ghost-like, sculptural, luminous mirage that distorts the landscape and becomes a reflective portrait of urban activity.[11]

In 2017, Fernández, in collaboration with Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, created a site-specific installation called "OVERLOOK: Teresita Fernández confronts Frederic Church at Olana" at Olana State Historic Site.[12][13] As part of the work, Fernández juxtaposes the works of landscape artists like Frederic Church, Marianne North, Martin Johnson Heade, among others, with images of indigenous people and their fellow travellers in order to examine and illustrate the context of the world that made up their images.[14]

Style and medium

At the core of Teresita Fernández's work is a paradox: she captures the essence of formless elements such as fire, water, and air using undeniably physical materials.[8]

Teresita Fernández is an artist well known for large-scale public sculptures and installations made from such diverse materials as thread, aluminum, acrylic, plastic, and glass beads. Although these are industrial materials, Fernández transforms them into forms and shapes that suggest natural phenomena such as waterfalls or sand dunes. This places her along a lineage of artist who explore the relationship between the power of nature and the development of technology.[8]

In her sculptures and drawings, Fernández often leverages non-traditional media to create optical illusions of motion, dissolution, and illumination. Fernández pairing of a conventional subject with an unconventional material reinforces her interest in combining the natural with the industrial or mass-produced.[8]

Japanese influences

In 1997, Fernández lived in Moriya, Ibaraki, during an artist's residency with Arcus Project. Fernández cites Japanese culture and sensibility as the greatest inspiration to her work as an artist.[2] Fernández states,

I think a huge part of me must be from Japan and it plays into my work, [particularly with] light and dark. [Like] light and shadows [or] seeing and not seeing. In fact most of my work [is what] that's all about – the idea that darkness, the revered beauty of shadows, is not really "just" dark emptiness, but that darkness is actually very much alive, dynamic. So it's about that reciprocity where darkness only exists where there's light and light only exists where there's darkness—they exist in tandem with one another, they define one another much more than being distant opposites.[2]

Fernández continues to visit Japan regularly during the last 18 years and cites her ongoing relationship with Japan as having a significant impact on her and her artwork:

There is something very particular in Japan that I recognized as oddly familiar and important. For me, the presence that inanimate objects have there is very similar to what art does. As a sculptor, it's very hard to make ordinary, physical materials that very much just want to be what they are, transcend themselves and have a charged presence that affects viewers on a visceral level.[2]

Honors

- Artist in Residencies

- 1997: Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation, The Space Program (New York, NY)

- 1997: Arcus Project (Moriya, Ibaraki, Japan)

- 1998: ArtPace (San Antonio, TX)

- 2005: The Fabric Workshop and Museum (Philadelphia, PA)

- 2010: STPI - Creative Workshop & Gallery (Singapore)

- 2011: John Hardy Residency Program (Bali, Indonesia)

- Awards

- 1994: CINTAS Fellowship[15]

- 1994: National Endowment for the Arts Artist's Grant

- 1995: Metro-Dade Cultural Consortium Grant (Miami, FL)

- 1995: National Foundation for Advancement in the Arts, CAVA Fellowship

- 1999: Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award

- 1999: American Academy in Rome Affiliated Fellowship (Rome, Italy)

- 2003: Guggenheim Fellowship (New York, NY)

- 2005: MacArthur Fellows Program[16]

- 2013: Aspen Art Museum Aspen Award for Art (Aspen, CO)

- 2016: Art in General Visionary Artist Honoree (New York, NY)[17]

- Membership

- 2011-2014: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts[18]

- 2016: U.S. Latinx Arts Futures Symposium, Project Director[19]

Recognition

In 2007, established curator Lisa Corrin of Northwestern University called Fernández "one of the best-kept secrets in the contemporary-art world."[20]

In 2011, President Obama appointed Fernández to the serve on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, a federal panel that advises the President, Congress, and governmental agencies on national matters of design and aesthetics. She is the first Latina to serve on the Commission, and the second person of Latino heritage to serve on the CFA in its over 100-year history. Forty years before her appointment, the last Cuban Ambassador to the United States Nicolas Arroyo sat on the panel from 1971 to 1976.

In May 2013, Fernández gave the keynote commencement speech at her alma mater, Virginia Commonwealth University. Fernández's address was called "On Amnesia, Broken Pottery, and the Inside of a Form." to the graduating class at her alma mater, Virginia Commonwealth University's School of the Arts, was cited by Maria Popova's blog Brain Pickings as one of the greatest commencement addresses of all time.

Fernández's speech highlighted the values of not giving up, accepting failure and change as a positive, and keeping integrity with accompanied success. Fernandez also offered ten tips for the graduates for help on the creative journey, including 1) Art requires time; 4) Not every project will survive; and 6) "When people say your work is good, do two things: first, don't believe them. Second, ask them, 'why?'"[21] One of the more significant quotes of the keynote speech helped provide insight into Fernández's philosophy that governs her artwork:

I was enamored with the idea of how what seemed broken, discarded, useless was transformed into a meaningful gesture… We are conditioned to think that what is broken is lost, or useless or a setback, and so when we set out with big ambitions we don't necessarily recognize what the next graduation is supposed to look like. Unlearning everything you learned in college is just an exercise in learning to recognize how the fragments and small bits lead to something that is much more than the sum of its parts.[21]

Fernández parting point could also be considered her most poignant – a reminder that being human is the wider circle within which being an artist resides, and that our art is always the combinatorial product of the fragments of who we are, of our combinatorial character.[21]

Being an artist is not just about what happens when you are in the studio. The way you live, the people you choose to love and the way you love them, the way you vote, the words that come out of your mouth… will also become the raw material for the art you make.[21]

Personal life

Fernández has lived and worked in Brooklyn, New York since 1997. She has two children.[20]

Selected solo exhibitions

- 1995: "Real/More Real." Museum of Contemporary Art (Miami, FL)

- 1996: Deitch Projects (New York, NY)

- 1997: Masataka Hayakawa Gallery (Tokyo, Japan)

- 1997: Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington, DC)

- 1998: Artpace (San Antonio, TX)

- 1999: Institute of Contemporary Art (Philadelphia, PA)

- 1999: "Borrowed Landscape." Deitch Projects (New York, NY)

- 2000: "supernova." Berkeley Art Museum/Matrix (Berkeley, CA)

- 2000: Site Santa-Fe(Santa Fe, NM)

- 2001: Galeria Helga de Alvear (Madrid, Spain)

- 2001: Castello di Rivoli (Turin, Italy)

- 2002: Miami Art Museum (Miami, FL)

- 2003: Grand Arts (Kansas City, MO)

- 2003: Galleria in Arco (Turin, Italy)

- 2003: Masataka Hayakawa Gallery (Tokyo, Japan)

- 2005: Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga (Málaga, Spain)

- 2005: Fabric Workshop and Museum (Philadelphia, PA)

- 2009: "Blind Landscape." Contemporary Art Museum, University of South Florida, (Tampa, FL); Blanton Museum of Art (Austin, TX)

- 2010: Galerie Almine Rech (Paris, France)

- 2010: Anthony Meier Fine Arts (San Francisco, CA)

- 2011: "Blind Landscape." Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland (Cleveland, OH)

- 2011: STPI (Singapore)

- 2011: "Focus: Teresita Fernández." Modern Art Museum (Fort Worth, TX)

- 2011: Gallery 313 (Seoul, Korea)

- 2011: "Pivot Points V." Museum of Contemporary Art (Miami, FL)

- 2012: "Night Writing." Lehmann Maupin (New York, NY)

- 2014: "As Above So Below." MASS MoCA (North Adams, MA)

- 2014: Kyoto University of Art and Design (Kyoto, Japan)

- 2014: Almine Rech (London, United Kingdom)

- 2015-2016: "Fata Morgana." Madison Square Park (New York, NY)[22][23][24]

- 2017: "OVERLOOK: Teresita Fernández confronts Frederic Church at Olana. A collaboration with the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros." Olana State Historic Site (Columbia County, New York)

Selected works

Bamboo Cinema

Bamboo Cinema

(2001) Bamboo Cinema (detail)

Bamboo Cinema (detail)

(2001)_deitch.jpg) Untitled (Pool)

Untitled (Pool)

(2005).jpg) Hothouse

Hothouse

(MoMA)

(2005) Fire

Fire

(2005)- Seattle Cloud Cover

(2006)  Seattle Cloud Cover (detail)

Seattle Cloud Cover (detail)

(2006) Blind Blue Landscape

Blind Blue Landscape

(2009) Blind Blue Landscape (detail)

Blind Blue Landscape (detail)

(2009) Stacked Waters

Stacked Waters

(2009) Stacked Waters (detail)

Stacked Waters (detail)

(2009)%2C2011.jpg) Untitled (Night Writing)

Untitled (Night Writing)

(2011).jpg) Night Writing (Hero and Leander)

Night Writing (Hero and Leander)

(2011).jpg) Drawn Waters (Borrowdale)

Drawn Waters (Borrowdale)

(2012) Black Sun

Black Sun

(2014)

Selected publications

- Steiner, Rochelle; Cardiff, Janet; Elíasson, Ólafur; Fernández, Teresita; Hendee, Stephen; Klaila, Bill; van Lieshout, Joep; Neto, Ernesto; Rist, Pipilotti; Schneider, Gregor; Steinkamp, Jennifer; Bruno, Giuliana (2000). Wonderland (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). St. Louis, MO: Saint Louis Art Museum. ISBN 978-0-891-78082-3. OCLC 908680661. – Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Saint Louis Art Museum, July 1-Sept. 24, 2000 - Fernández, Teresita (2001). Teresita Fernández (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Santa Fe, NM: SITE Santa Fe. OCLC 49221441. – Catalog of an exhibition held Oct. 7, 2000-Jan. 14, 2001 at SITE Santa Fe - Fernández, Teresita; Beccaria, Marcella (2001). Teresita Fernández (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help) (in Italian and English). Rivoli, Italy: Castello di Rivol. ISBN 978-0-970-07742-4. OCLC 52180953. – Catalog of an exhibition held at Castello di Rivoli, May 30-Aug. 26, 2001 - Momin, Shamim M.; Partegàs, Ester; Fernández, Teresita; Hendee, Stephen (2002). Outer City, Inner Space: Ester Partegãs, Stephen Hendee, Teresita Fernãndez (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). New York, NY: Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris. OCLC 231877422. - Fernández, Teresita; Volk, Gregory; Norr, David; Hauft, Amy; King, Elizabeth (2008). Teresita Fernández (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Richmond, VA: Reynolds Gallery. OCLC 231141945. - Miller, Margaret; Stringfield, Anne; Hickey, Dave; Norr, David Louis; Volk, Gregory; DiMeo Carlozzi, Annette (2009). Norr, David Louis, ed. Teresita Fernández: Blind Landscape (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Zurich: JRP Ringier. ISBN 978-3-037-64049-4. OCLC 466657380. - Fernández, Teresita; Rapaport, Brooke Kamin (Forward by); Adams, Beverly (2015). Fata Morgana (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). New York, NY: Madison Square Park Conservancy. OCLC 945215456. – Art installation exhibition held at Madison Square Park, New York, New York, June 1, 2015 – January 10, 2016 - Brielmaier, Isolde; Dopico, Ana; Fernández, Teresita; Hinton, David; King, Elizabeth; Markonish, Denise (2017). Markonish, Denise, ed. Teresita Fernández: Wayfinding. New York, NY: DelMonico Books/Prestel. ISBN 978-3-791-35682-2. OCLC 976036344.

References

- ↑ Slenske, Michael (30 September 2013). "Teresita Fernández Artworks at Lehman Maupin, Hong Kong, and Mass MoCA". Architectural Digest.

- 1 2 3 4 Roffino, Sara (15 July 2014). "Teresita Fernández with Sara Roffino". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ↑ Garcia, Patricia (23 September 2016). "Can Someone Mail a Copy of Nuevo New York to Donald Trump?". Vogue.

- ↑ Miller, Margaret; Stringfield, Anne; Hickey, Dave; Norr, David Louis; Volk, Gregory; DiMeo Carlozzi, Annette (2009). Norr, David Louis, ed. Teresita Fernández: Blind Landscape (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Zurich: JRP Ringier. ISBN 978-3-037-64049-4. OCLC 466657380. - ↑ Fernández, Teresita (11 August 2011). "Teresita Fernández, Stacked Waters" (Video). Blanton Museum of Art.

- ↑ "Teresita Fernández: Stacked Waters – Austin's Blanton Museum of Art". Blanton Museum of Art. 2009.

- ↑ Cheek, Lawrence W.; Daniels, Brett; Pagel, David (2010). Dallas Cowboys Art Collection: Art + Architecture at AT&T Stadium (PDF). Arlington, TX. p. 23. OCLC 657077503.

- 1 2 3 4 Lawrence Alfond, Barbara; Ross Goodman, Abigail; Heller, Ena (2013). Ross Goodman, Abigail, ed. Art for Rollins: The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art. Volume I (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Winter Park, FL: Cornell Fine Arts Museum. ISBN 978-0-979-22802-5. OCLC 903361166. - ↑ DiazCasas, Rafael (27 August 2013). "Close-Up: Nocturnal (Navigation) by Teresita Fernández". Cuban Art News.

- ↑ Kino, Carol (31 March 2015). "Artist Teresita Fernández Transforms New York's Madison Square Park". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Things to Do: Mad. Sq. Art: Teresita Fernández

- ↑ "OVERLOOK: Teresita Fernández confronts Frederic Church at Olana A collaboration with the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros". Olana NY State Historic Site. 14 May 2017.

- ↑ Hasbrook, Melanie; Barrera Pieck, Mariana (22 February 2017). ""OVERLOOK" Exhibition at Olana Features a Groundbreaking Site-Specific Installation by Artist Teresita Fernández" (Press release).

- ↑ Halperin, Julia (2 March 2017). "Teresita Fernandez wants to change the way you think about American landscapes". The Art Newspaper.

- ↑ "Fellows in Visual Arts: Fernández, Teresita (1994-95)". CINTAS Foundation. 1994.

- ↑ "MacArthur Fellows. Meet the Class of 2005: Teresita Fernández". MacArthur Foundation. 1 September 2005.

- ↑ "Visionary Awards 2016: 35th Anniversary Gala". Art in General. 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "Teresita Fernández: CFA Service: 2011–2014". U.S. Commission of Fine Arts.

- ↑ Fernández, Teresita (9 November 2016). "Teresita Fernández, Welcome Remarks" (Video). U.S. Latinx Arts Futures Symposium.

- 1 2 Stringfield, Anne (April 2007). "People Are Talking About: Art. The Dazzle: Teresita Fernández makes art that is structurally elegant, thoughtfully compelling, and absolutely luminous" (PDF). Vogue. p. 270.

- 1 2 3 4 Popova, Maria (29 December 2014). "What It Really Takes to Be an Artist: MacArthur Genius Teresita Fernández's Magnificent Commencement Address". Brain Pickings.

- ↑ "Teresita Fernández: Fata Morgana" (Press release). Madison Square Park Conservancy. 1 June 2015.

- ↑ "Teresita Fernández: Fata Morgana in Madison Square Park" (Video). Madison Square Park Conservancy. 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Guilfoyle, Ultan (17 November 2015). "Teresita Fernández, "Fata Morgana"" (Video). Lehmann Maupin.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teresita Fernández. |

- Teresita Fernández at Lehmann Maupin

- Teresita Fernández at Anthony Meier Fine Art (AMFA)