Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc.

| Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 31, 2016 Decided March 22, 2017 | |

| Full case name | Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., et al. |

| Docket nos. | 15–866 |

| Citations |

580 U.S. ___ (more) 137 S. Ct. 1002; 197 L. Ed. 2d 354; 2017 U.S. LEXIS 2026 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Prior history |

|

| Subsequent history | Case settled over Star Athletica's objection (2017) |

| Holding | |

| Aesthetic design elements on useful articles like clothing can be copyrightable if they can be separately identified as art and exist independently of the useful article. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Thomas, joined by Roberts, Alito, Sotomayor, Kagan |

| Concurrence | Ginsburg |

| Dissent | Breyer, joined by Kennedy |

| Laws applied | |

| Copyright Act of 1976 (17 U.S.C. § 101) | |

Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. ___ (2017), was a Supreme Court of the United States case in which the Court decided under what circumstances aesthetic elements of "useful articles" can be restricted by copyright law. The Court created a two-prong "separability" test, granting copyrightability on conditions of separate identification and independent existence. In other words, the aesthetic elements must be identifiable as art if mentally separated from the article's practical use and must qualify as copyrightable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works if expressed in any medium.

The case concerned a dispute between two clothing manufacturers, Star Athletica and Varsity Brands. Star Athletica began creating cheerleading uniforms with stripes, zigzags, and chevron insignia similar to some made by Varsity, produced at a far lower price point. Varsity sued Star Athletica for copyright infringement and Star Athletica claimed the clothing designs were uncopyrightable because their aesthetic designs were tied so closely to and guided by their utilitarian purposes as uniforms. The Court rejected this argument with a close reading of the statute and established that the clothing designs, as aesthetic elements of the useful article of clothing, could be copyrightable. The Court had declined to hear Star Athletica's follow-up question concerning whether Varsity's specific designs were original enough to be copyrightable, so that part of the case remained unaddressed and Varsity's copyright registrations stood.

The Court's conclusion that aesthetic elements of useful articles, and thereby clothing design elements, could be copyrighted excited fashion designers and intellectual property scholars. Some loved the decision because they saw extending copyright to clothes as parity with other creative industries that had enjoyed copyrights for much longer. Others denounced the Court's opinion over ambiguities in how to enforce the new rules and because of its potential to end fashion trends in generic clothing.

Background

Historical copyrightability and Varsity Brands

At one time, clothing designs were not subject to copyright law, or "uncopyrightable," in the United States. In 1941, the Court heard Fashion Originators' Guild of America v. FTC, which considered the fashion industry's practice of boycotting sale of their "high fashion" works at places that would sell knock-offs made by other companies for lower prices, so-called "style piracy". The court ruled against the Guild, saying that this practice of attempting to create a monopoly outside of the copyright system suppressed free competition and violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.[1] However, outside fashion, Mazer v. Stein established in 1954 that an artistic statue created to adorn a lamp base could be copyrightable separately from the utilitarian lamp under expansions from the Copyright Act of 1909. The statue's mass-production alongside the lamp did not invalidate that.[2]

Another barrier to copyrightability in the United States is a certain vague threshold of originality that must be met to be eligible for an intellectual property monopoly like a copyright or patent. In 1964's Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. Stiffel Co., the Court agreed with a lower court's ruling that Stiffel's popular lamp design was not original enough to warrant a patent preventing the lamp's sale by Sears, rescinding that restriction and passing the design to the public domain. The Court's opinion indicated that the same logic would apply to an inappropriate copyright.[3]

In the Copyright Act of 1976, Congress changed the copyright law to allow copyrighting aesthetic features of "useful articles,"[4] or "an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information."[5] This move was intended to better incorporate the Mazer v. Stein ruling[4][6] while clarifying the difference between the copyrightability of "applied art" and the more traditional, lesser restriction of "industrial design," the overall combination of features, provided by design patents or trade dress. The Act said "pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features" of useful articles were copyrightable only if "separable" from the utilitarian aspects of the design and capable of existing independently of the article.[7] This broad definitional language lead to a proliferation of about ten competing, inconsistent legal tests for that separability,[4][8][9] a state of affairs criticized for appearing to have judges serve as art critics.[4]

Because clothes have both aesthetic and utilitarian features in their designs, they fall under this useful article category; therefore, the shapes and cuts of clothing are not copyrightable. Designs placed on clothing were opened up to the possibility of copyrightability, subject to those tests.[4] Practically, the law was construed to mean that copyrighted two-dimensional designs could be placed on clothing, and fabric pattern sheets could be copyrighted before being cut to make clothing, but an article of clothing's overall color scheme and design could not be copyrighted because it was not capable of existing independently of the final useful article.[10] Some fashion designers bristled under these rules, wondering why other creative industries like films or music were allowed to restrict access to their products with copyright and they were not.[11][12][13] Others interpreted fashion's successes as an industry thriving in the absence of copyright, perhaps in part because of that.[14][15][16] Congresspeople introduced several bills over the years to outright remove the separability requirement from the law, but none of these were successfully signed into law.[17]

Nonetheless, Varsity Brands, the largest cheerleading and sports uniform manufacturer in the world,[18][19] could not register copyrights for the designs of their cheerleading uniforms as clothing. Instead, Varsity applied for copyrights on drawings and photographs of those designs[7][20] as "two-dimensional artwork" or "fabric design (artwork)." That design represented in the images would then be applied to the clothing via sewing or sublimation, a process where designs are printed on paper, placed on the fabric, and then heated so the ink sinks in.[21] Following rejections from the Copyright Office, Varsity described the uniforms in extremely specific detail to make the registration appear limited, improving their registration chances. The Office approved[7] over 200[22] of these narrowly-defined copyrights with descriptions like "has a central field of black bordered at the bottom by a gray/white/black multistripe forming a shallow 'vee' of which the left-hand leg is horizontal, while the right-hand leg stretches 'northeast' at approximately a forty-five degree angle." Varsity proceeded to frequently file lawsuits alleging infringement via accusations of very general copying,[7] intended to stop other companies from releasing competing uniforms. Those competitors regarded these lawsuits as frivolous because the claimed designs were so simple.[23]

Star Athletica lawsuit

Star Athletica was founded in January 2010 as a subsidiary of The Liebe Company. Varsity Brands accused Star Athletica of being created in retaliation for Varsity cancelling a deal with The Liebe Company's sports lettering subsidiary, aided by former Varsity employees knowledgeable about Varsity designs. Later that year,[23] Varsity Brands filed suit against Star Athletica for infringing five of its copyrighted designs for cheerleading uniforms.[24] The Star Athletica designs were not exactly identical, physically or graphically, but Varsity's general description of allegedly copied elements in court filings, "the lines, stripes, coloring, angles, V’s [or chevrons], and shapes and the arrangement and placement of those elements," suited both designs and the case moved forward.[7] Varsity also sued for trademark infringement under the Lanham Act[4] and Star Athletica counter-sued Varsity under the Sherman Antitrust Act for allegedly monopolizing the cheerleading industry,[25] but these portions of the case were dismissed.[4][25]

In 2014, the United States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee ruled Star Athletica's favor on the grounds that the designs were not eligible for copyright restriction. According to Judge Robert Hardy Cleland, a design without the distinctive marks like chevrons and zigzags would not identifiable as cheerleading uniforms, so the designs were not separately identifiable. They were not conceptually separable because the marks, if viewed outside the context of the clothing, would have still evoked the idea of a cheerleading uniform.[4][26][27]

The district court's decision was reversed on appeal by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit with the majority of Judge Karen Nelson Moore joined by Judge Ralph B. Guy Jr.. Firstly, Moore said the district court should have deferred to the fact that the Copyright Office's trained personnel had granted the copyright registrations in the first place. On the questions of the case, Moore evaluated the competing separability tests, but ended up creating a new five-step test for the Circuit's analysis. In short, they found that the designs were copyrightable because the clothes had the utility of being athletic wear and removing the designs did not affect that utility. She said the design could be separately identifiable because it could be held "side by side" with a blank dress and there would be no utilitarian difference, and it could certainly exist independently because the individual aspects like chevrons could appear in designs on other clothing items. Moore also said that a ruling in favor of Star Athletica would have rendered all paintings uncopyrightable because they decorated the rooms where they hung. Judge David McKeague dissented because of a disagreement over the application of one of the test's steps. The third step asked the court to determine the useful article's "utilitarian aspects." Instead of the majority's more general assessment of athletic wear, McKeague would have defined the uniforms as clothing the body "in an attractive way for a special occasion" and "identify[ing] the wearer as a cheerleader;" therefore, the aesthetic features could not be separated from the utilitarian to him.[4][28]

Star Athletica filed to be heard by the United States Supreme Court in January 2016. On May 2, 2016 the Court granted certiorari "to resolve widespread disagreement over the proper test for implementing § 101's separate-identification and independent-existence requirements." Star Athletica also wanted the Court to decide if Varsity's specific designs were sufficiently original to be copyrighted, but the Court declined.[29]

Amicus curiae

The case attracted the attention of various interest groups that filed fifteen briefs of amicus curiae.[30] Among the Star Athletica's advocates was Public Knowledge, which helped draft a brief representing the views of costuming groups, particularly cosplayers of the Royal Manticoran Navy and the International Costuming Guild, who were concerned that a ruling in Varsity's favor could endanger their craft, as much of it involved recreating recognizable designs from pop culture.[31][32] The Royal Manticoran Navy filed a separate supporting brief that emphasized fair use rights in costuming while voicing a concern that allowing clothing design copyrights would worsen[33][34] a common characterization of Varsity Brands as a monopolist of the cheerleading industry with 80% market share.[18][34][35][36][37] Public Knowledge was also involved in a brief representing the views of Shapeways, the Open Source Hardware Association, Formlabs, and the Organization for Transformative Works. They worried that copyright restriction would impact 3D printing by making it difficult to share designs and by creating a fiscal incentive for media companies to crack down on derivative works.[15][38][39] Another group of supporters, styled "Intellectual Property Professors," objected to broadly expanding copyright to useful article designs because they considered design patents sufficient and because of specific examples of what Congress considered copyrightable when drafting the 1976 law. In their view, copyrighting the uniform designs would unduly stretch Congress's intent to copyright minor detailing on industrial designs like floral engravings on silverware, carvings in the backs of chairs, or prints on t-shirts.[40]

Varsity received an endorsement from the Council of Fashion Designers of America, which believed that extending copyright to clothing designs was critical to prevent exploitative copyists and preserve the United States's rapid rate of expansion in the worldwide fashion industry, representing $370 billion in domestic consumer spending and 1.8 million jobs.[13][23] The Fashion Law Institute shared these interests and advised that a decision to copyright clothing designs would be a proper reading of the Mazer v. Stein ruling's later incorporation in the 1976 Copyright Act.[33][41] Both criticized the "fast-fashion" industry of duplicating expensive designs with increasingly-cheap 3D printing technology without paying the original creators.[13][41] The Institute spoke highly of "geek fashion," including cosplay, as a burgeoning part of the industry rife with copyrightable expression.[41] The United States government also supported Varsity. In part, the government claimed that the question of a proper separability analysis was unnecessary because, in creating the designs as drawings, Varsity had received a copyright for them and reserved the exclusive ability to reproduce that design however they chose in any medium. They pointed to a concession from Star Athletica that if, hypothetically, Varsity controlled The Starry Night, Varsity would be able to restrict the printing of the painting on dresses.[42] Star Athletica had conceded this because it was an abstract painting, not a design for a dress,[35] but the United States made the point that the painting would cover the entire dress surface—no different than the Varsity designs. The government also argued that, in applying the requested conceptual separability analysis, what mattered was that a uniform stripped of the design "remain[ed] similarly useful" when compared to the original. A blank dress was equivalent to a designer dress, so the design was copyrightable in the eyes of the government.[42]

Oral arguments

Oral argument convened on October 31, 2016, Star Athletica represented by John J. Bursch and Varsity by William M. Jay. Eric Feigin also spoke on Varsity's behalf, representing the United States as amicus curiae.[43][44][45]

Star Athletica's lawyers gave the Court examples of how the graphic designs were utilitarian. For instance, the colors and shapes were arranged to create optical effects like the Müller-Lyer illusion and deliberately change the cheerleader's appearance to make them appear taller, thinner, and generally more appealing. They considered this distinct from applying a pre-existing two-dimensional image to the uniform because the lines required for those illusions to function needed to be properly located on properly fitted uniforms.[43] According to them, people often made those sorts of deliberately utilitarian decisions about their clothing to make themselves look better or happier.[46] Moreover, were those designs placed on another object, such as a lunchbox, they would not be serving that utilitarian purpose anymore.[47] Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in particular, rejected that line of argument, citing the fact that the examples presented in evidence were two-dimensional works. In her view, it did not matter that the submitted designs were "superimposed" on three-dimensional uniforms—the designs were submitted in two-dimensional images, so the designs were separated from the uniforms and copyrightable. After all, both parties agreed that the physical, three-dimensional uniform's cut and how it physically framed the body was not copyrightable. They were interested in the colors and aesthetic designs that were applied to the useful article.[46] She was not comfortable with vagueness she perceived in how Star Athletica wanted the Court to decide when a given two-dimensional design "is what makes an article utilitarian" when that design could conceivably be placed on anything.[48] Chief Justice John Roberts felt much the same and added that the designs did more than sit practically on the body because they sent a "particular message" that distinguished it from a blank dress, namely that the wearer was "a member of a cheerleading squad." Receiving this expression leaned him toward thinking of it as copyrightable expression.[46]

The members of the Court also considered more abstract aspects of the case. For example, it was unclear how a decision in Varsity's favor might affect military-style camouflage patterns and whether or not they could be restricted if fashion designs were copyrightable. Varsity supported the idea of camouflage copyrights, although Justice Elena Kagan pointed out the clear utilitarian function of camouflage patterns: concealment. On the industry side, women's fashion alone was a concern worth hundreds of billions of dollars worldwide. Justice Stephen Breyer speculated that the price of dresses could conceivably double if copyright terms were applied to designs and knock-off brands couldn't compete at lower prices.[46] Justice Sonia Sotomayor and he questioned Varsity over their concerns of monopolization effects, such as a uniform design becoming part of a school's brand identity and compelling them to buy exclusively from Varsity during a century of copyright restriction. In the end, Breyer expressed worry that designers or lawyers might resort to simply copyrighting drawings to sue over the design of any dress or suit.[48] Sotomayor, formerly a representative of Fendi in cases brought against knock-offs, wondered aloud if a decision for Varsity would destroy those knock-offs brands, although she was not sure if that would be a bad thing.[20] Justice Anthony Kennedy wondered whether it was "the domain of copyright to [restrict] the way people present themselves to the world."[48]

Breyer also got attention in the media for his aphorism about the purpose of fashion, "The clothes on the hanger do nothing; the clothes on the woman do everything." Kagan thought the sentiment was "so romantic."[20][43][46]

Opinion of the Court

Majority opinion

Justice Clarence Thomas delivered the majority opinion, which was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Alito, Sotomayor, and Kagan.[4] The Court defined its task as "whether the lines, chevrons, and colorful shapes appearing on the surface of [Varsity Brands'] cheerleading uniforms are eligible for copyright restriction as separable features of the design of those cheerleading uniforms."[49] The Court did not consider whether the designs in the case actually met copyright restriction's threshold of originality.[50] Thomas rejected arguments from Varsity and the United States that separability analysis was unneeded,[51] but also did away with all the lower court tests used previously. Instead, the opinion provided one canonical two-part test based on the statute and the Mazer v. Stein decision:[52]

...an artistic feature of the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work either on its own or in some other medium if imagined separately from the useful article.[53]

After applying this test to the cheerleading uniforms, the Court ruled in Varsity's favor that the designs were separable from the useful article and could be copyrighted.[50][54] The separability analysis started with the admittedly permissive first requirement, identifying the designs as separately identifiable "pictoral, graphical, or sculptural works." The design needed to be able to exist independently, and Thomas concluded that the design did when it appeared in other media, such as the two-dimensional drawings submitted to the Copyright Office. In Thomas's view, this conceptual separation would not necessarily recreate the useful dress because the design's elements like the chevrons could appear on items in different contexts,[50][55] and they did not conjure uniform even when that context was other items of clothing.[54] This analysis moved the consideration away from whether the item left after separation was useful, to solely whether or not the design itself was useful. A feature incapable of being separated was a utilitarian feature anyway, Thomas said.[50][55]

Addressing concerns that this would grant control over more than the design, Thomas pointed out that the separated aesthetic element could not, itself, be a useful article. Someone also couldn't copyright a design and then exert control over its physical representation. A drawing a or small model of a car, copyrighted, could not restrict production of the functional automobile with the same body by a competitor. The car drawing would not suppress a rival car manufacturer in the automobile market, so Varsity's uniform drawing would not suppress Star Athletica in the uniform market because their uniforms could have the same cut.[55]

The final section of the opinion discussed objections to the decision raised by the parties in their briefs. There were no requirements that there be an equivalent useful article remaining after the design element was conceptually removed or that the removed element be "solely artistic." Thomas said discussions of the blank dress were unnecessary because the statute did not require the remaining work to be useful or "similarly useful," as the government had put it, because all that mattered was if the separated element was a pictorial, graphical, or sculptural work. Thomas said that adopting this requirement would have overruled Mazer because the reason the statue in that case was considered "applied art" was because the 1909 Act had removed an earlier distinction between aesthetic and useful works of art. That distinction was not reinstated by the 1976 Act, so there was to be no distinguishing between "conceptual" and "physical" separability.[56]

Thomas further rejected Star Athletica's additional "objective" considerations from preexisting tests, namely that the work be identified as artistic contributions from a designer independent of the utilitarian purpose, and that the work still be marketable without the utilitarian function of the design.[50][57] These were not within the statute, so Thomas dismissed them, saying that all that mattered was consumer perception and not the design's intent. Finally, regarding the idea that Congress's noted reluctance to apply copyrightability to useful articles in general, Thomas said that congressional inaction was usually not a significant argument with courts. Thomas found a lot of the discussion moot because copyright could not restrict the cut of the design and copyright coverage was not mutually exclusive from design patenting.[57]

Concurrence

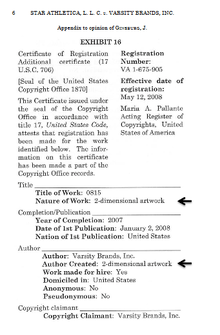

Justice Ginsburg wrote an opinion concurring in judgement—the cheerleading uniform designs were separable—without joining in the majority's reasoning. The copyrights were not registered for the useful articles of clothing, emphasized Ginsburg. The registrations were for pictoral and graphical works that were then reproduced on the clothing.[4][58] Because the Copyright Act of 1976 provided copyright claimants "the right to reproduce the work in or on any kind of article, whether useful or otherwise,"[59] the claimant of a pictorial, graphical, or sculptural work's copyright could restrict others from reproducing the work's elements on their separate useful articles. According to her, there was no need for the court to address the separability analysis issue at all.[4][60] To prove her point, Justice Ginsburg attached to her decision several pages of applications submitted by Varsity Brands to the Copyright Office, pointing to their claimed type of work being "2-dimensional artwork" or "fabric design (artwork)."[61]

In the concurrence's notes, Ginsburg mentioned that she also did not take a stand on whether or not Varsity's designs were actually original enough to be copyrightable. Nonetheless, she did refer to a previous case called Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co. and quoted its conclusion that "the requisite level of creativity [for copyrightability] is extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice."[62]

Dissent

Justice Breyer, joined by Justice Kennedy, dissented. While he agreed with much of the majority's reasoning, he disagreed with the framing and application of the majority's test and concluded the design was not separable from the uniform's useful article.[63] Breyer also criticized what he considered vagueness in the majority's test. He thought that, under it, "virtually any industrial design" could be considered separable as soon as it was thought of in terms of art, whether via giving it a picture frame or merely calling the object art like a Marcel Duchamp series.[4][64] Breyer's approach to the problem was to interpret what "identified separately" meant in the context of the statute. His reading was that, to be separable, the design features needed to be either physically separable from the article while leaving the utilitarian object functional or else the design features needed to be conceivably separable without conjuring a picture of the utilitarian object in someone's mind. He returned to Mazer v. Stein and applied his reasoning to two lamps, one with a Siamese cat statuette for a pole and one with an brass rod pole and a cat statuette attached elsewhere on its base. When it was elsewhere on the base, it could be physically separable and was therefore copyrightable as a figurine. When the cat was the pole, it couldn't be physically separated, but it could be conceptually separated from the context of the lamp without conjuring the idea of a lamp and was therefore copyrightable as a figurine.[65] Applying his version of the test to the cheerleader uniforms, he found that the design was not physically separable. Further, picturing the design separately would reveal a cheerleader uniform "coextensive with that design and cut", so the design and useful article were not conceptually separable either.[50][63][66]

He then considered shoes painted by Vincent van Gogh and turned to the examples of Congress's intended targets of copyright in the amicus curiae brief filed by the Intellectual Property Professors. Breyer found that copyrighting those embellishments was not the same as copyrighting an entire cheerleading uniform design because those examples were conceptually separable while the uniform design was not. He reiterated that van Gogh could certainly have received a copyright to prevent people from reproducing his creative painting, but the request in Star Athletica was an injunction against creating uniforms and Breyer felt this decision would be equivalent to giving van Gogh a design copyright that could prevent other from producing those shoes.[67] He directly accused Varsity Brands of trying to acquire copyrights in order to "prevent its competitors from making useful three-dimensional cheerleader uniforms by submitting plainly unoriginal chevrons and stripes as cut and arranged on a useful article."[66]

The majority opinion believed Breyer's concerns were not a bar to a design's copyrightability, and neither was Star Athletica's similar idea that the design couldn't be copyrighted because the designs would have the same outline as the useful article. They analogized the uniform's design to a mural on a curved dome, saying that the contour of the dome would not prevent the mural from being copyrightable. They also thought that Breyer's traditional view that a preexisting two-dimensional artwork applied to a portion of the clothing could be copyrighted was contradictory because then the statute would provide copyright restriction to designs that covered part of the clothing surface, but not designs that covered all of it.[68] Ginsburg's concurrence agreed on the second point in its notes, and referred to the fact that portions of Varsity's claimed uniform designs do appear on other merchandise like t-shirts.[69]

Additionally, the dissenting justice studied the state of the fashion industry at the time of the decision. Recent Congresses had rejected 70 bills to extend copyright to cover designs on useful articles, which he interpreted as an unwillingness of lawmakers to enact the change. He cited the metrics provided by the Varsity amici Council of Fashion Designers of America to show that the fashion industry was doing very well for itself without copyright and quoted warnings from Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Babington Macaulay against wantonly expanding copyright monopolies. Seeing no pressing need to extend the restriction, he was not willing to overstep the bounds of the Constitution's Copyright Clause, especially when the available design patents afforded fifteen years of restriction and copyright could offer more than a century.[70]

Subsequent developments

Immediate reactions

Varsity Brands's leadership and supporters were pleased by the decision. Varsity founder Jeff Webb said that it was a win for "the basic idea that designers everywhere can create excellent work and make investments in their future without fear of having it stolen or copied." Susan Scafidi, founder of the Fashion Law Institute, had been involved in with the case from the district court level and lamented that it had to go all the way to the Supreme Court. Still, she praised Thomas's decision as a maintenance of the status quo based on the copyrightability of fabric patterns. Although it was important to her because she believed fashion designers deserved to restrict their valuable designs with copyright, she didn't think it would change things for designers because it was based on the language of the preexisting statute.[71][72]

On March 31, 2017,[73] Puma sued Forever 21 for a number of alleged violations of Puma's intellectual property rights. Puma based the copyright infringement portion of their case on the nine-day-old precedent and said that various Forever 21 shoes included copyrighted elements of similar Puma products. Forever 21, a supplier of knock-offs, had been sued for copyright infringement in the past, but this was among the first times that a company used the argument that, in the case of Puma's Fenty Fur Slides, their "wide plush fur strap extending to the base of the sandal" was capable of being represented in another tangible medium, and therefore covered by copyright as separable from the shoe itself. Puma claimed "a casually knotted satin bow with pointed endings atop a satin-lined side strap that extends to the base of the sandal" was a copyrighted element on their Bow Slides.[74][75]

The United States Copyright Office, arbiter of copyright registration, updated its Compendium of rules for validating registrations with preliminary rules taking the Star Athletica developments into account.[76] The new report, published September 29, 2017, reminded that useful articles[77] and, more specifically, clothing articles were not copyrightable.[78] Regarding two-dimensional visual designs applied to useful articles, the Compendium reduced its 2014 discussion of the copyrightability of various kinds designs with different kinds of useful article[79] to one section in the 2017 guide that quoted Star Athletica's two step separability test. There was a note indicating that the Office was "developing updated guidance" on the matter to be included in a future version of the report.[80]

Case resolution

The case was passed back to the district court in Tennessee and, in August 2017, the case was settled out of court in favor of Varsity Brands, over Star Athletica's objection, by Star Athletica's insurance company. Star Athletica wanted to press a counter-claim following the Supreme Court's ruling that designs on the uniforms could be copyrightable with an argument that the particular Varsity designs in the case should not be copyrightable due to their simplicity. The settlement precluded that argument and closed the case with prejudice, so the seven years of litigation concluded firmly.[81][82]

Legal analyses

Columbia Law School professor Ronald Mann provided an analysis of the opinion for SCOTUSblog, remarking:

What the court does not state expressly in that part of its opinion is that the standard for determining whether a graphic work (for example) is copyrightable is minimal. ... So once the court has said that any design can gain copyright protection if it would be protectable if placed first on a piece of paper, it really has ensured that all but the subtlest graphic designs will be able to gain copyright protection. ... To put [the Court's application of its test to the uniforms (quoted in the "majority opinion" section above)] more bluntly, once we determine that the designs 'hav[e] … graphic … qualities … [and could be] applied … on a painter’s canvas,' the test for copyrightability is met. ... I am sure that my colleagues who study intellectual property will write at length for years to come about the doctrinal nuances of the court’s discussion of the separability requirement, which seems to me a marked shift from most of the prior treatments.[83]

.jpg)

There was a split amongst intellectual property attorneys between those who thought the opinion clarified the law[21][71][84] and those who thought it made things more ambiguous.[7][85][86] Clear or not, many have noted that Star Athletica was an important case for the fashion industry because it overturned the prevailing wisdom that fashion designs were generally uncopyrightable. The effects of this shift in thought remains to be seen as more designers apply for copyrights and awareness of this change grows.[50][21] Particularly, there is speculation regarding negative effects on fashion trends, which involve some degree of copying basic styles among designers throughout the industry,[50][87][88][89] and anticipation of an increase in infringement lawsuits.[50] Generic or "knock-off" clothing could cease to exist entirely due to the restriction of the designer brands' designs,[21] although designer brands were also accused of copying independent artists before the decision.[90]

The Harvard Law Review felt Star Athletica was an important step towards removing subjectivity from the tests in this area of the law, such as by removing the framing problem that changed the outcome of the analysis based on how the usefulness of the article was defined, evidenced by Judge McKeague. However, the Review worried that the decision may not fully resolve conflicting lower court rulings because the conflicting majority and dissent were both based on close readings of the statute without enough clearly differentiating examples in the majority to completely discredit the alternative view. A potential contradiction in Thomas's majority opinion may not help on that front that pecerption; specifically, the assertion that surface designs are "inherently separable" from useful articles without being useful articles themselves and the assertion that other clothing bearing the design do not conjure the original useful article. The Review speculated that "these dicta imply that the independently existing work can have the shape and look of the article, evoke the same concepts, and even perform the same function and still be separable," and therefore be copyrightable.[4] Indeed, a 2018 disctrict court case, Silvertop Assocs., Inc. v. Kangaroo Mfg., Inc., ruled that a banana costume's physical features were separable from the costume and copyrightable because they could be painted on a canvas.[91]

Professors Jeanne C. Fromer and Mark P. McKenna were critical of the ambiguity of the decision because the three major stages of litigation resulted in three different majority decisions on three different grounds, with more divergent opinions among the dissents and concurrence. Because the courts allowed Varsity to define extremely narrow copyright restrictions in the registration then sue others like Star Athletica with general descriptions in court filings, they were concerned that this disconnect in requirements would lead to more controversial lawsuits, even outside the realm of useful articles. After all, a model car could be copyrighted as a sculpture, a drawing of that model could be copyrighted, and the claimant could use features of either equally to file copyright claims. Exactly what features of either were actually restricted was left up to debate because the registration's description could diverge almost entirely from the lawsuit's filing, so Fromer and McKenna contended it would be impossible to know what the copyright holder considered restricted before they described it in a lawsuit, let alone before the second party begins the desired copying. Moreover, in the absence of that description, they said it was impossible to perform a separability analysis and determine if the feature was even copyrightable at all before active litigation.[7]

Sara Benson, a lawyer who agreed with the decision, has wondered if the court's explicit rejection of a copyrightability test that valued artistic effort on the designer's part may harm perception of designers' value to the clients they work for. She mentioned that that test had allowed designers to leverage their creativity for respect and credibility during corporate design processes, and that its removal may have removed some of their negotiating power.[21]

David Kluft of Foley Hoag has noted that this new ability to copyright design elements comes paired with criminal penalties if it comes to light that the elements have any utility. If the entity applying for copyright on the design knew about that utility, that would be considered false representation of a material fact in the copyright registration.[92]

There's also some uncertainty over how this case law may impact the copyrightability of another class of useful articles: food.[93] Top chefs had been seeking this for years before Star Athletica,[94] some taking the step of prohibiting their customers from taking photographs of the food in the name of supposed copyright restriction.[95][96] The pre-Star Athletica interpretation of separability allowed one to argue the copyrightability of food as a sculpture with artistic features that didn't contribute to its purpose as a consumable.[95][94] James P. Flynn of Epstein Becker & Green wondered if Star Athletica might have changed the fate of served food.[93]

References

- ↑ Fashion Originators' Guild of America v. FTC, 312 U.S. 457 (1941)

- ↑ Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201 (1954)

- ↑ Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. Stiffel Co., 376 U.S. 225 (1964)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc". Harvard Law Review. 2017-11-04. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ↑ 17 U.S.C. § 101

- ↑ Robert Kastenmeier (1976-09-03). House of Representatives Report No. 94-1476 (PDF) (Report). United States House of Representatives. p. 105. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

Section 113 deals with the extent of copyright protection in "works of applied art." The section takes as its starting point the Supreme Court's decision in Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201 (1954), and the first sentence of subsection (a) restates the basic principle established by that decision.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fromer, Jeanne C.; McKenna, Mark P. (2018-05-30). "Claiming Design". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 167. SSRN 3186762.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Jane C. (2016-09-01). "'Courts Have Twisted Themselves into Knots': US Copyright Protection for Applied Art". The Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts. Rochester, NY. 40 (1). SSRN 2837728.

- ↑ Fisher, Daniel (2016-05-02). "Supreme Court Dives Into Copyright Fight Over Cheerleader Uniforms". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ "924.3(A) Clothing Designs". Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. December 22, 2014. p. 41. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

Clothing such as shirts, dresses, pants, coats, shoes, and outerwear are not eligible for copyright protection because they are considered useful articles. This is because clothing provides utilitarian functions, such as warmth, protection, and modesty.... Although the copyright law does not protect the shape or design of clothing...designs imprinted in or on fabric are considered conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of garments, linens, furniture, or other useful articles. Therefore, a fabric or textile design may be registered if the design contains a sufficient amount of creative expression.

- ↑ Kover, Amy (2005-06-19). "That Looks Familiar. Didn't I Design It?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Telfer, Tori (2013-09-03). "Fashion Designs Aren't Protected By Copyright Law, So Knockoffs Thrive as Designers Suffer". Bustle. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- 1 2 3 Brief of Council of Fashion Designers of America as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- ↑ Bollier, David; Racine, Laurie (2003-09-09). "Control of creativity? Fashion's secret". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- 1 2 Brief of Public Knowledge, the International Costumers Guild, Shapeways, Inc., the Open Source Hardware Association, Formlabs Inc., Printrbot Inc., the Organization For Transformative Works, the American Library Association, the Association of Research Libraries, and The Association of College and Research Libraries as Amici Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- ↑ Morning Edition (2012-09-10). "Why Knockoffs Are Good For The Fashion Industry". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Zarocostas, John (August 2018). "The role of IP rights in the fashion business: a US perspective". www.wipo.int. WIPO Magazine. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- 1 2 Reigstad, Leif (2015-07-21). "Varsity Brands Owns Cheerleading and Fights to Keep it From Becoming an Official Sport". Houston Press. Houston Press. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Kees, Laura A.; Shaw, Stephen (2017-03-24). ""Knock-Offs" Beware: SCOTUS Makes a Fashion-Forward Decision". National Law Review. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Robert (2016-10-31). "Supreme Court hears arguments in cases centering on cheerleading outfits and a goldendoodle service dog". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benson, Sara R. (2018). "Sports Uniforms and Copyright: Implications for Applied Art Educators from the Star Athletica Decision". Journal of Copyright in Education and Librarianship. 2 (1). doi:10.17161/jcel.v2i1.6575. ISSN 2473-8336. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 1.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Erin Geiger (2016-10-31). "Who Owns Cheerleader Uniform Designs? It's up to the Supreme Court". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 2 (quoting 2014 WL 819422, *8-*9 (WD Tenn., Mar. 1, 2014)).

- 1 2 Brief of the Respondents (Sep. 14, 2016), Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- ↑ Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, LLC (W.D. Tenn. Mar. 1, 2014). Text

- ↑ Tewarie, Shrutih V. (2014-04-30). "District Court Struggles With Copyright Protection For 'Cheerleading-Uniformness'". Mondaq. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, LLC (6th Cir. Aug. 19, 2015). Text

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 1; see also No. 15-866 (docket), United States Supreme Court (last visited April 15, 2017) ("May 2, 2016 Petition GRANTED limited to Question 1 presented by the petition.")

- ↑ No. 15-866 (Star Athletica docket), United States Supreme Court (last visited July 20, 2018)

- ↑ Brief of Public Knowledge, Royal Manticoran Navy, and International Costumer's Guild as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- ↑ Nicholas Datlowe, Cosplay Comes to SCOTUS on Halloween, Bloomberg BNA (October 27, 2016)

- 1 2 AFP Relax News (2016-10-31). "The Supreme Court Ponders Costumes and Copyright on Halloween". Yahoo. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- 1 2 Brief of Royal Manticoran Navy: The Official Honor Harrington Fan Association, Inc. as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- 1 2 Brief for the Petitioner, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- ↑ Pietz, Morgan E.; Maxim, Trevor (2017-04-01). "Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc". Gerard Fox Law. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Buchanan, Leigh (2016-02-22). "Meet Rebel Athletic, the $20 Million Custom Cheerleading Uniform Startup Living Up to Its Name". Inc.com. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Masnick, Mike (2016-07-26). "How A Supreme Court Case On Cheerleader Costumes & Copyright Could Impact Prosthetic Hands And Much, Much More". Techdirt. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Kramer, Alexis (2016-02-11). "3D Printing Industry Wants One Copyright Test, Not 10". Bloomberg BNA. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ Brief of Intellectual Property Professors as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- 1 2 3 Brief of Fashion Law Institute as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- 1 2 Brief of United States as Amicus Curiae, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017)

- 1 2 3 Walsh, Mark (2016-10-31). "A 'view' from the courtroom: Dress for success". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 1; see also No. 15-866 (docket), United States Supreme Court (last visited April 15, 2017) ("Oct 31 2016 Argued. For petitioner: John J. Bursch, Caledonia, Mich. For respondents: William M. Jay, Washington, D. C.; and Eric J. Feigin, Assistant to the Solicitor General, Department of Justice, Washington, D. C. (for United States, as amicus curiae.)")

- ↑ "Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc". Oyez. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Liptak, Adam (October 31, 2016). "In a Copyright Case, Justices Ponder the Meaning of Fashion". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- ↑ Balluck, Kyle (2016-10-31). "Justices weigh cheerleading uniform designs". TheHill. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- 1 2 3 Mann, Ronald (2016-11-01). "Argument analysis: Justices worry about 'killing knockoffs with copyright'". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Quinn, Gene; Brachmann, Steve (2017-03-22). "Copyrights at the Supreme Court: Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands". IPWatchdog. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 4-6.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 8-11.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 11.

- 1 2 Star Athletica, slip op. at 10.

- 1 2 3 Star Athletica, slip op. at 7-8.

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 12-15.

- 1 2 Star Athletica, slip op. at 15-17.

- ↑ Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., No. 15-866, 580 U.S. ___ (2017), slip op. at 1 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in judgment)

- ↑

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 2 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in judgment).

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 4-14 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in judgment).

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 2 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in judgment).

- 1 2 Star Athletica, slip op. at 1 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 6-7 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 2-4 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- 1 2 Star Athletica, slip op. at 11 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 4-6 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 11

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 2-3 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in judgment)

- ↑ Star Athletica, slip op. at 7-9 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

- 1 2 The Federalist Society (2018-03-23). Star Athletica: One Year Later.

- ↑ Mejia, Zameena. "The Supreme Court says the iconic American cheerleading uniform design is protected by copyright law". Quartz. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Docket for PUMA SE v. Forever 21, Inc., 2:17-cv-02523". CourtListener. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ↑ "Puma Files Patent, Copyright, Trade Dress Suit Against Forever 21 Over Rihanna Shoes". The Fashion Law. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ↑ Morrow, Loni; Hyman, Jonathan (2017-04-04). "Puma Treads New Territory Hitting Forever 21 with Copyright Allegations after the Supreme Court's Star Athletica Decision". Knobbe Martens Intellectual Property Law. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- ↑ Fiscal 2017 Annual Report (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. p. 12.

- ↑ "906.8 Functional and Useful Elements". Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ "311.1 Copyrightable Subject Matter". Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ "924–924.3(D)". Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ "924 Registration Requirements for the Design of a Useful Article". Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition (PDF) (Report). United States Copyright Office. 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ Freeman, Helene M. (2017-09-25). "Star Athletica: An Unsatisfying End". The Fashion Industry Law Blog. Phillips Nizer, LLP. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ↑ Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, LLC (W.D. Tenn. 2017). Text

- ↑ Mann, Ronald (2017-03-22). "Opinion analysis: Court uses cheerleader uniform case to validate broad copyright in industrial designs". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Hannon, David (2017-03-27). "Copyrightability Clarified for Designs of "Useful" Articles". Bejin Bieneman PLC. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Buccafusco, Christopher; Lemley, Mark A. (2018). "Functionality Screens". Virginia Law Review. SSRN 2888094.

- ↑ Menell, Peter S.; Yablon, Daniel (2017-09-12). "Star Athletica's Fissure in the Intellectual Property Functionality Landscape". University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online (116). SSRN 3036254.

- ↑ Chinlund, Gregory J.; Bolos, Michelle (2017-03-28). "Apart at the Seams – Copyright Protection for Apparel: Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc". Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Greenwald, Judy (2017-03-28). "High court fashion statement could lead to more lawsuits". Business Insurance. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Morran, Chris (2017-03-22). "Supreme Court's Ruling In Cheerleader Uniform Case Could Lead To Higher Prices For Clothing, Furniture". Consumerist. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Puglise, Nicole (2016-07-21). "Fashion brand Zara accused of copying LA artist's designs". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ↑ Silvertop Assocs., Inc. v. Kangaroo Mfg., Inc. (D.N.J. 2018-30-18) ("These features include: a) the overall length of the costume, b) the overall shape of the design in terms of curvature, c) the length of the shape both above and below the torso of the wearer, d) the shape, size, and jet black color of both ends, e) the location of the head and arm cutouts which dictate how the costume drapes on and protrudes from a wearer (as opposed to the mere existence of the cutout holes), f) the soft, smooth, almost shiny look and feel of the chosen synthetic fabric, g) the parallel lines which mimic the ridges on a banana in three-dimensional form, and h) the bright shade of a golden yellow and uniform color that appears distinct from the more muted and inconsistent tones of a natural banana. The Court finds that, if these features were separated from the costume itself and applied on a painter's canvas, it would qualify as a two-dimensional work of art in a way that would not replicate the costume itself."). Text

- ↑ Kluft, David (2018-04-24). "Star Athletica and the Expansion of Useful Article Protection: Copyright Office Permits Registration of Automotive Floor Liner". Trademark And Copyright Law. Foley Hoag, LLP. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- 1 2 Flynn, James P. (2017-09-19). "Will It Be Known As 'Michelin Star Athletica'?: Why The US Supreme Court May Have Given American Chefs A Reason To Cheer". ILN IP Insider. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- 1 2 Reed, Natasha (2016-06-21). "Eat Your Art Out: Intellectual Property Protection for Food". Trademark And Copyright Law. Foley Hoag, LLP. Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- 1 2 Herzfeld, Oliver. "Protecting Food Creations". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul (2006-03-24). "Can you copyright a dish?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

External links

- Text of Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc. (section), 580 U.S. ___ (2017) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Google Scholar Justia

- SCOTUSblog case page