Sailfish

| Sailfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Istiophoriformes |

| Family: | Istiophoridae |

| Genus: | Istiophorus Lacépède, 1801 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

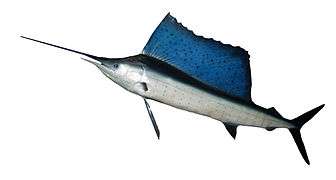

A sailfish is a fish of the genus Istiophorus of billfish living in colder areas of all the seas of the earth. They are predominantly blue to gray in colour and have a characteristic erectile dorsal fin known as a sail, which often stretches the entire length of the back. Another notable characteristic is the elongated bill, resembling that of the swordfish and other marlins. They are, therefore, described as billfish in sport-fishing circles.

Species

Two sailfish species have been recognized.[2][3] No differences have been found in mtDNA, morphometrics or meristics between the two supposed species and most authorities now only recognized a single species, (Istiophorus platypterus), found in warmer oceans around the world.[3][4][5][6] FishBase continues to recognize two species:[2]

- Atlantic sailfish (I. albicans).

- Indo-Pacific sailfish (I. platypterus).

Description

Sailfish grow quickly, reaching 1.2–1.5 m (3.9–4.9 ft) in length in a single year, and feed on the surface or at middle depths on smaller pelagic forage fish and squid. Sailfish were previously estimated to reach maximum swimming speeds of 35 m/s (130 km/h; 78 mph), but research published in 2015 and 2016 indicate sailfish do not exceed speeds between 10–15 m/s. During predator–prey interactions, sailfish reached burst speeds of 7 m/s (25 km/h; 16 mph) and did not surpass 10 m/s (36 km/h; 22 mph).[7][8] Generally, sailfish do not grow to more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in length and rarely weigh over 90 kg (200 lb). Sailfish have been reported to use their bills for hitting schooling fish by tapping (short-range movement) or slashing (horizontal large-range movement) at them.[9]

The sail is normally kept folded down when swimming and raised only when the sailfish attack their prey. The raised sail has been shown to reduce sideways oscillations of the head, which is likely to make the bill less detectable by prey fish.[7] This strategy allows sailfish to put their bills close to fish schools or even into them without being noticed by the prey before hitting them.[9][10]

Sailfish usually attack one at a time, and the small teeth on their bills inflict injuries on their prey fish in terms of scale and tissue removal. Typically, about two prey fish are injured during a sailfish attack, but only 24% of attacks result in capture. As a result, injured fish increase in number over time in a fish school under attack. Given that injured fish are easier to catch, sailfish benefit from the attacks of their conspecifics but only up to a particular group size.[11] A mathematical model showed that sailfish in groups of up to 70 individuals should gain benefits in this way. The underlying mechanism was termed protoco-operation because it does not require any spatial co-ordination of attacks and could be a precursor to more complex forms of group hunting.[11]

The bill movement of sailfish during attacks on fish is usually either to the left or to the right side. Identification of individual sailfish based on the shape of their dorsal fins identified individual preferences for hitting to the right or left side. The strength of this side preference was positively correlated with capture success.[12] These side-preferences are believed to be a form of behavioural specialization that improves performance. However, a possibility exists that sailfish with strong side preferences could become predictable to their prey because fish could learn after repeated interactions in which direction the predator will hit. Given that individuals with right- and left-sided preferences are about equally frequent in sailfish populations, living in groups possibly offers a way out of this predictability. The larger the sailfish group, the greater the possibility that individuals with right- and left-sided preferences are about equally frequent. Therefore, prey fish should find it hard to predict in which direction the next attack will take place. Taken together, these results suggest a potential novel benefit of group hunting which allows individual predators to specialize in their hunting strategy without becoming predictable to their prey.[12]

The injuries that sailfish inflict on their prey appear to reduce their swimming speeds, with injured fish being more frequently found in the back (compared with the front) of the school than uninjured ones. When a sardine school is approached by a sailfish, the sardines usually turn away and flee in the opposite direction. As a result, the sailfish usually attacks sardine schools from behind, putting at risk those fish that are the rear of the school because of their reduced swimming speeds.[13]

Timeline

References

- ↑ "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. 2002. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2013). Species of Istiophorus in FishBase. April 2013 version.

- 1 2 McGrouther, M. (2013). Sailfish, Istiophorus platypterus. Australian Museum. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Cardenas, G.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr., N.; Di Natale, A.; Die, D.; et al. (2011). "Istiophorus platypterus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2011: e.T170338A6754507. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170338A6754507.en. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ Gardieff, S: Sailfish. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Collette, B.B., McDowell, J.R. and Graves, J.E. (2006). Phylogeny of Recent billfishes (Xiphioidei). Bull. Mar. Sci. 79(3): 455-468.

- 1 2 Marras S, Noda T, Steffensen JF, Svendsen MBS, Krause J, Wilson ADM, Kurvers RHJM, Herbert-Read J & Domenic P 2015) "Not so fast: swimming behavior of sailfish during predator–prey interactions using high-speed video and accelerometry". Integrative and Comparative Biology 55: 718-727.

- ↑ Svendsen MBS, Domenici P, Marras S, Krause J, Boswell KM, Rodriguez-Pinto I, Wilson ADM, Kurvers RHJM, Viblanc PE, Finger JS & Steffensen JF (2016) "Maximum swimming speeds of sailfish and other large marine predatory fish species based on muscle contraction time: A myth revisited". Biology Open, 5: 1415-1419.

- 1 2 Domenici P, Wilson ADM, Kurvers RHJM, Marras S, Herbert-Read JE, Steffensen JF, Krause S, Viblanc PE, Couillaud P & Krause J (2014) "How sailfish use their bill to capture schooling prey". Proceedings of the Royal Society London B, 281: 20140444.

- ↑ Sailfish Hunting Sardines – Youtube.

- 1 2 Herbert-Read JE, Romanczuk P, Krause S, Strömbom D, Couillaud P, Domenici P, Kurvers RHJM, Marras S, Steffensen JF, Wilson ADM & Krause J (2016) "Group hunting sailfish alternate their attacks on their grouping prey to facilitate hunting success". Proceedings of the Royal Society London B, 283: 20161671.

- 1 2 Kurvers RHJM, Krause S, Viblanc PE, Herbert-Read JE, Zalansky P, Domenici P, Marras S, Steffensen JF, Wilson ADM, Couillaud P & Krause J (2017) "The evolution of lateralisation in group hunting sailfish". Current Biology.

- ↑ Krause J and Ruxton GD (2002) Living in Groups Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198508182

- Schultz, Ken (2003) Ken Schultz's Field Guide to Saltwater Fish pp. 162–163, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471449959.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Istiophorus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Istiophorus |