Right of abode (United Kingdom)

The right of abode is a status under United Kingdom immigration law that gives an unrestricted right to live in the United Kingdom. It was introduced by the Immigration Act 1971.

History of right of abode before 1983

Prior to the enactment of British Nationality Act 1981, right of abode in the UK was mainly determined by a mix of one's connection with the UK and their nationality status.

The following two categories of persons had right of abode:[1]

- Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs)

CUKCs who met any of the following requirements acquired right of abode between 1973 to 1983.

- born in a part of the British Islands (note that birth in the UK or the islands would automatically confer CUKC status in most circumstances);

- born to or legally adopted by a CUKC parent born in the British Islands;

- born to or legally adopted by a parent who, in turn, was born to or legally adopted by a CUKC parent born in the British Islands;

- had settled in the British Islands for at least five years;

- was a female CUKC married to a CUKC man with right of abode.

- Commonwealth citizens

Any Commonwealth citizens who met one of the requirements below would also acquire right of abode between 1973 and 1983.

- born to or legally adopted by a CUKC parent born in the British Islands (note that this provision primarily applied to persons born to UK-born CUKC mothers as women could not pass down CUKC status)

- was a female Commonwealth citizen married to a CUKC man who had right of abode.

Right of abode was limited to CUKCs and Commonwealth citizens, therefore certain people with connections to the UK were not eligible. For example, a person born to a UK-born CUKC mother and a non-Commonwealth citizen father in the United States would not acquire right of abode as they possessed neither CUKC status nor Commonwealth citizenship. However, the same person born in Canada would obtain right of abode due to Canada's membership in the Commonwealth.

CUKCs with right of abode would in 1983 become British citizens, whereas Commonwealth citizens' nationality status remained unchanged. However, any person who had voluntarily or involuntarily lost their CUKC status (or Commonwealth citizenship) between 1973 and 1983 would also lose their right of abode.

The introduction of the right of abode principle effectively created two tiers of CUKCs: those with right of abode and those without right of abode, both of which shared the same nationality status until 1983. The latter group would become either British Dependent Territories citizens or British Overseas citizens that year, depending on whether they had a connection with a British Dependent Territory.

Acquisition of the right of abode

Since 1983, right of abode is established by the British Nationality Act 1981 and subsequent amendments, although the 1981 Act did not deprive any person's right of abode providing that they had retained the right on 31 December 1982.

Two categories of persons hold right of abode:

- British citizens

All British citizens have the right of abode in the British Islands.

- Commonwealth citizens and British subjects who retained their right of abode prior to 1983

Right of abode is also retained by a Commonwealth citizen or a British subject who, on 31 December 1982:

- had a parent who, at the time of the person's birth or legal adoption, was a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies on account of having been born in the UK; or

- was a female Commonwealth citizen or British subject who was, or had been, married to a man who had the right of abode.

For this purpose, the UK includes the Republic of Ireland prior to 1 April 1922.

No person born in 1983 or later can have the right of abode unless he or she is a British citizen.

It is essential that the person concerned should have held Commonwealth citizenship or British subject status on 31 December 1982 and has not ceased to be a Commonwealth citizen (even temporarily) after that date. For this reason, citizens of Pakistan and South Africa are generally not entitled to the right of abode in the UK as these countries were not Commonwealth members on 1 January 1983. Citizens of Fiji and Zimbabwe are still considered to be Commonwealth citizens (for nationality purposes) even after the two countries' withdrawal from the Commonwealth because the UK has not amended Schedule 3 to the British Nationality Act 1981.

A woman claiming the right of abode through marriage will cease to qualify if another living wife or widow of the same man:

- is (or has been at any time since her marriage) in the UK, unless she entered the UK illegally, as a visitor, or with temporary permission to stay; or

- has been given a certificate of entitlement to right of abode or permission to enter the country because of her marriage.

However, this restriction does not apply to a woman who:

- entered the UK as a wife before 1 August 1988, even if other wives of the same man are in the UK; or

- who has been in the UK at any time since her marriage, and at that time was that man's only wife to have entered the UK or to have been given permission to do so.

Multiple claims

An individual may be able to claim the right of abode in the United Kingdom through more than one route. For example, a woman who was a New Zealand citizen and married to a British citizen on 31 December 1982, and who subsequently moves to the UK with her husband and naturalises as British citizen can claim the right of abode in the UK both through her British citizenship and through her status as a Commonwealth citizen who was married to a British citizen on 31 December 1982. Therefore, if she were to renounce her British citizenship, she would still be allowed to stay in the UK free from any immigration restrictions. However, if she were to renounce her New Zealand citizenship, she would permanently lose her ability to claim a right of abode through her Commonwealth citizenship and marriage to a British citizen on 31 December 1982, and would only be able to claim a right of abode through her British citizenship.

Proof of the right of abode

The only legally recognised documents proving an individual's right of abode in the UK are the following:[2]

- a British passport describing the holder as a British citizen or as a British subject with the right of abode

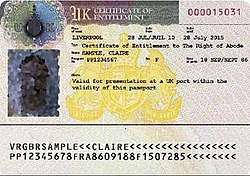

- a certificate of entitlement to the right of abode in the UK, which has been issued by the UK government or on its behalf

An individual who has the right of abode in the UK but does not have or is ineligible for such a British passport can apply for a certificate of entitlement to be affixed inside his/her other passport or travel document.

For example, a US citizen who has naturalised as a British citizen can apply for a certificate of entitlement to be affixed inside his or her US passport to prove that he or she is free from immigration restrictions in the UK, rather than obtaining a British passport. A British Overseas Territories Citizen from the British Virgin Islands who is also a British citizen can apply for a certificate of entitlement to be affixed inside his or her British Virgin Islands passport to prove that he or she is free from immigration restrictions in the UK, rather than obtaining a British citizen passport. In contrast, a New Zealand citizen who has right of abode but does not have a form of British nationality must hold a valid certificate of entitlement in their New Zealand passport in order to be exempt from immigration control in the UK, otherwise they will be treated as subject to immigration control by UK Border Force officers at a port of entry.

A certificate of entitlement costs £272 when issued in the UK and £472 when issued outside the UK.[3] This is considerably more expensive than obtaining a British passport (£77.50 for a 10-year adult passport, £49 for a 5-year child passport and free for a 10-year passport for those born on or before 2 September 1929 when issued inside the UK; £128 for a 10-year adult passport, £81.50 for a 5-year child passport and free for a 10-year passport for those born on or before 2 September 1929 when issued outside the UK).

Rights and privileges of the right of abode

All individuals who have the right of abode in the United Kingdom (regardless of whether they are a British citizen, British subject or Commonwealth citizen) enjoy the following rights and privileges:

- an unconditional right to live, work and study in the United Kingdom

- an entitlement to use the British/EEA immigration channel at United Kingdom ports of entry

- an entitlement to apply for United Kingdom social security and welfare benefits (although those with indefinite leave to enter may also apply)

- a right to vote and to stand for public office in the United Kingdom (since everyone with the right of abode is a Commonwealth citizen; these rights are conditional upon living in the United Kingdom).

In addition, those with the right of abode who are not yet British citizens may apply for British citizenship by naturalisation (or registration for other categories of British nationals) after meeting the normal residence and other requirements. Children born in the United Kingdom, British Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories to those with right of abode in the UK will normally be British citizens by birth automatically.

Other United Kingdom immigration concessions

United Kingdom immigration laws allow settlement to other categories of persons; however, although similar in practice these do not constitute a formal right of abode and the full privileges of the right of abode are not necessarily available.

Irish citizens and the Common Travel Area

Before 1949, all Irish citizens were considered under British law to be British subjects.[4] After Ireland declared itself a republic in that year, a consequent British law gave Irish citizens a similar status to Commonwealth citizens in the United Kingdom, notwithstanding that they had ceased to be such. Unlike Commonwealth citizens, Irish citizens have generally not been subject to entry control in the United Kingdom and, if they move to the UK, are considered to have 'settled status' (a status that goes beyond indefinite leave to remain). They may be subject to deportation from the UK upon the same lines as other European Economic Area nationals.[5] In February 2007 the British government announced that a specially lenient procedure would apply to the deportation of Irish citizens compared to the procedure for other European Economic Area nationals.[6][7] As a result, Irish nationals are not routinely considered for deportation from the UK when they are released from prison.[8]

EU, EEA, and Swiss nationals in the UK

In the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2006,[9] the United Kingdom declared that most citizens of EEA member states and their family members should be treated as having only a conditional right to reside in the UK. This has implications should such a person wish to remain permanently in the United Kingdom after ceasing employment, claim social assistance, apply for naturalisation or acquire British citizenship for a UK-born child.

Those EU/EEA/Swiss nationals who will be treated as permanent residents of the UK include:

- certain persons who have retired from employment or self-employment in the UK and their family members

- those who have been granted permanent residence status (normally acquired after five years in the UK)

- Irish citizens (because of the Common Travel Area provisions)

These persons remain liable to deportation on public security grounds.

Indefinite leave to remain

Indefinite leave to remain is a form of UK permanent residence that can be held by non-EU/EEA/Swiss citizens, but it does not confer a right of abode.

British Overseas Territories

All British overseas territories operate their own immigration controls, which apply to British citizens as well as to those from other countries. These territories generally have local immigration laws regulating who has belonger status in that territory.

See also

References

- ↑ S2 of 1971 c.77

- ↑ GOV.UK: Right of abode

- ↑ GOV.UK: Apply for a certificate of entitlement

- ↑ Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, William Ormsby-Gore, House of Common Debates volume 167 column 24 (23 July 1923): "All the people in Ireland are British subjects, and Ireland under the Constitution is under Dominion Home Rule, and has precisely the same powers as the Dominion of Canada, and can legislate, I understand, on matters affecting rights and treaties." ;

Hachey, Thomas E.; Hernon, Joseph M.; McCaffrey, Lawrence John (1996). The Irish experience: a concise history (2nd ed.). p. 217.The effect of the [British Nationality Act 1948] was that citizens of Éire, though no longer British subjects, would, when in Britain, be treated as if they were British subjects.

- ↑ See Evans.

- ↑ Minister of State for Immigration, Citizenship and Nationality, Liam Byrne, House of Lords Debates volume 689 Column WS54 (19 February 2007) .

- ↑ "Irish exempt from prisoner plans". British Broadcasting Corporation. 19 February 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Justice, Jeremy Wright, House of Commons Debates Column 293W (5 February 2014) .

- ↑ http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/2326/contents/made