Severn Railway Bridge

| Severn Railway Bridge | |

|---|---|

Severn Railway Bridge in July 1948 | |

| Coordinates | 51°43′58″N 2°28′26″W / 51.7327°N 2.474°WCoordinates: 51°43′58″N 2°28′26″W / 51.7327°N 2.474°W |

| Crosses | River Severn |

| Locale | Lydney – Sharpness |

| Preceded by | Severn Tunnel |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 4,162 feet (1,269 m) |

| Clearance above | 70 feet (21 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | George Baker Keeling |

| Construction start | 1875 |

| Construction end | 1879 |

| Collapsed | 25 October 1960 |

| Severn Bridge Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

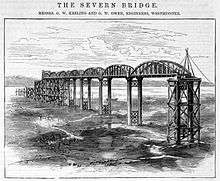

The Severn Railway Bridge (historically called the Severn Bridge) was a bridge carrying the railway across the River Severn between Sharpness and Lydney, Gloucestershire. It was built in the 1870s by the Severn Bridge Railway Company, primarily to carry coal from the Forest of Dean to the docks at Sharpness; at that time it was the furthest downstream bridge over the Severn. When the company got into financial difficulties in 1893, it was taken over jointly by the Great Western Railway and the Midland Railway companies. The bridge continued to be used for freight and passenger services until 1960, and saw temporary extra traffic on the occasions that the Severn Tunnel was closed for engineering work.

The bridge was constructed by Hamilston's Windsor Ironworks Company Limited of Garston, Liverpool. It was approached from the north via a masonry viaduct and had twenty-two spans. The pier columns were formed of circular sections, bolted together and filled with concrete. The twenty-one regular wrought iron spans were then put in place, as well as the southernmost span, the swinging bridge over the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal. The bridge was 4,162 ft (1,269 m) long and 70 ft (21 m) above high water, a total of 6,800 long tons (7,600 short tons; 6,900 t) of iron being used in its construction.

A number of accidents took place at the bridge over the years, with vessels colliding with the piers, due to the hazardous nature of the waterway. In 1960, two river barges hit one of the piers on the bridge, causing two spans to collapse into the river. Repair work was under consideration when a similar collision occurred the following year, after which it was decided that it would be uneconomical to repair the bridge. It was demolished between 1967 and 1970, with few traces remaining.

Construction

For more than fifty years before the Severn Railway Bridge was opened, there had been discussion and various proposals for rail routes to cross the Severn, either by a bridge or a tunnel, but most of these did not leave the drawing board. The exception was a tunnel near Newnham-on-Severn in 1810; this had been excavated part-way under the river when water broke in, and the tunnellers were lucky to escape with their lives. The damage was irreparable and the project abandoned.[1] In 1845, an ambitious project by Isambard Kingdom Brunel was to bridge the Severn near Awre for his projected South Wales Railway, bypassing Gloucester completely. This plan got as far as receiving the approval of Parliament but did not proceed. Other schemes were mooted and in 1871, six different schemes were under consideration.[2] Finally the Severn Bridge Railway's scheme was approved by Parliament and received Royal Assent on 18 July 1872.[3]

The Severn Railway Bridge was built by the Severn Bridge Railway Company to transport coal from the Forest of Dean on the Severn and Wye Railway. At the time it was expected that the amount of coal freighted would increase year by year and the existence of a bridge would remove the necessity for the coal to be shipped via Gloucester.[4] Work began in 1875[5] and was completed in 1879;[6] the wrought iron bridge, which was 4,162 feet (1,270 m) long and 70 feet (21 m) above high water, had twenty-two spans and had stone abutments made from local limestone. The first span across the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal, which ran parallel to the Severn at this point, operated as a swing bridge.[5] The twenty-one fixed spans, in order of erection from the south-east (Sharpness) side, consisted of 13 of length 134 ft (41 m), 5 of length 174 ft (53 m), 2 of length 312 ft (95 m), and a single span of length 134 ft (41 m).[7] The bridge incorporated 6,800 long tons (7,600 short tons; 6,900 t) of iron. It was approached from the south-east by a two-arch masonry viaduct on the canal embankment leading to the swing-bridge, and on the north-west by a 12-arch viaduct about 70 ft (21 m) high.[8]

The river with its large tidal range and strong currents made construction difficult. The pier columns were formed of 4 ft (1.2 m) cylindrical sections, about 10 ft (3.0 m) in diameter. Near the west bank, the bedrock was a long way below the shifting sands so much work had to prepare firm foundations. Staging was used through which the sections were lowered by chains, and when in place, filled with concrete. Near the east bank, a primitive piling machine was used to drive the sections through a ridge of clay. The staging was extended upwards for use while assembling the spans.[9][10]

The spans were assembled on site. Staging was laid and rails put in place to carry a travelling crane. The long beams were hoisted in place first, followed by the vertical bracings, and then the outer and inner plates of the top chordal trusses and the diagonals. The whole structure was bolted together at first, and later riveted by blacksmiths using hand-operated forges. Some individual spans were completed within a week, with contractors being complimented on the efficiency of their work.[11]

The main contractor was Hamilston's Windsor Ironworks Company Limited of Garston, Liverpool. They were tasked with the founding and erection of the pier cylinders on the riverbed, and the erection and riveting of the twenty-one bowstring spans and the swing bridge over the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal. They were also responsible for another swing bridge on the North Docks Branch of the line close to the New Docks at Sharpness. The company manufactured the castings and the wrought iron structures for the bridge. Project manager George Earle was later given a watch praising his ability and enthusiasm for carrying out the project.[12] The engineers for the project were George Wells Owen and George William Keeling.[13]

History

The bridge carried a single track railway line. When it came into service, it took approximately 30 miles (48 km) off the journey from Bristol to Cardiff, with trains no longer having to pass through Gloucester. The bridge predated the construction of the Severn Tunnel, a dozen miles or so downstream, by seven years. The opening ceremony for the bridge took place on 17 October 1879; nearly four hundred dignitaries travelled in twenty-three first class carriages across the bridge and back again, with fog signals exploding on each of the spans during the return trip. A banquet followed at the Pleasure Grounds near Sharpness station.[14]

During construction, it was anticipated that the Severn Bridge Railway would mainly receive its revenue from carrying coal from the Forest of Dean.[15] However, the Severn Bridge Railway Company ran into financial difficulties as coal was not carried in the volumes that had been anticipated, nor had tourist travel risen to the expected levels. Miners in the Forest of Dean went on strike about low pay and poor conditions and the coal trade there continued to be depressed. The opening of the Severn Tunnel, providing an alternative route from England into South Wales, was a serious blow to the bridge. By 1890, the company was unable to pay the interest on its debentures and faced bankruptcy. As a result, it was taken over jointly by the Great Western Railway and the Midland Railway in 1893, becoming the Severn and Wye Joint Railway.[16]

Several fatalities occurred during the construction of the bridge. A baulk of timber fell on one man when a rope slipped, and another died when he fell from the part-completed structure, injuring himself on the staging as he fell. Only a few days after the bridge's opening, a rowing boat trying to pass underneath was caught in a giant eddy and capsized, one occupant being drowned.[17] Over the succeeding years a number of accidents have happened at the bridge involving larger vessels. The trow Brothers was lost after a collision with one of the piers in 1879, and the Victoria, employed in the bridge's construction, was wrecked in the 1880s. In 1938, a tug and two barges got into difficulties and were carried along broadside by the tide into the bridge; a connecting hawser snagged one of the piers and the vessels capsized, with several fatalities.[18]

Until the Severn Road Bridge was opened in 1966, the Severn Railway Bridge was often referred to as the Severn Bridge. There was a small station known as Severn Bridge on the Lydney side, adjacent to the Gloucester to Newport Line, which the Severn Bridge Line crossed over.[19] The bridge was used as a diversionary route for passenger services when the Severn Tunnel was closed for engineering work. The south-to-north chord at Berkeley Loop South Junction used for this route was closed when the bridge was abandoned. The remaining line from Berkeley Rd Junction to Sharpness Docks remains and on the north side of the Severn estuary, the line from the former Otters Pool Junction at Lydney to the Severn Bridge has long been lifted but a short section of the track exists as part of the Forest of Dean Railway network.[20]

In 1943, a flight of three Spitfires was being delivered by ATA pilots, including one woman, Ann Wood, from their factory in Castle Bromwich to Whitchurch, Bristol. As it was low tide, the lead pilot Johnnie Jordan flew under the bridge. Some time later, Ann Wood repeated this under-flying – without realising that this time it was high tide and there was 30 ft (9 m) less headroom but she just squeezed through.[21] These were not the only instances of pilots buzzing the bridge, and on one occasion a Vickers Wellington, a much larger aircraft, was seen to fly under it. The practice became so common that RAF police were called in and tasked with the recording of serial numbers of offending aircraft. After a few courts-martial, the incidents ceased.[22]

1960 accident

On 25 October 1960, in thick fog and a strong tide, two barges (named the Arkendale H and Wastdale H) which had overshot Sharpness Dock, collided with one of the columns of the bridge after being carried upstream.[9] Two bridge spans collapsed into the river.[9] As they fell, parts of the structure hit the barges causing the fuel oil and petroleum they were carrying to catch fire. Five people died in the incident.[9]

Local people favoured repairing the bridge as schoolchildren, who had used the bridge daily, now had to be taken on a 40-mile (64 km) detour via Gloucester. An underwater survey in December 1961 found extensive damage to Pier 16. Rebuilding costs were estimated to be £312,000 as against dismantling costs of £250,000. The Western Region of British Railways planned to go ahead with reconstruction but shortly before the work was due to start, a capsized tanker caused further damage to Pier 20, and this same pier was struck again when the contractor's crane broke adrift. These accidents added a further £20,000 to the estimated costs of repair, and in 1965, British Rail decided that the bridge was damaged beyond economic repair and opted for demolition.[9]

Demolition

Demolition began in August 1967. The contract was awarded to Nordman Construction after an unsuccessful tender process.[23][24] The company brought in the Magnus II, a floating crane with a lifting capacity of 400 long tons (450 short tons; 410 t), which could remove all but two of the spans. These longer spans were pulled sideways off the piers, expecting that they would break into manageable pieces under their own weight. They proved stronger than this and remained intact, needing to be broken up in the river, with much sinking into the bed instead of being recovered.[25]

In May 1968, another firm, Swinnerton & Miller, completed the main demolition work with the help of explosives, but clearing of the debris took another two years.[9]

Evidence of several of the piers remains. The most significant is a large circular tower, sited between the canal and river. This had formed the base of the swinging section and housed the steam engine to power it.[9] A large stone arch also remains on the landward side of the canal, the original abutment to the swinging section. Some piers are reduced to the stone foundations and only visible at low tide, as are the wrecks of the petrol barges that caused the original damage. The river at this point has always been hazardous to shipping because of the strong tidal currents, which caused the 1960 collision.

During the demolition, a support vessel the Severn King (an old Aust Ferry boat that had become surplus after the new Severn road bridge opened and the ferry closed) broke its mooring in the tide, grounded on the remains of the bridge and flooded.[26]

A wooden motor barge, the Halfren of 1913,[27] was also used in the demolition work, for collecting small pieces of wreckage. Worn out by this work and the frequent groundings, it was abandoned on the shore at Aust.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 1.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 6–14.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 23.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Patrick Stephens Limited. 1990. pp. 234–236. ISBN 978-1-85260-049-5.

- 1 2 Paget-Tomlinson, Edward (2006). The Illustrated History of Canal & River Navigations 3rd edition. Landmark Publishing Ltd. pp. 124–125. ISBN 1-84306-207-0.

- ↑ Vivian, Andy (20 October 2010). "Remembering the Severn Rail Bridge disaster". BBC Gloucestershire. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 114.

- ↑ "Engraving of the Severn Railway Bridge". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lost in the Fog". Bridges and Viaducts. Forgotten Relics of an Enterprising Age. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 36.

- ↑ "Hamilton's Windsor Ironworks Co". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ "Severn Railway Bridge". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 107.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 51–55.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 119.

- ↑ "Victoria County History of Gloucestershire: Lydney". A P Baggs and A R J Jurica, 'Awre', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 5, Bledisloe Hundred, St. Briavels Hundred, the Forest of Dean, ed. C R J Currie and N M Herbert (London, 1996), pp. 14-46. British History Online. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 150.

- ↑ Whittell, Giles (2007). Spitfire Women of World War II. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-723536-4.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 127.

- ↑ Biddle, Gordon (2003). Britain's Historic Railway Buildings. Oxford University Press. p. 299, "Purton". ISBN 0-19-866247-5.

- ↑ Jordan (1977), p. 91.

- ↑ Huxley (1984), p. 146.

- ↑ "The Steamboat Builders of Brimscombe" (PDF). Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology: 3–20. 1988.

- ↑ Jordan (1977), p. 96.

Bibliography

Further reading

- Maggs, C. G. (1959). Allen, G. Freeman, ed. The Severn Bridge, in Trains Illustrated Annual 1959. Hampton Court, Surrey: Ian Allan Ltd.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Severn Railway Bridge. |

- Andy Vivian (20 October 2010), The Severn Rail Bridge Disaster remembered, BBC Radio Gloucestershire

- In pictures: The Severn Rail Bridge Disaster, BBC Gloucestershire

- Severn Bridge disaster 'explained' 50 years on, BBC Gloucestershire, 20 October 2010

- The Severn Rail Bridge Disaster, BBC Gloucestershire, 26 October 2004, archived from the original on 8 April 2005