Richard Henry Park

| Richard Henry Park | |

|---|---|

| Born |

February 17, 1832 Hebron, Connecticut |

| Died |

1902 Battle Creek, Michigan |

| Occupation | Sculptor |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Richard Henry Park (also Richard Hamilton Park; February 17, 1832 – 1902) was an American sculptor who worked in marble and bronze. He was commissioned to do work by the wealthy of the nineteenth century. He also created sculptures for the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.

Life and career

Park was born February 17, 1832, in Hebron, Connecticut.[1] He was inspired by a Hiram Powers exhibition to become a sculptor.[2] From 1855, Park worked in the Albany, New York studio of Erastus Dow Palmer, the foremost neoclassical sculptor of his time,[3] starting out as a marble cutter's apprentice making marble copies of Palmer's work. He stayed until 1861, working as an assistant to Palmer[3] alongside other future sculptors Launt Thompson[4] and Charles Calverley.[5] He moved to New York city to establish an independent career before moving to Florence, Italy around 1871.[6] Park's early work was in marble, later changing to the medium of bronze for natural sculptures, in line with the American trend for late nineteenth century sculptures.

During his time in Florence, Park was commissioned to prepare a marble bust of John Plankinton, an astute businessman who founded the meat industry in Wisconsin and was respected as "Milwuakee's foremost citizen". Plankinton was known for religious convictions, his success from a modest upbringing, and for his regular philanthropic public deeds; he became known as "A Merchant Prince and Princely Merchant".[7] Plankinton's daughter, Elizabeth, travelled to Europe in 1879, and met Park in Florence. On return to Milwaukee, Elizabeth convinced her father to let her commission Park to sculpt the first piece of public art for Milwaukee, a monument to George Washington.[8] Park worked on the monument to Washington in Florence, and it was completed and shipped to Milwaukee for its dedication in November 1885;[9][10] Elizabeth donated it to the city of Milwaukee as a philanthropic gesture.[8] At some point, Park and Elizabeth Plankinton became engaged, and in 1886 John Plankinton commenced construction on a mansion to be a wedding gift for his only daughter.[11] On 18 September 1887, Park married another woman,[12] a dancer from Minneapolis,[10] shortly after his Juneau Monument (in recognition of Milwaukee's first Mayor, Solomon Juneau) was dedicated.[13] When Elizabeth learned of Park's marriage, she left on a long trip to Europe. On her return, she took her only look at the mansion her father had built, and is said never to have set foot in it again.[14]

Park made an over-life-size bronze monument statue as a tribute to the 21st Vice President of the United States, Thomas A. Hendricks. It was unveiled in 1890 on the grounds at the Indiana State House in Indianapolis. After this he moved his studio to Chicago to get commissions in the sculptural programs for the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.[6] He met Lee Lawrie in Chicago and Lawrie went on to work as Park's apprentice and assistant (1891-1894). One of the monuments they worked on was an over-life-size all silver monument statue for the state of Montana titled Justice that was exhibited in the Mines and Mining Building. It was rumoured to have been melted down later for the silver. There is an 1893 medal showing the model that posed for the statue on its reverse side.[6] It has been suggested that Park's most enduring legacy may be his role as mentor and teacher to Lawrie.[15]

Remarkably, given his history with the family, Park spent six months in Chicago working on a statue of John Plankinton following his 1891 death, commissioned by William Plankinton, Elizabeth's brother. Described as a "handsome bronze statue", it was unveiled on 29 June 1892 and "viewed by hundreds of people, the great majority of whom pronounced it one of the most lifelike statues of Uncle John Plankinton possible to be executed."[16] It stood in the Plankinton House Hotel until the location was redeveloped in 1915 into a shopping district, Plankinton Arcade, which incorporated a rotunda in which the statue was placed. The statue underwent several months of restoration work in 2012, before returning to its place in the rotunda that is now a part of The Grand shopping plaza.[16][17][18]

One of the bronze statues Park made for the Fair was of Benjamin Franklin and it was three years later reinstalled at Lincoln Park in downtown Chicago.[19] An 1895 review of the public monuments in Milwaukee listed five existing pieces, two sculpted by Park.[20] He is best known for his Actor's Monument to Edgar Allan Poe (1884) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York city, and the Drake Fountain in Chicago (1892).

Author and art historian Lauritta Dimmick records that Park died in 1902 in Battle Creek, Michigan,[6] although there are others who believe he died in New York City.[21] Dimmick's view is confirmed by his obituary in the Chicago Tribune dated November 8, 1902, which states he died "at the "Battle Creek sanitarium."

Works by Park

Milwaukee's Court of Honor

Washington monument, 1885

Motivated by her love for Milwaukee,[22] Elizabeth Plankinton commissioned Park to prepare a monument to George Washington as Milwaukee's first piece of public art,[8] at a cost of around $20,000[23] (equivalent to $0.5 million in 2016).[24] It was unveiled and dedicated in November 1885.[9][10] Washington is portrayed in uniform as the 43-year-old commander-in-chief of the Continental Army,[8] and stands 9 feet 2 inches (2.79 m) tall on a 12 feet 1 inch (3.68 m) granite base.[23] The bronze figures of a mother and child at the base of the monument were included at the request of Plankinton. With substantial immigration to Milwukee occurring, Plankiton wanted a child being shown the father of the United States portrayed[8] to symbolise the importance of history. As one speaker at the dedication put it, "during the coming generations when other men shall walk these streets, this monument will stand a text for the old and a lesson for the young."[22] The monument was described in 1895 in The Monumental News as "classical to the verge of conventionality."[25] The statue was moved to Illinois in mid-2016 for restoration work due to ongoing corrosion.[26] During the move, restorer Andrzej Dajnowski discovered major cracking in one of the legs and that the sculpture's sword might not be the original.[8] The restoration is expected to be completed by mid-2017 and to cost around $100,000.[26]

Juneau Monument, 1887

Solomon Juneau was a key figure in the early history of Milwaukee, having been the area's first white settler and the first Mayor of the city.[13] Park's Juneau Monument is the most prominent object in the Milwaukee park built in Juneau's honour, where it stands on a bluff overlooking Lake Michigan.[25] The monument cost around $25,000 (equivalent to $0.6 million in 2016)[24] and was gifted to the city by Charles T. Bradley and William H. Metcalf on behalf of their shoe company.[27] It was unveiled on 6 July 1887, and was described by the Milwaukee Sentinel newspaper as "a credit to the artist and the city, as well as a monument to the public spirit of the donors."[28] The bronze statue is over-life-sized, standing 13 feet (4.0 m) tall above a 31 feet (9.4 m) base of red granite,[27] and depicts Juneau "clothed in the habit of the pioneer"[28] and carrying a rifle. Two sides of the pedestal feature bronze bas-relief scenes from Juneau's life while the other two sides feature inscriptions. Strong similarities have been noted between the sculpture's visage and that of Park's Washington statue.[13] Accentuating this similarity is the relief scene of Juneau's inauguration as Mayor – described as perhaps the monument's best feature – where a bust of Washington is placed behind the Mayor's chair.[25]

Gallery

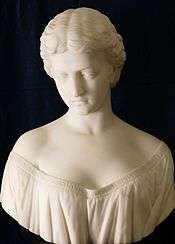

1879 Prof R • H • Park

- Mary Jane Seamans

(Mrs. Erastus Palmer)

c. 1860-1870 in marble  La Penserosa

La Penserosa

(shoe is not part of

original sculpture)

Thomas A. Hendricks Monument, circa 1890

Thomas A. Hendricks Monument, circa 1890- Ben Franklin Monument

Lincoln Park (Chicago)[19]

See also

References

- ↑ U.S. passport issued April 4, 1872

- ↑ Clark & Gerdts 1997, p. 225.

- 1 2 Dimmick 1999a, pp. 155-157.

- ↑ Dimmick 1999b, pp. 158-165.

- ↑ Tolles 1999, pp. 166-171.

- 1 2 3 4 Dimmick 1999a, p. 155.

- ↑ WMIHoF 1995, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bence 2016.

- 1 2 Israel 1933.

- 1 2 3 HS 2009.

- ↑ UWML 2003.

- ↑ Record #175 in marriages in the county of Ottawa, Michigan

- 1 2 3 TMN 1895, p. 22.

- ↑ Ackerman 2004, p. 105.

- ↑ Clark & Gerdts 1997, p. 227.

- 1 2 Stingl 2012.

- ↑ Romell 2012.

- ↑ Davis 2012.

- 1 2 Selzer 2014, p. 236.

- ↑ TMN 1895, p. 22-24.

- ↑ askArt 2017.

- 1 2 Buck & Palmer 1995, p. 53.

- 1 2 SIRIS 1994.

- 1 2 Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved January 5, 2018. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- 1 2 3 TMN 1895, p. 23.

- 1 2 Schumacher 2016.

- 1 2 SIRIS 1993.

- 1 2 MS 1887.

Sources

Books and journals

- Ackerman, Sandra (2004). Milwaukee Then and Now. Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 978-1-59223-203-1.

- Buck, Diane M.; Palmer, Virginia A. (1995). Outdoor Sculpture in Milwaukee: A Cultural and Historical Guidebook. State Historical Society of Wisconsin. ISBN 0-87020-276-6.

- Clark, Henry N. B.; Gerdts, William H. (1997). "Richard Henry Park". A Marble Quarry: The James H. Ricau Collection of Sculpture at the Chrysler Museum of Art. Hudson Hills Press in association with the Chrysler Museum of Art. ISBN 9781555951313.

Confusion even exists about where he was born, with both New York and Connecticut listed.

- Haught, R. J., ed. (1895). "The Monuments of Milwaukee" (PDF). The Monumental News. R. J. Haight (Editor and Publisher). 7 (1): 22–24.

- Selzer, Adam (2014). Chronicles of Old Chicago: Exploring the History and Lore of the Windy City. Museyon, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9846334-8-7.

- Tolles, Thayer, ed. (1999). A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born Before 1865. American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 978-0-8709991-4-7,

specifically the following chapters:

- Dimmick, Lauretta (1999a). Richard Henry Park (1832–1902). pp. 155–157.

- Dimmick, Lauretta (1999b). Charles Calverly (1833–1914). pp. 158–165.

- Tolles, Thayer (1999). Launt Thompson (1833–1894). pp. 166–171.

Newspaper and web

- "Richard Park (1832-1902)". askArt. 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Bence, Susan (18 July 2016). "Milwaukee's Oldest Monument Leaves City for Repair". WUWM Milwaukee Public Radio. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- Davis, Stacey Vogel (18 December 2012). "John Plankinton back at his post at Grand Avenue". Milwaukee Business Journal. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Elizabeth Plankinton House in Milwaukee, Wisconsin". historic-structures.com. 19 November 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

She was to have been married to Richard Hamilton Park, the British sculptor of the [bronze statue of George Washington which stands in the court of honor (West Wisconsin Avenue between North 9th and North 11th Streets)], but was deserted in favor of a dancer from Minneapolis. Totally distraught, she completely rejected her wedding gift house and was never to occupy it.

- Israel, Herbert M. (12 June 1933). "Famous Milwaukee Women". Wisconsin News. Retrieved 10 January 2017, which is also available from the Wisconsin Historical Society website.

- Milwaukee Sentinel (10 July 1887). "Solomon Juneau: Statue of the First White Settler of Milwaukee Unveiled" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

From the Milwaukee Sentinel, July 7.

- Romell, Rick (15 August 2012). "Statue of early industrialist John Plankinton to go into storage for a few months". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Schumacher, Mary Louise (July 8, 2016). "George Washington statue will cross the border Monday for restoration". The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- "Solomon Juneau, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Art Inventories Catalog, Smithsonian American Art Museum. May 1993. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- "George Washington, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Art Inventories Catalog, Smithsonian American Art Museum. January 1994. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- Stingl, Jim (22 September 2012). "Statue's history put to rights by sleuthing". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Wisconsin Avenue (Grand Avenue), E.A. Plankinton House". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. 23 May 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Wisconsin Meat Industry Hall of Fame, 1995 – John Plankinton" (PDF). University of Wisconsin-Madison. 1995. pp. 33–35. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Henry Park. |