Symmetry of second derivatives

In mathematics, the symmetry of second derivatives (also called the equality of mixed partials) refers to the possibility under certain conditions (see below) of interchanging the order of taking partial derivatives of a function

of n variables. If the partial derivative with respect to is denoted with a subscript , then the symmetry is the assertion that the second-order partial derivatives satisfy the identity

so that they form an n × n symmetric matrix. This is sometimes known as Schwarz's theorem, Clairaut's theorem, or Young's theorem.[1][2]

In the context of partial differential equations it is called the Schwarz integrability condition.

Hessian matrix

This matrix of second-order partial derivatives of f is called the Hessian matrix of f. The entries in it off the main diagonal are the mixed derivatives; that is, successive partial derivatives with respect to different variables.

In most "real-life" circumstances the Hessian matrix is symmetric, although there are a great number of functions that do not have this property. Mathematical analysis reveals that symmetry requires a hypothesis on f that goes further than simply stating the existence of the second derivatives at a particular point. Schwarz' theorem gives a sufficient condition on f for this to occur.

Formal expressions of symmetry

In symbols, the symmetry says that, for example,

This equality can also be written as

Alternatively, the symmetry can be written as an algebraic statement involving the differential operator Di which takes the partial derivative with respect to xi:

- Di . Dj = Dj . Di.

From this relation it follows that the ring of differential operators with constant coefficients, generated by the Di, is commutative. But one should naturally specify some domain for these operators. It is easy to check the symmetry as applied to monomials, so that one can take polynomials in the xi as a domain. In fact smooth functions are possible.

Schwarz's theorem

In mathematical analysis, Schwarz's theorem (or Clairaut's theorem on equality of mixed partials)[3] named after Alexis Clairaut and Hermann Schwarz, states that if

has continuous second partial derivatives at a given point in , say, then

The partial differentiations of this function are commutative at that point. One easy way to establish this theorem (in the case where , , and , which readily entails the result in general) is by applying Green's theorem to the gradient of

Sufficiency of twice-differentiability

A weaker condition than the continuity of second partial derivatives (which is implied by the latter) which suffices to ensure symmetry is that all partial derivatives are themselves differentiable.[4] Another strengthening of the theorem, in which existence of the permuted mixed partial is asserted, was provided by Peano:

If is defined on an open set and exist everywhere on , and is continuous at , then exists at and .[5]

History

The result of the equality of the mixed partial derivatives under certain conditions has a long history. Nicolaus I Bernoulli implicitly assumed the result as early as 1721, but Euler was the first to provide a proof. Other proofs followed by Clairaut (1740), Lagrange (1797), Cauchy (1823) and many others in the 19th century. None of these proofs were without fault however (for example, Clairaut assumed all definite integrals could be differentiated under the integral sign). In 1867 Ernst Leonard Lindelöf published a paper[6] criticizing in detail all the proofs he was familiar with. Finally, six years later Hermann Schwarz (1873) gave the first satisfactory proof. This was followed by successive refinements that relaxed the hypotheses in Schwarz's theorem in various ways, among others by Dini, Jordan, Peano, E. W. Hobson, W. H. Young. For a good historical account, see.[7]

Distribution theory formulation

The theory of distributions (generalized functions) eliminates analytic problems with the symmetry. The derivative of an integrable function can always be defined as a distribution, and symmetry of mixed partial derivatives always holds as an equality of distributions. The use of formal integration by parts to define differentiation of distributions puts the symmetry question back onto the test functions, which are smooth and certainly satisfy this symmetry. In more detail (where f is a distribution, written as an operator on test functions, and φ is a test function),

Another approach, which defines the Fourier transform of a function, is to note that on such transforms partial derivatives become multiplication operators that commute much more obviously.

Requirement of continuity

The symmetry may be broken if the function fails to have differentiable partial derivatives, which is possible if Clairaut's theorem is not satisfied (the second partial derivatives are not continuous).

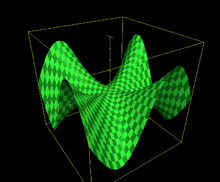

An example of non-symmetry is the function

-

(1)

This function is everywhere continuous, but its derivatives at (0,0) cannot be computed algebraically. Rather, the limit of difference quotients shows that , so the graph z = f(x,y) has a horizontal tangent plane at (0,0), and the partial derivatives exist and are everywhere continuous. However, the second partial derivatives are not continuous at (0,0), and the symmetry fails. In fact, along the x-axis the y-derivative is , and so:

In contrast, along the y-axis the x-derivative , and so . That is, at (0, 0), although the mixed partial derivatives do exist, and at every other point the symmetry does hold.

The above function, written in a cylindrical coordinate system, can be expressed as

showing that the function oscillates four times when traveling once around an arbitrarily small loop containing the origin. Intuitively, therefore, the local behavior of the function at cannot be described as a quadratic form, and the Hessian matrix thus fails to be symmetric.

In general, the interchange of limiting operations need not commute. Given two variables near (0, 0) and two limiting processes on

corresponding to making h → 0 first, and to making k → 0 first. It can matter, looking at the first-order terms, which is applied first. This leads to the construction of pathological examples in which second derivatives are non-symmetric. This kind of example belongs to the theory of real analysis where the pointwise value of functions matters. When viewed as a distribution the second partial derivative's values can be changed at an arbitrary set of points as long as this has Lebesgue measure 0. Since in the example the Hessian is symmetric everywhere except (0,0), there is no contradiction with the fact that the Hessian, viewed as a Schwartz distribution, is symmetric.

In Lie theory

Consider the first-order differential operators Di to be infinitesimal operators on Euclidean space. That is, Di in a sense generates the one-parameter group of translations parallel to the xi-axis. These groups commute with each other, and therefore the infinitesimal generators do also; the Lie bracket

- [Di, Dj] = 0

is this property's reflection. In other words, the Lie derivative of one coordinate with respect to another is zero.

Application to differential forms

The Clairaut-Schwarz theorem is the key fact needed to prove that for every (or at least twice continuously differentiable) differential form , the second exterior derivative vanishes: . This implies that every exact form (i.e., a form such that for some form ) is closed (i.e., ), since .[8]

References

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2006. Retrieved 2015-01-02.

- ↑ Allen, R. G. D. (1964). Mathematical Analysis for Economists. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 300–305.

- ↑ James, R. C. (1966). Advanced Calculus. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ↑ Hubbard, John; Hubbard, Barbara. Vector Calculus, Linear Algebra and Differential Forms (5th ed.). Matrix Editions. pp. 732–733.

- ↑ Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 235–236. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

- ↑ Lindelöf, Ernst Leonard (1867). "Remarques sur les différentes manières d'établir la formule ". Acta Societatis Scientiarum Fennicae. 8, part 1: 205–213.

- ↑ Higgins, Thomas James (1940). "A note on the history of mixed partial derivatives". Scripta Mathematica. 7: 59–62. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ↑ Tu, Loring W. (2010). An Introduction to Manifolds (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7399-3.

Further reading

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Partial derivative", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4