Swakopmund

| Swakopmund | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

.jpg) Close-up aerial photo of Swakopmund | ||

| ||

| Motto(s): Providentiae memor | ||

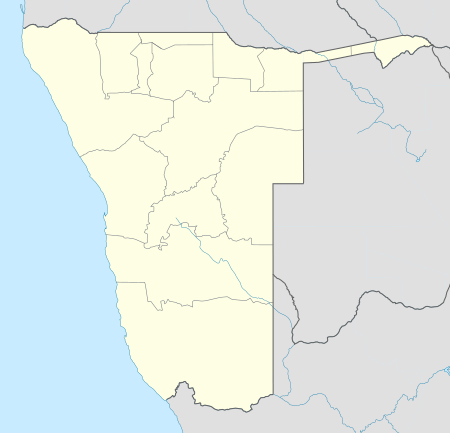

Swakopmund Location in Namibia | ||

| Coordinates: 22°41′S 14°32′E / 22.683°S 14.533°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Region | Erongo | |

| Constituency | Swakopmund Constituency | |

| Founded | August 4, 1892 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Paulina Ndahafa Nashilundo | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 196.3 km2 (75.8 sq mi) | |

| Population (2011)[2][1] | ||

| • Total | 44,725 | |

| • Density | 227.8/km2 (590/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) | |

| Climate | BWk | |

| Website |

swakop | |

Swakopmund (German for "Mouth of the Swakop") is a city[3] on the coast of western Namibia, 352 km (219 mi) west of the Namibian capital Windhoek via the B2 main road. It is the capital of the Erongo administrative district. The town has 44,725 inhabitants and covers 196 square kilometres (76 sq mi) of land.[1][4] The city is situated in the Namib Desert and is the fourth largest population centre in Namibia.

Swakopmund is a beach resort and an example of German colonial architecture. It was founded in 1892 as the main harbour for German South West Africa, and a small part of its population is still German-speaking today.

.jpg)

Buildings in the city include the Altes Gefängnis prison, designed by Heinrich Bause in 1909. The Woermannhaus, built in 1906 with a prominent tower (Damara tower), is now a public library. Attractions in Swakopmund include a Swakopmund Museum,[5] the National Marine Aquarium, a crystal gallery and spectacular sand dunes near Langstrand south of the Swakop River. Outside the city, the Rossmund Desert Golf Course is one of only five all-grass desert golf courses in the world. Nearby is a farm that offers camel rides to tourists and the Martin Luther steam locomotive, dating from 1896 and abandoned in the desert.

Swakopmund lies on the B2 road and the Trans-Namib Railway from Windhoek to Walvis Bay. It is served by Swakopmund Airport and Swakopmund Railway Station.

Etymology

The Herero called the place Otjozondjii.[6] The name of the town is derived from the Nama word Tsoakhaub ("excrement opening") describing the Swakop River in flood carrying items in its riverbed, including dead animals, into the Atlantic Ocean. However, Prof. Peter Raper, Honorary Professor: Linguistics, at the University of the Free State points out that the name for Swakopmund is based on the San language, namely from “xwaka” (rhinoceros) and “ob” (river).[7] The German settlers changed it to Swachaub, and when in 1896 the district was officially proclaimed, the version Swakopmund (German: Mouth of the Swakop) was introduced.[8]

History

Captain Curt von François founded Swakopmund in 1892 as the main harbour for the Imperial German colony—The deep sea harbour at Walvis Bay belonged to the British. The founding date was on August 8 when the crew of gunboat Hyäne erected two beacons on the shore. Swakopmund was chosen for its availability of fresh water, and because other sites further north such as Cape Cross were found unsuitable. The site did, however, not offer any natural protection to ships lying off the coast, a geographical feature not often found along Namibia's coast.[8]

When the first 120 Schutztruppe soldiers and 40 settlers were offloaded at Swakopmund, they had to dig caves into the sand for shelter. The offloading was done by Kru tribesmen from Liberia who used special boats. Woermann-Linie, the operator of the shipping route to Germany, employed 600 Kru at that time.[8]

Swakopmund quickly became the main port for imports and exports for the whole territory, and was one of six towns which received municipal status in 1909. Many government offices for German South West Africa had offices in Swakopmund. During the Herero Wars a concentration camp for Herero people was operated in town. Inmates were forced into slave labour; approximately 2,000 Herero died.

Soon, the harbour created by the "Mole" (breakwater) silted up, and in 1905 work was started on a wooden jetty, but in the long run this was inadequate. In 1914 construction of a steel jetty was therefore commenced, the remains of which can still be seen today. After the First World War it became a pedestrian walkway. It was declared structurally unsound and was closed to the public for seven years, and in 2006 renovations to the portion supported by concrete pillars were completed, with a seafood restaurant and sushi bar being added to the end portion of the steel portion of the jetty soon after. A new timber walkway was also added onto the existing steel structure, and the steel portion of the jetty reopened to the public in late 2010.

Trading and shipping companies founded branches in Swakopmund. A number of these buildings still exist today. After German South West Africa was taken over by the Union of South Africa in 1915, all harbour activities were transferred from Swakopmund to Walvis Bay. Many central government services ceased. Businesses closed down, the number of inhabitants diminished, and the town became less prosperous. However, the natural potential of Swakopmund as a holiday resort was recognised, and this potential has subsequently been developed. Today tourism-related services form an important part of the town's economy.

After Namibian independence from South Africa in 1990 many street names were changed from their original German, or in some cases, Afrikaans names, to honour Namibians, predominantly Namibians of black heritage. For example, in 2001, then-president of Namibia Sam Nujoma renamed the main street (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Straße) Sam Nujoma Avenue in honour of himself.[9]

Politics

Swakopmund is governed by a municipal council that has ten seats.[10]

Namibia's ruling SWAPO party won the 2010 local authority election with 4,496 votes, followed by the local Swakopmund Residents Association (SRA, 1,005 votes), the United Democratic Front (UDF, 916 votes), the Rally for Democracy and Progress (RDP, 666 votes), and the National Unity Democratic Organisation (NUDO, 280 votes).[11] The 2015 local authority election was again won by SWAPO which gained six seats (5,534 votes). One seat each was won by the UDF (1,168 votes), the SRA (790 votes), the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA, 497 votes), and NUDO (296 votes).[12]

Administrative divisions

There are the following districts and suburbs in Swakopmund:

- Town Centre

- Vineta

- Meile 4

- Vogelstrand

- Waterfront

- Mondesa

- Tamariskia

- Democratic Resettlement Community

- The Democratic Resettlement Community is an informal settlement in Swakopmund. It was founded in 2001 as temporary housing for people waiting for subsidized housing in the city.[13]

Most inhabitants of the town live in the suburbs of Vineta, Tamariskia, Mondesa and Vogelstrand. Both black and white people, mostly well-to-do, live in Vineta. Tamariskia was originally a neighbourhood for the coloured people, built in the early 1970s, to replace the shacks the coloureds earlier had between the town centre and Vineta. Mondesa existed already in the 1960s, and it was a neighbourhood for the black people, and it was a considerable distance from the town centre in the early days.

Economy and infrastructure

Mining

The discovery of uranium at Rössing, 70 km (43 mi) outside the town, led to the development of the world's largest opencast uranium mine. This had an enormous impact on all facets of life in Swakopmund which necessitated expansion of the infrastructure of the town to make it into one of the most modern in Namibia.

Tourism

_Swakopmund%2C_aerial_view_2017.jpg)

The city has scattered coffee shops, night clubs, bars and hotels. There are balloon rides, skydiving, quad biking, as well as small marine cruises. The Swakopmund Skydiving Club has operated from Swakopmund Airport since its founding in 1972.

In August 2008, filming commenced in Swakopmund on the AMC television series The Prisoner starring Jim Caviezel and Sir Ian McKellen. Swakopmund was used as the film location for The Village.[14]

In May 2015, Hollywood production company Village Roadshow Pictures commenced filming of Mad Max: Fury Road, featuring Charlize Theron and Tom Hardy, in and around Swakopmund and the surrounding desert landscapes.[15]

Technology

In October 2000, an agreement was signed between the Namibian and People's Republic of China governments to build a satellite tracking station at Swakopmund. Construction was completed in July 2001 at a site north of Swakopmund to the east of the Henties Bay-Swakopmund road and opposite the Swakopmund Salt Works. The site was chosen as it was on the orbital track of a manned spacecraft during its re-entry phase. Costing N$12 million, the complex covers 150m by 85m. It is equipped with five metre and nine metre satellite dishes.

Public health

The main healthcare provider in the city is the Cottage Medi-Clinic, a hospital with 70 beds.[16]

Geography

Climate

| Swakopmund | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Surrounded by the Namib Desert on three sides and the cold Atlantic waters to the west, Swakopmund enjoys a mild desert climate (BWn, according to the Köppen climate classification). The average temperature ranges between 15 °C (59 °F) to 25 °C (77 °F). Rainfall is less than 20 mm per year, making gutters and drainpipes on buildings a rarity. The cold Benguela current supplies moisture for the area in the form of fog that can reach as deep as 140 km (87 mi) inland. Fogs that originate offshore from the collision of the cold Benguela Current and warm air from the Hadley Cell create a fog belt that frequently envelops parts of the Namib desert. Coastal regions can experience more than 180 days of thick fog a year.[17][18] While this has proved a major hazard to ships—more than one thousand wrecks litter the Skeleton Coast—it is a vital source of moisture for desert life. The fauna and flora of the area have adapted to this phenomenon and now rely upon the fog as a source of moisture.

Education

The German school Regierungsschule Swakopmund was previously located in the city.[19]

Notable people

- Rosina ǁHoabes, former Mayor

- Werner Schulz (footballer)

- Razundara Tjikuzu, former professional footballer, played in the German Bundesliga for Werder Bremen (1998-2003), Hansa Rostock (2003–05) MSV Duisburg (2005–06) before going on to play in the Turkish Super League

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 "Table 2.1 Population density by area" (PDF). 2011 Population and Housing Census - Erongo Regional Profile. Namibia Statistics Agency. p. 4. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Table 4.2.2 Urban population by Census years (2001 and 2011)" (PDF). Namibia 2011 - Population and Housing Census Main Report. Namibia Statistics Agency. p. 39. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Local Authorities". Association of Local Authorities in Namibia (ALAN). Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ "ELECTIONS 2010: Erongo regional profile". New Era. 16 November 2010.

- ↑ "Swakopmund Museum". Scientific Society Swakopmund. Retrieved 2017-12-17.

- ↑ Menges, Werner (12 May 2005). "Windhoek?! Rather make that Otjomuise". The Namibian.

- ↑ [Dictionary of Southern African Place Names by Dr P.E. Raper]

- 1 2 3 "Swakopmund". namibweb.com. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Barnard, Maggi (12 December 2002). "Namibia: Minister Urges Swakopmund Residents to Accept Change" – via AllAfrica.

- ↑ "Know Your Local Authority". Election Watch (3). Institute for Public Policy Research. 2015. p. 4.

- ↑ "Press Release Local Authority – Erongo – Swakopmund". Electoral Commission of Namibia. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Local elections results". Electoral Commission of Namibia. 28 November 2015. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015.

- ↑ Swakop’s DRC to provide for youth February 13, 2008, The Namibian

- ↑ "The Prisoner". AMC website. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Williams, Sue (14 May 2015). "How Australia got magnificently replaced in Mad Max".

- ↑ "Our Hospitals". cottagemc.co.za.

- ↑ Goudie, Andrew (2010). "Chapter 17: Namib Sand Sea: Large Dunes in an Ancient Desert". In Migoń, Piotr. Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 163–169. ISBN 978-90-481-3054-2.

- ↑ Spriggs, Amy. "Namib desert (AT1315)". Wild World. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ↑ "Deutscher Bundestag 4. Wahlperiode Drucksache IV/3672" (Archive). Bundestag (West Germany). 23 June 1965. Retrieved on 12 March 2016. p. 32/51.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swakopmund. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Swakopmund. |