Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities

| Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities Municipios Autónomos Rebeldes Zapatistas (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Flag

Charge

| |

|

Anthem: Himno Zapatista | |

Fully or partially controlled territory by the Zapatistas in Chiapas | |

| Status | De facto autonomous region of Chiapas |

| Capital |

None (de jure) Oventik (Tiamnal, Larráinzar) (de facto)[1] 16°55′33″N 92°45′37″W / 16.92583°N 92.76028°W |

| Constitutional languages | |

| Government | Anti-capitalist confederated non-partisan consensus democracy[2] |

• Head of government | None |

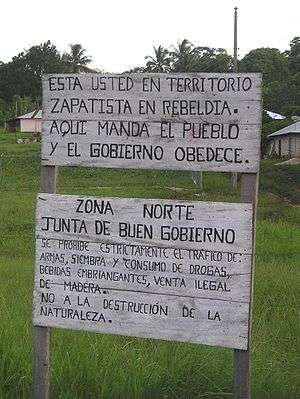

• Local leadership | Councils of Good Government |

| Autonomous region | |

| 1 January 1994 | |

• Caracoles established[3] | 9 August 2003 |

• Current Declaration of the Selva Lacandona[4] | 30 June 2005 |

| Area | |

• Total | 24,403 km2 (9,422 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 363,583[5][6] |

| Currency | Peso (MXN) |

Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (in Spanish, known as Municipios Autónomos Rebeldes Zapatistas, or by the acronym MAREZ) are territories controlled by the Neo-zapatista support bases in the Mexican state of Chiapas, founded in December 1994.

The Zapatista army, or EZLN, does not hold any power in the autonomous municipalities. According to its constitution, no commander or member of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee may take positions of authority or government in these spaces.[7]

These places are found within the official municipalities, and several are even within the same municipality, as in the case of San Andres Larrainzar and Ocosingo. The MAREZ are coordinated by Autonomous Councils and their main objectives have been to promote education and health in their territories. They also fight for land rights, labor and trade, housing, and fuel-supply issues, promoting arts (especially, indigenous language and traditions), and administering justice.[8]

Background

On 1 January 1994, thousands of EZLN members occupied towns and cities in Chiapas, burning down police stations, occupying government buildings and skirmishing with the Mexican army. The EZLN demanded “work, land, housing, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace." in their communities.[9] The Zapatistas seized over million acres from large landowners during their revolution.[10]

Distribution

Since 2003 the MAREZ coordinate in very small groups called caracoles (Spanish: "snails"). Before that, the Neo-Zapastistas used the title of Aguascalientes after the site of the EZLN-organized National Democratic Convention on 8 August 1994[11]; this name gave the allusion to the Convention of Aguascalientes during the Mexican Revolution where Emiliano Zapata and other warlords met in 1914 and Zapata made an alliance with Francisco Villa.

| MAREZ | Caracol | Former Name (Aguascalientes) | Indigenous Groups | Area and municipalities in which they are found | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mother of the sea snails of our dreams | La Realidad | tojolabales, tzeltales, and mames | Selva Fronteriza. "Ocosingo, Marques de Comillas" | |

|

Whirlwind of our words | Morelia | tzeltales, tzotziles, and tojolabales | Tzots Choj Altamirano, Comitán | |

|

Resistance toward a new dawn | La Garrucha | tzeltales | Selva Tzeltal "Ocosingo, Altamirano" | |

|

That speaks for all | Roberto Barrios | choles, zoques, and tzeltales | Zona Norte de Chiapas San Andrés Larrainzar, El Bosque, Simojovel de allende | |

|

Resistance and rebellion for humanity | Oventic | tzotziles, and tzeltales | Altos de Chiapas, San Andrés Larrainzar, Teopisca. | |

| [12] | |||||

Government

The Zapatista government is a confederation of participatory democracies similar to the ideals of libertarian socialism and left-anarchism.

At a local level, people attend a general assembly of around 300 families where anyone over the age of 12 can participate in decision-making, these assemblies strive to reach a consensus but are willing to fall back to a majority vote. Each community has 3 main administrative structures: (1) the commissariat, in charge of day-to day administration; (2) the council for land control, which deals with forestry and disputes with neighboring communities; and (3) the agencia, a community police agency.[13]

The communities form a federation with other communities to create an autonomous municipalities, which form further federations with other municipalities to create a region. The Zapatistas are composed of five regions, in total having a population of around 300,000 people.[14][15]

Economy

The Zapatista economy is similar to the libertarian socialist economic theories of mutualism and collectivist anarchism. Being mainly composed of worker cooperatives, family farms and community stores with the councils of good government providing low-interest loans, free education, radio stations and health-care to communities. The economy is largely self-reliant and agricultural, producing mainly corn, beans, coffee, bananas, sugar, cattle, chickens, pigs and clothing at cooperatives.[16] The communities have abolished private (but not personal) ownership of property and instituted a system of collective ownership of land, and they sell over $44 million worth of goods to international markets each year. Given the collective ownership of land and system of participatory democracy, hunger and violence are extremely lower compared to other impoverished Mexican communities.[17]

Public Services

The Zapatistas run hundreds of schools with thousands of teachers modeled around the principles of democratic education where students and communities collectively decide on school curriculum and students aren't graded.[18]

The Zapatistas maintain a high-quality universal healthcare service which has been praised by the World Health Organization for reducing infant mortality and providing strong primary care to residents.[19] Residents of the Zapatisa communities believe their health services are better staffed, equipped and less racist towards indigenous people than most services in Chiapas. It also works with surrounding hospitals and freely takes in patients from other communities who need to use the medical facilities that only the Zapatistas have.[20] Since 1994, the Zapatistas have built 2 new hospitals and 18 health clinics in the region the increase the well-being of communities.

The Zapatista communities are claim to be firmly environmentalist and to have stopped the extraction of oil, uranium, timber and metal from the Lacandon Jungle and stopped the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers in farming.[21] Several eco-socialist and eco-anarchist authors have praised the efforts of the Zapatistas to construct an ecological society.[22] However, the Zapatistas have also been heavily criticized by both environmentalists and the indigenous Lacandon Maya for allowing and encouraging logging, farming and settlement construction in protected areas of the Lacandon Jungle.[23][24][23]

Political affiliation

The neo-Zapatistas do not proclaim adherence to a specific political ideology beyond left-wing politics. However, the functioning of the MAREZ distinguished it programmatically from the traditional left, reclaiming Zapatista- and Magonist-inspired "indigenismo" with contributions from libertarian socialism, autonomous Marxism, and anarchism.

Criticism

The Zapatistas have faced criticism from several socialists and anarchists. Anarchists have argued that the Zapatista communities have not taken enough effort to fully abolish the capitalist practices of wage labor, rent and multinational investment from their communities.[10] Whilst non-anarchist socialists have criticized them for not centralizing their power enough and exploiting their natural resources to fund social programs in their communities and sponsor revolutionary activity throughout Mexico.[25] Some eco-anarchists have criticized the communities from not engaging in a fully vegetarian lifestyle, continuing to use plastic and deforest the surrounding jungle to raise cattle.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ "Caracoles y Juntas de Buen Gobierno". Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ http://links.org.au/mexico-zapatistas-ezln-oventic

- ↑ http://www.jornada.com.mx/2003/09/26/per-texto.html

- ↑ http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2005/06/30/sixth-declaration-of-the-selva-lacandona/

- ↑ http://www.sinembargo.mx/17-03-2018/3398402

- ↑ http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/chis/poblacion/comotu.aspx?tema=me&e=07

- ↑ Gloria Muñóz Ramírez (2003). 20 y 10 el fuego y la palabra. Revista Rebeldía y Demos, Desarrollo de Medios, S.A. de C.V. La Jornada Ediciones.

- ↑ CHIAPAS: LA TRECEAVA ESTELA. Quinta parte: Una historia. Julio de 2003

- ↑ Ramírez, Gloria (2008). The Fire and the Word: A History of the Zapatista Movement. p. 22.

- 1 2 Grubacic, Andrej (2016). Living at the Edges of Capitalism: Adventures in Exile and Mutual Aid. ISBN 9780520287303.

- ↑ Utopía, CCD. "LOS AGUASCALIENTES: Centros Culturales en el Corazón de la Selva Lacandona y en las montañas y rincones zapatistas". itzcuintli.tripod.com. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ↑ Hidalgo, Onésimo and Castro Soto, Gustavo. Cambios en el EZLN. CIEPAC, 2003.

- ↑ Barmeyer, Niels (2009). Developing Zapatista Autonomy: Conflict and NGO Involvement in Rebel Chiapas. University of New Mexico Press. pp. Chapter Three: "Who is Running the Show? The Workings of Zapatista Government".

- ↑ Andrew Flood, "The Zapatistas, anarchism and 'Direct democracy'", Anarcho-Syndicalist Review 27 (Winter 1999)

- ↑ El Kilombo Intergaláctico and Subcomandante Marcos, Beyond Resistance: Everything (Durham: PaperBoat Express, 2007), 23.

- ↑ Resistencia Autónoma: Cuaderno de texto de primer grado del curso de “La Libertad según l@s Zapatistas”, 6-13.

- ↑ Esteva, Gustavo. Liberty According to the Zapatistas.

- ↑ Zibechi, Raúl (2012). Territories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social Movements. AK Press. p. 132.

- ↑ J.H. Cuevas, “Health and Autonomy: the case of Chiapas”, March 2007.

- ↑ Translated by Dan Fischer, 'Resistencia Autónoma: Cuaderno de texto de primer grado del curso de “La Libertad según l@s Zapatistas” 19.

- ↑ Gobierno Autónomo I: Cuaderno de texto de primer grado del curso de “La Libertad según l@s Zapatistas”, 19.

- ↑ Kovel, Joel (2007). Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World?. Zed Books. p. 253.

- 1 2 Mark Stevenson (Associated Press) (July 14, 2002). "Unusual battle lines form around jungle". The Miami Herald. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Inbreeding, Rebels And Tv Threaten Mexican Jungle Tribe's Existence". Chicago Tribune. February 24, 1994. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ↑ Louis Proyect, "Fetishizing the Zapatistas: a critique of "Change the World Without Taking Power", marxmail.org, 7 June 2003

- ↑ Javier Sethness Castro, "Neo-Zapatista Autonomy", Counterpunch, 23 January 2014