Siege of Almería (1309)

The Siege of Almería was an unsuccessful attempt by Aragon to capture the city of Almería from the Emirate of Granada in 1309. The city defenders repelled multiple assaults, and by the end of December James II of Aragon, who personally led the siege, asked for a truce and subsequently withdrew from Granadan territory.

Background

Muhammad III of Granada made peace with Castile in the 1303 treaty of Córdoba and became a vassal of Ferdinand IV of Castile. Aragon made peace with Castile in the 1304 Treaty of Torellas, which also included peace with Granada as Castile's vassal.[1] Peace achieved with the Spanish powers, Granada turned its attention to North Africa. Taking advantage of the war between the Marinids and the Kingdom of Tlemcen, Muhammad instigated a rebellion in Ceuta—a port town just across the Strait of Gibraltar—against the Marinids in 1304, and in 1306 he sent a fleet to capture the town from the rebels.[2]

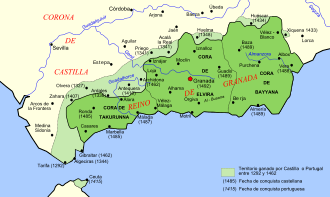

With Ceuta in its hands, Granada now controlled both sides of the strait—it held the ports of Gibraltar and Algeciras on the European side.[3] This development worried Aragon and Castile, and they began to make plans against Granada.[3] They signed the Treaty of Alcalá de Henares on 19 December 1308, pledging to help each other conquer Granada and split its territories between them.[3] Aragon was promised a sixth of Granadan territories, including the port town of Almería, and the rest would go to Castile.[3] In addition, both Christian powers also made an alliance with Abu al-Rabi Sulayman, who became the Sultan of the Marinids in July 1308 and wanted to recover Ceuta.[3][4] The end result was a tripartite alliance of Castile, Aragon and the Marinids against Granada, which was now isolated and surrounded by three larger enemies.[4]

Preparation

To wage war against Granada, James II raised an army with the planned total of 12,000 including 1,000 knights and 2,000 archers.[5] He also raised funds and strengthened the defenses of the Kingdom of Valencia.[5] Almería was located in the southeastern coast of the Emirate of Granada.[5] Aragon did not have an immediate border with Granada, so a part of the force was transported by sea and others had to march overland through Castilian territories and then from the Castile–Granada frontiers to Almería via hostile territories.[5]

The city of Almería prepared against a siege by stockpiling food, implementing a ration and strengthening the city's defenses.[5][6] A Muslim account emphasized the importance of the food supplies, saying that "One of the signs of God's protection of the city's inhabitants was that great quantities of barley were in the storehouses at the beginning of the siege".[6] The city's governor, Abu Maydan Shuayb and the naval commander Abu al-Hasan al-Randahi organized the improvement of the city's defense.[6] They strengthened the walls, closed various gaps and demolished outer buildings that might be used by the attackers.[6]

Siege

James II and his forces sailed from Valencia on 18 July 1309 and landed on the coast of Almería in mid-August.[5] A Muslim account emphasized the forces' rich and colorful clothing, and the military instruments played by their musicians.[5][7] His forces included siege machines such as mangonels and trebuchets.[5] Such a display initially demoralized the defenders, but as time went by and various incidents took place, they became more optimistic.[5][7]

The besiegers blockaded the city by land and sea, and established palisades and ditches.[5] However, the late summer arrival was a major disadvantage for the invaders.[7] It meant that there was a short time before the weather got cooler, and if the siege lasted until winter it would be an advantage for the defenders who did not have to be out in the field.[7]

On 23 August, the besiegers won a battle in the open field.[5] A Christian account mentioned that the Muslims lost 6,000 men, but modern historian Joseph F. O'Callaghan considered this figure to be clearly exaggerated.[5] Upon hearing the news, Pope Clement V congratulated James on the victory.[5]

In late August or early September, the city defenders repelled an assault by the Aragonese forces.[lower-alpha 1] [7][8] The attackers used scaling ladders and siege towers which were loaded with troops and moved by wheels.[8][7] The defenders resisted by pouring boiling oil and other flammables, forcing the assault to be aborted.[8] During the retreat, many were left behind and captured by the Muslims.[7] After this failure, the besiegers continued to lob rocks weighing up to thirty pounds into the city, claiming to kill 22,000 inhabitants.[8]

On 17 September a contingent sent from Granada under Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula arrived in the nearby Marchena and defeated a small Aragonese force.[8] This relief contingent camped in Marchena and would continuously frustrate the besiegers by harassing their foraging parties.[8][7] As the siege continued, the invaders tried to use a stratagem to trick the defenders.[7] A group of Christian soldiers slipped out in the darkness and then approached the city dressed as Muslims.[7] A group of Christian knights then pretended to give them a chase and to leave their tents unguarded.[7] The tents were made to look as a tempting target for pillage while in fact the tents were set up for an ambush.[9] A group of riders then came out of the city to pillage the tents, but the Christians came out of the ambushes too soon, allowing the Muslims to escape.[9] Most of the Muslims managed to reenter the city via the side entrance that happened to be made ready to open the day before, but some were left behind.[9] They then had to stay at the foot of the walls, protected by covering fire from the city. When the fighting died down they managed to reenter the city.[9]

The siege's progress was dominated by the exchange of shots from siege engines.[10] According to Ibn Al-Qadi 22,000 rocks were thrown throughout the siege.[10] The attackers had eleven catapults or other such engines.[10] The Muslims initially had just one, but when this was destroyed by enemy fire they built three more.[10] At the end of December, a section of the walls was breached and the Christians rushed to attack it, but a Muslim force defended the section and stopped them from entering the city.[lower-alpha 2][11][8]

Truce and Christian withdrawal

At this point the prospect for a Christian victory faded. Winter was coming and would endanger their forces in the field.[10] The concurrent Siege of Algeciras by Castile was weakening and allowed Granada to deploy more forces against Aragon.[10] In addition, winds blew from the west and prevented the besiegers from receiving supplies which came by sea from Aragon.[8] At the end of December, a parley took place in the Aragonese camp, and both sides agreed to a truce.[10]

According to the truce, the Aragonese were to withdraw from Granadan territories. Due to the logistical difficulties, such as lack of vessels to bring the troops home, evacuation took place gradually and those not yet evacuated were left under Muslim protection. The evacuation ended in early 1310.[12]

Aftermath

The repulsion of the Aragonese from Almería, as well as the nearly simultaneous defense of Algeciras from Castile, were major successes for Granada. Both Castile and Aragon made peace with Granada by early 1310. According to the historian L. P. Harvey, the particularly humiliating defeat and evacuation of the Aragonese "taught [the Aragonese] a lesson" and delayed the progress of the reconquista for decades.[13]

References

Notes

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 175 dated the assault at 21 Rabi al-Awwal 709 AH, circa 29 August, while O'Callaghan 2011, p. 132 says "early September"

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 176 dated this breach at 22 Rajab 709 H, about 26 December, while O'Callaghan 2011, p. 132 says 5 January, which is confusing because both sources say that a truce was agreed at the end of December and stopped the assault of the city.

Citations

- ↑ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Callaghan 2011, p. 122.

- 1 2 Harvey 1992, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 O'Callaghan 2011, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 Harvey 1992, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Harvey 1992, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 O'Callaghan 2011, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Harvey 1992, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Harvey 1992, p. 178.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 176–167.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Harvey 1992, p. 179.

Bibliography

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (17 March 2011). The Gibraltar Crusade: Castile and the Battle for the Strait. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-0463-8.