SS Central America

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Central America |

| Operator: | United States Mail Steamship Company |

| Fate: | Sank September 12, 1857 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 2,141 long tons (2,175 t) |

| Length: | 278 ft (85 m) |

| Beam: | 40 ft (12 m) |

| Crew: |

Captain William Lewis Herndon First Officer Charles W. van Rensselaer |

SS Central America, known as the Ship of Gold, was a 280-foot (85 m) sidewheel steamer that operated between Central America and the eastern coast of the United States during the 1850s. She was originally named the SS George Law, after Mr. George Law of New York. The ship sank in a hurricane in September 1857, along with more than 420 passengers and crew and 30,000 pounds (14,000 kg) of gold, contributing to the Panic of 1857.

Sinking

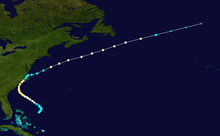

On 3 September 1857, 477 passengers and 101 crew left the Panamanian port of Colón, sailing for New York City under the command of William Lewis Herndon. The ship was heavily laden with 10 short tons (9.1 t) of gold prospected during the California Gold Rush. After a stop in Havana, the ship continued north.

On 9 September 1857, the ship was caught up in a Category 2 hurricane while off the coast of the Carolinas. By 11 September, the 105 mph (170 km/h) winds and heavy seas had shredded her sails, she was taking on water, and her boiler was threatening to fail. A leak in one of the seals between the paddle wheel shafts and the ship's sides sealed its fate. At noon that day, her boiler could no longer maintain fire. Steam pressure dropped, shutting down both the bilge pumps. Also, the paddle wheels that kept her pointed into the wind failed as the ship settled by the stern. The passengers and crew flew the ship's flag inverted (a distress sign in the US) to signal a passing ship. No one came.

A bucket brigade was formed, and her passengers and crew spent the night fighting a losing battle against the rising water. During the calm of the hurricane, attempts were made to get the boiler running again, but these failed. The second half of the storm then struck. The ship was now on the verge of foundering. Without power, the ship was carried along with the storm and the strong winds would not abate. The next morning, September 12, two ships were spotted, including the brig Marine. Among her passengers, 153 passengers, primarily women and children, made their way over in lifeboats. The ship remained in an area of intense winds and heavy seas that pulled the ship and most of her company away from rescue. Central America sank at 8:00 that evening. As a consequence of the sinking, 425 people were killed. A Norwegian bark, Ellen, rescued an additional 50 from the waters.[1] Another three were picked up over a week later in a lifeboat.

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, greatest attention was paid to the loss of life, which was described as "appalling" and as having "no parallel" among American navigation disasters.[2] At the time of her sinking, Central America carried gold then valued at approximately US$8,000,000 (modern monetarily equivalent to $292 million, assuming a gold value of $1,000 per troy ounce). The loss shook public confidence in the economy, and contributed to the Panic of 1857. The valuation of the ship itself was substantially less than those lost in other disasters of the period, being $140,000 (equivalent to $3,680,000 in 2017).[2]

Commander William Lewis Herndon, a distinguished officer who had served during the Mexican–American War and explored the Amazon Valley, was captain of Central America, and went down with his ship. Two US Navy ships were later named USS Herndon in his honor, as was the town of Herndon, Virginia. Two years after the sinking, his daughter Ellen married Chester Alan Arthur, later the 21st President of the United States.

Search and discovery

The ship was located by the Columbus-America Discovery Group of Ohio, led by Tommy Gregory Thompson, using Bayesian search theory. A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) was sent down on 11 September 1988.[3] Significant amounts of gold and artifacts were recovered and brought to the surface by another ROV built specifically for the recovery. The total value of the recovered gold was estimated at $100–150 million. A recovered gold ingot weighing 80 lb (36 kg) sold for a record $8 million and was recognized as the most valuable piece of currency in the world at that time.[4]

Thirty-nine insurance companies filed suit, claiming that because they paid damages in the 19th century for the lost gold, they had the right to it. The team that found it argued that the gold had been abandoned. After a legal battle, 92% of the gold was awarded to the discovery team in 1996.[5]

Thompson was sued in 2005 by several of the investors who had provided $12.5 million in financing, and in 2006 by several members of his crew, over a lack of returns for their respective investments. Thompson went into hiding in 2012.[5][6][7][8] A receiver was appointed to take over Thompson's companies and, if possible, salvage more gold from the wreck,[6] in order to recover money for Thompson's various creditors.[5]

In March 2014, a contract was awarded to Odyssey Marine Exploration to conduct archeological recovery and conservation of the remaining shipwreck.[9] The original expedition had only excavated "5 percent" of the ship.[5]

Thompson was located in January 2015, along with assistant Alison Antekeier, by US Marshals agents, and was extradited to Ohio to provide an accounting of the expedition profits.[7][8]

See also

Other successful treasure recoveries include:

References

- ↑ http://www.columbia.edu/~dj114/SS_Central_America.pdf

- 1 2 Staff (6 November 1857). "Steamship Disasters". Olney Times (reprint from "Journal of Commerce"). Retrieved 2015-07-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Kinder, Gary. "Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea". New York: Atlantic Monthly, 1998. Print.

- ↑ Anastasia Hendrix, Chronicle Staff Writer (9 November 2001). "Gold Rush brick sells for $8 million / 80-pound ingot bought by executive". SFGate. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee Myers, Amanda (13 September 2014). "Feds chase treasure hunter turned fugitive". USA Today. AP. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- 1 2 Gray, Kathy (29 May 2014). "Judge appoints receiver in gold-ship lawsuit". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- 1 2 "US fugitive treasure hunter appears in Florida court". BBC. BBC News. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- 1 2 Phillip, Abby. "How treasure hunter Tommy Thompson, 'one of the smartest fugitives ever,' was caught". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ "Odyssey Marine Exploration to salvage gold from 1857 shipwreck". Tampa Bay Times. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014.

Further reading

- Kinder, Gary. (1998). Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-717-8

- Thompson, Tommy. (2000). America's Lost Treasure. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-732-1

- Klare, Norman. (1991 and 2005). The Final Voyage of the Central America, 1857: The Saga of a Gold Rush Steamship. ISBN 0-87062-210-2 and ISBN 0-9764403-0-X

- Stone, Lawrence D. Search for the SS Central America: Mathematical Treasure Hunting. Technical Report, Metron Inc. Reston, Virginia.

External links

- Final Voyage of the Central America by Normand E. Klare 1982 Second Edition

- America's Lost Treasure: The Wreck of the SS Central America

- The Central America Engulphed (sic) in the Ocean

- Wreck of the Central America

- "The Central America: Further of the Disaster", New York Times, 23 Sept 1857

- – "Detailed and Very Interesting Statement of Captain Badger" and "Protest of the Surviving Officers"

- NOAA list of deadliest hurricanes

- http://www.wncrocks.com/ARCTIC%20DISCOVERER.html

Coordinates: 31°35′N 77°02′W / 31.583°N 77.033°W