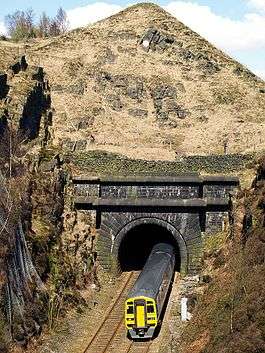

Summit Tunnel

Summit Tunnel in England is one of the world's oldest railway tunnels. It was constructed between 1838 and 1841 by the Manchester and Leeds Railway Company to provide a direct line between Leeds and Manchester. When built, Summit Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel in the world.

The tunnel, between Littleborough and Walsden near Todmorden, was bored beneath the Pennines, a natural obstruction to most forms of traffic. The tunnel is just over 1.6 miles (2.6 km) long and carries two standard-gauge tracks in a single horseshoe-shaped tube, approximately 7.2 metres (24 ft) wide and 6.6 metres (22 ft) high. Summit Tunnel was designed by the civil engineer Thomas Longridge Gooch, assisted by Barnard Dickinson. Progress on the tunnel’s construction was slower than anticipated, largely because the excavation process was more difficult than anticipated. On 1 March 1841, Summit Tunnel was officially opened by Sir John Frederick Sigismund Smith; it had cost of £251,000 and 41 workers had lost their lives.

On 20 December 1984, the Summit Tunnel fire occurred. No lives were lost and five months later, the tunnel reopened after limited repair work. The tunnel has remained in continuous use for passenger and freight services with little interruption since it opened.

Development

Summit Tunnel, between Littleborough and Todmorden[1] is the highest section of the 51 miles (82 km) long Manchester and Leeds Railway, which was built parallel to the Rochdale Canal. When built, it was the world’s longest railway tunnel and a critical element of the first trans-Pennine line to be established.[1]

The tunnel was designed by the civil engineer Thomas Longridge Gooch, a close collaborator with the pioneering railway engineer George Stephenson and his son Robert Stephenson on several railway ventures.[1] Between spring 1835 and 1844, Gooch was the acting engineer to the Manchester and Leeds Railway Company on behalf of George Stephenson, who was working on other projects. During September 1837, during Gooch’s tenure, work commenced boring the tunnel.[1] Gooch was assisted on its construction by Barnard Dickinson. When speaking about the tunnel, Dickinson exclaimed: "This tunnel will defy the rage of tempest, fire, war or wasting age".[2]

The tunnel has a length of 2,638 metres (2,885 yd) and a height of 6.6 metres (22 ft); the horseshoe-shaped structure is 7.9 metres (26 ft) wide and accommodates a pair of tracks. It was driven by hand through shale, coal and sandstone, after which the walls were lined with six courses of brick, using in excess of 23 million bricks.[3] The bricks were handmade locally and up to 60,000 were laid in a single day.[1] Mortar, commonly referred to as Roman cement, was used for its impermeability to water. It has been estimated that around 8,100 tonnes (dry weight) of cement was transported to the tunnel from Hull.[1] During August 1838, James Wood, the chairman of the Manchester and Leeds Railway, laid the first brick of the tunnel in a ceremony.[1]

The original contractors were Evans, Stewart and Copeland.[1] At the peak of construction, a workforce of between 800 and 1,250 men and boys was active on site, aided by around 100 horses and 13 stationary steam engines, which were used for removing material out of the shafts.[1] The bedrock was hewn using a combination of physical strength and hand tools, illuminated only by candlelight. At an early stage of the track laying process, the rails were laid directly onto excavated rock, but it was decided use more conventional wooden sleepers instead.[1] The extracted rocks were used for other purposes, including in the construction of sections of the Blackpool Promenade.[1]

Alignment of the tunnel was achieved by drilling of fourteen vertical shafts to provide survey points above.[1] When the tunnel was complete, two shafts were sealed and the remaining twelve were retained as blast relief shafts, used to vent steam and smoke produced by locomotives passing through the tunnel. The 14 ventilation shafts were up to 28 to 94 metres (92 to 308 ft) deep. During the tunnel's service life, No.6 was sealed after rock falls.[1]

Progress on the tunnel’s construction has been slower than expected; the bedrock and blue shale through which it was bored proved to be harder to excavate than anticipated.[1] During March 1839, as a result of the project’s slow progress, the original contractors were dismissed and George Stephenson took over, after which the pace of work increased until a strike amongst the tunnel’s bricklayers occurred during March 1840.[2] The last brick was laid on 9 December 1840.[1]

Summit Tunnel should have opened on New Year’s Eve 1840; but the opening was delayed after the discovery of a defective invert, located 0.5 miles (0.8 km) from one end of the tunnel, which had displaced the central track drain. Following remedial action, the tunnel was officially opened by Sir John Frederick Sigismund Smith, the government inspector of railways, on 1 March 1841. Summit Tunnel was completed at a cost of £251,000,and the loss of 41 lives.[1] The cost was far in excess of what the Manchester and Leeds Railway Company had expected.[2]

The tunnel has remained in continuous use for passenger and freight services since it opened. Monitoring movements within the tunnel is currently achieved via track circuits, specifically Ebi Track 400 system track circuits.

Incidents

The tunnel closed for the first eight months of 1985 following a fire that generated sufficient heat as to vitrify sections of the tunnel’s outer brickwork.[1][2] The build up of heat in the surrounding ground led to the phenomenon of a 'false spring'; many plants produced flowers and buds as the warm soil triggered a period of new growth. Damage to the tunnel lining was minimal which was attributed to heated gases from the fire escaping through the ventilation shafts.[2] Restorative work involved replacing 500 metres (550 yd) of track and sleepers before it re-opened to traffic on 19 August 1985.[1][4]

On 28 December 2010, a passenger train travelling from Manchester to Leeds was derailed when it struck a large amount of ice that had fallen onto the tracks from one of the ventilation shafts. The ice had built up during a period of exceptionally cold weather and fell into the tunnel when it started to thaw. The train was the first to use the tunnel in three days as a result of a temporary break in services around Christmas. The train collided with the tunnel wall, but remained upright and no injuries were reported.[5][6]

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 “Summit Tunnel.” ‘’engineering-timelines.com’’, Retrieved: 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thacker, Simon. "The Summit tunnel 175 years on: The miracle of engineering which survived a devastating fire." Manchester Evening News, 28 February 2018.

- ↑ The Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales, vol. 3, p. 20. Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1851.

- ↑ "Summit Tunnel blaze was a threat to towns' future." Todmorden News, 19 December 2009.

- ↑ “Derailment in Summit tunnel, near Todmorden, West Yorkshire.” ‘’Rail Accident Investigation Board’’, 2012.

- ↑ "Derailment in Summit tunnel, near Todmorden, West Yorkshire, 28 December 2010." Office of Rail Regulation, 13 October 2014.

Further reading

- MacDonald, M. The World From Rough Stones (1975, Random House); a novel set during the building of the Summit Tunnel.

External links

![]()