Election audits

Election auditing refers to any review conducted after polls close for the purpose of determining whether the votes were counted accurately (a results audit) or whether proper procedures were followed (a process audit), or both.

Both results and process audits can be performed between elections for purposes of quality management, but if results audits are to be used to protect the official election results from undetected fraud and error, they must be completed before election results are declared final. [1]

Recounts may be considered to be a specific type of audit, but not all audits are recounts. The Verified Voting Foundation explains the difference between audits and recounts: Post-election audits are performed to “routinely check voting system performance…not to challenge to the results, regardless of how close margins of victory appear to be", while "recounts repeat ballot counting (and are performed only) in special circumstances, such as when preliminary results show a close margin of victory. Post-election audits that detect errors can lead to a full recount.”[2] In the US, recount laws vary by state, but typically require recounting 100% of the votes, while audits may use samples. Recounts incorporate elements of both results and process audits.

The need for verification of election results

In jurisdictions that tabulate election results exclusively with manual counts from paper ballots, or 'hand counts', officials rarely rely on a single person to view and count the votes. Instead, valid hand-counting methods incorporate redundancy, so that more than one person views and interprets each vote and more than one person confirms the accuracy of each tabulation. In this way, the manual count incorporates a confirmation step, and a separate audit may not be considered necessary.

However, when votes are read and tabulated electronically, confirmation of the results' accuracy must become a separate process.

Within and outside elections, use of computers for decision support comes with certain IT risks. Election-Day electronic miscounts can be caused by unintentional human error, such as incorrectly setting up the computers to read the unique ballot in each election and undetected malfunction, such as overheating or loss of calibration. Malicious intervention can be accomplished by either corrupt insiders or external hackers who accessed the software before Election Day.[3][4]

Computer-related risks specific to elections include local officials’ inability to draw upon the level of IT expertise available to managers of commercial decision-support computer systems[5] and the intermittent nature of elections, which requires reliance on a large temporary workforce to manage and operate the computers.[6]

To reduce the risk of flawed Election-Day output, election managers like other computer-dependent managers rely on testing and ongoing IT security. In the field of elections management, these measures take the form of federal certification of the electronic elections system designs;[7] security measures in the local election officials’ workplaces; and pre-election testing.[8]

A third risk-reduction measure is performed after the computer has produced its output: Routinely checking the computers' output for accuracy, or auditing. Outside elections,auditing practices in the private sector and in other government applications are routine and well developed. In the practice of elections administration, however, the Pew Charitable Trusts stated in 2016, “Although postelection audits are recognized as a best practice to ensure that voting equipment is functioning properly, that proper procedures are being followed, and that the overall election system is reliable, the practice of auditing is still in its relative infancy. Therefore, a consensus has not arisen about what constitutes the necessary elements of an auditing program.”[9]

Routine results audits also support voter confidence by improving election officials' ability to respond effectively to allegations of fraud or error.[10]

Audit challenges unique to election results

Confirming that votes were credited to the correct candidates’ totals might seem to be a relatively uncomplicated task, but election managers face several audit challenges not present for managers of other decision-support IT applications. Primarily, ballot privacy prevents election officials from associating individual voters with individual ballots. This makes it impossible for election officials to use some standard audit practices such as those banks use to confirm that ATMs credited deposits to the correct account.

Another challenge is the need for a prompt and irrevocable decision. Election results need to be confirmed promptly, before officials are sworn into office. In many commercial uses of information technology, managers can reverse computer errors even when detected long after the event. However, once elected officials are sworn into office, they begin to make decisions such as voting on legislation or signing contracts on behalf of the government. Even if the official were to be removed because a computer error was discovered to have put that official in office, it would not be possible to reverse all the consequences of the error.

The intermittent nature of elections is another challenge. In most jurisdictions, elections take place no more than four times a year. This prevents development of a full-time, practiced workforce, for either the elections[11] or the audits. Turning election audits over to an independent, disinterested professional accounting firm is another option not available to election officials. Because election results affect everyone, including the election officials themselves, truly disinterested auditors do not exist. Therefore, audit transparency is required to provide credibility.

Attributes of a good election results audit

No governing body or professional association has yet adopted a definitive set of best practices for election audits. However, in 2007 a group of election-integrity organizations, including the Verified Voting Foundation, Common Cause, and the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law collaborated with the American Statistical Association to produce a set of recommended best practices for post-election results audits:

- Transparency: The public must be allowed to observe, verify, and point out procedural mistakes in all phases of the audit. This requires that audit procedures and standards be adopted, in written form, and made available before the election.

- Independence: While the actual work of post-election audits may be best performed by the officials who conduct the elections, the authority and regulation of post-election audits should be independent of officials who conduct the elections.

- Paper Records: Vote-counting in the audit should be performed with hand-to-eye counts of voter-marked, voter-verified paper ballots.

- Ballot Accounting (chain of custody, or internal control): The records used in the audit must be verified to be true and complete records of the election.

- Confirmation of the correct winners: The audits must reach statistical confidence that the computer-tabulated results identified the correct winners.

- Addressing Discrepancies: When discrepancies are found, investigation is conducted to determine cause of the discrepancies.

- Comprehensive: The ballot-sample selection process includes all jurisdictions and all ballot types (e.g., absentee, mail-in and accepted provisional ballots).

- Additional Targeted Samples: The audit includes a limited non-random sample selected on the basis of factors useful for building voter confidence or improving election management, such as Election-Day problems or preliminary results that deviate significantly from historical voting patterns.

- Binding on Official Results: Post-election audits must be completed before election results are declared official and final, and must either verify or correct the outcome.

Current practices in election results auditing in the United States

Computerization of elections occurred rapidly in the United States following the presidential election of 2000, in which imprecise vote-counting practices played a controversial role, and the subsequent adoption of the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002. The rapid switch to computerized vote tabulation forced election officials to abandon many pre-automation practices that had been used to verify vote totals, such as the redundancy included in valid hand-counting procedures.[12]

According to information from state profiles provided by Verified Voting, as of early 2018, only Arizona, Colorado[13], Minnesota, New Mexico, the District of Columbia, and (in legislation that will not be fully implemented until 2020) Rhode Island require local election officials to perform audits that:

- are completed promptly, before official results can be certified;

- expand the audit to a full recount whenever the audit detects serious discrepancies in the original sample; and

- are binding on the official results.

If followed by local election officials, such requirements create an opportunity to detect and correct any outcome-altering miscounts (whether caused by accident or fraud) that affected the preliminary Election-Night counts.

An additional 19 states prescribe audits that check a flat percentage, typically between 1 and 3 percent, of voting machines or precincts. These audits can detect problems in the individual voting machines selected for audit, but cannot confirm the correct results except in races with very large margins between the winner and losers.[14]

Finally, 26 states finalize official election results without verifying computer-tabulated vote totals. These states either have no audit requirements, or in four states (Florida, Vermont, Virginia, and Wisconsin) allow audits to be delayed until after winners are certified.

Other ways to group the states include that 20 states audit by means of hand counts; others use machines or a mix. Ten states audit all races on the ballot; others generally audit the top race and 1-4 others. In 14 states the audit results are used to revise official winners when there is a discrepancy. Another 10 may revise official results, depending on local judgment, and in 9 states the audit creates a report without changing official results, including large states like California, Florida and Illinois. Only two states use hand counts to audit all races, and use the results to revise winners; both are small, Alaska and West Virginia.[15]

Election audit practices, by state

| State | Method of Auditing Ballots | Do Audits Revise Election Outcomes? | Number of Races Audited | Level of Discrepancy to Trigger Action | Action if Discrepancy | State Gets Report? | Which Units Are Sampled? | Sample Size | Can Public See Ballot Marks? | What's Done if Some Ballots Are Missing? | Law | Rules | 2017 Population, Millions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | Hand count of precinct ballots[18] | No | All | No rules | Report[19] | Yes | precincts or machines | 1% | No | Cal. Elec. Code §336.5, §15360 (West 2015) | 40 | ||

| Texas | None on paperless machines, which most counties use, hand count otherwise | Maybe | 6-Sec. of State chooses 3 races + 3 ballot items | Any | Determine cause | Yes | precincts | at least 1% or 3, not paperless machines | No | Tex. Election Code Ann. §127.201 (Vernon 2015) | Election Advisory No. 2012-03 | 28 | |

| Florida | Count with machines, independent of election, or by hand | No | all by machine, or 1 by hand, randomly chosen by each county | No rules | Report | Yes | precincts | 20%-100% by machine or 2% by hand | No | Fla. Stat. Ann. §101.591 | 21 | ||

| New York | Count with machines different from voting system or by hand | Yes | All | Any | Expand sample in stages to full recount. Unclear if just the affected office | Yes | machines | 3% | No | N.Y. Election Law § 9-211 (McKinney 2015) | 9 N.Y. Comp. Rules & Regs. 6210.18 | 20 | |

| Pennsylvania | Count with machines different from voting system or by hand: the ballot images created by the election machines | Maybe | All | No rules | No rules | No | ballot images from paperless machines | lesser of 2% or 2,000 ballot images | No | Pa. Cons. Stat. tit. 25 §3031.17 | 13 | ||

| Illinois | Count with machines the optical ballots, which are common, others by hand or different machine from election | No | All | Any | Report | Yes | precincts + machines | 5% | No | Il. Rev. Stat. ch. 10 §5/24A-15, 10 §5/24C-15 | 13 | ||

| Ohio | Hand count | Yes | 3-President, random state-wide, random county-wide, in general elections in even-numbered years | 0.5% (0.2% if margin under 1%) | Expand sample. Sec. of State may order full recount of county | Yes | machines, precincts or polling places | at least 5% of votes | No | Secretary of State Directive 2014-36,[3] 2015 Election Official Manual | settlement agreement in League of Women Voters, et al. v. Brunner, Case No. 3:05-CV-7309, US N.District of Ohio | 12 | |

| Georgia | None | 0 | 10 | ||||||||||

| North Carolina | Hand count | Yes | 1-President or state-wide ballot item | "Significant" | Expand sample to whole county, all races | No | precincts | risk-limiting | No | No audit | N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §163-182.1 | 10 | |

| Michigan | None | 0 | 10 | ||||||||||

| New Jersey | None | 0 | N.J. Stat. Ann. §19:61-9 | 9 | |||||||||

| Virginia | Hand count | No | Some | Any | Analyze | Yes | localities | risk-limiting | No | Code of VA 24.2-671.1 | 8 | ||

| Washington | If parties agree or county auditor requires, then hand count sample of mail ballots, which are the vast majority | Maybe | 1 | Any | investigate + resolve | Yes | precincts or batches of mailed ballots | up to 3 precincts or 6 batches | No | Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §29A.60.185, §29A.60.170 | 7 | ||

| Arizona | Hand count | Yes | 5-President, random federal, random state-wide, random legislative, ballot measure | Statistical committee chooses cutoffs | Expand sample, up to whole county, for affected office | Yes | precincts | at least 2% or 2 | No | Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16-602 | 7 | ||

| Massachusetts | Hand count | Maybe | 6-President, state and national Senator and Representative, random ballot question | Cast doubt on outcome | Sec. of State may expand audit | Yes | precincts | 3% | Yes | Mass. Gen. Law Ann. ch. 54 § 109A | 7 | ||

| Tennessee | Count with same method as election day, different optical scanner | No | 1-President or Governor in general | 1% | Expand sample to 3% of precincts. Then no action, but audit is evidence in court | No | precincts | 1 to 5 | No | Tenn. Code Ann. § 2-20-103 | 7 | ||

| Indiana | If requested by party chair, hand count or machine different from voting system | Yes | All | No rules | Correct errors | No | precincts | up to 5% or 5 | No | Indiana Code §3-12-5-14, §3-11-13-39 | 7 | ||

| Missouri | Hand count | Maybe | 5-state-wide candidate + ballot issue, legislator, judicial, county | 0.50% | Investigate and resolve | Yes | precincts | 5% | No | 15 Mo. Code of State Regs. §30-10.110 | 6 | ||

| Maryland | Independent machines re-count ballot images from election machines[20] | Yes | All | Any | Investigate and resolve | Yes | All | 100% | No | Code of Md. Regs. §33.08.05 | 6 | ||

| Wisconsin | Hand count | No | 4-President or Governor, and 3 random state contests, only in general | Any | If no explanation, get manufacturer to investigate | Yes | wards or other districts reporting results | 100 per state | No | Wis. Stat. Ann. §7.08(6) | Wisconsin Elections Commission Voting Equipment Audits | 6 | |

| Colorado | Hand count | Maybe | In each county: 1 contest in general election, 1 per party in primary,[21][22] non-randomly chosen by Sec. of State | Statistical cutoffs | Investigate + decide | Yes | ballots | risk-limiting. 5% of machines, in sampled machines, 20% if machine has 1-500 ballots, otherwise lesser of 5% or 500 | No | Colo. Rev. Stat. §1-7-515 | Colo. Sec. of State Election Rule 25 | 6 | |

| Minnesota | Hand count | Yes | 2-3-Governor + federal | 0.5% or 2 votes | Expand samples for Governor + federal up to whole county, and if counties with 10% of state's ballots discover problems in a race, hand-count affected race statewide | Yes | precincts | 3% or at least 2-4 | No | Minn. Stat. Ann. §206.89 | 6 | ||

| South Carolina | None | 0 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Alabama | None | 0 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Louisiana | None | 0 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | None on paperless machines, which most counties use, hand count otherwise | Yes | All | No rules | Correct errors | Yes | precincts | 3% to 5% | No | Ky. Rev. Stat. §117.383 | 4 | ||

| Oregon | Hand count | Yes | 2-3-heaviest vote in each county, statewide office + ballot measure | 0.50% | Expand sample to whole county for that vote tally system, all races | Yes | precincts with 150 or more ballots | 3% to 10% depending on margin of victory | No | Or. Rev. Stat. §254.529 | 4 | ||

| Oklahoma | None | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Connecticut | Count with machines or by hand | Maybe | 3-President or Governor and 2 other races; 20% of races in primaries and municipal ballots | 0.50% | Investigate and if needed recount county with mix of hand and machine counts | Yes | voting districts | 5% | No | Conn. Gen. Stat. §9-320f | 4 | ||

| Iowa | Hand count | No | 1-President or Governor | No rules | Report | Yes | precincts | ? | No | HB 516, enacted in 2017 | 3 | ||

| Utah | Hand count | No | All | Any | Record reasons | Yes | machines | 1% | No | Election Policy Directive from the Office of the Lieutenant Governor | 3 | ||

| Arkansas | None | 0 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Nevada | Count with machines or by hand | Maybe | All | No rules | No rules | Yes | machines | 2% or 3% | No | Nev. Admin. Code 293.255, Nev. Rev. Stat. §293.247 | 3 | ||

| Mississippi | None | 0 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Kansas | None | 0 | 3 | ||||||||||

| New Mexico | Hand count | Yes | 3-4: federal, governor + closest statewide race | error over 90% of the margin of victory | Expand sample, up to whole state for affected office | Yes | precincts | none in race with over 15% margin of victory, otherwise 4-165 in state | No | N.M. Stat. Ann. §1-14-13.2 et seq. | 2 | ||

| Nebraska | If requested by Sec of State, method unclear | Maybe | 3 | Unclear | Report | Yes | precincts | 2% | Unclear | 2 | |||

| West Virginia | Hand count | Yes | All | 1% or changed outcome | Expand sample to whole county, all races | No | precincts | 3% | No | W. Va. Code, §3-4A-28 | 2016 Best Practices Guide for Canvass and Recount | 2 | |

| Idaho | None | 0 | Idaho Code §34-2313 | 2 | |||||||||

| Hawaii | Hand count | Maybe | 3-state-wide, county-wide, district-wide | Any | Expand audit until staff are satisfied with results | Yes | precincts | 10% | No | Hawaii Rev. Stat. §16-42, Haw. Admin. Rules § 3-172-102 | 1 | ||

| New Hampshire | None | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Maine | None | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Rhode Island | Hand count | Yes | Some | Statistical cutoffs | Expand sample to full recount | Rules not yet published | Not yet published | risk-limiting | Not yet published | R.I. Stat. Ann. §17-19-37.4 | 1 | ||

| Montana | Hand count | Yes | 4-random federal, state-wide, legislative, ballot measure | 0.5% or 5 votes | Expand sample but not full recount except in small counties with up to 6 precincts. Check machines with errors | Yes | precincts | at least 5% or 1 | No | Mont. Code Ann. §13-17-503 | 1 | ||

| Delaware | None | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| South Dakota | None | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | None | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Alaska | Hand count | Yes | All | 1% | Expand sample to whole district (1/40th of state), all races | Yes | large precincts | 1 per House district, with at least 5% of district ballots, so about 600 registered voters | No | Alaska Stat. §15.15.430 | 1 | ||

| District of Columbia | Hand count | Yes | 4-random District-wide, 2-ward-wide, 1 any type | 0.25% or 20% of margin of victory | Expand sample, up to whole county, for affected office | Yes | precincts + ballots | 5% | Yes | D.C. Code Ann. §1-1001.09a | 1 | ||

| Vermont | Each town counts with same method as election day, optical scan or hand count. Sec.of State randomly picks 6 towns to scan & machine-count all contests[23] | No | Unknown by county. All by Sec.of State | Any | Investigate | Yes | polling places | ? | No | 17 Vt. Stat. Ann. §2493, §2581 - §2588 | 1 | ||

| Wyoming | None | 0 | 1 |

Risk-limiting audits

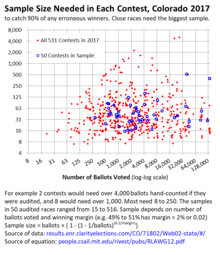

Risk-limiting audits are required in Colorado, North Carolina, Rhode Island and Virginia.[15] These choose random representative samples big enough to be sure results are accurate, up to an acceptable level of risk, such as 9%. For each audited race, if the original computer count identified the wrong winner, there is a 9%[22] chance in Colorado that the audit will miss it,[24] and the wrong winner will take office. A lower risk limit would let fewer errors through, but would require larger sample sizes. Close races also require larger sample sizes. Colorado audits only a few races, and audits none of the closest races, which need the biggest samples. Auditing all races would require several counties to hand-count thousands of ballots each.

If the samples do not confirm the initial results, more rounds of sampling may be done, but if it appears the initial results are wrong, risk-limiting audits require a 100% hand count to change the result, even if that involves hand-counting hundreds of thousands of ballots.[25]

Colorado notes that they have to be extremely careful to keep ballots in order, or they have to number them, to be sure of comparing the hand counts with the machine records of those exact ballots.[26] Also they have to re-tally all the machine records, independently of the election software, to be sure the machine records they audit generate all the same winners reported by the election software. Colorado says it has a reliable system to re-tally the records, but it is not yet publicly documented.[27] [24]

In 2010, the American Statistical Association endorsed risk-limiting audits, to verify election outcomes.[28] With use of statistical sampling to eliminate the need to count all the ballots, this method enables efficient, valid confirmation of the outcome (the winning candidates). In 2011, the federal Election Assistance Commission initiated grants for pilot projects to test and demonstrate the method in actual elections.[29] In 2014, the Presidential Commission on Election Administration recommended the method for use in all jurisdictions following all elections, to reduce the risk of having election outcomes determined by undetected computer error or fraud.[30] In 2017, Colorado became the first state to implement risk-limiting audits statewide as a routine practice during the post-election process of certifying election results.

Ballot scans for 100% audits

Humboldt County, CA, Clear Ballot, and TrueBallot scan all ballots with a commercial scanner, so extensive audits can be done on the scans without damaging paper ballots, without hand-counting, by multiple groups, independently of the election software.[31] Clear Ballot is certified by the US Election Assistance Commission for voting,[32] and they also have an auditing system, ClearAudit. TrueBallot does not currently serve government elections, just private groups. Both use proprietary software, so if it were hacked at the vendor or locally to create false images of the ballots or false counts, then local officials and the public could not check it.

The most open audit system is the Elections Transparency Project, as used in Humboldt County, California, a medium sized county with 58,000 ballots in the 2016 general election.[33] They use a commercial scanner to scan all ballots and put them in a digitally signed file, so true copies of the file can be reliably identified. Ballots with identifying marks are first hand-copied by election staff, to anonymize them, since they are valid under California law.[34] The scanner prints a number on each ballot before scanning it, so the scan can be checked against the same physical ballot later if needed.

The project has written open source software to read the files, and they check all races on all ballots to see if official counts are correct. The first time they scanned and checked, in 2008, they found 200 missing ballots, showing the value of complete checks.[35] Other jurisdictions can similarly scan ballots and use Humboldt's software or their own to audit all races. They need to ensure their in-house counting software is secure and independent of any bugs or hacks in the election software, just as users of risk-limiting audits do.

Reading these scans, with software independent of the election system, is the only practical way to audit a large number of close races, without large hand counts. If scanned on election night, scans are also the only practical way to bypass problems of physical security, since scans are made and digitally signed before ballots are stored, while other audit methods are too slow to do election night. Scanners can process thousands of ballots per hour, and several scanners can operate simultaneously in larger jurisdictions. Once ballots are scanned with a digital signature, they can be analyzed at any convenient time.

Humboldt has gone beyond this internal approach, and decided to release the digitally signed files of ballot images to the public, so others can use their own software, independent of the election system and officials, to check all races on all ballots.[36] [37] [38] Public release lets losing candidates who mistrust the election officials' security measures do their own checks. Humboldt County believes the scans give their citizens high confidence in the county election results.[36]

The "Brakey method" is a variant of the Humboldt scans, with a public release of electronic ballot images already created by most current US election systems.[39]. The Brakey Method requires that the ballot images be connected to their physical ballots through a unique identifier that appears on both digital image and physical ballot. Because ballot images can be hacked if the election software itself is hacked,[40] either at the vendor or elsewhere, ballot images do not provide an independent check unless they can be compared with physical ballots.

Pennsylvania uses these ballot images for its audits,[15] though it does not release them to the public for the public to audit.

Other variations

Hand and machine counts. Current audits in most states involve counting paper ballots by hand, but some states re-use the same machines used in the election. Three states use different machines, to provide some independent check.

Sample sizes. When states audit, they usually pick a random sample of 1% to 10% of precincts to recount by hand or by machine. If a precinct has more than one machine, and they keep ballots and totals separate by machine, they can draw a sample of machines rather than precincts and count all ballots processed by that machine. These samples can identify systematic errors widely present in the election. They have only a small chance of catching a hack or bug which was limited to a few precincts or machines, even though that could change the result in close races.

Number of races. In the random sample, most states audit only a few races, so they can only find problems in those races.

Physical security. Auditing is done several days after the election, so paper ballots and computer files need to be kept securely. North Carolina specifies that no audit is done if ballots are missing or damaged.[15]

Physical security has its own large challenges. No US state has adequate laws on physical security of the ballots.[41] Security recommendations for elections include: starting audits as soon as possible after the election, preventing access by anyone alone,[42] having risks identified by people other than those who design or manage the storage, using background checks and tamper-evident seals.[43][25] However seals on plastic surfaces can typically be removed and reapplied without damage.[44] [40]

Experienced testers can usually bypass all physical security systems. Security equipment is vulnerable before and after delivery. Insider threats and the difficulty of following all security procedures are usually under-appreciated, and most organizations do not want to learn their vulnerabilities.[45]

References

- ↑ Report on Election Auditing, Election Audits Task Force of the League of Women Voters of the United States, January 2009. Accessed May 12, 2017.

- ↑ Post-election Audits, Verified Voting Foundation, undated. Accessed May 12, 2017.

- ↑ Some Machines are Flipping Votes, but That Doesn’t Mean They Are Rigged, Pam Fessler, National Public Radio, October 26, 2016. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ The Machinery of Democracy: Protecting Democracy in an Age of Electronic Voting, Brennan Center Task Force for Voting System Security, 2006.

- ↑ Brave New Ballot: The Battle to Safeguard Democracy in the Age of Electronic Voting, Aviel David Rubin, Broadway, 2006

- ↑ Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count? Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simon, CSLI Publications, 2012

- ↑ Voting Equipment Certification Process, US Election Assistance Commission.

- ↑ Pre-election and Parallel Testing, U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

- ↑ Elections Performance Index Methodology, Pew Charitable Trusts, August 2016. Accessed May 12, 2017.

- ↑ Confidence in the Electoral System: Why We Do Auditing, Michael W. Trautgott and Frederick G. Conrad, in Confirming Elections: Creating Confidence and Integrity Through Election Auditing, R. Michael Alvarex, Lonna Rae Atkeson, and Thad E. Hall, eds., Palgrave MacMillan, 2012.

- ↑ The Front Lines of Democracy: Who Staffs our Polling Places and Does it Matter? Bonnie E. Glaser, Karin MacDonald, Iris Hui, and Bruce E. Cain; Election Administration Research Center, University of California at Berkeley. October 2007

- ↑ Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count? Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simon, CSLI Publications, 2012

- ↑ As of early 2018, Colorado is the only state that has made valid, outcome-confirming election audits routine following all elections.

- ↑ Counting Votes 2012: A State by State Look at Voting Technology Preparedness, Pamela Smith, Verified Voting Foundation; Michelle Mulder, Rutgers School of Law-Newark; Susannah Goodman, Common Cause Education Fund, 2012. Accessed May 12, 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 "State Audit Laws". Verified Voting. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures. "Post-Election Audits". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ US Census Bureau. "State Population Totals: 2010-2017". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ Steinberg, Sean (2017-10-30). "New California Law Strikes Blow to Election Audits - WhoWhatWhy". WhoWhatWhy. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Post Election Manual Tally Audit Summary Information" (PDF). calvoter.org/issues/votingtech/manualcount.html. 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Lamone, Linda (2016-12-22). "Joint Chairman's Report on the 2016 Post-Election Tabulation Audit" (PDF). Maryland State Board of Elections. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ↑ Casias, Danny (2017-11-08). "Audited contests in each county for 2017 RLA (XLSX)". www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/auditCenter.html. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- 1 2 "Round #1 State Report". www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/auditCenter.html. 2017-11-20. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Secretary of State Jim Condos to Conduct Election Audit". www.vermont.gov. 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- 1 2 Stark, Philip (2012-03-16). "Gentle Introduction to Risk-limiting Audits" (PDF). IEEE Security and Privacy – via University of California at Berkeley, pages 1, 3.

- 1 2 Lindeman, Mark (executive editor), Jennie Bretschneider, Sean Flaherty, Susannah Goodman, Mark Halvorson, Roger Johnston, Ronald L. Rivest, Pam Smith, Philip B. Stark (2012-10-01). "Risk-Limiting Post-Election Audits: Why and How" (PDF). University of California at Berkeley. pp. 3, 16. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ Lovato, Jerome, Danny Casias, and Jessi Romero. "Colorado Risk-Limiting Audit:Conception to Application" (PDF). Bowen center for Public Affairs and Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Lindeman, Mark, Ronald L. Rivest, Philip B. Stark and Neal McBurnett (2018-01-03). "Comments re statistics of auditing the 2018 Colorado elections" (PDF). Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ Statement on Risk-limiting Auditing, American Statistical Association, April 2010. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ Post-Election Risk-Limiting Audit Pilot Program 2011-2013, Final Report to the United States Election Assistance Commission, California Secretary of State 2013. Accessed May 12, 2017

- ↑ The American Voting Experience: Report and Recommendations of the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, January 2014

- ↑ Stark, Philip B. (2010). "Super-Simple Simultaneous Single-Ballot Risk-Limiting Audits". Proceedings of the 2010 Electronic Voting Technology Workshop / Workshop on Trustworthy Elections – via (EVT/WOTE ’10). USENIX.

- ↑ "Voting System, US Election Assistance Commission". www.eac.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

- ↑ "California Supplement to the Statement of Vote, Statewide Summary by County for President" (PDF). sos.ca.gov/elections/prior-elections/statewide-election-results/general-election-november-8-2016/statement-vote/. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "California Code, Elections Code - ELEC § 15154". Findlaw. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Zetter, Kim (2008-12-08). "Unique Transparency Program Uncovers Problems with Voting Software". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- 1 2 "The Elections Transparency Project". The Elections Transparency Project. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Mitch. "Humboldt County Election Transparency Project" (PDF). San Francisco Elections Commission. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Mitch (2013-07-29). "The Humboldt County Election Transparency Project and TEVS" (PDF). Report for Elections Advisory Commission. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ "Actions: The Brakey Method". BlackBoxVoting.org. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- 1 2 Stauffer, Jacob (2016-11-04). "Vulnerability & Security Assessment Report Election Systems &Software's Unity 3.4.1.0" (PDF). Verified Voting. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Benaloh, Public Evidence from Secret Ballots; et al. (2017). Electronic voting : second International Joint Conference, E-Vote-ID 2017, Bregenz, Austria, October 24-27, 2017, proceedings (PDF). Cham, Switzerland. p. 122. ISBN 9783319686875. OCLC 1006721597.

- ↑ Lindeman, Mark, Mark Halvorson, Pamela Smith, Lynn Garland, Vittorio Addona, Dan McCrea (2008-09-01). "Best Practices: Chain of Custody and Ballot Accounting, ElectionAudits.org" (PDF). Brennan Center for Justice et al. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ "Chapter 3. PHYSICAL SECURITY" (PDF). US Election Assistance Commission. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Coherent Cyber, Freeman, Craft McGregor Group (2017-08-28). "Security Test Report ES&S Electionware 5.2.1.0" (PDF): 9 – via California Secretary of State.

- ↑ Seivold, Garett (2018-04-02). "Physical Security Threats and Vulnerabilities - LPM". losspreventionmedia.com. Retrieved 2018-04-24.