Seven Sisters (colleges)

The Seven Sisters was a name given to seven liberal arts colleges in the Northeastern United States that are historically women's colleges. Five of the seven institutions continue to offer all-female undergraduate programs: Barnard College, Bryn Mawr College, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College, and Wellesley College. Vassar College has been co-educational since 1969. Radcliffe College shared common and overlapping history with Harvard College from the time it was founded as "the Harvard Annex" in 1879. Harvard and Radcliffe effectively merged in 1977, but Radcliffe continued to be the sponsoring college for women at Harvard until its dissolution in 1999. Barnard College was Columbia University's women's liberal arts undergraduate college until its all-male coordinate school Columbia College went co-ed in 1983; to this day, Barnard continues to be an all-women's undergraduate college affiliated with Columbia.

All seven schools were founded between 1837 and 1889. Four are in Massachusetts, two are in New York, and one is in Pennsylvania.

Seven Sisters colleges

History

Background

Irene Harwarth, Mindi Maline, and Elizabeth DeBra note that "Independent nonprofit women’s colleges, which included the 'Seven Sisters', were founded to provide educational opportunities to women equal to those available to men and were geared toward women who wanted to study the liberal arts".[1] The colleges also offered broader opportunities in academia to women, hiring many female faculty members and administrators.

Early proponents of education for women were Sarah Pierce (Litchfield Female Academy, 1792); Catharine Beecher (Hartford Female Seminary, 1823); Zilpah P. Grant Banister (Ipswich Female Seminary, 1828); and Mary Lyon. Lyon was involved in the development of both Hartford Female Seminary and Ipswich Female Seminary. She was also involved in the creation of Wheaton Female Seminary (now Wheaton College, Massachusetts) in 1834. In 1837, Lyon founded Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (Mount Holyoke College).[2] Mount Holyoke received its collegiate charter in 1888 and became Mount Holyoke Seminary and College. It became Mount Holyoke College in 1893. Vassar, however, was the first of the Seven Sisters to be chartered as a college in 1861.

Wellesley College was chartered in 1870 as the Wellesley Female Seminary, and was renamed Wellesley College in 1873. It opened to students in 1875. Smith College was chartered in 1871 and opened its doors in 1875. Bryn Mawr opened in 1885.

Radcliffe College grew out of the Women’s Education Association of Boston, founded by a group of influential women, including Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, whose late husband was a famous Harvard scientist. Radcliffe College was founded in 1879 and chartered by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1894. It was informally called The Harvard Annex[3]because Harvard Professors repeated the lectures they'd given to male Harvard students there until 1943. By 1946, the majority of Harvard College courses were offered to both female Radcliffe students and male Harvard Students. The schools further integrated in the 1960's, and in 1963 the first Harvard degrees were conferred on Radcliffe women. Despite having joint admissions, Women's degrees would continue to bear both Harvard and Radcliffe seals until 1999, when the merger of the two schools was completed. Since 1999, all undergraduate students have received diplomas bearing the seal of Harvard College, and identified as Harvard students. [4] Radcliffe College no longer exists as an undergraduate institution, but Radcliffe class reunions take place at Harvard each year. The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study was created following the merger in 1999, and today offers non-degree instruction and executive education programs. Barnard College has similarly been affiliated with Columbia University since its founding in 1888, but it continues to be independently governed.

Mount Holyoke College and Smith College are also members of Pioneer Valley's Five Colleges consortium. Bryn Mawr College is a part of the Tri-College Consortium in suburban Philadelphia, with its sister schools, Haverford College and Swarthmore College.

Formation and name

Barnard, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Radcliffe were given the name "the Seven Sisters" in 1927, because of their relative affiliations with the Ivy League men’s colleges.[1][5] The schools are sometimes referred to as "the Daisy Chain" or "the Heavenly Seven."

The name Seven Sisters is also a reference to the Greek myth of The Pleiades, the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas and the sea-nymph Pleione. The daughters (Maia, Electra, Taygete, Alcyone, Celaeno, Sterope, and Merope) were collectively referred to as The Seven Sisters. In the field of astronomy a star cluster, in the constellation of Taurus, is also referred to as The Pleiades or the Seven Sisters.

Coeducation

The seven colleges explored the issue of coeducation in a variety of ways.

Two, Radcliffe College and Vassar College, are no longer women's colleges. Radcliffe merged completely into Harvard College in 1999, and is now a research institute and no longer an undergraduate institution. The component parts of the College's campus, the Radcliffe Quadrangle and Radcliffe Yard, retain the designation "Radcliffe" in perpetuity, and serve or house both male and female students to this day. Vassar declined an offer to merge with Yale University and became independently coeducational in 1969.

Barnard College was founded in 1888 as a woman's college affiliated with Columbia University. However, it is independently governed, while making available to its students the instruction and the facilities of Columbia University. Columbia College, the university's largest liberal-arts undergraduate school, began admitting women in 1983 after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard for a merger along the lines of the one between Harvard College and Radcliffe and between Brown and Pembroke. Barnard has an independent faculty (subject to Columbia University tenure approval) and board of trustees. Columbia University issues its diplomas, however, and most of Barnard's classes and activities are open to all members of Columbia University, male or female, and vice versa, in a reciprocal arrangement dating from 1900.[6][7]

In 1969 Bryn Mawr and Haverford College (then all-male) developed a system of sharing residential colleges. When Haverford became coeducational in 1980, Bryn Mawr discussed the possibility of coeducation as well but decided against it.[8]

As with Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College, and Wellesley College decided against adopting coeducation. Mount Holyoke engaged in a lengthy debate under the presidency of David Truman over the issue of coeducation. On 6 November 1971, "after reviewing an exhaustive study on coeducation, the board of trustees decided unanimously that Mount Holyoke should remain a women's college, and a group of faculty was charged with recommending curricular changes that would support the decision."[9] Smith also made a similar decision in 1971.[10] Two years later, Wellesley also announced that it would not adopt coeducation.[11]

A June 3, 2008 article in The New York Times discussed the move by women's colleges in the United States to promote their schools in the Middle East. The article noted that in doing so, the schools promote the work of graduates of women's colleges such as Hillary Clinton, Emily Dickinson, Diane Sawyer, Katharine Hepburn and Madeleine K. Albright. The Dean of Admissions of Bryn Mawr College noted, "We still prepare a disproportionate number of women scientists [...] We’re really about the empowerment of women and enabling women to get a top-notch education." The article also contrasted the difference between women's colleges in the Middle East and "the American colleges [which] for all their white-glove history and academic prominence, are liberal strongholds where students fiercely debate political action, gender identity and issues like 'heteronormativity,' the marginalizing of standards that are other than heterosexual and cisgendered. Middle Eastern students who already attend these colleges tell of a transition that can be jarring." The article further quoted a Sri Lankan student (who had attended a coeducational school in Dubai) who stated that she was "shocked by the presence of so many lesbians among the students" and the "open displays of affection".[12]

Competitiveness

While Radcliffe no longer exists as an institution independent of Harvard College, the remaining seven sisters are considered highly competitive among liberal arts institutions in the United States. Wellesley College consistently ranks in the top 3 or 4 of national liberal arts colleges, and Smith and Vassar were most recently ranked 12 by U.S. News & World Report.[13] Applicants' GPA's tend to be over 3.6 combined with high SAT scores and strong extra-curricular leadership experience. Applicants tend to be academically driven and successful.

The Wall Street Journal recently summarized their college rankings of the seven sister colleges, including factors such as engagement, outcomes, resources and environment.[14]

Bryn Mawr College's Pembroke Hall

Bryn Mawr College's Pembroke Hall Mount Holyoke College (Mount Holyoke Female Seminary) in 1837

Mount Holyoke College (Mount Holyoke Female Seminary) in 1837

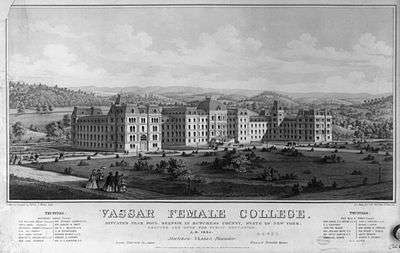

Vassar College in an engraving from 1862.

Vassar College in an engraving from 1862. Wellesley College Green Hall

Wellesley College Green Hall

Transgender issues

Since the late 2000s, there has been discussion and controversy over how to accommodate transgender inclusion at the remaining women's colleges. This has risen to attention due to a small, yet increasing number of students that have in the course of their times at the colleges transitioned from female to male (trans men),[15] and trans women applicants. Mount Holyoke became the first Seven Sisters college to accept transgender women in 2014.[16] Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Smith, and Wellesley College announced trans-inclusive admissions policies in 2015.[17][18][19]

In popular culture and the news

In the 2003 Simpsons episode "I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can", Lisa Simpson dreams that personifications of each of the Seven Sisters colleges are attempting to woo her into attending.[20]

The 1978 film National Lampoon's Animal House satirizes a common practice (until the mid-1970s), when women attending Seven Sister colleges were connected with or to students at Ivy League schools. The film, which takes place in 1962, shows fraternity brothers from Delta House of the fictional Faber College (based on Dartmouth College) taking a road trip to the fictional Emily Dickinson College (based on Mount Holyoke College) to obtain dates.[21]

In an early scene of the 1987 film “Dirty Dancing”, Dr. Jake Housemann (played by Jerry Orbach) in referring to his daughter, Baby Housemann (Jennifer Grey) announces that “Baby is going to Mount Holyoke in the fall.”

The movie and book Love Story shows a relationship between a Harvard man and Radcliffe woman.

In November, 2016, the presidents of the Seven Sister colleges collectively wrote an open letter to Steve Bannon, an appointee of the President-elect, who spoke negatively about the students.[22]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Irene Harwarth; Mindi Maline; Elizabeth DeBra. "Women's Colleges in the United States: History, Issues, and Challenges". U.S. Department of Education National Institute on Post-secondary Education, Libraries, and Lifelong Learning. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005.

- ↑ "About Mount Holyoke". mountholyoke.edu. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ↑ "Radcliffe Mission, Vision, and History". harvard.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ "Hard Earned Gains for Women at Harvard". The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ Robert A. McCaughey (Spring 2003). "Women and the Academy". Higher Learning in America, History BC4345x. Barnard College. Archived from the original on 2006-05-12.

- ↑ "Chronology". Barnard College. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Partnership with Columbia". Barnard College. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Bryn Mawr College". Bryn Mawr. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "A Detailed History". Mount Holyoke College. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Smith College Presidents". Smith College. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "WELLESLEY SAYS IT WON'T GO COED; Plans Drive for $70-Million Over Next 10 Years". The New York Times. March 9, 1973. p. 43. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Lewin, Tamar (June 3, 2008). "'Sisters' Colleges See a Bounty in the Middle East". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "US News Rankings".

- ↑ "Wall Street Journal Rankings".

- ↑ Brune, Adrian (April 8, 2007). "When She Graduates as He". The Boston Globe Magazine. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Kellaway, Mitch (2014-09-03). "WATCH: First of 'Seven Sisters' Schools to Admit Trans Women". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ "Barnard Announces Transgender Admissions Policy". Barnard College website. June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Gibson, Arlene (February 9, 2015). "A Letter from Bryn Mawr Board Chair Arlene Gibson". Bryn Mawr College website.

- ↑ "Admission Policy Announcement". Smith College website. May 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Seven Sisters". Mount Holyoke College.

- ↑ Landis, John (August 29, 2003). "Transcript". Live from the Headlines (Interview). Interviewed by Soledad O'Brien. CNN.

- ↑ DeCost-Klipa, Nik (November 21, 2016). "Seven Sisters colleges respond to Steve Bannon's derogatory remark with open letter". Boston Globe. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

References

- Creighton, Joanne V. "A Tradition of Their Own: Or, If a Woman Can Now Be President of Harvard, Why Do We Still Need Women’s Colleges?".

- Howard Greene; Mathew W. Greene (2000). Greenes' Guides to Educational Planning: The Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-095362-4.

- Dolkart, Andrew (1998). Morningside Heights: a history of its architecture & development. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07850-4.

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s (2nd edition). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

- Perkins, Linda M. (Spring 1998). "The Racial Integration of the Seven Sister Colleges". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (19): 104–08. doi:10.2307/2998936. JSTOR 2998936 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

External links

- "About the Seven Sisters"—Mount Holyoke College

- "College Women: Documenting the History of Women in Higher Education"—digital archives portal created by the libraries of the colleges formerly known as the "Seven Sisters" in 2015.