Silent Hill (video game)

| Silent Hill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo |

| Publisher(s) | Konami |

| Director(s) | Keiichiro Toyama |

| Producer(s) | Gozo Kitao |

| Programmer(s) | Akihiro Imamura |

| Writer(s) | Keiichiro Toyama |

| Composer(s) | Akira Yamaoka |

| Series | Silent Hill |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Survival horror |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

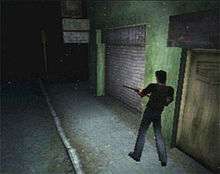

Silent Hill[lower-alpha 1] is a survival horror video game for the PlayStation published by Konami and developed by Team Silent, a group in Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo. The first installment in the Silent Hill series, the game was released in North America in January 1999, and in Japan and Europe later that year. Silent Hill uses a third-person view, with real-time rendering of 3D environments. To mitigate limitations of the console hardware, developers liberally used fog and darkness to muddle the graphics. Unlike earlier survival horror games that focused on protagonists with combat training, the player character of Silent Hill is an "everyman".[1]

The game follows Harry Mason as he searches for his missing adopted daughter in the eponymous fictional American town of Silent Hill; stumbling upon a cult conducting a ritual to revive a deity it worships, he discovers her true origin. Five game endings are possible, depending on actions taken by the player, including one joke ending.

Silent Hill received positive reviews from critics on its release and was commercially successful. It is considered a defining title in the survival horror genre, and is also considered by many to be one of the greatest video games ever made, as it moved away from B movie horror elements toward a more psychological horror style, emphasizing atmosphere.[1] Various adaptations of Silent Hill have been released, including a 2001 visual novel, the 2006 feature film Silent Hill, and a 2009 reimagining of the game, titled Silent Hill: Shattered Memories. The game was followed by Silent Hill 2 in 2001, and a direct sequel, Silent Hill 3, in 2003.

Gameplay

The objective of the player is to guide main protagonist and player character Harry Mason through a monster-filled town as he searches for his lost daughter, Cheryl. Silent Hill's gameplay consists of combat, exploration, and puzzle-solving.[3] The game uses a third-person view, with the camera occasionally switching to other angles for dramatic effect, in pre-scripted areas. This is a change from older survival horror games, which constantly shifted through a variety of camera angles. Because Silent Hill has no heads-up display, the player must consult a separate menu to check Harry's "health".[4] If a DualShock controller is used a heart beat rhythm can be felt signifying that the player is at low health.

Harry confronts monsters in each area with both melee weapons and firearms. An ordinary man, Harry cannot sustain many blows from enemies, and gasps for breath after sprinting.[2] His inexperience in handling firearms means that his aim, and therefore the player's targeting of enemies, is often unsteady.[5] A portable radio collected early in the game alerts Harry to the presence of nearby creatures with bursts of static.[2]

The player can locate and collect maps of each area, stylistically similar to tourist maps. Accessible from the menu and readable only when sufficient light is present, each map is marked with places of interest. Visibility is mostly low due to fog[3] and darkness; the latter is prevalent in the "Otherworld".[6] The player locates a pocket-size flashlight early in the game, but the light beam illuminates only a few feet.[2] Navigating through Silent Hill requires the player to find keys and solve puzzles.[3]

Plot

Silent Hill opens with Harry Mason driving to the titular town with his young daughter Cheryl for a vacation. At the town's edge, he swerves his car to avoid hitting a girl in the road; as a result, he crashes and loses consciousness.[5] Waking up in town, he realizes that his daughter is missing and sets out to look for her, finding the town deserted and foggy, with snow falling out of season.[7] During his journey, he begins to experience bouts of unconsciousness and nightmares filled with hostile creatures. He encounters police officer Cybil Bennett, who works in the nearby town of Brahms;[8][9][10] a fortune telling cultist, Dahlia Gillespie, who gives him a charm; the "Flauros" and hints at his daughter's whereabouts;[11] doctor Michael Kaufmann, director of Silent Hill's Alchemilla Hospital;[7][12] a nurse suffering from amnesia; Lisa Garland, who worked at Alchemilla.[12] He also encounters a symbol throughout the town, which Dahlia claims will allow darkness to take over the town if it continues to multiply.[7] Eventually, he realizes and explains to Cybil that this darkness is taking over the town, and is responsible for the disappearance of the citizens, and transforming it into someone's nightmare. According to Dahlia, the girl from the road is a demon responsible for the symbol's duplication. She urges him to stop the demon, because if he does not, Cheryl's life will be sacrificed to the demon. Dahlia urges Harry to stop the town from becoming a total apocalypse of demonic possession, by using the Flauros.[13] Harry soon finds himself attacked by Cybil, who has become possessed by the girl's power via parasite implant ;[14] the player must choose whether to save her or not.[15]

When Harry next encounters the form of the teenage girl, he demands to know where Cheryl is but is refused. Soon afterwards she is paralyzed by the Flauros that Harry was carrying. Dahlia appeared and revealed that she manipulated Harry into catching her daughter; Alessa, since only he could approach her apparently due to his connection with Cheryl and her reaching out to him. Alessa possesses vast reality warping powers to manifest objects into reality and used that power to previously escape a spell cast upon her by her mother to torture her within a nightmare forcing her to cry out for help from Cheryl. Together Dahlia & Alessa transport away using the Flauros.[16][17] Harry awakens in a logicless void known only as "nowhere" and encounters Lisa again, who realizes she is "the same as them"[18] and begins transforming; he flees, horrified. Her diary reveals that she nursed Alessa during a secret, forced hospitalization.[19] Harry soon finds Dahlia along with the apparition of Cheryl and Alessa, charred. Seven years earlier, Dahlia had conducted a ritual that impregnated Alessa with the cult's deity through immolation; Alessa survived because her status as the deity's "vessel" rendered her immortal.[16][20] Her resistance to the ritual caused her soul to be bisected, preventing the birth.[20][21][21] One half of her soul went to baby Cheryl, whom Harry and his wife had adopted.[17] Dahlia then cast a spell that would draw it back to Alessa.[21] Sensing Cheryl's return, Alessa manifested the symbols in the town to prevent her capture and likewise the birth. During the endings in which Cybil survives, Dahlia reveals these symbols to be repellent and protective by nature. With Alessa's plan thwarted and her soul rejoined, the deity is revived and possesses her.

Four different endings are available depending on whether Harry saves Cybil or discovers a bottle of Aglaophotis at Kaufmann's apartment, or both. Aglaophotis is a red liquid that is obtained from the refinement of a plant of the same name; it can dispel demonic forces and grant protection against such forces to those who use the item. The "bad" ending occurs if neither is done; Alessa electrocutes Dahlia and then attacks Harry, who ultimately defeats her. Cheryl's voice thanks Harry for freeing her and Alessa vanishes. Harry collapses, and the game cuts to his corpse in the crashed car - suggesting that all that happened in the game was a delusion of Harry's dying mind. The "bad +" ending finds Cybil alive and Kaufmann missing; after the echoing of Cheryl's voice and Alessa's disappearance, Cybil walks to Harry and convinces him to flee. The "good" ending finds Cybil dead, and Kaufmann shows up with the bottle of Aglaophotis which he then uses to force the deity out of Alessa;[15] Kaufmann is revealed to have secretly allied with Dahlia[19][20] and enabled Alessa's hospitalization. Feeling betrayed, he forces the deity out of Alessa, also causing her to vanish. After Harry defeats it, the deity disappears, and Alessa appears, who manifests a baby reincarnation of herself and Cheryl, gives it to Harry, enables their escape from the depths of "nowhere" and her nightmare, and then dies. In the "good +" ending, Harry escapes with Cybil and the baby. In both "good" endings, a transformed Lisa prevents Kaufmann from leaving and throws him into a pit.[15] The joke ending features extraterrestrials abducting Harry.[22]

Development

Design

.jpg)

Development of Silent Hill started in September 1996.[24] The game was created by Team Silent, a group of staff members within the Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo studio.[25][26][27] The new owners of its parent company Konami sought to produce a game that would be successful in the United States. For this reason, a Hollywood-like atmosphere was proposed for Silent Hill. The staff members that were assigned to the game's development had failed at their previous projects. They intended to leave Konami, as they were not allowed to realize their own ideas, and were not compatible with the company's other teams. According to composer Akira Yamaoka, the developers did not know how to proceed with the Silent Hill project, either. As the time passed, the personnel and management of Konami lost their faith in the game, and the members of Team Silent increasingly felt like outsiders. Despite the profit-oriented approach of the parent company, however, the developers of Silent Hill had much artistic freedom because the game was still produced as in the era of lower-budget 2D titles. Eventually, the development staff decided to ignore the limits of Konami's initial plan, and to make Silent Hill a game that would appeal to the emotions of players instead.[28]

For this purpose, the team introduced a "fear of the unknown" as a psychological type of horror. The plot was made vague and occasionally contradictory to leave its true meaning in the dark, and to make players reflect upon unexplained parts.[28] Director Keiichiro Toyama created the game's scenario,[29] while programmer Hiroyuki Owaku wrote the text for the riddles.[30][31] Toyama did not have much experience of horror movies but was interested in UFOs, the occult and David Lynch movies which influenced the game's development.[32] For this reason, Toyama questioned Konami's decision to appoint him as director, as he had never been one prior to Silent Hill.[33]

The localization company Latina International, which had previously worked on Final Fantasy VII, translated the script into English.[31][34] The town of Silent Hill is an interpretation of a small American community as imagined by the Japanese team. It was based on Western literature and films, as well as on depictions of American towns in European and Russian culture.[28] The game's joke ending came out of a suggestion box created to find alternative reasons for the occurrences in Silent Hill.[35]

Artist Takayoshi Sato corrected inconsistencies in the plot, and designed the game's cast of characters.[35] As a young employee, Sato was initially restricted to basic tasks such as font design and file sorting. He also created 3D demos and presentations, and taught older staff members the fundamentals of 3D modeling. However, he was not credited for this work as he did not have as much respect within Konami as older employees. Sato eventually approached the company's higher-ups with a short demo movie he had rendered, and threatened to withhold this technical knowledge from other staff members if he was not assigned to 3D work. As a consequence, his superior had to give in to his demand, and he was allowed to do character designs.[36] Instead of relying on illustrations, Sato conceived the characters of Silent Hill while creating their computer-generated models.[24][28] He gave each their own distinctive characteristics, but made Harry almost completely neutral as he wanted to avoid forcing interpretations of the game on the players.[28][35] Creating the skull shapes for the faces of the American cast was difficult because he had no Caucasian co-workers to use for reference.[35] Although Sato was largely responsible for the game's cinematics and characters at this point, his superior still did not want to fully credit his work, and intended to assign a visual supervisor to him. To prevent this from happening, Sato volunteered to create the full-motion videos of Silent Hill by himself.[36] Over the course of two and a half years, he lived in the development team's office, as he had to render the scenes with the approximately 150 Unix-based computers of his coworkers after they left work at the end of a day.[24][36]

Sato estimated the game's budget at US$3–5 million.[36] He said that the development team intended to make Silent Hill a masterpiece rather than a traditional sales-oriented game, and that they opted for an engaging story, which would persist over time – similar to successful literature.[28] The game debuted at the 1998 Electronic Entertainment Expo in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, where the presentations of movies and in-game scenes garnered applause from the audience.[36][37] This favorable reception persuaded Konami to allot more personnel and public relation initiatives to the project.[28] Konami later showcased Silent Hill at the European Computer Trade Show in London,[38] and included a demo with its stealth game Metal Gear Solid in Japan.[39]

The names and designs of some Silent Hill creatures and puzzles are based on books enjoyed by the character of Alessa, including The Lost World by Arthur Conan Doyle and Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[40][41] The game contains several real-life references, particularly in characters' names. Cheryl Mason's first name is based on actress Sheryl Lee's first name, and Lisa Garland's surname is taken from actress Judy Garland.[8] "Michael Kaufmann" is a combination of Troma Studios producers Michael Herz's and Lloyd Kaufmann's first name and surname, respectively. Alessa's original name was "Asia", and Dahlia's was "Daria", based on the first names of actresses Asia Argento and Daria Nicolodi – Argento's mother.[12] Harry's name was originally "Humbert", and Cheryl's was "Dolores", in reference to the protagonist and title character of Vladimir Nabokov's novel Lolita. The American staff altered these names, as they considered them too uncommon.[8] Fictitious religious items appearing in the game have used various religions as a basis: the evil spirit-dispelling substance Aglaophotis, which is said to be made from a medicinal herb, is based on a herb of similar name and nature in the Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism); the "Seal of Metatron" (also referred to by Dahlia as the "Mark of Samael") references the angels Metatron and Samael, respectively; and the name of the "Flauros"' was taken from the eponymous demon appearing in the Lemegeton, a book on magic said to have been compiled by writings of King Solomon.[42] Certain items and doors in the "nowhere" dimension of the game were given names based on occult elements in order to symbolize magical traits of Dahlia. The names of these doors were taken from the names of the angels Ophiel, Hagith, Phaleg, and Bethor, who appear in a medieval book of black magic and are supposed to rule over planets. This motif of giving names that suggest planets was used to signify that "a deeper part of the realm of Alessa's mind is being entered," according to Owaku.[41]

Music

The soundtrack for Silent Hill was composed by sound director Akira Yamaoka, who requested to join the development staff after the original musician had left.[23] In addition to the music, he was in charge of tasks such as sound effect creation and audio mastering.[23][31][43] Yamaoka did not watch game scenes, but created the music independently from its visuals. The style of his compositions was influenced by Twin Peaks composer Angelo Badalamenti.[44] To differentiate Silent Hill from other games as much as possible, and to give it a cold and rusty feel, Yamaoka opted for industrial music.[23] When he presented his musical pieces to the other staff members for the first time, they misinterpreted their sound as a game bug. Yamaoka had to explain that this noise was intended for the music, and the team only withdrew their initial objection after he elaborated on his reasons for choosing this style.[28]

On March 5, 1999, the album Silent Hill Original Soundtracks was released in Japan. The 41st track on the CD, the ending theme "Esperándote", was composed by Rika Muranaka. After Yamaoka had approached her to create a piece of music for the game, she suggested the use of bandoneóns, violins, and a Spanish-speaking singer. It was decided to make the song a tango, and Muranaka composed the melody for the English lyrics she had conceived.[43] When she arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to record the translated Spanish lyrics with Argentine singer Vanesa Quiroz, Muranaka realized that the syllables did not match the melodic line any more, and she had to recompose it in five minutes.[31][43]

On October 29, 2013, Perseverance Records released a "Best Of" album, which features 16 newly interpreted instrumental tracks composed by Akira Yamaoka and arranged and performed by Edgar Rothermich.[45] The 17th track on the album is the ballad "I Want Love" performed by Romina Arena.

Release

Silent Hill was released for the PlayStation in North America on January 31, 1999; in Japan on March 4, 1999; and in Europe on August 1, 1999.[46] It was included in the Japanese Silent Hill Complete Set in 2006.[47] On March 19, 2009, Silent Hill became available for download from the European PlayStation Network store of the PlayStation 3 and the PlayStation Portable.[48] Two days later, the game was removed due to "unforeseen circumstances".[49] On September 10, 2009, Silent Hill was released on the North American PlayStation Network.[50] On October 26, 2011 it was re-released on the European PlayStation Network.[51]

Adaptations

A radically altered version of Silent Hill was released for the Game Boy Advance. Titled Play Novel: Silent Hill and released only in Japan in 2001, it is a gamebook-style visual novel. It contains a retelling of Silent Hill's story through text-based gameplay, with the player occasionally confronted with questions concerning what direction to take the character, as well as the puzzles, which are a major part of Silent Hill's gameplay. After completing the game once, the player has the option of playing as Cybil in a second scenario, with a third made available for download once the second scenario has been completed.[52] When the game was exhibited, Western critics were unimpressed, and criticized the lack of any soundtrack as severely detracting from the "horror" factor of the game.[52][53]

A film adaptation, also titled Silent Hill, was released on April 21, 2006. The film, directed by Christophe Gans, was based largely but loosely on the game, incorporating elements from Silent Hill 2, 3, and 4.[54][55] Gans replaced Harry Mason with a female main protagonist, Rose Da Silva, because he felt Harry had many qualities typically perceived as feminine.[56] When designing the film's visual elements, Gans was influenced by fellow directors Michael Mann, David Lynch, and David Cronenberg.[57] The film's soundtrack includes music composed by Yamaoka.[58] Although critical reaction was mostly negative, the film was a financial success and was praised by fans, especially for its visuals.[59][60]

A "reimagining" of Silent Hill, titled Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, was developed by Climax Studios and published by Konami Digital Entertainment. The game was released on December 8, 2009, for the Wii and on January 19, 2010, for the PlayStation 2 and the PlayStation Portable, to mostly positive reviews.[61] Although it retains the premise of a man's search for his missing daughter, Shattered Memories branches off into a different plot with altered characters.[62] It features psychological profiling which alters various in-game elements depending on the player's response to questions in therapy,[62] lacks the combat of Silent Hill, and replaces the "Otherworld" with a series of chase sequences through an alternate frozen version of the town.[62]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Silent Hill received generally positive reviews, gaining an 86/100 aggregate at ratings website Metacritic, respectively.[63] The game sold over two million copies,[24] which gained Silent Hill a place in the American PlayStation Greatest Hits budget releases.[68]

Silent Hill has been compared to the Resident Evil series of survival horror video games. Bobba Fatt of GamePro labeled Silent Hill a "shameless but slick Resident Evil clone",[4] while Edge described it as "a near-perfect sim nightmare."[64] Others felt that Silent Hill was Konami's answer to the Resident Evil series[5] in that, while they noted a similarity, Silent Hill utilized a different form of horror to induce fear, attempting to form a disturbing atmosphere for the player, in contrast to the visceral scares and action-oriented approach of Resident Evil.[3] Adding to the atmosphere was the audio, which was well-received; Billy Matjiunis of TVG described the ambient music as "engrossing";[69] a reviewer for Game Revolution also praised the audio, commenting that the sound and music "will set you on edge".[3] Less well-received was the voice acting which, although some reviewers remarked it was better than that found in the Resident Evil series,[4] was found poor overall by reviewers, and accompanied by pauses between lines that served to spoil the atmosphere.[3][4]

Reviewers noted that Silent Hill used real-time 3D environments, in contrast to the pre-rendered environments found in Resident Evil. Fog and darkness were heavily used to disguise the limitations of the hardware.[2][4] Along with the grainy textures—also from hardware limitations[2][5]—most reviewers felt that these factors actually worked in the game's favor; Francesca Reyes of IGN described it as "adding to the atmosphere of dilapidation and decay".[5] In using 3D environments, however, controls became an issue, and in "tougher" areas, maneuverability became "an exercise in frustration".[5]

The game's popularity as the first in the series was further recognized long after its release; a list of the best PS games of all time by IGN in 2000 listed it as the 14th-best PS game,[70] while a 2005 article by GameSpy detailing the best PS games listed Silent Hill as the 15th-best game produced for the console.[37] A GameTrailers video feature in 2006 ranked Silent Hill as number one in its list of the top ten scariest games of all time.[71] In 2005, the game was credited for moving the survival horror genre away from B movie horror elements to the psychological style seen in art house or Japanese horror films,[72] due to the game's emphasis on a disturbing atmosphere rather than visceral horror.[3] In November 2012, Time named it one of the 100 greatest video games of all time.[73]

Notes

- ↑ Silent Hill (サイレントヒル Sairento Hiru)

References

- 1 2 Fahs, Travis. "IGN Presents the History of Survival Horror". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fielder, Joe (1999-02-23). "Silent Hill Review for PlayStation". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Baldric (1999-03-01). "Silent Hill Review for the PS". Game Revolution. AtomicOnline, LLC. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fatt, Bobba (2000-11-24). "Silent Hill Review". GamePro. GamePro Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-12-27. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reyes, Francesca (1999-02-24). "Silent Hill – PlayStation Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-09-29. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc.

Harry: It's not me. This whole town... it's being invaded by the Otherworld. A world of someone's nightmarish delusions come to life. Little by little, the invasion is spreading. Trying to swallow up everything in darkness. I think I'm finally beginning to understand what that lady was talking about.

- 1 2 3 Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Alchemilla Hospital.

- 1 2 3 "Silent Hill Character Commentary". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 24. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Cafe 5 to 2.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Beginning/North Bachman Road.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Balkan Church.

- 1 2 3 "Silent Hill Character Commentary". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 25. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Lake View Pier Boat.

- ↑ "XII: The Hanged Man – Douglas Cartland". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 99. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 3 "Silent Hill Ending Analysis". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. pp. 28–29. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 "III: The Empress – Alessa". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 88. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Lakeside Amusement Park.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Alchemilla Hospital (Nowhere).

- 1 2 "Alessa's History". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 8. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 3 "Silent Hill Series – Characters Relation Map". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. pp. 10–11. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 3 Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: Nowhere.

- ↑ Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. PlayStation. Konami of America, Inc. Level/area: UFO Ending.

- 1 2 3 4 Kalabakov, Daniel (2002-07-16). "Interview with Akira Yamaoka". Spelmusik.net. Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Sato, Takayoshi. "My Resume". SatoWorks. Archived from the original on 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ↑ ゲームソフト プレイステーション (in Japanese). Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc. Archived from the original on 2004-10-12.

- ↑ "E3 2001: Silent Hill 2 Interview". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 2001-05-17. Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- ↑ "IGN Top 100 Games 2007 – 97: Silent Hill 2". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Villner, Pär (March 2008). "Mörkerseende". Level (in Swedish). Reset Media AB (23): 85–93.

- ↑ クリエイターズファイル 第127回 (in Japanese). Gpara.com. 2003-11-04. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ↑ Ito, Masahiro (2010-06-14). "Nobu bbs: scenario writers". GMO Media, Inc. Archived from the original on August 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

The first SILENT HILL is Keiichiro Toyama's original scenario. But Hiroyuki Owaku had charge of that riddle part.

- 1 2 3 4 Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, Inc (1999-01-31). Silent Hill. Konami of America, Inc. Scene: staff credits.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-14. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑ Toyama, Keiichiro. "Silent Hill". Twitter. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ 制作物 (in Japanese). Latina International Corporation. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Dieubussy (2009-05-15). "Interview with Takayoshi Sato: Seizing New Creations". Core Gamers. Archived from the original on 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sheffield, Brandon (2005-08-25). "Silence Is Golden: Takayoshi Sato's Occidental Journey". Gamasutra. United Business Media LLC. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- 1 2 Williams, Bryn; Vasconcellos, Eduardo (2005-09-07). "Top 25 PSone Games of All-Time". GameSpy. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ "ECTS: Konami Gears Up". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 1998-09-08. Archived from the original on 2007-09-01. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ "Metal Gear to Arrive Demo-less". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 1998-09-04. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Silent Hill Creature Commentary". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. pp. 26–27. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 "XVII: The Star – Motif". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. pp. 106–107. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- ↑ "V: The Hierophant - Key Items". Silent Hill 3 公式完全攻略ガイド/失われた記憶 サイレントヒル・クロニクル [Silent Hill 3 Official Strategy Guide / Lost Memories: Silent Hill Chronicle] (in Japanese). NTT Publishing Co., Ltd. 2003-07-31. p. 91. ISBN 4-7571-8145-0.

- 1 2 3 Silent Hill Original Soundtracks (Media notes). Konami Co., Ltd. 1999. KICA-7950.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-26. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ↑ "Silent Hill for PlayStation". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Fricke, Nicholas (2006-08-03). "A look inside the Silent Hill Complete set". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Plunkett, Luke (2009-03-20). "PAL PlayStation Store Update: Silent Hill!". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ "Official PlayStation Community". Sony Computer Entertainment Europe. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

We have unfortunately had to remove Silent Hill from the PlayStation Store due to unforeseen circumstances.

- ↑ Sliwinski, Alexander (2009-09-10). "PSN Thursday: In time with Turtles, Silent Hill and George Takei". Joystiq. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-03-12. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ Michael Harradence (2011-10-26). "European PSN update; October 26, 2011". PlayStation Universe. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- 1 2 "Silent Hill Play Novel – Game Boy Advance Preview". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 2001-01-19. Archived from the original on 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Lake, Max (2001-01-10). "Play Novel: Silent Hill Preview". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Otto, Jeff (2006-03-10). "Silent Hill: Director Interview & Exclusive Image". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Gans, Christophe (2006-03-10). "On Preserving and Contributing to the Mythology of the Games". Sony Pictures Digital Inc. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ↑ Gans, Christophe (2006-03-06). "On Harry Mason, the WonderCon Footage, and Capturing the Horror of the Game". Sony Pictures Digital Inc. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ↑ Otto, Jeff (2006-03-10). "Silent Hill: Director Interview & Exclusive Image". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ↑ Otto, Jeff (2006-03-10). "Silent Hill: Director Interview & Exclusive Image". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ↑ "Silent Hill Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More". Metacritic. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ "Silent Hill Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-10-27. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Magrino, Tom (2009-04-06). "Silent Hill: Shattered Memories confirmed for fall". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- 1 2 3 Turi, Tim (2009-12-08). "Silent Hill: Shattered Memories Review". Game Informer. Game Informer Magazine. Archived from the original on 2010-05-17. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- 1 2 "Silent Hill for PlayStation Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-11-26. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- 1 2 "Silent Hill". Edge. No. 70. Future Publishing. April 1999. pp. 72–73.

- ↑ プレイステーション - SILENT HILL. Weekly Famitsu. No.915 Pt.2. Pg.6. 30 June 2006.

- ↑ Official PlayStation Magazine, Future Publishing issue 48, (July 1999)

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/PSX_Magazine_32#page/n55/mode/2up

- ↑ "Silent Hill (Greatest Hits)". Konami Digital Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ↑ Matjiunis, Billy. "Silent Hill Review". TVG. TVG Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 2008-12-24. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Perry, Douglass C.; Zdyrko, Dave; Smith, David (2000-06-07). "Top 25 Games of All Time: #11–15". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ "Top Ten Scariest Games". GameTrailers. MTV Networks. 2006-10-27. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Hand, Richard J. (2004). "Proliferating Horrors: Survival Horror and the Resident Evil Franchise". In Hantke, Steffen. Horror Film: creating and marketing fear. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 117–134. ISBN 1-57806-692-1.

- ↑ "All-TIME 100 Video Games". Time. Time Inc. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

External links

- Official website (in Japanese)

- Takayoshi Sato official website