SPG20

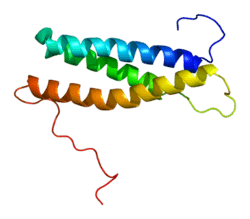

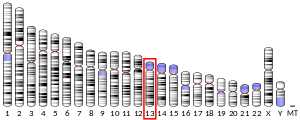

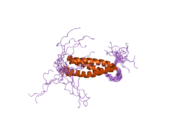

Spartin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SPG20 gene.[3][4][5]

This gene encodes a protein that contains a MIT (Microtubule Interacting and Trafficking molecule) domain. This protein may be involved in endosomal trafficking, microtubule dynamics, or both functions. Frameshift mutations associated with this gene cause autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia 20 (Troyer syndrome).[5] Troyer syndrome (SPG20) is a complicated type of hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs).[6] HSP is a category of neurological disorder characterized by spasticity and muscle weakness in the lower limbs.[6]

Background

The original description of this gene mutation and associated symptoms were described in 1967.[7] This mutation is commonly found in high frequency with the Amish population.[4] Newer studies have found that the mutation is not isolated to the Amish population, but also resides in the Omani population.[7]

Presentation

This syndrome is not only characterized by spasticity and weakness in the lower limbs, but also with dysarthria, mental retardation or mild developmental delay, and muscle wasting or muscle atrophy.[6]

Physical

Individuals appear to have difficulty walking, and report a clumsy, spastic gait which worsens over time.[7] Some additional common physical features include overgrowth of the jaw bone, hammer toes, hand and feet abnormalities, and pes cavus.[7]

Cognitive

Cognitive challenges, including developmental delay and difficulty with performance in school, may affect individuals with this syndrome.[7]

Neurologic

Neurologic examination of individuals with this mutation may show dysmetria in the upper extremities, hyperreflexia, distal amyotrophy and ankle clonus, in addition to spasticity, weakness and dysarthria.[7]

Diagnostic Imaging

The cerebellar vermis may present with mild atrophy and a loss of white matter volume.[7]

Through Lifespan

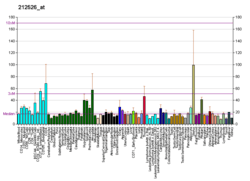

Facial dysmorphism and subtle skeletal features are common in younger children.[7] The condition progressively worsens, as spasticity and distal amyotrophy symptoms are revealed more in teenage years.[7] SPG20 expression in the adult is relatively modest, however it is widespread in the nervous system.[7] Longitudinal comparison of magnetic resonance imaging concluded that there was a progression of the syndrome; thus, the condition appears to worsen over time.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000133104 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Cross HE, McKusick VA (Jun 1967). "The Troyer syndrome. A recessive form of spastic paraplegia with distal muscle wasting". Arch Neurol. 16 (5): 473–85. doi:10.1001/archneur.1967.00470230025003. PMID 6022528.

- 1 2 Patel H, Cross H, Proukakis C, Hershberger R, Bork P, Ciccarelli FD, Patton MA, McKusick VA, Crosby AH (Jul 2002). "SPG20 is mutated in Troyer syndrome, an hereditary spastic paraplegia". Nat Genet. 31 (4): 347–8. doi:10.1038/ng937. PMID 12134148.

- 1 2 "Entrez Gene: SPG20 spastic paraplegia 20, spartin (Troyer syndrome)".

- 1 2 3 Bakowska, J.C.; Jenkins, R.; Pendleton, J.; Blackstone, C. (2005). "The Troyer syndrome (SPG20) protein interacts with Eps15". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 334 (4): 1042–1048. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.201. PMID 16036216.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Manzini, M. C.; Rajab, A.; Maynard, T. M.; Mochida, G. H.; Tan, W.; Nasir, R.; et al. (2010). "Developmental and degenerative features in a complicated spastic paraplegic". Annals of Neurology. 67: 516–525. doi:10.1002/ana.21923. PMC 3027847.

External links

Further reading

- Hillier LD, Lennon G, Becker M, et al. (1997). "Generation and analysis of 280,000 human expressed sequence tags". Genome Res. 6 (9): 807–28. doi:10.1101/gr.6.9.807. PMID 8889549.

- Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Miyajima N, et al. (1998). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. IX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which can code for large proteins in vitro". DNA Res. 5 (1): 31–9. doi:10.1093/dnares/5.1.31. PMID 9628581.

- Auer-Grumbach M, Fazekas F, Radner H, et al. (1999). "Troyer syndrome: a combination of central brain abnormality and motor neuron disease?". J. Neurol. 246 (7): 556–61. doi:10.1007/s004150050403. PMID 10463356.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Ciccarelli FD, Proukakis C, Patel H, et al. (2003). "The identification of a conserved domain in both spartin and spastin, mutated in hereditary spastic paraplegia". Genomics. 81 (4): 437–41. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00011-9. PMID 12676568.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, et al. (2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs". Nat. Genet. 36 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Dunham A, Matthews LH, Burton J, et al. (2004). "The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 13". Nature. 428 (6982): 522–8. doi:10.1038/nature02379. PMC 2665288. PMID 15057823.

- Liu M, Liu Y, Cheng J, et al. (2004). "Transactivating effect of hepatitis C virus core protein: a suppression subtractive hybridization study". World J. Gastroenterol. 10 (12): 1746–9. PMID 15188498.

- Colland F, Jacq X, Trouplin V, et al. (2004). "Functional proteomics mapping of a human signaling pathway". Genome Res. 14 (7): 1324–32. doi:10.1101/gr.2334104. PMC 442148. PMID 15231748.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Bakowska JC, Jenkins R, Pendleton J, Blackstone C (2005). "The Troyer syndrome (SPG20) protein spartin interacts with Eps15". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334 (4): 1042–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.201. PMID 16036216.

- Lu J, Rashid F, Byrne PC (2006). "The hereditary spastic paraplegia protein spartin localises to mitochondria". J. Neurochem. 98 (6): 1908–19. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04008.x. PMID 16945107.

- Bakowska JC, Jupille H, Fatheddin P, et al. (2007). "Troyer syndrome protein spartin is mono-ubiquitinated and functions in EGF receptor trafficking". Mol. Biol. Cell. 18 (5): 1683–92. doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0833. PMC 1855030. PMID 17332501.

- Bakowska, J.C.; Jenkins, R.; Pendleton, J.; Blackstone, C. (2005). "The Troyer syndrome (SPG20) protein interacts with Eps15". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 334 (4): 1042–1048. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.201. PMID 16036216.

- Manzini, M. C.; Rajab, A.; Maynard, T. M.; Mochida, G. H.; Tan, W.; Nasir, R.; et al. (2010). "Developmental and degenerative features in a complicated spastic paraplegic". Annals of Neurology. 67: 516–525. doi:10.1002/ana.21923. PMC 3027847.

- Ciccarelli, F. D.; Patton, M. A.; McKusick, V. A.; Crosby, A. H. (2002). "SPG20 is mutated in Troyer syndrome, an hereditary spastic paraplegia". Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 347–348. doi:10.1038/ng937. PMID 12134148.