Breast reconstruction

| Breast reconstruction | |

|---|---|

Result of breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Nipple missing, and cicatrix (scar) is prominent. | |

| Specialty | plastic surgeon |

Breast reconstruction is the rebuilding of a breast, usually in women. It involves using autologous tissue or prosthetic material to construct a natural-looking breast. Often this includes the reformation of a natural-looking areola and nipple. This procedure involves the use of implants or tissue taken from other parts of the woman's body.

Generally, the aesthetic appearance is acceptable to the woman, but the reconstructed area is commonly completely numb afterwards, which results in loss of sexual function as well as the ability to perceive pain caused by burns and other injuries.[1]

Timing

The primary part of the procedure can often be carried out immediately following the mastectomy. As with many other surgeries, patients with significant medical comorbidities (high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes) and smokers are higher-risk candidates. Surgeons may choose to perform delayed reconstruction to decrease this risk. There is little evidence available from randomised studies to favour immediate or delayed reconstruction.[2] The infection rate may be higher with primary reconstruction (done at the same time as mastectomy), but there are psychologic and financial benefits to having a single primary reconstruction. Patients expected to receive radiation therapy as part of their adjuvant treatment are also commonly considered for delayed autologous reconstruction due to significantly higher complication rates with tissue expander-implant techniques in those patients. Waiting for six months to a year following may decrease the risk of complications, but this risk will always be higher in patients who have received radiation therapy.

Delayed breast reconstruction is considered more challenging than immediate reconstruction. Frequently not just breast volume, but also skin surface area needs to be restored. Many patients undergoing delayed breast reconstruction have been previously treated with radiation or have had a reconstruction failure with immediate breast reconstruction. In nearly all cases of delayed breast reconstruction tissue must be borrowed from another part of the body to make the new breast.[3]

Breast reconstruction is a large undertaking that usually takes multiple operations. Sometimes these follow-up surgeries are spread out over weeks or months. If an implant is used, the individual runs the same risks and complications as those who use them for breast augmentation but has higher rates of capsular contracture (tightening or hardening of the scar tissue around the implant) and revisional surgeries.[4]

Techniques

There are many methods for breast reconstruction. The two most common are:

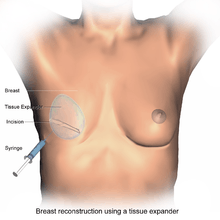

- Tissue Expander - Breast implants This is the most common technique used worldwide. The surgeon inserts a tissue expander, a temporary silastic implant, beneath a pocket under the pectoralis major muscle of the chest wall.[5][6] The pectoral muscles may be released along its inferior edge to allow a larger, more supple pocket for the expander at the expense of thinner lower pole soft tissue coverage. The use of acellular human or animal dermal grafts have been described as an onlay patch to increase coverage of the implant when the pectoral muscle is released, which purports to improve both functional and aesthtic outcomes of implant-expander breast reconstruction.[7][8]

- Typically done in the same procedure of a mastectomy, a tissue expander is placed in the sub-pectoral pocket more colloquially considered to be under the chest tissue. Over the course of a few months saline solution is injected into a tube inside of the expander, which allows for the expansion of the tissue until the tissue is stretched to the appropriate size. Following operations provide for the removal of the expander, placement of a permanent implant and areolar reconstruction.[9]

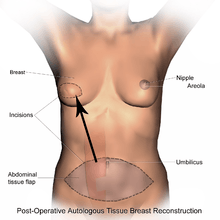

- Flap reconstruction The second most common procedure uses tissue from other parts of the patient's body, such as the back, buttocks, thigh or abdomen. This procedure may be performed by leaving the donor tissue connected to the original site to retain its blood supply (the vessels are tunnelled beneath the skin surface to the new site) or it may be cut off and new blood supply may be connected.[10]

- The latissimus dorsi muscle flap is the donor tissue available on the back. It is a large flat muscle which can be employed without significant loss of function. It can be moved into the breast defect while still attached to its blood supply under the arm pit (axilla). A latissimus flap is usually used to recruit soft-tissue coverage over an underlying implant. Enough volume can be recruited occasionally to reconstruct small breasts without an implant. The latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction flap has a number of advantages, but despite the advances in surgical techniques, it has remained vulnerable to skin dehiscence or necrosis at the donor site (on the back). The Mannu flap is a form of latissimus dorsi flap which avoids this complication by preserving a generous subcutaneous fat layer at the donor site and has been shown to be a safe, simple and effective way of avoiding wound dehiscence at the donor site after extended latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction.[11]

- Abdominal flaps The abdominal flap for breast reconstruction is the TRAM flap (Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous flap) or its technically distinct variants of microvascular "perforator flaps" like the DIEP/SIEA flaps. In a TRAM procedure, a portion of the abdomen tissue group, including skin, adipose tissues, minor muscles and connective tissues, is taken from the patient's abdomen and transplanted onto the breast site. Both TRAM and DIEP/SIEA use the abdominal tissue between the umbilicus and the pubis. The DIEP flap and free-TRAM flap require advanced microsurgical technique and are less common as a result. Both can provide enough tissue to reconstruct large breasts. These procedures are preferred by some breast cancer patients because they result in an abdominoplasty (tummy tuck), and allow the breast to be reconstructed with one's own tissues instead of a foreign implant. TRAM flap procedures may weaken the abdominal wall and torso strength, but are tolerated well in most patients. To prevent muscle weakness and incisional hernias, the portion of abdominal wall exposed by reflection of the rectus abdominis muscle may be strengthened by a piece of surgical mesh placed over the defect and sutured in place. Perforator techniques such as the DIEP (deep inferior epigastric perforator) flap and SIEA (superficial inferior epigastric artery) flap require precise dissection of small perforating vessels through the rectus muscle, and purport the advantage of less weakening of the abdominal wall, though rectus abdominus muscle function may still be compromised. Other total autologous tissue breast reconstruction donor sites include the buttocks (superior or inferior gluteal artery perforator flaps (SGAP or IGAP)). The purpose of perforator flaps (DIEP, SIEA, SGAP, IGAP) is to provide sufficient skin and fat for an aesthetic reconstruction while minimizing morbidity from harvesting the underlying muscles. DIEP reconstruction generally produces the best outcome for most women.[12] See free flap breast reconstruction for more information.

- Mold-assisted reconstruction Made using laser scanning and 3D printing, a patient-specific silicone mold can be used as an aid during surgery. It is used as a guide for orienting and shaping the flap to improve accuracy and symmetry.[13]

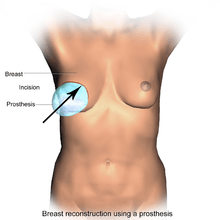

- Direct to Implant ("One-Step") Breast Reconstruction Post-mastectomy reconstruction with a direct to implant, or "one-step" approach allows for a single-stage reconstruction of the breast mound in select patients. This approach is best suited for patients with good preservation of the breast skin after mastectomy. A permanent implant is inserted immediately following the mastectomy, forgoing the initial placement of a tissue expander and subsequent expansion process. At the time of the initial post mastectomy reconstruction operation, the implant is positioned on the chest wall behind the pectoralis major muscle. Today, with the use of a dermal matrix (such as AlloDerm®), the surgeon can frequently use a permanent implant of the desired definitive volume during the initial surgery, provided the amount and quality of the breast skin remaining after mastectomy can accommodate the volume. The patient will have the definitive breast volume and approximate shape after the first operation. Depending on the quality of the result after allowing the initial reconstruction to settle and heal for a few months, a second stage reconstruction creating a more refined breast shape may still be desirable. This is an outpatient procedure that involves minor refinements in contour and symmetry potentially without exchanging the implant. The initial implant placement, and possible second stage, each take about one hour in the operating room.[14]

A Cochrane review published in 2016 concluded that implants for use in breast reconstructive surgery have not been adequately studied in good quality clinical trials. "These days - even after a few million women have had breasts reconstructed - surgeons cannot inform women about the risks and complications of different implant-based breast reconstructive options on the basis of results derived from Randomized Controlled Trials."[15]

Other considerations

To restore the appearance of the breast with surgical reconstruction, there are a few options regarding the nipple and areola.

- A nipple prosthesis can be used to restore the appearance of the reconstructed breast. Impressions can be made and photographs can be used to accurately replace the nipple lost with some types of mastectomies. This can be instrumental in restoring the psychological well-being of the breast cancer survivor. The same process can be used to replicate the remaining nipple in cases of a single mastectomy. Ideally, a prosthesis is made around the time of the mastectomy and it can be used just weeks after the surgery.

- Nipple reconstruction is usually delayed until after the breast mound reconstruction is completed so that the positioning can be planned precisely. There are several methods of reconstructing the nipple-areolar complex, including:

- Nipple-Areolar Composite Graft (Sharing) - if the contralateral breast has not been reconstructed and the nipple and areolar are sufficiently large, tissue may be harvested and used to recreate the nipple-areolar complex on the reconstructed side.

- Local Tissue Flaps - a nipple may be created by raising a small flap in the target area and producing a raised mound of skin. To create an areola, a circular incision may be made around the new nipple and sutured back again. The nipple and areolar region may then be tattooed to produce a realistic colour match with the contralateral breast.

- Local Tissue Flaps With Use of AlloDerm - as above, a nipple may be created by raising a small flap in the target area and producing a raised mound of skin. AlloDerm (cadaveric dermis) can then be inserted into the core of the new nipple acting like a "strut" which may help maintain the projection of the nipple for a longer period of time. The nipple and areolar region may then be tattooed later.[16] There are however some important issues in relation to NAC Tattooing that should be considered prior to opting for tattooing, such as the choice of pigments and equipment used for the procedure.[17]

Outcomes

The typical outcome of breast reduction surgery is a breast mound with a pleasing aesthetic shape, with a texture similar to a natural breast, but which feels completely or mostly numb for the woman herself.[1] This loss of sensation, called somatosensory loss or the inability to perceive touch, heat, cold, and pain, sometimes results in women burning themselves or injuring themselves without noticing, or not noticing that their clothing has shifted to expose their breasts.[1] "I can't even feel it when my kids hug me," said one mother, who had nipple-sparing breast reconstruction after a bilateral mastectomy.[1] The loss of sensation has long-term medical consequences, because it makes the affected women unable to feel itchy rashes, infected sores, cuts, bruises, or situations that risk sunburns or frostbite on the affected areas.

More than half of women treated for breast cancer develop upper quarter dysfunction, including limits on how well they can move, pain in the breast, shoulder or arm, lymphedema, loss of sensation, and impaired strength.[18] The risk of dysfunction is higher among women who have breast reconstruction surgery.[18] One in three have complications, one in five need further surgery and the procedure fails in 5%.[19]

Some methods have specific side effects. The transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap method results in weakness and loss of flexibility in the abdominal wall.[20] Reconstruction with implants have a higher risk of long-term pain.[18]

Outcomes-based research on quality of life improvements and psychosocial benefits associated with breast reconstruction [21][22] served as the stimulus in the United States for the 1998 Women's Health and Cancer Rights Act, which mandated that health care payer cover breast and nipple reconstruction, contralateral procedures to achieve symmetry, and treatment for the sequelae of mastectomy.[23] This was followed in 2001 by additional legislation imposing penalties on noncompliant insurers. Similar provisions for coverage exist in most countries worldwide through national health care programs.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Rabin, Roni Caryn (2017-01-29). "After Mastectomies, an Unexpected Blow: Numb New Breasts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ d'Souza, Nigel; Darmanin, Geraldine; Fedorowicz, Zbys (2011). "Immediate versus delayed reconstruction following surgery for breast cancer". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008674. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008674.pub2. PMID 21735435.

- ↑ "Breast Reconstruction: Immediate or Delayed".

- ↑ "Breast reconstruction using body tissue." Breast cancer | Lets Beat Cancer! Cancer Research UK, 18 Aug. 2016. Web. 05 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Mannu, Gurdeep S.; Navi, Ali; Hussien, Maged (2015). "Sentinel lymph node biopsy before mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction does not significantly delay surgery in early breast cancer". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 85 (6): 438–43. doi:10.1111/ans.12603. PMID 24754896.

- ↑ Mannu, G.S.; Navi, A.; Morgan, A.; Mirza, S.M.; Down, S.K.; Farooq, N.; Burger, A.; Hussien, M.I. (2012). "Sentinel lymph node biopsy before mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction may predict post-mastectomy radiotherapy, reduce delayed complications and improve the choice of reconstruction". International Journal of Surgery. 10 (5): 259–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.04.010. PMID 22525383.

- ↑ Breuing, Karl H.; Warren, Stephen M. (2005). "Immediate Bilateral Breast Reconstruction with Implants and Inferolateral AlloDerm Slings". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 55 (3): 232–9. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000168527.52472.3c. PMID 16106158.

- ↑ Salzberg, C Andrew (2006). "Nonexpansive Immediate Breast Reconstruction Using Human Acellular Tissue Matrix Graft (AlloDerm)". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 57 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000214873.13102.9f. PMID 16799299.

- ↑ "Tissue Expanders". hopkinsmedicine.org.

- ↑ "Breast cancer | Breast reconstruction using body tissue | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org.

- ↑ Mannu, Gurdeep S.; Farooq, Naheed; Down, Sue; Burger, Amy; Hussien, Maged I. (2013). "Avoiding back wound dehiscence in extended latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 83 (5): 359–64. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06292.x. PMID 23088555.

- ↑ Erić, M.; Mihić, N.; Krivokuća, D. (2009-03-01). "Breast reconstruction following mastectomy; patient's satisfaction". Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 109 (2): 159–166. ISSN 0001-5458. PMID 19499674.

- ↑ Melchels, Ferry; Wiggenhauser, Paul Severin; Warne, David; Barry, Mark; Ong, Fook Rhu; Chong, Woon Shin; Hutmacher, Dietmar Werner; Schantz, Jan-Thorsten (2011). "CAD/CAM-assisted breast reconstruction". Biofabrication. 3 (3): 034114. Bibcode:2011BioFa...3c4114M. doi:10.1088/1758-5082/3/3/034114. PMID 21900731.

- ↑ Cassileth, Lisa; Kohanzadeh, Soma; Amersi, Farin (August 2012). "One-Stage Immediate Breast Reconstruction With Implants: A New Option for Immediate Reconstruction". Annals of Plastic Surgery: 134–8. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182250c60. PMID 21734545.

- ↑ Rocco, Nicola; Rispoli, Corrado; Moja, Lorenzo; Amato, Bruno; Iannone, Loredana; Testa, Serena; Spano, Andrea; Catanuto, Giuseppe; Accurso, Antonello; Nava, Maurizio B (2016). "Different types of implants for reconstructive breast surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010895. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010895.pub2. PMID 27182693.

- ↑ Garramone, Charles E.; Lam, Benjamin (2007). "Use of AlloDerm in Primary Nipple Reconstruction to Improve Long-Term Nipple Projection". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 119 (6): 1663–8. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000258831.38615.80. PMID 17440338.

- ↑ A. Darby. 3D Nipple Tattooing a New Service? (inc revisions). CosmeticTattoo.org Educational Articles 24/10/2013

- 1 2 3 McNeely, Margaret L.; Binkley, Jill M.; Pusic, Andrea L.; Campbell, Kristin L.; Gabram, Sheryl; Soballe, Peter W. (2012-04-15). "A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: postoperative and postreconstructive issues". Cancer. 118 (8 Suppl): 2226–2236. doi:10.1002/cncr.27468. ISSN 1097-0142. PMID 22488697.

- ↑ "One in Three Women Undergoing Breast Reconstruction Have Complications". Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ↑ Atisha, Dunya; Alderman, Amy K. (2009-08-01). "A systematic review of abdominal wall function following abdominal flaps for postmastectomy breast reconstruction". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 63 (2): 222–230. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e31818c4a9e. ISSN 1536-3708. PMID 19593108.

- ↑ Harcourt, Diana M.; Rumsey, Nichola J.; Ambler, Nicholas R.; Cawthorn, Simon J.; Reid, Clive D.; Maddox, Paul R.; Kenealy, John M.; Rainsbury, Richard M.; Umpleby, Harry C. (2003). "The Psychological Effect of Mastectomy with or without Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective, Multicenter Study". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 111 (3): 1060–8. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000046249.33122.76. PMID 12621175.

- ↑ Brandberg, Yvonne; Malm, Maj; Blomqvist, Lennart (2000). "A Prospective and Randomized Study, 'SVEA,' Comparing Effects of Three Methods for Delayed Breast Reconstruction on Quality of Life, Patient-Defined Problem Areas of Life, and Cosmetic Result". Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 105 (1): 66–74, discussion 75–6. doi:10.1097/00006534-200001000-00011. PMID 10626972.

- ↑ http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/publications/whcra.html%5Bfull+citation+needed%5D

External links

- Breast Reconstruction Following Breast Removal from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

- National Cancer Institute breast cancer page

- US Dept. of Labor - Women's Health & Cancer Rights Act of 1998

- Plastic Surgery Stirs a Debate

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Breast reconstruction. |