Red Hill Underground Fuel Storage Facility

| Red Hill | |

|---|---|

Maintenance on an empty fuel tank. | |

| Official name | Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility |

| Location | Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Purpose | Store fuel for use at Joint Base Pearl Harbor Hickam to refuel ships, aircraft, etc. |

| Status | In use |

| Construction began | 1940 |

| Opening date | 1943 |

| Construction cost | $42.2 million (1943) |

| Owner(s) | United States Government |

| Operator(s) | U.S. Navy |

|

Civil Engineering Landmark Designated in 1995 American Society of Civil Engineers | |

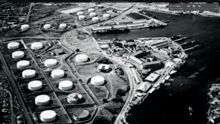

The Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility, operated by the United States Navy, supports military operations in the Pacific.[1] Unlike any other facility in the United States, Red Hill can store up to 250 million gallons of fuel. It consists of 20 steel-lined underground storage tanks (USTs) encased in concrete, and built into cavities that were mined inside of Red Hill. Each tank has a storage capacity of approximately 12.5 million gallons. The tanks are connected to three gravity-fed pipelines that run 2.5 miles inside a tunnel to fueling piers at Pearl Harbor. Each of the 20 tanks at Red Hill measures 100 feet in diameter and is 250 feet in height.[2]

Red Hill is located under a volcanic mountain ridge near Honolulu, Hawaii and was declared a Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1995.

History

As world tensions increased during the early stages of World War II, concern about the vulnerability of the many above-ground fuel storage tanks at Pearl Harbor grew. In 1940 the decision was made to build a new facility that would store more fuel and in a location that would not be exposed to an enemy attack—underground.

Construction

The site would provide unprecedented flow rates due to its elevation. In addition, the site's unique geological characteristics, including basalt rock, could support such large tanks. Federal, local government and contracted engineers and geologists performed many surveys of the Koolau Range and eventually reached a consensus on Red Hill as the best choice because it is mostly homogeneous basalt.Their original plan was to build four large under-ground tanks. These would be horizontal, as all underground tanks were at the time. However, during the planning process, the engineers decided to build the tanks vertically because construction and excavation could occur simultaneously. This was possible because a vertical shaft drilled through the centerline of the tank would allow excavated rock to funnel down onto a series of conveyor belts in the lower access tunnel.

Planners and engineers began the process by acquiring the real estate, staging equipment and materials, and building a work camp for the 3,900 people who would end up working 24/7 to complete the project. Construction started by excavating the vertical shafts for all 20 tanks concurrently with mining of the upper access and lower access tunnels. The tunnels were aligned directly in the middle of the parallel rows of shafts. Once perpendicular to the shafts, cross tunnels were mined to connect the shafts to the main access tunnels. For constructability and safety reasons (cave-ins), the upper domes needed to be built first, so the miners excavated individual ring tunnels around the circumference of each of the future upper dome bases. They then scoped out the area of the domes and proceeded to construct the steel framing, steel liner and rebar. Workers continuously poured concrete that ranged in thickness from two feet at the crown to eight feet at the base. Once the concrete cured, it was pre-stressed by pressure grouting the area between the concrete and the basalt.

Upon completion of the excavation, workers erected a steel tower in the center to the full height of 250 feet. The tower served to support concrete chutes, pipes, booms, and other equipment necessary to install the piping, concrete, and steel linings. Workers then began to erect the steel liner and rebar incrementally so that they could pour concrete in stages. Concrete was poured continually and workers had to remove wooden shoring as concrete filled. They injected pressurized grout to pre-stress the concrete by filling void space between the concrete and the gunite. When finished, the tanks were tested by slowly filling them with water while laborers in boats physically checked the entire surface area of the steel liner.

The Department of Defense has spent more than $200 million on continual technological modernization and environmental testing at Red Hill since 2006. The facility monitors the fuel level in each tank to one sixteenth of an inch and controls the movement of fuel throughout the facility. If a tank level decreases by as little as half an inch, alarms will sound in Red Hill's control room, which is continuously staffed.[3]

Environmental Impact

Groundwater Protection Plan (GPP)

Many entities, including the U.S. Navy, University of Hawaii, and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), study the movement of groundwater in and around Red Hill. Navy modeling to date indicates any fuel constituents in the groundwater are “not likely” to reach any of Oahu's drinking water sources.

Timeline of actions taken by the U.S. Navy:

- 2005: Quarterly groundwater monitoring and sampling at the Red Hill Facility.

- 2007: Environmental investigation to collect additional data for groundwater and contaminant fate (how and where it disperses) and transport modeling in order to provide better understanding and forecasting of potential impacts; contingency plan to protect drinking water well located closest to Red Hill.

- 2008: The Groundwater Protection Plan (GPP) (subsequently updated in 2009 and 2014) to mitigate risk associated with inadvertent fuel releases from the tanks.

The GPP included the follow provisions:

- A tank inspection and maintenance program

- A soil vapor monitoring program to support primary leak detection processes

- A groundwater sampling and risk assessment reporting program

- A long-term groundwater monitoring program that provides warning of potential risk to human health

- Responsibilities and response actions that will be performed should groundwater data exceed Hawaii Department of Health (DOH) environmental action levels.

- Periodic market surveys to evaluate best available leak detection technologies for large, field-constructed fuel storage facilities.[3]

Fuel Spills

In December 2013, contractors completed a three-year, scheduled, routine maintenance upgrade on tank 5 at Red Hill. This work included cleaning, inspecting, and repairing any anomalies found in the tank. At the conclusion of the overhaul in January 2014, the Navy initiated a Return to Service (RTS) evolution, refilling the tank with jet fuel (JP-8). During the RTS, the inventory management alarms sounded. Red Hill operators first assumed the alarm system was malfunctioning or producing false positives because the tank was recently overhauled and should not have been leaking. Eventually, the U.S. Navy determined the alarms were not false and reported a 27,000 gallon jet fuel loss to Hawaii DOH and the EPA.

Subsequent analysis indicated that the leak was the result of faulty work and poor quality control by the Navy's contractor, compounded by a lack of quality assurance oversight by the Navy, as well as operator error. As a consequence, the Navy, in accordance with the Administrative Order on Consent, significantly improved the tank inspection, repair, and maintenance (TIRM) processes in their TIRM report submitted on October 11, 2016.

Regarding the 27,000 gallons of fuel, the Navy's first concern was the possibility of fuel entering the drinking water supply. The nearest drinking water shaft (operated by the Navy) is 3,000 feet away and is one source that provides water to the military families at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. The next closest drinking water shaft, Halawa shaft, which is located approximately one mile away, provides drinking water to the city of Honolulu. While all test results for contamination at the Navy drinking water shaft have come back well within safe drinking water standards and results from the Halawa shaft have shown no jet fuel related contaminants, the Navy, EPA, and Hawaii DOH conducted studies to evaluate groundwater conditions and any potential impacts to groundwater resources in the area. Results taken in and around Tank 5 indicated a spike in levels of hydrocarbons in soil vapor and groundwater. Drinking water monitoring results confirmed compliance with federal and state safety standards for drinking water both before and after the January 2014 release.[4]

Following the tank 5 release in 2014, the Navy increased the testing frequency for drinking water and groundwater wells. The Navy now sends drinking water samples every quarter to certified independent laboratories that use EPA methods to analyze for contamination.

The newest groundwater monitoring well is near completion and is scheduled to come on line by the end of April 2017. Commander Navy Region Hawaii and Naval Surface Group Middle Pacific, Admiral Fuller noted, "there are have been detects of trace amounts of fuel constituents near the Navy drinking water shaft." This is in the groundwater, not the drinking water. "We're talking 17 parts per billion, as opposed to zero. The misperception is that there's a spike, but the numbers were small enough that the testing facility had to estimate the amount because the numbers were so low. The 17 parts per billion is below the threshold of something we should be concerned about, which is 100 parts per billion."

Administrative Order on Consent

The Administrative Order on Consent (AOC) is a binding legal agreement administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The AOC mandates the corrective actions to be taken in the wake of an environmental violation. Representatives from the EPA, Hawaii DOH, U.S. Navy, and Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) signed the AOC for Red Hill in September 2015. It acknowledges the shared responsibility to protect Oahu's drinking water supply and maintain Red Hill as a strategically vital resource.

The EPA and Hawaii DOH negotiated the AOC with the U.S. Navy and the DLA in response to the January 2014 fuel release from the facility. The Order requires the Navy and DLA to take actions, subject to DOH and EPA approval, to address fuel releases and implement infrastructure improvements to protect human health and the environment.The AOC requires the Navy to evaluate and improve procedures and practices to maintain the integrity of the tanks, evaluate and implement structural upgrades to the tanks, and to use the best technology available to detect leaks. The AOC also requires the Navy to determine the overall risk the facility poses to the surrounding environment.

The document includes a Statement of Work (SOW) prescribing actions the U.S. Navy must take, along with deadlines for completing each task. The SOW has eight sections:

- Overall project maintenance guidance

- Tank inspection, repair, and maintenance

- Potential tank upgrade review procedures

- Leak detection and testing

- Current and future corrosion and metal fatigue

- Investigating and remediating past fuel releases

- Development of future groundwater protection and evaluation

- Risk and vulnerability assessment of Red Hill

Hawaii DOH hosted a second meeting to address the SOW in May 2016. Participants included the DLA, DOH, and EPA as well as subject matter experts from the University of Hawaii, the Honolulu Board of Water Supply (BWS) and their consultants, State Department of Land and Natural Resources, and USGS. The EPA and DOH hired a team of world renowned subject matter experts to assess the entire Red Hill facility and went on record to say that all aspects—to include infrastructure, security measures, and operation practices—currently meet or exceed industry standards.

Follow on Investigation and Remediation

The Administrative Order on Consent (AOC) requires the Navy to develop a plan addressing the January 2014 fuel release from Tank #5 as well as plans to address any future releases of fuel. The Navy will evaluate various investigative techniques to determine which are most suitable for determining the extent of contamination in the ground around Red Hill. Each technique will be evaluated in terms of feasibility of implementation and effectiveness in detecting light non-aqueous phase liquid (LNAPL), which refers to fuel floating on top of the groundwater. The Navy will also investigate a number of remediation methods for use in the Red Hill area. The Navy will evaluate methods based on their feasibility of implementation, suitableness for use in fractured basalt geology, and effectiveness in reducing contamination.

In May 2016 the Navy submitted a scope of work to address the investigation and remediation of contamination, modeling and the groundwater monitoring network. On September 15, 2016 the Regulatory Agencies disapproved this scope of work and requested that the Navy revise the document (review and disapproval letter is available in the Additional Documents page, see link above). The Navy submitted a revised scope of work on November 5, 2016 which was conditionally approved by the Regulatory Agencies on December 2, 2016 subject to changes as detailed in the conditional approval letter (letter is available for viewing below). On January 5, 2017, the Navy submitted a new version of the Section 6 & 7 Scope of Work, available below, that addressed all of the issues noted in the Conditional Approval letter.[5]

Controversy

Public Concern

The Honolulu Civil Beat reported that even though Navy and state health officials have known about the groundwater contamination since the late 1990s — and generated thousands of pages of reports on the topic — officials from Honolulu's Board of Water Supply say they were never informed about the problems until after this most recent spill. The BWS is responsible for purveying the county's drinking water.

"I'm very concerned about the situation," said Ernest Lau, manager and chief engineer for the BWS. He stressed that the nearby aquifers are critical to Oahu's drinking water supply.[6]

The Environmental Protection Agency says millions of gallons of fuel stored in a military facility under Red Hill is unlikely to reach the water supply. "It's very unlikely that that contamination, that mass we're seeing under the tanks, gets anywhere near the Board of Water Supply wells," Steven Linder, of the EPA, told the state Health Department's Underground Fuel Tank Advisory Committee on Thursday.[7]

The Sierra Club of Hawaii launched a "Fix it up or shut it down" petition and has also demanded Hawaiʻi Department of Health, EPA, and U.S. Navy:

- Install sufficient "sentinel" monitoring wells to guard public drinking water sources from possible contamination currently in the aquifer,

- Locate the fuel that has already leaked from the storage facility and clean it up,

- Install genuine leak prevention systems, not only leak detection systems, that will guarantee there will be no future leaks from this facility.[8]

SB 1259

Senate Bill 1259 titled RELATING TO UNDERGROUND STORAGE TANKS requires, on or before 9/1/2018, that the Department of Health adopt rules for underground storage tanks and tank systems to conform to certain federal regulations and that include additional requirements for field-constructed underground storage tanks and tank systems. (SD1) The bill was introduced on January 25, 2017 and was eventually tabled.[9]

References

- ↑ JBPHH (2016-11-04), Red Hill Enabling America's Forces, retrieved 2017-04-13

- ↑ 09, US EPA,REG. "What is the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility?". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- 1 2 "Currents Magazine" (PDF).

- ↑ 09, US EPA,REG. "About the 2014 Fuel Release". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ 09, US EPA,REG. "Investigation and Remediation of Releases". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ "Red Hill: EPA May Force New Fuel Leak Detection System for Toxic Spills". Honolulu Civil Beat. 2014-01-30. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ Mendoza, Jim. "EPA: Fuel from Red Hill leak probably won't reach drinking water". Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ↑ "Red Hill Water Security". Sierra Club of Hawaiʻi. 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ "Measure Status". capitol.hawaii.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-31.