The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (竹取物語 Taketori Monogatari) is a 10th-century Japanese monogatari (fictional prose narrative) containing Japanese folklore. It is considered the oldest extant Japanese prose narrative[1][2] although the oldest manuscript dates to 1592.[3]

The tale is also known as The Tale of Princess Kaguya (かぐや姫の物語 Kaguya-hime no Monogatari), after its protagonist.[4] It primarily details the life of a mysterious girl called Kaguya, who was discovered as a baby inside the stalk of a glowing bamboo plant.

Narrative

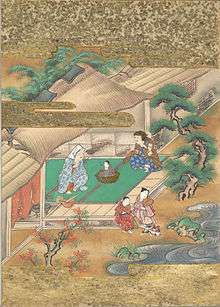

One day, while walking in the bamboo forest, an old, childless bamboo cutter called Taketori no Okina (竹取翁 "the Old Man who Harvests Bamboo") came across a mysterious, shining stalk of bamboo. After cutting it open, he found inside it an infant the size of his thumb. He rejoiced to find such a beautiful girl and took her home. He and his wife raised her as their own child and named her Kaguya-hime (かぐや姫 accurately, Nayotake no Kaguya-hime, "Shining princess of the supple bamboo"). Thereafter, Taketori no Okina found that whenever he cut down a stalk of bamboo, inside would be a small nugget of gold. Soon he became rich. Kaguya-hime grew from a small baby into a woman of ordinary size and extraordinary beauty. At first, Taketori no Okina tried to keep her away from outsiders, but over time the news of her beauty spread.

Eventually, five princes came to Taketori no Okina's residence to ask for the beautiful Kaguya-hime's hand in marriage. The princes eventually persuaded Taketori no Okina to tell a reluctant Kaguya-hime to choose from among them. Kaguya-hime concocted impossible tasks for the princes, agreeing to marry the one who managed to bring her his specified item. That night, Taketori no Okina told the five princes what each must bring. The first was told to bring her the stone begging bowl of the Buddha Shakyamuni from India, the second a jeweled branch from the mythical island of Hōrai,[5] the third the legendary robe of the fire-rat of China, the fourth a colored jewel from a dragon's neck, and the final prince a cowry shell born of swallows.

Realizing that it was an impossible task, the first prince returned with an expensive stone bowl, hoping that Kaguya-hime would believe it to be real, but after noticing that the bowl did not glow with holy light, Kaguya-hime saw through his deception. Likewise, two other princes attempted to deceive her with fakes, but also failed. The fourth gave up after encountering a storm, while the final prince lost his life (severely injured in some versions) in his attempt.

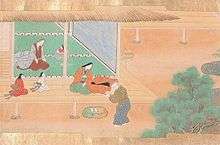

After this, the Emperor of Japan, Mikado, came to see the strangely beautiful Kaguya-hime and, upon falling in love, asked her to marry him. Although he was not subjected to the impossible trials that had thwarted the princes, Kaguya-hime rejected his request for marriage as well, telling him that she was not of his country and thus could not go to the palace with him. She stayed in contact with the Emperor, but continued to rebuff his requests and marriage proposals.

That summer, whenever Kaguya-hime saw the full moon, her eyes filled with tears. Though her adoptive parents worried greatly and questioned her, she was unable to tell them what was wrong. Her behaviour became increasingly erratic until she revealed that she was not of this world and must return to her people on the Moon. In some versions of this tale, it is said that she was sent to the Earth, where she would inevitably form material attachment, as a temporary punishment for some crime, while in others, she was sent to Earth for her own safety during a celestial war. The gold that Taketori no Okina had been finding had in fact been a stipend from the people of the Moon, sent down to pay for Kaguya-hime's upkeep.

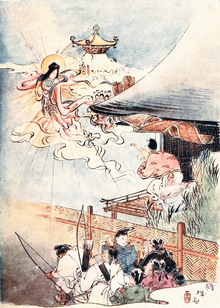

As the day of her return approached, the Emperor sent many guards around her house to protect her from the Moon people, but when an embassy of "Heavenly Beings" arrived at the door of Taketori no Okina's house, the guards were blinded by a strange light. Kaguya-hime announced that, though she loved her many friends on Earth, she must return with the Moon people to her true home. She wrote sad notes of apology to her parents and to the Emperor, then gave her parents her own robe as a memento. She then took a little of the elixir of life, attached it to her letter to the Emperor, and gave it to a guard officer. As she handed it to him, her feather robe was placed on her shoulders, and all of her sadness and compassion for the people of the Earth were apparently forgotten. The heavenly entourage took Kaguya-hime back to Tsuki no Miyako (月の都; lit. "the Capital of the Moon"), leaving her earthly foster parents in tears.

The parents became very sad and were soon put to bed sick. The officer returned to the Emperor with the items Kaguya-hime had given him as her last mortal act, and reported what had happened. The Emperor read her letter and was overcome with sadness. He asked his servants, "Which mountain is the closest place to Heaven?", to which one replied the Great Mountain of Suruga Province. The Emperor ordered his men to take the letter to the summit of the mountain and burn it, in the hope that his message would reach the distant princess. The men were also commanded to burn the elixir of immortality since the Emperor did not wish to live forever without being able to see her. The legend has it that the word immortality, 不死 (fushi), became the name of the mountain, Mount Fuji. It is also said that the kanji for the mountain, 富士山 (literally "Mountain Abounding with Warriors"), are derived from the Emperor's army ascending the slopes of the mountain to carry out his order. It is said that the smoke from the burning still rises to this day. (In the past, Mount Fuji was much more volcanically active and therefore produced more smoke.)

Literary connections

Elements of the tale were drawn from earlier stories. The protagonist Taketori no Okina, given by name, appears in the earlier poetry collection Man'yōshū (c. 759; poem# 3791). In it, he meets a group of women to whom he recites a poem. This indicates that there previously existed an image or tale revolving around a bamboo cutter and celestial or mystical women.[6][7]

A similar retelling of the tale appears in the c. 12th century Konjaku Monogatarishū (volume 31, chapter 33), although their relation is under debate.[8]

Banzhu Guniang

In 1957, Jinyu Fenghuang (金玉鳳凰), a Chinese book of Tibetan tales, was published.[9] In early 1970s, Japanese literary researchers became aware that "Banzhu Guniang" (班竹姑娘), one of the tales in the book, had certain similarities with The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.[10][11] Initially, many researchers thought that "Banzhu Guniang" must be related to Tale of Bamboo Cutter, although some were skeptical.

In 1980s, studies showed that the relationship is not as simple as initially thought. Okutsu provides extensive review of the research, and notes that the book Jinyu Fenghuang was intended to be for children, and as such, the editor took some liberties in adapting the tales. No other compilation of Tibetan tales contains the story.[12]

A Tibet-born person wrote that he did not know the story.[13] A researcher went to Sichuan and found that, apart from those who had already read "Jinyu Fenghuang", local researchers in Chengdu did not know the story.[14] Tibetan informants in Ngawa Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture did not know the story either.[14]

Legacy

The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter has been identified as proto-science fiction. Some of its science fiction plot elements include Kaguya-hime being a princess from the Moon who is sent to Earth for safety during a celestial war, an extraterrestrial being raised by a human on Earth, and her being taken back to the Moon by her real extraterrestrial family. A manuscript illustration also depicts a round flying machine that resembles a flying saucer.[15]

Adaptations

The 1974 Japanese TV series Ultraman Leo episode 32 "Japan Masterpiece Folklore Series: Farewell, Princess Kaguya" features a teen age girl who does not know she is the moon princess, sent to Earth 15 years ago to protect her from enemies who wanted her dead, until Kirara a giant creature from the moon comes to Earth to take her home now that her enemies have been defeated.

The 1975 Japanese TV series Manga Nihon Mukashi-Banashi (Cartoon Tales of Old Japan) contains a 10-minute adaption of the story, directed by Takao Kodama with animation by Masakazu Higuchi and art by Koji Abe.[16]

Kon Ichikawa made a film of the story in 1987 entitled Princess from the Moon. Composer Robert Moran saw it and composed an opera based on it, From the Towers of the Moon.

The tale was also featured in the 1989 film Big Bird in Japan, where Big Bird first is told the tale as folklore, and later realizes that his guide, named Kaguya, is the girl from the tale, but he is too late to see her return to the moon, and assumes that his imagination got away from him again.

In 1988, Japanese composer Maki Ishii asked Czech choreographer Jiří Kylián to produce a ballet for his musical work bearing the name Princess Kaguya. The product was a contemporary ballet named Kaguyahime the Moon Princess, where elements of Western and Japanese cultures combine.

A demon assuming the identity of Kaguya, claiming to have devoured the real Kaguya Hime to acquire her divinity, is an antagonist in Inuyasha the Movie: The Castle Beyond the Looking Glass.

In the 2006 Clover Studio video game Ōkami, a girl named Kaguya appears as a captive of the possessed Emperor, and when she is freed, she reunites with her grandfather, who found her as a baby in a bamboo grove, and then announces that she must depart the land of Nippon to return to the moon. However, in this version, she uses a rocket ship to depart, and her design motif mixes bamboo designs with rabbit-like ears made of leaves, suggesting that she's a moon rabbit turned human.

Studio Ghibli released in November 2013 in Japan an anime film based on the folktale under the title of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.[17]

In Touhou Project, the Character Houraisan Kaguya[18] is a princess born over a thousand years ago on the moon. She was raised with utmost care as a princess, thus she eventually became selfish and managed to convince Yagokoro Erin[19] to illegally create the Hourai Elixir (Elixir of Life) out of self-interest and consumed it. Kaguya was executed again and again but as an immortal, she could not die. Hence, the Lunarians exiled her to Earth and she was found in the Shining Bamboo by her adopted father. Kaguya's backstory then follows the original folktale of The Bamboo Cutter. The name of her theme in-game is called "Flight of the Bamboo Cutter ~ Lunatic Princess"[20] and the five Impossible Requests she requested of the five princes are revealed to already be in her possession as she attacks the player with them as the final boss in Imperishable Night.

Kaguya Otsutsuki is the otherworldly antagonist in the popular Naruto series, the ancestor of the half-human branch Otsutsuki clan through her twin sons Hagoromo in the Senju and Uchiha clans and Hamura in the Hyuga clan and Toneri Otsutsuki from The Last: Naruto the Movie. She is also a playable character in Naruto: Shippuden: Ultimate Ninja Storm 4.

In the manga series Kaguya-sama: Love is War, most of the major characters have their names derived from the story (both from characters and the impossible tasks), with several chapters making a direct reference to the original tale.

In the manga series Soul Eater, Kaguya is one of the Clown constructs created by Asura as his first line of defense.

Notes

- ↑ "Japan: Literature", Windows on Asia, MSU ,

- ↑ "17. A Picture Contest". The Tale of Genji.

the ancestor of all romances

) - ↑ Katagiri et al. 1994: 95.

- ↑ Katagiri et al. 1994: 81.

- ↑ McCullough, Helen Craig (1990). Classical Japanese Prose. Stanford University Press. pp. 30, 570. ISBN 978-0-8047-1960-5.

- ↑ Horiuchi (1997:345-346)

- ↑ Satake (2003:14-18)

- ↑ Yamada (1963:301-303)

- ↑ 田海燕, ed. (1957). 金玉鳳凰 (in Chinese). Shanghai: 少年兒童出版社.

- ↑ 百田弥栄子 (1971). 竹取物語の成立に関する一考察. アジア・アフリカ語学院紀要 (in Japanese). 3.

- ↑ 伊藤清司 (1973). かぐや姫の誕生―古代説話の起源 (in Japanese). 講談社.

- ↑ 奥津 春雄 (2000). 竹取物語の研究: 達成と変容 竹取物語の研究 (in Japanese). 翰林書房. ISBN 978-4-87737-097-8.

- ↑ テンジン・タシ, ed. (2001). 東チベットの民話 (in Japanese). Translated by 梶濱 亮俊. SKK.

- 1 2 繁原 央 (2004). 日中説話の比較研究 (in Japanese). 汲古書院. ISBN 978-4-7629-3521-3.

- ↑ Richardson, Matthew (2001). The Halstead Treasury of Ancient Science Fiction. Rushcutters Bay, New South Wales: Halstead Press. ISBN 978-1-875684-64-9. (cf. "Once Upon a Time". Emerald City (85). September 2002. Retrieved 2008-09-17. )

- ↑ The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Pelleas. Retrieved 2014-10-04.

- ↑ "Kaguya-hime monogatari" (in Japanese). JP. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ↑ https://en.touhouwiki.net/wiki/Kaguya_Houraisan

- ↑ https://en.touhouwiki.net/wiki/Eirin_Yagokoro

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4w5s7dwrH7Q

References

- Katagiri Yōichi, Fukui Teisuke, Takahashi Seiji and Shimizu Yoshiko. 1994. Taketori Monogatari, Yamato Monogatari, Ise Monogatari, Heichū Monogatari in Shinpen Nihon Koten Bungaku Zenshū series. Tokyo: Shogakukan.

- Donald Keene (translator), The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, ISBN 4-7700-2329-4

- Japan at a Glance Updated, ISBN 4-7700-2841-5, pages 164—165 (brief abstract)

- Fumiko Enchi, "Kaguya-hime", ISBN 4-265-03282-6 (in Japanese hiragana)

- Horiuchi, Hideaki; Akiyama Ken (1997). Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 17: Taketori Monogatari, Ise Monogatari (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 978-4-00-240017-4.

- Satake, Akihiro; Yamada Hideo; Kudō Rikio; Ōtani Masao; Yamazaki Yoshiyuki (2003). Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 4: Man'yōshū (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 978-4-00-240004-4.

- Taketori monogatari, Japanese Text Initiative, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library

- Yamada, Yoshio; Yamda Tadao; Yamda Hideo; Yamada Toshio (1963). Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 26: Konjaku Monogatari 5 (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 978-4-00-060026-2.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. |

- Ryukoku University exhibition

- Tetsuo Kawamoto: The Moon Princess (translated by Clarence Calkins)