TOP500

The TOP500 project ranks and details the 500 most powerful non-distributed computer systems in the world. The project was started in 1993 and publishes an updated list of the supercomputers twice a year. The first of these updates always coincides with the International Supercomputing Conference in June, and the second is presented at the ACM/IEEE Supercomputing Conference in November. The project aims to provide a reliable basis for tracking and detecting trends in high-performance computing and bases rankings on HPL,[1] a portable implementation of the high-performance LINPACK benchmark written in Fortran for distributed-memory computers.

China currently dominates the list with 206 supercomputers, leading the second place (United States) by a record margin of 82.[2] In the most recent list (June 2018), the American Summit is the world's most powerful supercomputer, reaching 122.3 petaFLOPS on the LINPACK benchmarks.

The TOP500 list is compiled by Jack Dongarra of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Erich Strohmaier and Horst Simon of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), and from 1993 until his death in 2014, Hans Meuer of the University of Mannheim, Germany.

History

In the early 1990s, a new definition of supercomputer was needed to produce meaningful statistics. After experimenting with metrics based on processor count in 1992, the idea arose at the University of Mannheim to use a detailed listing of installed systems as the basis. In early 1993, Jack Dongarra was persuaded to join the project with his LINPACK benchmarks. A first test version was produced in May 1993, partly based on data available on the Internet, including the following sources:[3][4]

- "List of the World's Most Powerful Computing Sites" maintained by Gunter Ahrendt[5]

- David Kahaner, the director of the Asian Technology Information Program (ATIP);[6] published a report in 1992, titled "Kahaner Report on Supercomputer in Japan"[4] which had an immense amount of data.

The information from those sources was used for the first two lists. Since June 1993, the TOP500 is produced bi-annually based on site and vendor submissions only.

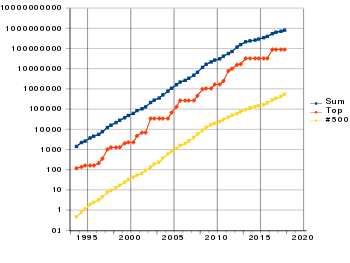

Since 1993, performance of the No. 1 ranked position has grown steadily in accordance with Moore's law, doubling roughly every 14 months. As of June 2018, Summit was fastest with an Rpeak[7] of 187.6593 PFLOPS. For comparison, this is over 1,432,513 times faster than the Connection Machine CM-5/1024 (1,024 cores), which was the fastest system in November 1993 (twenty-five years prior) with an Rpeak of 131.0 GFLOPS.[8]

Architecture and operating systems

In June 2016, a Chinese computer made the top based on SW26010 processors, a new, radically modified, model in the Sunway (or ShenWei) line.

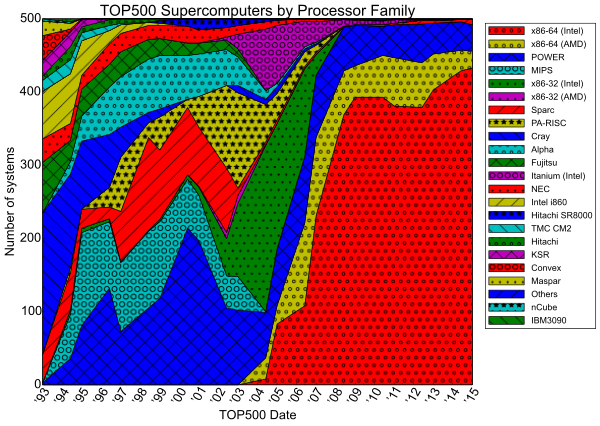

As of June 2018, TOP500 supercomputers are now all 64-bit, mostly based on x86-64 CPUs (Intel EMT64 and AMD AMD64 instruction set architecture), with few exceptions (all based on reduced instruction set computing (RISC) architectures) including 15 supercomputers based on Power Architecture used by IBM POWER microprocessors, six SPARC (all with Fujitsu-designed SPARC-chips, one of which—the K computer—surprisingly made the top in 2011 without a GPU, currently ranked 16th, while only dropping to 3rd on the HPCG list[9]), and two, seemingly related, Chinese designs: the ShenWei-based (ranked 11 in 2011, ranked 158th in November 2016) and Sunway SW26010-based ranked 1 in 2016, making up the remainder (another non-US design is PEZY-SC, while it is an accelerator paired with Intel's Xeon). Before the ascendance of 32-bit x86 and later 64-bit x86-64 in the early 2000s, a variety of RISC processor families made up most TOP500 supercomputers, including RISC architectures such as SPARC, MIPS, PA-RISC, and Alpha.

In recent years heterogeneous computing, mostly using Nvidia's graphics processing units (GPU) as coprocessors, has become a popular way to reach a better performance per watt ratio and higher absolute performance; it is almost required for good performance and to make the top (or top 10), with some exceptions, such as the mentioned SPARC computer without any coprocessors. An x86-based coprocessor, Xeon Phi, has also been used.

All the fastest supercomputers in the decade since the Earth Simulator supercomputer have used operating systems based on Linux. Since November 2017, all the listed supercomputers (100% of the performance share) use an operating system based on the Linux kernel.[10][11]

Since November 2015, no computer on the list runs Windows. In November 2014, Windows Azure[12] cloud computer was no longer on the list of fastest supercomputers (its best rank was 165 in 2012), leaving the Shanghai Supercomputer Center's Magic Cube as the only Windows-based supercomputer on the list, until it also dropped off the list. It had been ranked 436 in its last appearance on the list released in June 2015, while its best rank was 11 in 2008.[13]

It has been well over a decade since MIPS-based systems (meaning used as host CPUs) dropped entirely off the list[14] but the Gyoukou supercomputer that jumped to 4th place in November 2017 (after a huge upgrade) has MIPS as a small part of the coprocessors. Use of 2,048-core coprocessors (plus 8× 6-core MIPS, for each, that "no longer require to rely on an external Intel Xeon E5 host processor"[15]) make the supercomputer much more energy efficient than the other top 10 (i.e. it is 5th on Green500 and other such ZettaScaler-2.2-based systems take first three spots).[16] At 19.86 million cores, it is by far the biggest system: almost double that of the best manycore system in the TOP500, the Chinese Sunway TaihuLight, currently ranked 2nd.

Top 500 ranking

Legend:

- Rank – Position within the TOP500 ranking. In the TOP500 list table, the computers are ordered first by their Rmax value. In the case of equal performances (Rmax value) for different computers, the order is by Rpeak. For sites that have the same computer, the order is by memory size and then alphabetically.

- Rmax – The highest score measured using the LINPACK benchmarks suite. This is the number that is used to rank the computers. Measured in quadrillions of floating point operations per second, i.e., petaFLOPS.

- Rpeak – This is the theoretical peak performance of the system. Measured in PFLOPS.

- Name – Some supercomputers are unique, at least on its location, and are thus named by their owner.

- Model – The computing platform as it is marketed.

- Processor – The instruction set architecture or processor microarchitecture.

- Interconnect – The interconnect between computing nodes.

- Vendor – The manufacturer of the platform and hardware.

- Site – The name of the facility operating the supercomputer.

- Country – The country in which the computer is located.

- Year – The year of installation or last major update.

- Operating system – The operating system that the computer uses.

Other rankings

Top countries

Numbers below represent the number of computers in the TOP500 that are in each of the listed countries.

| Country | Systems |

|---|---|

| China | 206 |

| United States | 124 |

| Japan | 36 |

| United Kingdom | 22 |

| Germany | 21 |

| France | 18 |

| Netherlands | 9 |

| Korea, South | 7 |

| Ireland | 7 |

| Canada | 6 |

| Australia | 5 |

| India | 5 |

| Italy | 5 |

| Poland | 4 |

| Russia | 4 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4 |

| Switzerland | 3 |

| Sweden | 3 |

| Singapore | 2 |

| Spain | 2 |

| South Africa | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Country | Jun 2018[20] | Nov 2017[21] | Jun 2017[22] | Jun 2016[23] | Nov 2015[24] | Jun 2015[25] | Nov 2014[26] | Jun 2014 | Nov 2013 | Jun 2013 | Nov 2012 | Jun 2012 | Nov 2011 | Jun 2011 | Nov 2010 | Jun 2010 | Nov 2009 | Jun 2009 | Nov 2008 | Jun 2008 | Nov 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 206 | 202 | 160 | 167 | 109 | 37 | 61 | 76 | 63 | 66 | 72 | 68 | 74 | 61 | 41 | 25 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 12 | 10 | |

| 124 | 143 | 168 | 165 | 199 | 233 | 231 | 233 | 264 | 252 | 250 | 252 | 263 | 255 | 276 | 280 | 277 | 291 | 291 | 258 | 284 | |

| 93 | 86 | 99 | 94 | 95 | 124 | 111 | 98 | 98 | 91 | 94 | 102 | 95 | 107 | 123 | 136 | 137 | 137 | 148 | 166 | 138 | |

| 36 | 35 | 33 | 29 | 37 | 40 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 35 | 30 | 26 | 26 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 22 | 20 | |

| 22 | 15 | 17 | 12 | 18 | 29 | 30 | 23 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 24 | 38 | 44 | 43 | 45 | 52 | 47 | 49 | |

| 21 | 21 | 28 | 26 | 33 | 37 | 26 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 30 | 25 | 47 | 31 | |

| 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 27 | 30 | 27 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 29 | 26 | 23 | 26 | 34 | 17 | |

| 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| 7 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 9 | |

| 5 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 6 | |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 7 | |

| 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||||

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 |

Systems ranked No. 1 since 1976

- IBM Summit (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- NRCPC Sunway TaihuLight (National Supercomputing Center in Wuxi

- NUDT Tianhe-2A (National Supercomputing Center of Guangzhou

- Cray Titan (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- IBM Sequoia Blue Gene/Q (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- Fujitsu K computer (Riken Advanced Institute for Computational Science

- NUDT Tianhe-1A (National Supercomputing Center of Tianjin

- Cray Jaguar (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- IBM Roadrunner (Los Alamos National Laboratory

- IBM Blue Gene/L (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- NEC Earth Simulator (Earth Simulator Center

- IBM ASCI White (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- Intel ASCI Red (Sandia National Laboratories

- Hitachi CP-PACS (University of Tsukuba

- Hitachi SR2201 (University of Tokyo

- Fujitsu Numerical Wind Tunnel (National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan

- Intel Paragon XP/S140 (Sandia National Laboratories

- Fujitsu Numerical Wind Tunnel (National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan

- TMC CM-5 (Los Alamos National Laboratory

- NEC SX-3/44 (

- Fujitsu VP2600/10 (

- Cray Y-MP/832 (

- Cray-2 (

- Cray X-MP (

- Cray-1 (

Number of systems

By number of systems as of June 2018:[27]

|

Note, all operating systems of the TOP500 systems use Linux, but Linux above is generic Linux.

|

New developments in supercomputing

In November 2014, it was announced that the United States was developing two new supercomputers to exceed China's Tianhe-2 in its place as world's fastest supercomputer. The two computers, Sierra and Summit, will each exceed Tianhe-2's 55 peak petaflops. Summit, the more powerful of the two, will deliver 150–300 peak petaflops.[28] On 10 April 2015, US government agencies banned selling chips, from Nvidia, to supercomputing centers in China as "acting contrary to the national security... interests of the United States";[29] and Intel Corporation from providing Xeon chips to China due to their use, according to the US, in researching nuclear weapons – research to which US export control law bans US companies from contributing – "The Department of Commerce refused, saying it was concerned about nuclear research being done with the machine."[30]

On 29 July 2015, President Obama signed an executive order creating a National Strategic Computing Initiative calling for the accelerated development of an exascale (1000 petaflop) system and funding research into post-semiconductor computing.[31]

In June 2016, Japanese firm Fujitsu announced at the International Supercomputing Conference that its future exascale supercomputer will feature processors of its own design that implement the ARMv8 architecture. The Flagship2020 program, by Fujitsu for RIKEN plans to break the exaflops barrier by 2020 (and "it looks like China and France have a chance to do so and that the United States is content – for the moment at least – to wait until 2023 to break through the exaflops barrier."[32]) These processors will also implement extensions to the ARMv8 architecture equivalent to HPC-ACE2 that Fujitsu is developing with ARM Holdings.[32]

Inspur has been one of the largest HPC system manufacturer based out of Jinan, China. As of May 2017, Inspur has become the third manufacturer to have manufactured 64-way system – a record which has been previously mastered by IBM and HP. The company has registered over $10B in revenues and have successfully provided a number of HPC systems to countries outside China such as Sudan, Zimbabwe, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela. Inspur was also a major technology partner behind both the supercomputers from China, namely Tianhe-2 and Taihu which lead the top 2 positions of Top500 supercomputer list up to November 2017. Inspur and Supermicro released a few platforms aimed at HPC using GPU such as SR-AI and AGX-2 in May 2017.[33]

Large machines not on the list

Some major systems are not listed on the list. The largest example is the NCSA's Blue Waters which publicly announced the decision not to participate in the list[34] because they do not feel it accurately indicates the ability for any system to be able to do useful work.[35] Other organizations decide not to list systems for security and/or commercial competitiveness reasons. Additional purpose-built machines that are not capable or do not run the benchmark were not included, such as RIKEN MDGRAPE-3 and MDGRAPE-4.

Computers and architectures that have dropped off the list

IBM Roadrunner[36] is no longer on the list (nor is any other using the Cell coprocessor, or PowerXCell).

Although Itanium-based systems reached second rank in 2004,[37][38] none now remain.

Similarly (non-SIMD-style) vector processors (NEC-based such as the Earth simulator that was fastest in 2002[39]) have also fallen off the list. Also the Sun Starfire computers that occupied many spots in the past now no longer appear.

The last non-Linux computers on the list – the two AIX ones – running on POWER7 (in July 2017 ranked 494rd and 495th[40] originally 86th and 85th), dropped off the list in November 2017.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to TOP500. |

References

- ↑ A. Petitet, R. C. Whaley, J. Dongarra, A. Cleary (24 February 2016). "HPL – A Portable Implementation of the High-Performance Linpack Benchmark for Distributed-Memory Computers". ICL – UTK Computer Science Department. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Huang, Echo. "This is how dramatically China's beating the US in its share of supercomputers". Quartz.

- ↑ "An Interview with Jack Dongarra by Alan Beck, editor in chief HPCwire". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- 1 2 "Statistics on Manufacturers and Continents".

- ↑ "The TOP25 Supercomputer Sites". Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Where does Asia stand? This rising supercomputing power is reaching for real-world HPC leadership". Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Rpeak – This is the theoretical peak performance of the system. Measured in PFLOPS.

- ↑ "Sublist Generator". Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ "HPCG - June 2018 | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ↑ "Top500 – List Statistics". Top500.org. November 2017.

- ↑ "Linux Runs All of the World's Fastest Supercomputers". The Linux Foundation. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ↑ "Microsoft Windows Azure".

- ↑ "Magic Cube – Dawning 5000A, QC Opteron 1.9 GHz, Infiniband, Windows HPC 2008".

- ↑ "ORIGIN 2000 195/250 MHz | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ↑ "PEZY-SC2 - PEZY". Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ↑ "The 2,048-core PEZY-SC2 sets a Green500 record". WikiChip Fuse. 2017-11-01. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

Powering the ZettaScaler-2.2 is the PEZY-SC2. The SC2 is a second-generation chip featuring twice as many cores – i.e., 2,048 cores with 8-way SMT for a total of 16,384 threads. [..] The SC incorporated two ARM926 cores and while that was sufficient for basic management and debugging its processing power was inadequate for much more. The SC2 uses a hexa-core P-Class P6600 MIPS processor which share the same memory address as the PEZY cores, improving performance and reducing data transfer overhead. With the powerful MIPS management cores, it is now also possible to entirely eliminate the Xeon host processor. However, PEZY has not done so yet.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2018.

- 1 2 "China Tops Supercomputer Rankings with New 93-Petaflop Machine – TOP500 Supercomputer Sites".

- ↑ ABCI. "ABCI". AI Bridging Cloud Infrastructure. National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST). Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2018.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2017.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2017.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2016.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2015.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2015.

- ↑ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2014.

- ↑ "List Statistics". Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ Balthasar, Felix. "US Government Funds $425 million to build two new Supercomputers". News Maine. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "Nuclear worries stop Intel from selling chips to Chinese supercomputers". CNN. 2015-04-10. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ "US nuclear fears block Intel China supercomputer update".

- ↑ Executive Order -- Creating a National Strategic Computing Initiative (Executive order), The White House – Office of the Press Secretary, 29 July 2015

- 1 2 Morgan, Timothy Prickett. "Inside Japan's Future Exascale ARM Supecomputer". The Next Platform. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Supermicro, Inspur, Boston Limited Unveil High-Density GPU Servers | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- ↑ Blue Waters Opts Out of TOP500 (article), 16 November 2012

- ↑ Kramer, William, Top500 versus Sustained Performance – Or the Ten Problems with the TOP500 List – And What to Do About Them. 21st International Conference On Parallel Architectures And Compilation Techniques (PACT12), 19–23 September 2012, Minneapolis, MN, US

- ↑ "Roadrunner – BladeCenter QS22/LS21 Cluster, PowerXCell 8i 3.2 GHz / Opteron DC 1.8 GHz, Voltaire Infiniband". Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Thunder – Intel Itanium2 Tiger4 1.4GHz – Quadrics". Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Columbia – SGI Altix 1.5/1.6/1.66 GHz, Voltaire Infiniband". Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Japan Agency for Marine -Earth Science and Technology". Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "IBM Flex System p460, POWER7 8C 3.550GHz, Infiniband QDR". TOP500 Supercomputer Sites.

External links

- Official website

- LINPACK benchmarks at TOP500