Sissinghurst Castle Garden

| Sissinghurst Castle Garden | |

|---|---|

"The most famous twentieth century garden in England."[1] | |

| Type | Garden |

| Location | Sissinghurst |

| Coordinates | 51°06′57″N 0°34′53″E / 51.1157°N 0.5815°ECoordinates: 51°06′57″N 0°34′53″E / 51.1157°N 0.5815°E |

| Architect | Vita Sackville-West / Harold Nicolson |

| Governing body | National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Sissinghurst Castle | |

| Designated | 1 May 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000181 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: West Range at Sissinghurst Castle | |

| Designated | 9 June 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1346285 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Tower and Walls 30 yards East of the West Range at Sissinghurst Castle | |

| Designated | 9 June 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1084163 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: The Priest's House at Sissinghurst Castle | |

| Designated | 20 June 1967 |

| Reference no. | 1346286 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: The South Cottage | |

| Designated | 20 June 1967 |

| Reference no. | 1084164 |

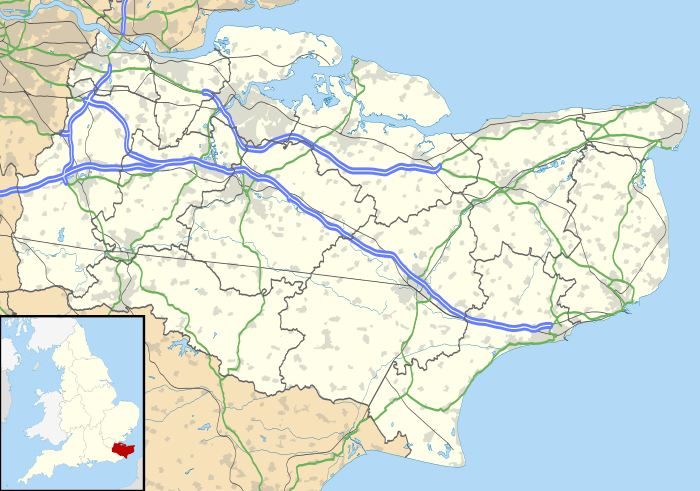

Location of Sissinghurst Castle Garden in Kent | |

Sissinghurst Castle Garden, at Sissinghurst in the Weald of Kent, England was created in the early 1930s by Vita Sackville-West, poet and gardening writer, and her husband Harold Nicolson, author and diplomat. It is among the most famous gardens in England and is designated a Grade I listed structure. The garden comprises a series of "rooms", amounting to ten in number, and was one of the earliest examples of this gardening style. Over seventy years after Vita and Harold created "a garden where none was",[2] Sissinghurst remains a major influence on horticultural thought and practice.

The origins of the present castle remains are a house begun in the 1530s by Sir John Baker and expanded by him c.1550. Construction was continued by his son Richard, who inherited in 1558. Richard constructed a vast new house, in a short period of time, and entertained Elizabeth I there in 1573. By the 18th century the family's fortunes had declined, and the house, renamed Sissinghurst Castle, was leased to the government to act as a prisoner-of-war camp during the Seven Years' War. The prisoners caused great damage to the structure and by the 19th century, following large-scale demolition and use as a workhouse, Sissinghurst had declined to the status of a farmstead.

In 1930, the estate was bought by Vita Sackville-West. Vita and Harold were seeking an alternative refuge after their home Long Barn was threatened by development. Sissinghurst held a strong dynastic appeal for Vita: having seen her ancestral home Knole pass out of her hands in 1928, the ancient home of the Sackvilles exercised an irresistible attraction. Over the next 30 years she and Harold turned a farmstead of "squalor and disorder" into one of the world's most famous gardens. Following Vita's death in 1962, the estate was gifted to the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. It is one of the Trust's most popular properties, receiving nearly 200,000 visitors in 2017.

History

Early history:

The site is ancient; "hurst" is the Saxon term for an enclosed wood. Nigel Nicolson, in his 1964 guide, Sissinghurst Castle: An Illustrated History, records the earliest owners as the de Saxinherst family, followed by the de Berhams.[3] Nicolson suggested that the de Berhams constructed a moated house in stone, of an appearance similar to that of Ightham Mote, which was later replaced by a brick manor.[4] Later studies, including that by Nigel's son, Adam, doubt the existence of the earliest stone manor, suggesting that the brick house, or perhaps a timber construction of slightly earlier date, occupying the corner of the orchard nearest the moat, was the earliest house on the site.[5] It is at this house Edward I is reputed to have stayed in 1305.[6]

Rise, decline, collapse: c.1490-1930

In 1490 the de Berhams sold the manor of Sissinghurst to a Thomas Baker of Cranbrook.[7] The Bakers were cloth producers and in the following century, through marriage and careers at court and in the law, Baker's successors greatly expanded their wealth and their estates in Kent and Sussex.[8] In the 1530s Sir John Baker, one of Henry VIII's Privy Councillors, built a new brick gatehouse, the current West Range.[9] His son, Sir Richard Baker, undertook a massive expansion in the 1560s. The Tower is of his rebuilding, and formed the entrance to a very large courtyard house, of which the South Cottage and some walls are the only other remaining fragments.[10] Sir Richard surrounded the mansion with an enclosed 700-acre (2.8 km2) deer park and in August 1573 entertained Queen Elizabeth I at Sissinghurst.[11]

After the collapse of the Baker family fortunes in the late 17th century, the building declined in importance. Horace Walpole visited in 1752: "yesterday, after twenty mishaps, we got to Sissinghurst for dinner. There is a park in ruins and a house in ten times greater ruins".[12] During the Seven Years' War, it became a prisoner-of-war camp.[13][lower-alpha 1] The historian Edward Gibbon, then serving in the Hampshire militia, was stationed there and recorded "the inconceivable dirtiness of the season, the country and the spot".[15] It was during its use as a camp for French prisoners that the name Sissinghurst Castle was adopted; although it was never a castle, there is debate as to the extent to which the house was a fortified manor.[16] Around 1800, the majority of Sir Richard's Elizabethan house was demolished, the stone and brick reused in buildings throughout the locality.[17] The castle later became a workhouse for the Cranbrook Union, after which it was used to provide accommodation for farm labourers.[18] In 1928, the castle was put up for sale for a price of £12,000, which attracted no interest for some two years.[19]

Vita and Harold: 1930-1968

Vita

Vita Sackville-West, poet, author and gardener, was born at Knole, some 25 miles from Sissinghurst, on 9 March 1892.[20] The great Elizabethan mansion, home of her ancestors and denied to her through primogeniture,[21] held enormous significance for Vita throughout her life.[22] Sissinghurst was a substitute and its familial connections were of great importance to her.[23][24] The Table of Descent set out in her book, Knole And The Sackvilles, records the marriage of Thomas Sackville to Cecily, daughter of Sir John Baker of Sissinghurst Castle, Cranford, Kent in 1554.[25] In 1913 Vita married Harold Nicolson, a diplomat at the start of his career. Their marriage was unconventional, both pursuing multiple, mainly same-sex affairs throughout. Vita's relationship with Violet Trefusis caused the greatest crisis in their marriage; Duff Cooper recorded the London gossip in a diary entry, "(Violet) has behaved very badly and it appears she is now living in Sapphic sin with Vita Nicolson".[26] Having determined to break with Violet in 1921, Vita became ever more withdrawn[27] - she wrote to her mother that she would like "to live alone in a tower with her books", an ambition she achieved in the tower at Sissinghurst[28] where only her dogs were admitted.[29][lower-alpha 2] From 1946 until a few years before her death, Vita wrote a gardening column for The Observer, in which, although she rarely referred to Sissinghurst by name, she discussed a wide array of horticultural issues.[31][lower-alpha 3] In recognition of her achievement at Sissinghurst, in 1955 Vita was awarded the Royal Horticultural Society's Veitch Medal.[33]

-Vita's first impressions of Sissinghurst.[29]

Harold

Harold Nicolson, diplomat, author, diarist and politician, was born in Tehran on 21 September 1886.[34] Following his father into the Diplomatic Corps, he served as a junior member of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference at the end of the First World War,[35] and returned to Iran as Counsellor in 1925.[36] In 1929 he resigned from the Foreign Office [37] to pursue a career in journalism.[38] Thereafter, he combined the careers of journalist, author and politician while maintaining a voluminous diary. His diary entry for 4 April 1930, records, "Vita telephones to say she has seen the ideal house - a place in Kent, near Cranbrook, a sixteenth-century castle".[39]

Building a garden

Sackville-West and Nicolson found Sissinghurst in April 1930,[19] after Dorothy Wellesley, their near neighbour and a former lover of Vita's, saw the estate for sale.[40] Vita and Harold had become increasingly concerned by threats to their property Long Barn, near Sevenoaks, Kent, from encroaching development.[40][lower-alpha 4] Their offer on Sissinghurst was accepted on 6 May[42] and the castle and the farm around it were bought for £12,375. The house had no electricity, nor running water nor drains, and the garden was a wasteland.[40] Clearing the site took almost three years but by 1939 the garden was largely complete, with the exception of The White Garden. Harold was responsible for the design and layout, while Vita, at the head of her team of gardeners, undertook the planting. Simon Jenkins, the architectural writer, describes Harold's style as "post-Picturesque, a garden not as an imitation of nature but as imitation of a house", and suggests his thinking was much influenced by Lawrence Johnston's garden at Hidcote.[29]

Harold and Vita converted the buildings scattered around the site to become their home. Part of the long brick gatehouse range from Sir John Baker's construction of c.1533 became the library, or Big Room;[11] the tower gatehouse dating from Richard Baker's in 1560-1570 became Vita's sitting room, study and sanctuary.[11] The Priest's House was home to their sons Ben and Nigel, and held the family dining room, while the South Cottage housed their bedrooms and Harold's writing room.[43]

Vita and Harold first opened the garden to the paying public for two days in the summer of 1938. Thereafter, the opening hours were gradually increased.[44] Vita came greatly to enjoy her encounters with visitors, known as "shillingses" on account of the entrances fees they deposited in a bowl at the entrance.[45] She described her relationship with them in a 1939 article in the New Statesman; "between them and myself a particular form of courtesy survives, a gardener's courtesy". Harold was known to be less welcoming.[44]

Harold's diary entry for 26 September 1938 records the tense European atmosphere at the time of the Munich Crisis. "They are making the big room at Sissinghurst gas-proof. I know one who will not be there. He will be in his bed minus gas-mask and with all the windows open."[46] During the Second World War, Sissinghurst saw much of the Battle of Britain, which was mainly fought over the Weald of Kent and the English Channel. Harold's diary entry for 2 September 1940 reads, "a tremendous raid in the morning and the whole upper air buzzes and zooms with the noise of aeroplanes. There are many fights over our sunlight fields".[47][lower-alpha 5]

In 1956, the BBC proposed making a television programme at Sissinghurst. Vita was in favour, but Harold was opposed. "I have a vague prejudice against (a) exposing my intimate affections to the public gaze; (b) indulging in private theatricals."[49] Despite latter withdrawing his objections, Vita declined the BBC's offer to please him.[49] In 1959 CBS broadcast a four-way discussion from the dining room at the Priest's House between Harold, Ed Murrow the journalist, and the diplomats Chip Bohlen and Clare Boothe Luce. Vita intensely disliked the result.[50]

Vita died in the first-floor bedroom of the Priest's House on 2 June 1962.[51] Her husband recorded her passing in his diary, "Ursula[lower-alpha 6] is with Vita. At about 1.5 she observes that Vita is breathing heavily, and then suddenly is silent. She dies without fear or self-reproach. I pick some of her favourite flowers and lay them on her bed".[53] Her death devastated Harold - "Oh Vita, I have wept buckets for you" - and his last years were not happy.[54] Giving up his Albany apartment in May 1965, he retired to Sissinghurst which he never left thereafter.[55] He died of a heart attack in his bedroom at the South Cottage on 1 May 1968.[56]

Nigel

-Vita's reaction to the suggestion that Sissinghurst might be gifted to the National Trust.[57]

Nigel Nicolson had always been devoted to his father and admiring of his, more distant, mother[58] and preserving Sissinghurst was "an act of intense filial duty".[59] He had first raised the possibility of giving the house and garden to the National Trust in 1954 but Vita was violently opposed. [57] After her death in 1962, which saw the castle pass to Nigel, he began lengthy negotiations to seek to ensure the handover. The Trust was cautious: it felt an endowment beyond the Nicolson's means would be required, and it was also unsure that the garden was of sufficient importance to warrant acceptance. Sir George Taylor, Chairman of the National Trust's Gardens Committee doubted it was "one of the great gardens of England" and had to be persuaded as to its merits by Vita's close friend, and one-time lover,[60] the gardener Alvilde Lees-Milne.[61][lower-alpha 7] Discussions continued until, in April 1967, the castle, garden and Sissinghurst Farm were finally accepted, the Trust taking formal control on 6 April 1967.[63]

Although always intending to transfer Sissinghurst to the Trust, Nigel undertook significant remodelling at the castle. Unwilling to live in four separate structures, the Big Room, the Tower, the Priest's House and the South Cottage, an inconvenience which had never troubled his parents, he built a substantial family home in the half of the entrance range that stood on the other side of the gateway from the Long Library.[51] He died at the castle on 23 September 2004.[64]

The National Trust: 1968-2018

The National Trust took over the whole of Sissinghurst, its garden, farm and buildings, in 1967.[61] It is among the Trust's most popular properties, receiving nearly 200,000 visitors in 2017.[65] The castle was one of the sites chosen in 2017 as a focus for the celebration of the LGBTQ history of Trust buildings.[66] In the same year, the Trust opened the South Cottage to visitors for the first time.[67]

Adam

Adam Nicolson, Nigel's son and the resident donor after the latter's death, and his wife Sarah Raven have worked to restore a form of traditional Wealden agriculture to Sissinghurst Farm, aiming to reunite the garden with its wider landscape.[68] Their efforts are recorded in Adam's 2008 book, Sissinghurst: An Unfinished History and in a BBC Four documentary Sissinghurst, broadcast in 2009 [69] and have generated some controversy.[70]

Architecture and description

The castle and its garden are listed Grade I with many other structures within the garden having their own listings.[33]

Buildings

West Range

This forms part of Sir John Baker's original house, of the 1530s.[71][lower-alpha 8]Vita and Harold enlisted the assistance of A. R. Powys, architect and the Secretary of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to convert the northern end, formerly stables, into the library, known as the Big Room. Powys provided most of the architectural input into the conversion of the buildings at Sissinghurst, including the Priest's House and South Cottage, as well as occasionally advising on elements of the design of the gardens.[73] The library contains a portrait of Vita from 1910 by Philip de László.[lower-alpha 9] Vita disliked it intensely and it was kept in an attic until the Trust placed it in the Big Room after taking ownership of Sissinghurst. The room as a whole is a recreation of Knole, "Vita's record of her disinheritance".[74] The range is of brick, and of two storeys, with attics and decorated gables and chimneys. The wing to the south was converted to a family home by Nigel. The coat of arms of the Carnocks above the entrance archway was brought to Sissinghurst by Harold.[72][lower-alpha 10] The West Range has a Grade I listing.[72]

Tower

The tower is of brick and was the entrance to the cour d'honneur of the 1560's rebuilding.[71] Of four storeys, it has recessed staircase turrets to each side, creating what the architectural historian Mark Girouard described as an "extraordinarily slender and elegant" appearance.[77] The courtyard was open on the tower side, its three facades pierced by no fewer than seven classical doorways. Girouard notes Horace Walpole's observation of 1752, "perfect and very beautiful".[78] Such an arrangement of a three-sided courtyard with a prominent gatehouse set some way in front became popular from Elizabethan times, similar examples being Rushton Hall and the original Lanhydrock.[79] The Tower was Vita's sanctum, her study was out-of-bounds to all but her dogs and a small number of guests by prior invitation.[80][lower-alpha 11] It is maintained largely as it was at the time of her death. In Portrait of a Marriage, Nigel records his discovery in the turret room off her study of the autobiographical manuscript in which Vita described her affair with Violet Trefusis, and which subsequently formed the basis of the book.[82] The Tower has a Grade I listing.[83]

Priest's House

.jpg)

The architectural historian John Newman suggests that this building was a "viewing pavilion or lodge".[71] Its name derives from the tradition that it was used to house a Catholic priest, the Baker family having long been Catholic adherents.[84] Harold and Vita converted the cottage to provide accommodation for Ben and Nigel, and the family kitchen and dining room. Of red brick and two storeys, the NHLE listing, which records its Grade II* status, suggests that it may have been originally attached to Sir Richard Baker's 1560's house[85] but Newman disagrees.[71]

South Cottage

This building comprised the south-east corner of the courtyard enclosure buildings.[71] It was sensitively restored by Beale & Son, builders from Tunbridge Wells, and provided Harold and Vita's, separate, bedrooms, a shared sitting room and Harold's writing room.[43] Harold's diary entry for 20 April 1933 records, "My new wing has been done. The sitting room is lovely...My bedroom, w.c. and bathroom are divine".[76] Of two storeys in red brick, with an extension dating from the 1930s, South Cottage has a Grade II* listing.[86]

Gardens

.jpg)

Anne Scott-James, an early historian of the garden, set out the principles of Vita and Harold's design: "a garden of formal structure, of a private and secret nature, truly English in character, and plant(ed) with romantic profusion".[87] Harold largely undertook the design and Vita the planting. The garden is designed as a series of 'rooms', each with a different character of colour and/or theme, the walls being high clipped hedges and many pink brick walls.[88] The rooms and 'doors' are so arranged as to offer glimpses into other parts of the garden. Vita described the overall design; "a combination of long axial walks, usually with terminal points, and the more intimate surprise of small geometrical gardens opening off them, rather as the rooms of an enormous house would open off the corridors".[87] Harold considered the garden's success was down to this "succession of privacies: the forecourt, the first arch, the main court, the tower arch, the lawn, the orchard. All a series of escapes from the world, giving the impression of cumulative escape".[89]

-William Robinson, author of The English Flower Garden and a major influence on Vita's planting style[90]

Edwin Lutyens, long-time gardening partner of Gertrude Jekyll, was a frequent visitor to Long Barn and advised Vita regarding Sissinghurst.[91] Vita denied that Jekyll's work had an impact on her own designs but Nigel Nicolson described Lutyens' influence on Sissinghurst as "pervasive".[91] Fleming and Gore go further, suggesting that Vita's use of groupings of colours "followed Jekyll"; "a purple border, a cottage garden in red, orange and yellow, a walled garden pink (and) purple, a white garden, a herb garden".[92] Scott-James notes, however, that herbaceous borders, "Jekyll's speciality", were much disliked by Vita.[90] Other influencers, and friends, were the noted plantswoman Norah Lindsay, their neighbour at Benenden, the plant collector Collingwood Ingram[93] and Reginald Cooper, whose earlier garden at Cothay Manor in Somerset has been described as the "Sissinghurst of the West Country".[94]

Vita's planting philosophy is summed up in the advice contained in one of her regular gardening columns in the Observer newspaper; "Cram, cram, cram, every chink and cranny".[95] The garden's most recent historian, Sarah Raven, writes of Vita's use of vertical axes, as well as the horizontal in her planting. Assisted by the number of walls still standing from the Tudor manor, and constructing more of her own, Vita remarked "I see we are going to have heaps of wall space for climbing things".[96]

John Vass, appointed head gardener in 1939,[97] left in 1957.[98] Called up to the RAF in 1941, he exhorted Vita to maintain the hedges, assuring her that everything else in the garden could be restored after the war.[99] In 1959 Vita appointed Pamela Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger as joint replacements.[100] They remained at Sissinghurst until 1991, their contributions, "as much, if not more" than Vita's, making the garden "the most admired and popular 20th-century garden in England".[101]

The pair were followed as head gardener by Sarah Cook[102] who was succeeded by Alexis Datta.[103] In 2014, Troy Scott-Smith, the first male head gardener at Sissinghurst since John Vass in the 1950s, was appointed, writing of the challenges of maintaining the garden "in the manner of its creator, after they have gone".[104]

The gardening writer and landscape critic Tim Richardson, writing in 2015, described Scott-Smith's re-making of the garden; "Sissinghurst, more than any other garden I know, inspires extremes of emotion. There is a feeling that this is Britain’s leading garden – and so, arguably, the world’s, a status that has proven to be both a great boon and an albatross around its neck". Scott-Smith's plans include the reinstatement of every species of rose known to have been grown by Vita.[105][lower-alpha 12] A new history of the garden was published in 2014.[107]

Top Courtyard and Tower Lawn

.jpg)

Entered through the archway in the West Range that had been blocked for over 100 years before Vita and Harold's arrival, the Top Courtyard is dominated by the Tower.[108] Planted against a new wall constructed on ancient foundations is the Purple Border, a colour palette deliberately chosen by Vita in defiance of Gertrude Jekyll's dictum against massing purple flowers.[109] The gardening writer Tony Lord considers it "the courtyard's greatest glory".[110] The height of the Tower causes considerable turbulence which necessitates intensive staking of the plants[111], particularly the taller specimens such as Vita’s much favoured Rosa moyesii.[112] On the opposite side of the Tower is the Tower Lawn, also known as the Lower Courtyard, Harold emphasising that "the English lawn is the basis of our garden design".[108] The west-east vista from the Top Courtyard through the Tower gateway, across the Tower Lawn and to the statue of Dionysus across the moat forms one of Harold's most important visual axes. It bisects the north-south axis running from the White Garden, across Tower Lawn to the Roundel in the Rose Garden.[113]

White Garden

"A symphony in subtle shades of white and green",[114] the White Garden is considered the "most renowned" and most influential of all of Sissinghurst's garden rooms.[115] Planned before the war, it was completed in the winter of 1949-1950.[116] Using a palette of white, silver, grey and green, it has been called "one of Vita and Harold’s most beautiful and romantic visions".[117] Vita recorded her original inspiration in a letter to Harold date 12 December 1939, "I have got what I hope will be a lovely scheme for it: all white flowers, with some clumps of very pale pink".[118] The concept of single colour-palette gardens had enjoyed some popularity at the end of the 19th century, but the numbers of such gardens remaining when Vita drew up her plans were few. Influences for the White Garden are given as Hidcote and Phyllis Reiss's garden at Tintinhull, both of which Vita had seen.[119] Gertrude Jekyll had discussed the concept, but argued for varying the white palette with the use of blue, or yellow, plants, advice followed by Reiss. But neither equals the "full-scale symphony" of the White Garden at Sissinghurst.[119] A more prosaic motivation for the colour scheme was to provide illumination for Vita and Harold as they made their way from their bedrooms at the South Cottage to the Priest's House for dinner.[120]

-Vita's reflections on Sissinghurst towards the end of her life.[107]

The central focal point of the garden was originally four almond trees, encased in a canopy of the white rose, R.Mulliganii. By the 1960s, the weight of the roses had severely weakened the trees, and they were replaced with an iron arbour designed by Nigel.[121] Beneath the arbour is sited a Ming dynasty vase brought by Harold from Cairo.[122] After a severe winter following Vita's death, Hilda Murrell supplied Rosa Iceberg to supplement losses.[123] A lead statue of a Vestal Virgin, cast by Toma Rosandić from the wooden original which is in the Big Room, presides over the garden. Vita intended that the statue be enveloped by a weeping pear tree Pyrus salicifolia-'Pendula' and the present tree was planted after her original was destroyed in the Great Storm of 1987.[124] Lord considers the White Garden "the most ambitious and successful of its time, the most entrancing of its type".[125]

A, possibly apocryphal, story records a visit by the colour-obsessed gardener, Christopher Lloyd, during which he is supposed to have scattered nasturtium seeds across the lawn.[126]

Rose Garden

The Rose Garden was constructed on the site of the old kitchen garden from 1937.[127] The use of "Old roses", those bred before 1867, formed the heart of the garden's planting.[128] Such roses appealed to Vita for their lavish appearance, but also for their history. The Rosa × centifolia-R.Gallica, believed to have been introduced from Persia in the 7th century, and Felicite et Perpetue, named after two early Christian women martyrs, were among her favourites.[129] The informal and unstructured massing of the plants was Vita's deliberate choice, and has become one of Sissinghurst's defining features.[130] Roses were supplied by, among others, Hilda Murrell of Edwin Murrell Ltd., notable rose growers in Shropshire.[130] The Rose Garden is divided by the Roundel, constructed of yew hedging by Harold and Nigel in 1933.[127] As elsewhere in the garden, the Trust has replaced the original grass paths with those in stone and brick, to cope with the huge increases in visitor numbers.[131] Anne Scott-James considered the roses in the Rose Garden "one of the finest collections in the world".[132]The writer Jane Brown describes the Rose Garden, more than any other including the White, as expressing, "the essence of Vita's gardening personality, just as her writing-room enshrines her poetic ghost".[133]

Delos and Erechtheum

Delos, between the Priest's House and the courtyard wall, was the one area of the garden that neither Harold nor Vita considered a success.[134] Vita explained its origins in an article in Country Life in 1942. It was inspired by terraced ruins covered with wild flowers she had observed on the island of Delos.[125] Neither the shade nor the soil, nor its inter-relationships with other parts of the garden, have proved satisfactory, either in the Nicolson's time or subsequently.[125] The Erechtheum, named after one of the temples at the Acropolis, comprises a vine-covered loggia and was used by Vita and Harold as a place for eating outside.[115]

Cottage and Herb Gardens

The dominating colours in the cottage garden are red, orange and yellow,[135] a colour scheme that both Vita and Harold claimed as their own conception. Lord considers it as much a traditional "cottage garden as Marie Antoinette was a milkmaid"[136] Here, as elsewhere, Vita was much influenced by William Robinson, a gardener she greatly admired and who had done much to popularise the concept of a cottage garden. It comprises four beds, surrounded by simple paths, with planting in colours that Vita described as of the sunset.[137]

The Herb Garden contains sage, thyme, hyssop, fennel and an unusual seat constructed around a camomile bush.[33] Known to the family as Edward the Confessor's chair, it was constructed by Copper, the Nicolson's chauffeur.[138] Originally laid out by Vita in the 1930s, the garden was revitalised by John Vass in the years immediately after the Second World War.[139] The Lion Basin in the centre of the garden was brought back by Harold and Vita from Turkey in 1914.[140] Most of the over one hundred herbs in the garden are now raised in the nurseries and planted out at appropriate times of year.[141]

Walks and the moat

The Lime Walk, also known as the Spring Garden, was the one part of Sissinghurst where Harold undertook the planting as well as the design.[142] He had originally intended a single axis running straight from the Rose Garden, through the Cottage Garden and then the Nuttery to the moat but the topography of the site precluded this. Instead, an angled walk was established in the mid-1930s, and substantially replanted in 1945-1962.[143] Vita was critical of the angularity of the design, comparing it to Platform 5 at Charing Cross station, but treasured it as Harold's creation. "I walked down the Spring Garden and all your little flowers tore and bit at my heart. I do love you so, Hadji.[lower-alpha 13] It is quite simple: I do love you so. Just that."[142] The limes are pleached and the dominant plant is Euphorbia polychorma Major.[145] Harold kept meticulous gardening records of his efforts in the Lime Walk from 1947 to the late 1950s and, providing consolation after the end of his parliamentary career, he described the walk as "My Life's Work".[146]

The Yew Walk runs parallel to the Tower Lawn. Its narrow width has been problematic and by the late 1960s, the yew hedges were dying. Extensive pruning proved successful in revitalizing the avenue.[147]

The Nuttery was famed in Vita and Harold's time for its carpet of polyanthus. Harold called it "the loveliest planting scheme in the whole world".[148] By the 1960s, the plants were dying, and attempts to improve the soil did not assist. The carpet was replaced from the 1970s by a mixture of woodland flowers and grasses.[148]

The Moat Walk stands on the old bowling green constructed by Sir Richard Baker in the 1560s[149] and his, reconstructed, moat wall provides the axis.[150][lower-alpha 14] The azaleas were bought by Vita with the £100 Heinemann prize she received in 1946 for her last published poem, The Land.[149] The notable wisteria were a gift from Vita's mother, Lady Sackville, as were the six bronze vases.[150] A bench designed by Lutyens terminates one end of the walk, the other focal point being the statue of Dionysus.[152] The two sides of the moat which remain from the medieval house are populated by goldfish, carp and Golden Orfe.[153]

Orchard

The Orchard was an unproductive area of fruit trees where Harold and Vita arrived. The unplanned layout was retained as a contrast to the formality of the majority of the garden, the fruit trees were paired with climbing roses and the area provided space for the many gifts of plants and trees they received.[154] This part of the garden suffered particularly severe losses in the Great Storm of 1987 and much replanting has taken place.[155] The Orchard is the setting for two structures planned by Nigel and commissioned in memory of his father, the boathouse and the gazebo.[156] The gazebo, of 1969, is by Francis Pym and has a candlesnuffer roof intended to evoke those of Kentish oast houses. The boathouse, of timber construction and with Tuscan colonnades dates from 2002 and is by the local architectural firm Purcell Miller Tritton.[71] Nigel had always felt that the only memorial at Sissinghurst failed to acknowledge his father’s contribution. The words “Here lived V. Sackville-West who made this garden” were chosen by Harold.[157]

Plants

- Between the apple-blossom and the water -

- She walks among the patterned pied brocade,

- Each flower her son and every tree her daughter."

-Extract from Vita's poem The Land which was printed on the service-sheet for her funeral.[158]

Sissinghurst has given its name to several cultivars of garden plants which were developed there, notably:-

- Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Sissinghurst Blue’[159]

- Glandularia ‘Sissinghurst’[159]

- Pulmonaria ‘Sissinghurst White’[159]

Access

Sissinghurst Castle Gardens are open daily from March to October.[160]

Footnotes

- ↑ An 18th painting of the castle at this time was identified as being of Sissinghurst only in 2008. Showing the house before its destruction, it is the most complete record of the house as built by Sir Richard Baker. The painting is reproduced on the inside front cover of Adam Nicolson's book, Sissinghurst: an unfinished History.[14]

- ↑ Vita consciously designed Sissinghurst without any guest accommodation, as her dislike of visitors and love of solitude came to be dominant features in her character. Nigel Nicolson recorded his mother's explanation for requiring that he and his brother share a bedroom until they went to university. "If we had a bedroom each and one of us was away Lady Colefax might find out and invite herself for the weekend."[30]

- ↑ These were subsequently published in four volumes by Michael Joseph; In your Garden (1951), In Your Garden Again (1953), More For Your Garden (1955) and Even More for Your Garden (1958).[32]

- ↑ In 1925, they had considered Bodiam Castle as an alternative to Long Barn. Their plan was for Vita, Harold, Ben and Nigel each to inhabit one of the four concentric towers.[41]

- ↑ Although Sissinghurst was undamaged, Knole was bombed in 1944. This prompted Vita into violent reaction. "I mind frightfully, frightfully, frightfully. I always persuade myself that I have finally torn Knole out of my heart, and then the moment anything touches it, every nerve is alive again. I cannot bear to think of Knole wounded. Those filthy Germans! Let us level every town in Germany to the ground! I shan't care."[48]

- ↑ Ursula Codrington was Vita's secretary from 1959.[52]

- ↑ The Trust had, at this time, taken on relatively few gardens. Bodnant had come in 1949 and Nymans in 1954. Perhaps the most significant for Sissinghurst had been Hidcote, accepted largely at Vita's urging through her membership of the Trust's Gardens Committee.[62]

- ↑ The National Heritage List for England gives a date of 1490, some forty years earlier.[72]

- ↑ Vita's mother, Lady Sackville asked de László, "Do you not think that you owe it to your art and to her beauty to paint her without a fee?"[74]

- ↑ Harold's father Arthur was made 1st Baron Carnock in 1916.[75] Harold's diary entry for 20 April 1933 records, "Vita and the boys pick me up and we motor down to Sissinghurst. Arrive soon after eight. The arms are on the porch".[76] The arms are dated 1548.[71]

- ↑ Nigel recalled that, at her death, he had only been up to Vita's tower room on about six occasions in 30 years.[81]

- ↑ John Vass retained a Hilling's nursery catalogue from 1953. This showed 170 of the roses within it as being planted at Sissinghurst and he recalled at least 24 other varieties not included within the catalogue.[106]

- ↑ "Hadji", meaning pilgrim, was Sir Arthur Nicolson's nickname for his son which Vita adopted and used throughout their marriage. Harold's nickname for Vita was "Mar", a diminutive first used by Vita's mother.[144]

- ↑ Jane Brown suggests it is older, dating from the house of the de Berhams.[151]

References

- ↑ "Sissinghurst Garden". www.gardenvisit.com. The Garden Guide. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, p. 285.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, pp. 173-174.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, p. 5.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, p. 6.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Newman 2012, p. 544.

- ↑ Newman 2012, pp. 544-545.

- 1 2 3 Greeves 2008, p. 285.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, p. 24.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 44.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, Preface.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ "Sissinghurst Castle". www.gatehouse-gazetteer.info. The Gatehouse Gazetteer Guide. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 1964, p. 42.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 45.

- 1 2 Nicolson 1964, p. 44.

- ↑ Glendinning 1983, p. 1.

- ↑ Glendinning 1983, p. 9.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 24.

- ↑ Glendinning 1983, p. 224.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 23.

- ↑ Sackville-West 1991, Forward ix.

- ↑ Cooper 2005, p. 140.

- ↑ Nicolson 1990, p. 211.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 2003, p. 381.

- ↑ Nicolson 1992, p. 10.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 33.

- ↑ Raven 2014, p. 367.

- 1 2 3 England, Historic. "Vita Sackville-West and Sissinghurst Castle - Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 2.

- ↑ Lees-Milne 1980, p. 109.

- ↑ Lees-Milne 1980, p. 240.

- ↑ Rose 2006, pp. 162-163.

- ↑ Lees-Milne 1980, p. 389.

- ↑ Nicolson 1966, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Nicolson 2008b, p. 46.

- ↑ Raven 2014, p. 38.

- ↑ Nicolson 1966, p. 48.

- 1 2 Brown 1990, pp. 95-96.

- 1 2 Scott-James 1974, p. 67.

- ↑ Raven 2014, p. 348.

- ↑ Nicolson 1966, p. 366.

- ↑ Nicolson 1967, p. 110.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 99.

- 1 2 Nicolson 1968, p. 300.

- ↑ Nicolson 1968, pp. 373-374.

- 1 2 Nicolson 1964, p. 47.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 112.

- ↑ Nicolson 1968, p. 415.

- ↑ Nicolson 1990, pp. 216-218.

- ↑ Lees-Milne 1981, p. 352.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 299.

- 1 2 Nicolson 1968, p. 268.

- ↑ Nicolson 1990, p. 212.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, p. 445.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 83.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 18.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 44.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, p. 48.

- ↑ de-la-Noy, Michael (24 September 2004). "Obituary: Nigel Nicolson". www.guardian.com. the Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Latest Visitor Figures - 2017". www.alva.org.uk. ALVA-Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (21 December 2016). "National Trust prepares to celebrate its gay history". www.theguardian.com. the Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Sturt, Sarah (16 January 2017). "South Cottage opens at Sissinghurst Castle Garden". Kent Life. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Horsford, Simon; Naughton, Pete (23 February 2009). "Sissinghurst-BBC iPlayer". the Telegraph. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ McSmith, Andy (20 February 2009). "Secateurs at dawn at Sissinghurst". the Independent. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Newman 2012, pp. 544-546.

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "West Range At Sissinghurst Castle, Cranbrook - 1346285". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 30.

- 1 2 Nicolson 2008b, p. 12.

- ↑ The National Archives. "Sir Arthur Nicholson, 1st Baron Carnock: Papers". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- 1 2 Nicolson 1966, p. 147.

- ↑ Girouard 2009, p. 97.

- ↑ Girouard 2009, p. 171.

- ↑ Girouard 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 54.

- ↑ Raven 2014, p. 45.

- ↑ Nicolson 1990, p. 7.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tower and Walls 30 yards East of the West Range at Sissinghurst Castle, Cranbrook - 1084163". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 42.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Priest's House at Sissinghurst Castle, Cranbrook - 1346286". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "The South Cottage, Cranbrook - 1084164". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- 1 2 Scott-James 1974, p. 38.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 12.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 111.

- 1 2 Scott-James 1974, p. 41.

- 1 2 Brown 1982, p. 183.

- ↑ Fleming & Gore 1988, p. 220.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 69.

- ↑ "Cothay Manor Gardens". www.gardens-guide.com. Gardens Guide. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ Allsup, Daisy. "From Sissinghurst to Chartwell - the best gardens to visit in Kent". houseandgarden.co.uk. House & Garden. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Raven, Sarah (18 April 2014). "Sissinghurst: Vita Sackville-West's lavish approach to gardening". www.telegraph.co.uk. the Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 46.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 15.

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 47.

- ↑ "Pamela Schwerdt obituary". www.telegraph.co.uk. the Daily Telegraph. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 52.

- ↑ Thomas, Alex (6 May 2013). "Just the man for the greatest job in gardening". www.telegraph.co.uk. the Telegraph. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Scott-Smith, Troy (12 June 2014). "Sissinghurst: The Iconic Garden". www.theenglishgarden.co.uk. The English Garden. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Richardson, Tim (6 May 2015). "A garden makeover at Sissinghurst". www.telegraph.co.uk. the Telegraph. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 105.

- 1 2 Kellaway, Kate (9 March 2014). "Vita Sackville-West's Sissinghurst review – a wealth of inspiration for gardeners". www.guardian.com. the Guardian.

- 1 2 Nicolson 2008b, p. 10.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 11.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 23.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 28.

- ↑ Raven 2014, p. 359.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 35.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 5.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 128.

- ↑ Nevins 1984, pp. 1332-1339.

- ↑ Helen Champion. "A moonlit masterpiece at Sissinghurst Castle Garden". nationaltrust.org.uk. National Trust. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Nicolson 1967, p. 48.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 129.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 127.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 32.

- ↑ "The White Garden Rose (Rosa mulliganii)". Sissinghurst Gardeners Blog. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 135.

- ↑ Brown 1990, pp. 126-127.

- 1 2 3 Lord 1995, p. 147.

- ↑ Clayton 2013, p. 41.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 46.

- ↑ "The history of Sissinghurst's roses". countrylife.co.uk. Country Life. 28 June 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 74.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 47.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 76.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 73.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 77.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 35.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 18.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 76.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 99.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 100.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 110.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 111.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 112.

- 1 2 Nicolson 2008b, p. 16.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 66.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 47.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 69.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 89.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 37.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 90.

- 1 2 Nicolson 2008b, p. 22.

- 1 2 Lord 1995, p. 100.

- ↑ Brown 1990, p. 103.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 108.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 126.

- ↑ Lord 1995, p. 118.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 27.

- ↑ Nicolson 2008b, p. 26.

- ↑ Raven 2014, pp. 31-34.

- ↑ Scott-James 1974, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Lord 1995, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ "Opening Times - Sissinghurst Castle Garden - National Trust". www.nationaltrust.org.uk. National Trust. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

Sources

- Brown, Jane (1982). Gardens Of A Golden Afternoon. London UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-06708-0640-9.

- — (1998). Sissinghurst - Portrait of a Garden. London, UK: Orion Books. ISBN 978-07538-0437-7.

- Clayton, Phil (2013). Sissinghurst Castle Garden (PDF). London: Royal Horticultural Society.

- Cooper, Duff (2005). John Julius Norwich, ed. The Duff Cooper Diaries: 1915-1951. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84843-1.

- Fleming, Laurence; Gore, Alan (1988). The English Garden. London UK: Spring Books. ISBN 978-06005-5728-9.

- Girouard, Mark (2009). Elizabethan Architecture: Its Rise and Fall, 1540-1640. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-03000-9386-5.

- Glendinning, Victoria (2005). Vita - The Life of V. Sackville-West. London, UK: Orion Books. ISBN 978-0-7538-1926-5.

- Greeves, Lydia (2008). Houses of the National Trust. London, UK: National Trust Books. ISBN 978-19054-0066-9.

- Jenkins, Simon (2003). England's Thousand Best Houses. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-07139-9596-1.

- Lees-Milne, James (1980). Harold Nicolson: A Biography 1886-1929. 1. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-07011-2520-2.

- — (1981). Harold Nicolson: A Biography 1930–1968. 2. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-07011-2602-5.

- Lord, Tony (1995). Gardening at Sissinghurst. London, UK: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-07112-0991-6.

- Nevins, Deborah (1984). The garden at Sissinghurst Castle, Kent (PDF). Kent: Kent Magazine.

- Newman, John (2012). Kent: West and The Weald. The Buildings of England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-03001-8509-6.

- Nicolson, Adam (2008). Sissinghurst - An Unfinished History. London, UK: Harper Press. ISBN 978-00072-4054-8.

- — (2008b). Sissinghurst. London, UK: National Trust. ISBN 978-18435-9300-3.

- Nicolson, Harold (1966). Nigel Nicolson, ed. Diaries and Letters: 1930-1939. London, UK: William Collins, Sons. OCLC 874514916.

- — (1967). Nigel Nicolson, ed. Diaries and Letters: 1939-1945. London, UK: William Collins, Sons. OCLC 264742347.

- — (1968). Nigel Nicolson, ed. Diaries and Letters: 1945-1962. London, UK: William Collins, Sons. OCLC 264742357.

- Nicolson, Nigel (1964). Sissinghurst Castle – An illustrated history. London, UK: National Trust. OCLC 39835087.

- — (1990). Portrait of a Marriage. London, UK: Guild Publishing. OCLC 50979846.

- — (1992). Vita & Harold - The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson 1910-1962. London, UK: Orion Books. ISBN 978-1-85799-061-4.

- Raven, Sarah (2014). Sissinghurst - Vita Sackville-West and the Creation of a Garden. London, UK: Virago Press. ISBN 978-18440-8896-6.

- Rose, Norman (2006). Harold Nicolson. London, UK: Pimlico. ISBN 978-07126-6845-3.

- Sackville-West, Vita (1991). Knole And The Sackvilles. London UK: The National Trust. OCLC 91730091.

- Scott-James, Ann (1974). Sissinghurst - The Making of a Garden. London, UK: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-07181-2256-0.

Further reading

- Brown, Jane (1985). Vita's Other World: A Gardening Biography of V. Sackville-West. Harmondsworth, UK and New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-06708-0163-3.

- Lord, Tony (2003). Planting Schemes from Sissinghurst. London, UK: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-07112-1788-1.

See also

- History of gardening (with a list of notable historical gardens)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sissinghurst Castle. |