Skellig Michael

| Native name: Sceilig Mhichíl | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Skellig Michael | |

Skellig Michael | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Area | 21.9 ha (54 acres)[1] |

| Highest elevation | 218 m (715 ft)[2] |

| Administration | |

|

Republic of Ireland | |

| County | Kerry |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

| Official name | Sceilg Mhichíl |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv |

| Reference | 757 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

Skellig Michael (Irish: Sceilig Mhichíl) (or the Great Skellig (Irish: Sceilig Mhór) is a twin-pinnacled crag situated 11.6 kilometres (7.2 mi) west of the Iveragh Peninsula in County Kerry, Ireland.[2] Its twin island, "Little Skellig" (Sceilig Bheag) is smaller and practically inaccessible, and is closed to the public. The Skellig Islands, along with some of the Blasket Islands, form the most westerly part of the Republic of Ireland.[3]

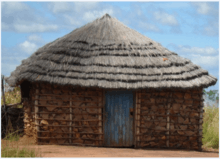

Skellig Michael consists of approximately 44 acres of rock, with its highest point, the Spit, 714 feet above sea level. It is known for its steep inhospitable landscape, the Gaelic monastery founded between the 6th and 8th century, and its variety of inhabiting species, including gannets, puffins, a colony of razorbills and a resident population of approximately fifty grey seals.[4] The rock contains the remains of a tower house, a megalithic stone row and a cross inscribed slab[5] known as the "Wailing Woman". The monastery is situated at 550–600 feet, while "Christ's Saddle" is 422 feet and the flagstaff area is 120 feet above sea level.[6] The island's slopes are ascended by a flight of stone steps. The remains of the monastery, which today consists of a small enclosure of beehive huts and oratories, and most of the island, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.[2] Because of the often difficult crossing from the mainland and the exposed nature of the small landing spot, the island is only accessible to the public during the summer months.

The name "Skellig" is derived from a Gaelic word for a splinter of stone (sceilig). Skellig Michael is named after the archangel Michael, said to have appeared there to help Saint Patrick banish serpents into the Irish sea.[7]

Geography and features

Skellig Michael is a steep rugged mass of rock (or "crag") of approximately c. 44 acres, located on the Atlantic coast the Iveragh peninsula of County Kerry. It is 7.25 miles west north west of Bolus Head, the southern end of Saint Finian's Bay. Its twin island, Little Skellig, is one mile closer to land, while the small Lemon Rock island is 2.25 miles further towards the coast.[6] The nearby Puffin Island hosts a variety of birds, including stormy petrel, guillemot, puffin and manx shearwater.[6]

The main landing cove is on the recesses of the eastern side. Known locally as "Blind Man's Cove",[8] it is exposed to sea swells and high waves, making approach difficult outside of summer months. The bay's pier is positioned under sheer cliff face, populated by high numbers of birds. It was built in 1826 and from an area known as the "Flagstaff", leads to a small stairway leading to the lighthouse. The steps split into two staircases, with the earliest and largely abandoned path leading directly to the monastery.[9]

The "Wailing Woman" rock is found low on the main ascent, below the "Christ's Saddle" ridge. The rock is located in the centre part of the island, 400 feet above sea level, and is situated on three acres of grassland. It is the only flat and fertile part of the island, and archaeologists have found traces of medieval crop farming. The path from the Saddle to the summit is known as the "Way of the Christ", a nomenclature reflecting the still present danger that such a steep climb presents to visitors.[10] Notable features on this stretch include the "Needle's Eye" peak,[9] a stone chimney 150 meters (490 feet) above sea level,[11] and a series of 14 stone crosses with names such as the "Rock of the Women's piercing caoine", further references to the harsh climb. Further up is the "stone of pain" area, including the station known as the "Spit", a long and narrow fragment of rock approached by two feet wide steps.[12] The ruin of the medieval church is lower and approached before the older monastery.[9]

Ecology

Skellig Michael has historically contained unusual seabird populations, now protected by the island's status as a nature reserve, owned by the state,[13] and its designation as an Important Bird Area and a Special Protection Area.

The Skellig islands were classified as a Special Protection Area in 1986.[14]

Birds of interest include Fulmar, Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), Storm petrel, Gannet, Kittiwake, Guillemot and Atlantic Puffin.

History

Pre-monastic

Except as an isolated location for temporary refuge, Skellig Michael was uninhabited before the founding of the Augustinian monastery,[2] and was used only for sanctuary and refuge. According to folklore, Ir, son of Míl Espáine, was buried on the island following a shipwreck c 1400 BC. Although from a prehistoric legend, the event appears in the Irish annals as the earliest extant record of the island:[15]

- Irr lost his life upon the western main;

- Skellig's high cliffs the hero's bones contain.

- In the same wreck Arranan too was lost,

- Nor did his corsp e'er touch Ierne's coast.[3]

Daire Domhain ("King of the World") is said to have stayed there c 200 AD before attacking Fionn mac Cumhaill's army in nearby Ventry.[15] A text from the 8th or 9th century records that Duagh, King of West Munster, fled to "Scellecc" after a feud with the Kings of Cashel sometime in the 5th century, although the historicity of the event has not been established.[16]

Monastic

The monastery's date of foundation is not known.[16] The first definite reference to monastic activity on the island is a record of the death of "Suibhini of Skelig" dating from the 8th century; however, Saint Fionán is claimed to have founded the monastery in the 6th century.[17] References in the Annals of the Four Masters record a number of events occurring at or around the Skelligs between the 9th and 11th centuries. Eitgall of Skellig, the monastery's Abbot, was taken by the Vikings in 823 and died of starvation thereafter. The Vikings again attacked in 838, sacking churches in Kenmare town, Skellig and Innisfallen Island. The Augustinian Abbey in Ballinskelligs was founded in 950, the same year that Blathmhac of Sceilig died. Finally, the annals mention the death of Aedh of Sceilig Michael, in 1040.[18]

The monastic site is positioned on a terraced shelf 600 feet (180 metres) above sea level, and developed between the sixth and eighth centuries. It contains six clochán-type beehive cells, two oratories, a number of stone crosses and slabs, and a later medieval church. The cells and oratories are all of dry-built corbel construction. A system for collecting and purifying water in cisterns was developed. It has been estimated that no more than twelve monks and an abbot lived here at any one time.[19] A hermitage is on the south peak.

The diet of monks living on the North Atlantic islands was somewhat different from that of those on the mainland. With less arable land available to grow grain, vegetable gardens were an important part of monastic life. Of necessity, fish and the meat and eggs of birds nesting on the islands were staples.[20]

The "Annals of Inisfallen" record a Viking attack in 823. The site had been dedicated to Saint Michael by at least 1044 (when the death of "Aedh of Scelic-Mhichí" is recorded).[1][16] However, this dedication may have occurred as early as 950, around which time a new church was added to the monastery (typically done to celebrate a consecration) and called Saint Michael's Church.[2]

The monastery was continuously occupied until the late 12th or early 13th century,[2] although it remained a site for pilgrimage through to the modern era. Theories for its abandonment include that the climate around Skellig Michael became colder and more prone to storms, Viking raids[21] and changes to the structure of the Irish Church. Probably a combination of these prompted the community to abandon the island and move to the abbey in Ballinskelligs.[16] The move was recorded by the Cambro-Norman Cleric and historian Giraldus Cambrensis during the end of the 12th century, when he wrote that the monks had moved to a new site on the continent".[22]

Post-monastic

Skellig Michael remained in the possession of the Catholic Canons Regular until the dissolution of the Ballinskelligs abbey during the Protestant Reformation by Elizabeth I in 1578.[2][23] Ownership was then passed to the Butler family with whom it stayed until the early 1820s, when the Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin (the predecessor to the Commissioners of Irish Lights) purchased the island for £500[24] from John Butler of Waterville in a compulsory purchase order.[16][23] The Corporation constructed two lighthouses on the Atlantic side of the island, and associated living quarters, all of which was completed by 1826.[1]

The Office of Public Works took the remains of the monastery into guardianship in 1880, before purchasing the island (with the exception of the lighthouses and associated structures) from the Commissioners of Irish Lights.[1][2][16]

Skellig Michael was made a World Heritage Site in 1996, at the 20th Session of the World Heritage Committee in Mérida, Mexico.[25] After being nominated for inclusion on 28 October 1995, an evaluation of the site by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (an advisory body of the World Heritage Committee), recommended that the island be inscribed on the basis of criteria (iii) and (iv) of the World Heritage List's selection criteria, which relate the cultural significance of a site.[23] The Committee approved this recommendation, describing Skellig Michael as of "exceptional universal value", and a "unique example of an early religious settlement", while also noting the site's preservation as a result of its "remarkable environment", and its ability to illustrate "as no other site can, the extremes of a Christian monasticism characterizing much of North Africa, the Near East and Europe".[25]

Several films have used the island as a filming location. The island was used as a filming location for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) and Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017).[26][27] It also served as a location for the final scene in Heart of Glass by Werner Herzog.[5]

Access

Each year at least four boat licences are granted to tour operators[28] who run trips to Skellig Michael during the summer season (May to October, inclusive), weather permitting. Even when conditions at the mainland are calm, the sea around the island itself can be turbulent. The area is a landing point for sea swells travelling in from distant depressions in the Atlantic. The island is lashed by water from all sides, with wave crests breaking at up to 10 metres over the pier and 45 metres along the lighthouse. When such large wave troughs recede, they can often expose ragged seaweed stumps, sponges and anemones on the rock faces, further hampering approach and landing.[4]

The local climate and exposed terrain makes crossing from the mainland to Skellig Michael difficult. Once landed the island's terrain is steep, unprotected and dangerous. The rock is ascended via 600 medieval stone steps leading towards the main island peak.[29] This remoteness and inaccessibility has long discouraged visitors, and so the island is exceptionally well preserved. Tourism began in the late 19th century, when a rowing boat could be hired for 25 shillings.[4] It did not become a popular tourist destination until the early 1970s when small chartered passenger boats become more frequent; five were available in 1973 at a price of £3 per person. By 1990 the level of demand had grown to the extent that the Office of Public Works began to organise ten boats departing from four individual harbours.[30]

A typical visit lasts about six hours. The Office of Public Works emphasises that the journey presents safety challenges. The steps do not contain grips, safety rails or barriers, and it is not recommended that children visit the island. The island does not include any visitor facilities, including water, shelter or bathrooms. Waterproof clothing and strong walking boots are recommended. Snacks, liquids and changes of clothes should be held in an over-shoulder carrier bag to allow the visitors' hands to be free for balance and safer walking the steep climb.[29]

For safety reasons, mainly because the steps are steep, rocky, old and unprotected, climbs are not permitted during wet or windy weather. Dive sites immediately around the rock, mostly around Blue Cove, are permitted in summer.[31]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Central Statistics Office. "CNA17: Population by Off Shore Island, Sex and Year". CSO.ie. Retrieved October 12, 2016. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Edward Bourke; Alan R. Hayden; Ann Lynch. "Skellig Michael Co. Kerry: the monastery and South Peak" (PDF). Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Retrieved 28 Dec 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). "Skellig Michael". UNESCO. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 1 2 S.M. (1913), p. 164

- 1 2 3 Lavelle (1976), pp. 31–32

- 1 2 O'Shea (1981), p. 28

- 1 2 3 O'Shea (1981), p. 3

- ↑ Lavelle (1976), pp. 11–12

- ↑ Lovegrove (2005), p. 156

- 1 2 3 O'Shea (1981), p. 8

- ↑ S.M. (1913), pp. 166–167

- ↑ Goldbaum, Howard. "Skellig Michael. Voices from the Distant Past. Retrieved 24 June 2018

- ↑ S.M. (1913), pp. 167

- ↑ "Skellig Michael". Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ "Skelligs SPA". National Parks & Wildlife Service.

- 1 2 Lavelle (1976), p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. "Skellig Michael: Historical Background". Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ↑ Lavelle (1976), 18

- ↑ S.B. (1913), 166

- ↑ "Holy Places – Skellig". Diocese of Kerry.

- ↑ Walter Horn, Jenny White Marshall, and Grellan D. Rourke (1990). "The Forgotten Hermitage of Skellig Michael". Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520064102.

- ↑ S.M. (1913), p. 165

- ↑ Lavelle (1976), p. 19

- 1 2 3 International Council on Monuments and Sites (October 1996). "World Heritage List: Skellig Michael" (PDF). International Council on Monuments and Sites. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ O'Shea (1981), p. 6

- 1 2 World Heritage Committee (10 March 1997). "Convention Concerning the World Cultural and Natural Heritage" (PDF). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. p. 68. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ↑ Siggins, Lorna (13 February 2016). "Concern over 'incidents' during 'Star Wars' filming on Skellig Michael". IrishTimes.com. Irish Times. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ National Monuments: Dáil Éireann Debate

- ↑ "Public Competition for a Permit to carry passengers to Skellig Michael" (PDF). HeritageIreland.ie. OPW.

- 1 2 "Visiting Skellig Michael – A Safety Guide". Office of Public Works, 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2018

- ↑ Lavelle (1976), 32

- ↑ "Diving around Skellig Michael". Ballinskelligs Watersports. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

Sources

- Lavelle, Des. The Skellig Story. Dublin: O'Brien Press, 1976. ISBN 789-0-8627-8882-7

- Lovegrove, Roger. Islands Beyond the Horizon: The life of twenty of the world's most remote places. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-1996-0649-8

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey. Sun Dancing: A Medieval Vision. Collins Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-8488-9004-6

- O'Shea, Tim. The Skelligs. Dublin: Irish Times, 1981

- S.M. "The Skelligs". Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Volume 2, No. 11, 1913

External links

- Visiting Skellig Michael – A Safety Guide – Office of Public Works, 2014

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skellig Michael. |

Coordinates: 51°46′16″N 10°32′26″W / 51.77111°N 10.54056°W