Risk-limiting audit

A risk limiting post-election audit is one of several types of election audits. It is based on hand counts of statistical samples of paper ballots, which are stored from election day to the time of the audit. It tests whether election results identified the correct winner(s).[1] Specifically, if samples find few discrepancies, the public knows there is a limited risk that the initial winners are wrong. If samples find substantial discrepancies, the risk-limiting audit, like most but not all other election audits, requires a 100% recount by hand, to identify the correct winner(s).

Categories of audits

There are two types of election audits: process audits, which determine whether appropriate procedures were followed, and results audits, which determine whether votes were counted accurately.[2] Risk-limiting audits are one form of a results audit.

There are three types of risk-limiting audits:[3]

- Ballot comparison. Know how computers counted each ballot ("cast vote record"), compare the computer and manual interpretations of a random sample of ballots, count and report differences in these interpretations

- Ballot polling. Know computer total for the election, count a random sample of ballots, report differences between computer and manual percentages

- Batch comparison. Know computer total for each batch of ballots (e.g. precinct), hand-count all ballots in a random sample of batches, report any differences between computer and manual totals for each batch

Colorado uses the first system in most counties, and the second in a few counties which lack "cast vote records."[4]

Implementation

The process starts with election officials selecting a ‘risk limit,’ such as 9% in Colorado,[5] meaning that if there are any erroneous winners in the initial results, the audit will catch at least 91% of them and let up to 9% stay undetected and take office.[3][6] Using formulae,[3] [7] [8] [9] officials identify a sample size for each race they intend to verify. The size of the sample depends primarily on the margin of victory in the targeted race. They then generate a series of random numbers identifying specific ballots to pull from storage, such as the 23rd, 189th, 338th, 480th ballots in precinct 1, and other random numbers in other precincts. Paper ballots in the sample are then manually compared to the computer results. If the audit sample produces the same result as the computer results, the outcome is confirmed, subject to the risk limit, and the audit is complete. If the audit sample shows enough discrepancies to call the outcome into question, a larger sample is selected and counted. This process can continue until the sample confirms the original winner or a different winner is determined by hand-counting all ballots.[10]

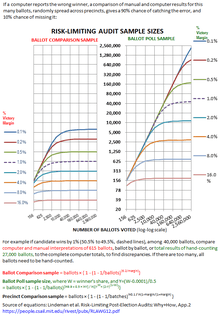

The three approaches are listed in order of increasing numbers of ballots which need to be hand-counted. For example in a jurisdiction with 64,000 ballots, an 8% margin of victory, and allowing 10% of any mistakes to go undetected, ballot comparison, on average, needs 80 ballots, ballot polling needs 700 ballots, and batch comparison needs 13,000 ballots (in 26 batches).[3]

Sample sizes rise rapidly for narrower margins, with all methods. Even in a smaller jurisdiction, with 4,000 ballots, ballot comparison would need 300 ballots for a race with a 2% margin of victory and 3,000 ballots for a 0.1% margin of victory. Ballot polling or batch comparison would need a full hand count. Margins under 0.1% occur in one in sixty to one in 460 races. Large numbers of races on a ballot raise the chances that these small margins and large samples will occur in a jurisdiction.

If the samples do not confirm the initial results, more rounds of sampling may be done, but if it appears the initial results are wrong, risk-limiting audits require a 100% hand count to change the result.[3]

Jurisdictions using method 1, compare paper ballots to the computer's cast vote records. A bug or smart hacker could generate cast vote records which match the physical ballots, but the computers can still print out totals which create a different outcome from the true sum of the honest ballot-by-ballot records. So the system needs an independent check that the computer totals match the ballot-by-ballot records.[6] [11] Colorado says it has such a system, but it is not yet publicly documented.[12] Method 1 also requires the ballots to be kept in strict order so one can compare the computer interpretations of sampled ballots with those exact physical ballots.[13]

All the methods, when done for a state-wide election, involve manual work throughout the state, wherever ballots are stored, so the public and candidates need observers at every location to be sure procedures are followed. However in Colorado and most states the law does not require any of the audit work to be done in public.[14]

Costs of actual hand counts in 2004 ranged from $0.36 per ballot to count one race in Washington State, including overhead (training, supervision, space rental), to $3.39 per ballot to count 21 contests on each ballot in Nevada, excluding overhead, or $0.18 per contest per ballot.[15] These involved hand-counting all ballots in a precinct, so they are relevant to 100% hand-counts, when needed. Sample counts have fewer ballots, but extra costs for pulling out the sampled ballots and putting them back, and similar overheads for training and supervision.

Keeping paper ballots secure

Auditing is done several days after the election, so paper ballots and computer files need to be kept securely. Physical security has its own large challenges. No US state has adequate laws on physical security of the ballots.[16] Security recommendations for elections include: starting audits as soon as possible after the election, preventing access by anyone alone,[17] which would typically require two locks, and no one having keys to both locks, having risks identified by people other than those who design or manage the system, using background checks and tamper-evident seals,[18] [3] although seals can typically be removed and reapplied without damage, especially in the first 48 hours, and detecting subtle tampering requires substantial training.[19] [20] [21]

Experienced testers can usually bypass all physical security systems. Security equipment is vulnerable before and after delivery. Insider threats and the difficulty of following all security procedures are usually under-appreciated, and most organizations do not want to learn their vulnerabilities.[22]

State variations

As of early 2017, about half the states require some form of results audit.[14] Typically, these states prescribe audits that check only a small flat percentage, such as 1%, of voting machines. As a result, few jurisdictions conduct audits that are rigorous or timely enough to detect and correct counting errors before election results are declared final.[23][24]

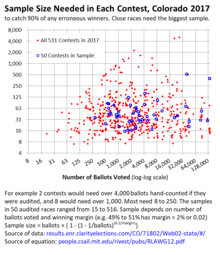

In 2017, Colorado[25] became the first state to implement rigorous risk-limiting audits, auditing one race in each of 50 of its 64 counties.[26] Rhode Island passed legislation requiring that state's Board of Elections to implement risk-limiting audits beginning in 2018. Individual jurisdictions elsewhere may be using the method on the local election clerks' initiative.

Endorsements

In 2010, the American Statistical Association endorsed methods 1 and 3, ballot comparisons and batch comparisons, as long as there is public verifiability:

- "A batch is a group of ballots (or even one ballot) for which machine and hand counts can be compared."

- "Ensuring verifiability... publishing machine counts for all batches prior to their being sampled demonstrates that the numbers that the audit checks are the same as the subtotals included in the machine-count outcome."[11]

In 2008 the Brennan Center for Justice and several election integrity groups endorsed methods 2 and 3, ballot polling and batch comparisons, similarly insisting on public verifiability:

- "For each selected audit unit, the audit must compare vote count subtotals from the preliminary reported election results for the contest, with hand-to-eye counts of the corresponding paper records... subtotals for each batch must be reported prior to the audit as part of the election results."

- "The public is given sufficient access to witness and verify the random selection of the audit as well as the manual count."[17]

In 2014, the Presidential Commission on Election Administration recommended the methods in broad terms:

- "Commission endorses both risk-limiting audits that ensure the correct winner has been determined according to a sample of votes cast, and performance audits that evaluate whether the voting technology performs as promised and expected."[27]

By selecting samples of varying sizes dictated by statistical risk, risk-limiting audits eliminate the need to count all the ballots to obtain a rapid test of the outcome (that, is, who won?), while providing some level of statistical confidence.

In 2011, the federal Election Assistance Commission initiated grants for pilot projects to test and demonstrate the method in actual elections.[28]

Professor Phillip Stark of the University of California at Berkeley has posted tools for the conduct of risk-limiting audits on the university's website.[29]

See also

References

- ↑ Cyrus Farivar (2012-07-25). "Saving throw: securing democracy with stats, spreadsheets, and 10-sided dice". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- ↑ "Report on Election Auditing by the Election Audits Task Force of the League of Women Voters of the United States" (PDF). League of Women Voters. 2009. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lindeman, Mark (executive editor), Jennie Bretschneider, Sean Flaherty, Susannah Goodman, Mark Halvorson, Roger Johnston, Ronald L. Rivest, Pam Smith, Philip B. Stark (2012-10-01). "Risk-Limiting Post-Election Audits: Why and How" (PDF). University of California at Berkeley. pp. 3, 16. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ Volkosh, Dan (2018-01-04). "Voting Systems Public". Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Round #1 State Report". www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/auditCenter.html. 2017-11-20. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- 1 2 Stark, Philip (2012-03-16). "Gentle Introduction to Risk-limiting Audits" (PDF). IEEE Security and Privacy – via University of California at Berkeley, pages 1, 3.

- ↑ Stark, Philip (2010-08-01). "Super-Simple Simultaneous Single-Ballot Risk-Limiting Audits" (PDF). Proceedings of the USENIX Electronic Voting Technology Workshop/Workshop on Trustworthy Elections (EVT/WOTE), Aug. 2010.

- ↑ Lindeman, Mark, Philip B. Stark, Vincent S. Yates (2012-08-06). "BRAVO: Ballot-polling Risk-limiting Audits to Verify Outcomes" (PDF). EVT/WOTE.

- ↑ Wald, A. (1945-06-01). "Sequential Tests of Statistical Hypotheses". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 16 (2): 117–186. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177731118. ISSN 0003-4851.

- ↑ http://electionaudits.org/bp-risklimiting

- 1 2 Statement on Risk-limiting Auditing, American Statistical Association, April 2010. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ Lindeman, Mark, Ronald L. Rivest, Philip B. Stark and Neal McBurnett (2018-01-03). "Comments re statistics of auditing the 2018 Colorado elections" (PDF). Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ Lovato, Jerome, Danny Casias, and Jessi Romero. "Colorado Risk-Limiting Audit:Conception to Application" (PDF). Bowen center for Public Affairs and Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 "State Audit Laws". Verified Voting. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ Theisen, Ellen (2004). [www.votersunite.org/info/CostEstimateforHandCounting.pdf "Cost Estimate for Hand Counting 2% of the Precincts in the U.S."] Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). votersunite.org. Retrieved 2018-05-04. - ↑ Benaloh, Public Evidence from Secret Ballots; et al. (2017). Electronic voting : second International Joint Conference, E-Vote-ID 2017, Bregenz, Austria, October 24-27, 2017, proceedings (PDF). Cham, Switzerland. p. 122. ISBN 9783319686875. OCLC 1006721597.

- 1 2 Lindeman, Mark, Mark Halvorson, Pamela Smith, Lynn Garland, Vittorio Addona, Dan McCrea (2008-09-01). "Best Practices: Chain of Custody and Ballot Accounting, ElectionAudits.org" (PDF). Brennan Center for Justice et al. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Chapter 3. PHYSICAL SECURITY" (PDF). US Election Assistance Commission. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Johnston, Roger G., and Jon S. Warner (2012-07-31). "How to Choose and Use Seals". Army Sustainment. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ↑ Coherent Cyber, Freeman, Craft McGregor Group (2017-08-28). "Security Test Report ES&S Electionware 5.2.1.0" (PDF): 9 – via California Secretary of State.

- ↑ Stauffer, Jacob (2016-11-04). "Vulnerability & Security Assessment Report Election Systems &Software's Unity 3.4.1.0" (PDF) – via Freeman, Craft, MacGregor Group for California Secretary of State.

- ↑ Seivold, Garett (2018-04-02). "Physical Security Threats and Vulnerabilities - LPM". losspreventionmedia.com. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Counting Votes 2012: A State by State Look at Voting Technology Preparedness, Pamela Smith, Verified Voting Foundation; Michelle Mulder, Rutgers School of Law-Newark; Susannah Goodman, Common Cause Education Fund, 2012. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ Confidence in the Electoral System: Why We Do Auditing, Michael W. Trautgott and Frederick G. Conrad, in Confirming Elections: Creating Confidence and Integrity Through Election Auditing, R. Michael Alvarex, Lonna Rae Atkeson, and Thad E. Hall, eds., Palgrave MacMillan, 2012.

- ↑ Paul, Jesse (2017-11-22). "Colorado's first-of-its-kind election audit is complete, with all participating counties passing". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

- ↑ Casias, Danny (2017-11-08). "Audited contests in each county for 2017 RLA (XLSX)". www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/auditCenter.html. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ↑ The American Voting Experience: Report and Recommendations of the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, January 2014

- ↑ Post-Election Risk-Limiting Audit Pilot Program 2011-2013, Final Report to the United States Election Assistance Commission, California Secretary of State 2013. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ "Tools for Comparison Risk-Limiting Election Audits". www.stat.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-17.