Respiratory tract infection

| Respiratory tract infection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conducting passages | |

| Classification and external resources |

Respiratory tract infection (RTI) refers to any of a number of infectious diseases involving the respiratory tract. An infection of this type is normally further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tract infection (LRI or LRTI). Lower respiratory infections, such as pneumonia, tend to be far more serious conditions than upper respiratory infections, such as the common cold.

Types

Upper respiratory tract infection

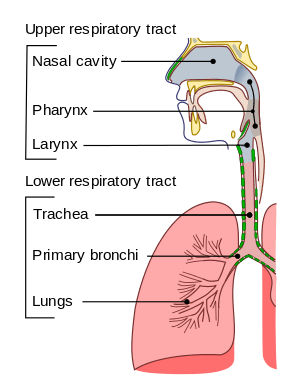

Although some disagreement exists on the exact boundary between the upper and lower respiratory tracts, the upper respiratory tract is generally considered to be the airway above the glottis or vocal cords. This includes the nose, sinuses, pharynx, and larynx.

Typical infections of the upper respiratory tract include tonsillitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, certain types of influenza, and the common cold.[1] Symptoms of URIs can include cough, sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, headache, low grade fever, facial pressure and sneezing.

Lower respiratory tract infection

The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea (wind pipe), bronchial tubes, the bronchioles, and the lungs.

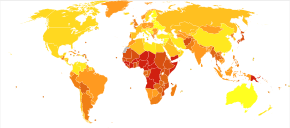

Lower respiratory tract infections are generally more serious than upper respiratory infections. LRIs are the leading cause of death among all infectious diseases.[2] The two most common LRIs are bronchitis and pneumonia.[3] Influenza affects both the upper and lower respiratory tracts, but more dangerous strains such as the highly pernicious H5N1 tend to bind to receptors deep in the lungs.[4]

Diagnosis

A 2014 systematic review of clinical trials does not support using routine rapid viral testing to decrease antibiotic use for children in emergency departments.[5] It is unclear if rapid viral testing in the emergency department for children with acute febrile respiratory infections reduces the rates of antibiotic use, blood testing, or urine testing.[5] The relative risk reduction of chest x-ray utilization in children screened with rapid viral testing is 77% compared with controls.[5] In 2013 researchers developed a breath tester that can promptly diagnose lung infections.[6][7]

Prevention

Despite superior filtration capability of N95 filtering facepiece respirators measured in vitro, insufficient clinical evidence has been published to determine whether normal surgical masks and N95 filtering facepiece respirators are equivalent with respect to preventing respiratory infections in healthcare workers.[8]

References

- ↑ Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, et al. (2007). "Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: identifying factors predictive of managing upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics". Implement Sci. 2: 26. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-26. PMC 2042498. PMID 17683558.

- ↑ Robert Beaglehole...; et al. (2004). The World Health Report 2004 - Changing History (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 120–4. ISBN 92-4-156265-X.

- ↑ Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Antibiotic. 13th ed. North Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2006.

- ↑ van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, et al. (April 2006). "H5N1 Virus Attachment to Lower Respiratory Tract". Science. 312 (5772): 399. doi:10.1126/science.1125548. PMID 16556800.

- 1 2 3 Doan, Quynh; Enarson, Paul; Kissoon, Niranjan; Klassen, Terry P.; Johnson, David W. (2014-09-15). "Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD006452. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006452.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25222468.

- ↑ "Breath Test Could Sniff Out Infections in Minutes". Scientific American. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Zhu, Jiangjiang; Bean, Heather D; Wargo, Matthew J; Leclair, Laurie W; Hill, Jane E (2013). "Detecting bacterial lung infections:in vivoevaluation ofin vitrovolatile fingerprints". Journal of Breath Research. 7 (1): 016003. doi:10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/016003. PMC 4114336. PMID 23307645.

- ↑ Smith, JD; MacDougall, CC; Johnstone, J; Copes, RA; Schwartz, B; Garber, GE (17 May 2016). "Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks in protecting health care workers from acute respiratory infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 188 (8): 567–74. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150835. PMC 4868605. PMID 26952529.