Silphium

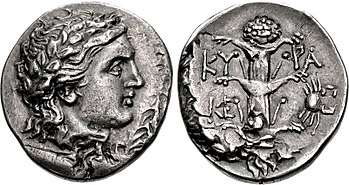

Silphium (also known as silphion, laserwort, or laser) was a plant that was used in classical antiquity as a seasoning, perfume, as an aphrodisiac, or as a medicine.[1][2] It was the essential item of trade from the ancient North African city of Cyrene, and was so critical to the Cyrenian economy that most of their coins bore a picture of the plant. The valuable product was the plant's resin (laser, laserpicium, or lasarpicium).

Silphium was an important species in prehistory, as evidenced by the Egyptians and Knossos Minoans developing a specific glyph to represent the silphium plant.[3] It was used widely by most ancient Mediterranean cultures; the Romans who mentioned the plant in poems or songs, considered it "worth its weight in denarii" (silver coins), or even gold.[2] Legend said that it was a gift from the god Apollo.

The exact identity of silphium is unclear. It is commonly believed to be a now-extinct plant of the genus Ferula,[1] perhaps a variety of "giant fennel". The still-extant plants Margotia gummifera[4] and Ferula tingitana[5] have been suggested as other possibilities. Another plant, asafoetida, was used as a cheaper substitute for silphium, and had similar enough qualities that Romans, including the geographer Strabo, used the same word to describe both.[6]

Identity and extinction

The identity of silphium is highly debated. It is generally considered to belong to the genus Ferula, probably as an extinct species (although the currently extant plants Margotia gummifera,[4] Ferula tingitana, Ferula narthex, and Thapsia garganica have historically been suggested as possible identities).[1][5][7] K. Parejko, writing on its possible extinction, concludes that "because we cannot even accurately identify the plant we cannot know for certain whether it is extinct".[8] Theophrastus mentioned Silphium as having thick roots covered in black bark, about 48 centimeters long, or one cubit, with a hollow stalk, similar to fennel, and golden leaves, like celery.[2]

The cause of silphium's supposed extinction is not entirely known. The plant grew along a narrow coastal area, about 125 by 35 miles (201 by 56 km), in Cyrenaica (in present-day Libya).[9] Much of the speculation about the cause of its extinction rests on a sudden demand for animals that grazed on the plant, for some supposed effect on the quality of the meat. Overgrazing combined with overharvesting may have led to its extinction.[10] Demand for its contraceptive use was reported to have led to its extinction in the third or second century BCE.[11] The climate of the Maghreb has been drying over the millennia, and desertification may also have been a factor.

Another theory is that when Roman provincial governors took over power from Greek colonists, they over-farmed silphium and rendered the soil unable to yield the type that was said to be of such medicinal value. Theophrastus wrote in Enquiry into Plants that the type of ferula specifically referred to as "silphium" was odd in that it could not be cultivated.[12] He reports inconsistencies in the information he received about this, however.[13] This could suggest the plant is similar sensitive to soil chemistry as Huckleberries are, which when grown from seed are devoid of fruit.[2]

Similar to the soil theory, another theory holds that the plant was a hybrid, which often results in very desired traits in the first generation, but second-generation can yield very unpredictable outcomes. This could have resulted in plants without fruits, when planted from seeds, instead asexually reproducing through their roots.[2]

Pliny reported that the last known stalk of silphium found in Cyrenaica was given to the Emperor Nero "as a curiosity".[10]

Folk medicine

Many medical uses were ascribed to the plant.[14] It was said that it could be used to treat cough, sore throat, fever, indigestion, aches and pains, warts, and all kinds of maladies. Hippocrates wrote:[15]

When the gut protrudes and will not remain in its place, scrape the finest and most compact silphium into small pieces and apply as a cataplasm.

The plant may also have functioned as a contraceptive and abortifacient.[5][16][17][18] Many species in the parsley family have estrogenic properties, and some, such as wild carrot, are known to act as abortifacients.[16]

Culinary uses

Silphium was used in Greco-Roman cooking, notably in recipes by Apicius.

Long after its extinction, silphium continued to be mentioned in lists of aromatics copied one from another, until it makes perhaps its last appearance in the list of spices that the Carolingian cook should have at hand—Brevis pimentorum que in domo esse debeant ("A short list of condiments that should be in the home")—by a certain "Vinidarius", whose excerpts of Apicius[19] survive in one eighth-century uncial manuscript. Vinidarius's dates may not be much earlier.[20]

Connection with the heart symbol

There has been some speculation about the connection between silphium and the traditional heart shape (♥).[21] Silver coins from Cyrene of the 6–5th century BCE bear a similar design, sometimes accompanied by a silphium plant and is understood to represent its seed or fruit.[22] Some plants in the family Apiaceae, such as Heracleum sphondylium, have heart-shaped indehiscent mericarps (a type of fruit).

Contemporary writings help tie silphium to sexuality and love. Silphium appears in Pausanias' Description of Greece in a story of the Dioscuri staying at a house belonging to Phormion, a Spartan, "For it so happened that his maiden daughter was living in it. By the next day this maiden and all her girlish apparel had disappeared, and in the room were found images of the Dioscuri, a table, and silphium upon it."[23] Silphium as Laserpicium makes an appearance in a poem (Catullus 7) of Catullus to his lover Lesbia (though others have suggested that the reference here is instead to silphium's use as a treatment for mental illness, tying it to the "madness" of love[24]).

Heraldry

.svg.png)

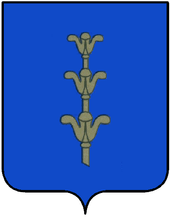

In the Italian military heraldry, Il silfio d’oro reciso di Cirenaica (Silphium of Cyrenaica, smoothly cut and printed in gold; in blazon: silphium couped or of Cyrenaica) is the symbol granted to units that distinguished themselves in the Western Desert Campaign in North Africa during World War II.[25]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 J.L. Tatman, "Silphium, Silver and Strife: A History of Kyrenaika and Its Coinage" Celator 14.10 (October 2000:6–24).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zaria Gorvett (2017). "The mystery of the lost Roman herb". BBC.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2007). "Knossos fieldnotes". Modern Antiquarian. Retrieved 13 Feb 2009.

- 1 2 Amigues, Suzanne (2004). "Le silphium - État de la question". Journal des savants (in French). 2: 191–226.

- 1 2 3 Did the ancient Romans use a natural herb for birth control?, The Straight Dope, October 13, 2006

- ↑ Dalby, page 18.

- ↑ Alfred C. Andrews, "The Silphium of the Ancients: A Lesson in Crop Control"., Isis 33.2 (June 1941:232–236).

- ↑ Parejko, K (2003). "Pliny the Elder's Silphium: First Recorded Species Extinction". Conservation Biology. 17: 925–927. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02067.x.

- ↑ "Off this tract is the island of Platea, which the Cyrenaeans colonized. Here too, upon the mainland, are Port Menelaus, and Aziris, where the Cyrenaeans once lived. The Silphium begins to grow in this region, extending from the island of Platea on the one side to the mouth of the Syrtis on the other." (Herodotus, iv.168–198 on-line text)

- 1 2 Pliny, XIX, Ch.15

- ↑ unspecified (2001). "Herbal contraceptives and abortifacients". In Bullough, Vern L. Encyclopedia of birth control. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 125–128. ISBN 9781576071816.

- ↑ Theophrastus, III.2.1, VI.3.3

- ↑ Theophrastus, VI.3.5

- ↑ Pliny, XXII, Ch. 49

- ↑ Hippocrates, Translated by Francis Adams. "On Fistulae, Section 9".

- 1 2 Riddle, John M. (1994). Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. Harvard University Press. p. 58. ASIN 0674168763. ISBN 978-0674168763.

- ↑ Kolata, Gina (March 8, 1994). "In Ancient Times, Flowers and Fennel For Family Planning". New York Times. p. C1.

- ↑ Rensberger, Boyce (July 25, 1994). "Pharmacology". Washington Post.

- ↑ A generic term for a cookery book, as Webster is of American dictionaries.

- ↑ Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, Anthea Bell, tr. The History of Food, revised ed. 2009, p. 434.

- ↑ Favorito, E. N.; Baty, K. (February 1995). "The Silphium Connection". Celator. 9 (2): 6–8.

- ↑ T. V. Buttrey, "The Coins and the Cult", Expedition magazine vol. 34, Nos. 1–2 "Special Issue: Gifts to the Goddesses—Cyrene's Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone", Spring–Summer 1992.

- ↑ Pausanias, 3.16.3

- ↑ A. C. Moorhouse, "Two Adjectives in Catullus, 7." The American Journal of Philology 84.4 (October 1963:417f); Stephen Bertman, "Oral Imagery in Catullus 7", The Classical Quarterly, New Series, 28.2 (1978), pp. 477–478

- ↑ "Si distinsero i soldati del 28° Reggimento Fanteria "Pavia" il cui scudo reca nel terzo quarto una pianta di silfio d'oro reciso e sormontata da una stella d'argento"." (Gaetano Arena, Inter eximia naturae dona: il silfio cirenaico fra ellenismo e tarda antichità, 2008:13

References

- Amigues, Suzanne (2004). "Le silphium - État de la question". Journal des savants (in French). 2: 191–226.

- Dalby, Andrew (2002). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23674-2.

- Herodotus. The Histories. II:161, 181, III:131, IV:150–65, 200–05.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece 3.16.1–3

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. XIX:15 and XXII:100–06.

- Tatman, John. "Silphium: Ancient wonder drug?". Jencek's Ancient Coins & Antiquities. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- Theophrastus. Enquiry into plants and minor works on odours and weather signs, with an English translation by Sir Arthur Hort, bart (1916). Volume 1 (Books I–V) and Volume 2 (Books VI–IX) Volume 2 includes the index, which lists silphium (Greek σιλϕιον) on page 476, column 2, 2nd entry.

Further reading

- Buttrey, T. V. (1997). "Part I: The Coins from the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone". In D. White (ed.) (ed.). Extramural Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Cyrene Libya, Final Reports: Vol. VI. Philadelphia. pp. 1–66.

- Fisher, Nick (1996). "Laser-Quests: unnoticed allusions to contraception in a poet and a princeps?". Classics Ireland. 3: 73–97. doi:10.2307/25528292. JSTOR 25528292.

- Gemmill, Chalmers L. (July–August 1966). "Silphium". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 40 (4): 295–313. PMID 5912906.

- Helbig, M. (2012). "Physiology and morphology of silphium in Botanical Works of Theophrastus". Scripta Classica. 9: 41–49.

- Koerper, Henry; A. L. Kolls (April–June 1999). "The Silphium Motif Adorning Ancient Libyan Coinage: Marketing a Medicinal Plant". Economic Botany. 53 (2): 133–143. doi:10.1007/BF02866492.

- Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 0-674-27024-X.

- Riddle, John M.; J. Worth Estes; Josiah C. Russell (March–April 1994). "Birth Control in the Ancient World". Archaeology. 47 (2): 29–35.

- Tameanko, M. (April 1992). "The Silphium Plant: Wonder Drug of the Ancient World Depicted on Coins". Celator. 6 (4): 26–28.

- Tatman, J. L. (October 2000). "Silphium, Silver and Strife: A History of Kyrenaika and Its Coinage". Celator. 14 (10): 6–24.

- Wright, W. S. (February 2001). "Silphium Rediscovered". Celator. 15 (2): 23–24.

- William Turner, A New Herball (1551, 1562, 1568)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silphium (ancient plant). |

- Contraception In Ancient Times: Use of Morning-After Pill by David W. Tschanz

- Silphion at Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages

- The Secret of the Heart

- Margotia gummifera

- Ferula tingitana