Pyramids of Mars

| 082 – Pyramids of Mars | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who serial | |||||

"Kneel before the might of Sutekh!" | |||||

| Cast | |||||

|

Others

| |||||

| Production | |||||

| Directed by | Paddy Russell | ||||

| Written by | "Stephen Harris" (Robert Holmes and Lewis Greifer) | ||||

| Script editor | Robert Holmes | ||||

| Produced by | Philip Hinchcliffe | ||||

| Executive producer(s) | None | ||||

| Incidental music composer | Dudley Simpson | ||||

| Production code | 4G | ||||

| Series | Season 13 | ||||

| Length | 4 episodes, 25 minutes each | ||||

| Originally broadcast | 25 October – 15 November 1975 | ||||

| Chronology | |||||

| |||||

Pyramids of Mars is the third serial of the 13th season of the British science fiction television series Doctor Who, which was first broadcast in four weekly parts on BBC1 from 25 October to 15 November 1975.

The serial is set in England and Egypt and on Mars in 1911. In the serial, the burial chamber of the alien Osiran Sutekh (Gabriel Woolf), the inspiration for the Egyptian god Set, is unearthed by the archaeology professor Marcus Scarman (Bernard Archard). Alive but immobilised, Sutekh seeks his freedom by using Professor Scarman as his servant to destroy the jewel on a pyramid on Mars which is keeping him prisoner.

Plot

In 1911 Egypt, an archaeology professor Marcus Scarman excavates a pyramid and finds the door to the burial chamber is inscribed with the Eye of Horus. His Egyptian assistants flee in fear as he entered the chamber alone and is hit by a beam of green light. The Doctor, intended to land in UNIT's base, ends up in the basement of an English estate after the TARDIS was forced out of its flight path as Sarah sees an apparition of a Typhonian Animal in the console room. The two are found by the butler, who reveals they are in the Scarman estate which has been taken over by a mysterious Egyptian named Ibrahim Namin claiming to represent Scarman's estate, Scarman's friend Dr Warlock confronting him over foul play. When Namin sends a robot dressed like an Egyptian mummy after them and Warlock, they reach a hunting lodge used by Scarman's brother Laurence, whose marconiscope intercepted a signal from Mars. The Doctor decodes the signal as "Beware Sutekh", explaining to Sarah that Sutekh is the last of a powerful alien race called the Osirans, his imprisonment by his brother Horus being the inspiration for ancient Egyptian mythology.

Namin and the mummies greet the arrival of Sutekh's servant who travels to the priory via a spacetime tunnel portal disguised assarcophagus, the servant killing Namin for serving his purpose. The servant is revealed to be Marcus Scarman, whom the Doctor realizes is a corpse animated by Sutekh's will. As Scarman and the robots secure the estate's perimeter while killing off anyone they find like Warlock before constructing an Osirian war missile aimed for Mars, Doctor disrupts the tunnel using the TARDIS key before retrieving Namin's ring from his corpse. Hiding in the TARDIS, Sarah suggests they should just leave with the Doctor briefly taking them to 1980 to show what becomes of Earth if they allow Sutekh to escape.

Once back in 1911, the Doctor makes a jamming unit with Namin's ring to break Sutekh's hold over those animated by his will including Scarman, causing Laurence to attempt stopping him from activating the device. The robots chasing after the groundskeeper Clements kill him before they overrun the hunting lodge, one shutting down after destroying the machine while Sarah uses Namin's ring to send the other back to Scarman. The Doctor decides to blow up the partially assembled rocket, Laurence suggesting the blasting gelignite kept in Clements's hut. The Doctor and Sarah leave to obtain the gelignite, ordering Laurence to strip the bindings from the deactivated robot. When Scarman arrives, Laurence attempts to rekindle his brother's humanity and ends up being killed. After he and Sarah return, the Doctor disguises himself under the robot's binding to set up the explosives before he and Sarah detonate them. But Sutekh telekinetically suppresses the explosion, forcing the Doctor to use space-time tunnel to reach Sutekh and break his concentration for the explosion to run its course. A furious Sutekh interrogates the Doctor before decides to turn him into a thrall to transport Scarman to a Martian pyramid to destroy the Eye of Horus which maintains his prison.

Though strangled once serving his purpose, the Doctor survived through his respiratory bypass system as he and Sarah follow Scarman through a series of locked chambers which are dependent upon solving logical and philosophical puzzles. While the Doctor is unable to stop Scarman from destroying the Eye, Scarman decaying to dust, he realizes that Sutekh would not be released for two minutes due to the time of the Eye's signal traveling from Mars to Earth. The Doctor returns to the Priory and use a module from the TARDIS on Sutekh as he was traveling the space-time tunnel, subjecting the Osirian to rapid aging until his body dissolves once aged passed 11,000 years. But the Doctor's action causes the portal to overload with him and Sarah fleeing into the TARDIS as the priory is consumed in flames.

Continuity

Sarah wears a dress which the Doctor says belonged to Victoria.[1] She remarks that the puzzles are similar to those in the Exxilon City in Death to the Daleks (1974), although she personally never entered the City.[1]

Production

The story as originally written by Lewis Greifer was considered unworkable. As Greifer was unavailable to perform rewrites, the scripts were completely rewritten by Robert Holmes. The pseudonym used on transmission was Stephen Harris. Pyramids of Mars contributes to the UNIT dating controversy, one of the contradictions in the Doctor Who universe.

The exterior scenes were shot on the Stargroves estate in Hampshire, a Victorian mansion noted for its ornate, Gothic revival style of architecture[2] which was owned by Mick Jagger at the time. The same location would be used during the filming of Image of the Fendahl (1977). The new TARDIS console, which debuted in the preceding story Planet of Evil, does not appear again until The Invisible Enemy (1977). Owing to the cost of setting up the TARDIS console room for the filming of only a handful of scenes, a new console set was designed for the following season. Tom Baker and Elisabeth Sladen improvised a number of moments in this story, most notably a scene in Part Four where the Doctor and Sarah start to walk out of their hiding place and then when they see a mummy, quickly dart back into it. Baker based the scene on a Marx Brothers routine.

Several scenes were deleted from the final broadcast. A model shot of the TARDIS landing in the landscape of a barren, alternative 1980 Earth was to be used in Part Two, but director Paddy Russell decided viewers would feel more impact if the first scene of the new Earth was Sarah's reaction as the TARDIS doors opened. Three scenes of effects such as doors opening and the Doctor materializing from the sarcophagus were removed from the final edit of Part Four because Russell felt the mixes were not good enough. These scenes were included on the DVD, along with an alternate version of the poacher being hunted down in Part Two, and a full version of the Osiran rocket explosion.

Although the name of Sutekh's race is pronounced "Osiran" throughout the serial, the scripts and publicity material spell it as "Osirian" in some places and as "Osiran" in others.[3]

Cast notes

Features a guest appearance by Michael Sheard; he was cast by director Paddy Russell without any audition, purely on the recommendation of production assistant Peter Grimwade. Sheard previously featured in The Ark (1966) and The Mind of Evil (1971) and would later appear in The Invisible Enemy (1977), Castrovalva (1982) and Remembrance of the Daleks (1988). Bernard Archard previously played Bragen in The Power of the Daleks (1966). Michael Bilton previously played Teligny in The Massacre of St Bartholomew's Eve (1966). George Tovey was the father of Roberta Tovey, who appeared as Susan in the films Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965) and Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966).

Gabriel Woolf reprised his role as Sutekh in the Faction Paradox audio dramas Coming to Dust (2005), The Ship of a Billion Years (2006), Body Politic (2008), Words from Nine Divinities (2008), Ozymandias (2009) and The Judgment of Sutekh (2009), from Magic Bullet Productions and in The New Adventures of Bernice Summerfield: The Judgement of Sutekh for Big Finish Productions. He also provided the voice of Sutekh for the comedy sketch Oh Mummy: Sutekh's Story, included on the DVD release of Pyramids of Mars. Woolf would go on to provide the voice of The Beast in the 2006 episodes "The Impossible Planet" and "The Satan Pit". He also provided the voice of Governor Rossitor in the Big Finish audio plays Arrangements for War and Thicker than Water.

Broadcast and reception

| Episode | Title | Run time | Original air date | UK viewers (millions) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Part One" | 25:22 | 25 October 1975 | 10.5 |

| 2 | "Part Two" | 23:53 | 1 November 1975 | 11.3 |

| 3 | "Part Three" | 24:32 | 8 November 1975 | 9.4 |

| 4 | "Part Four" | 24:52 | 15 November 1975 | 11.7 |

The story was edited and condensed into a single, one-hour omnibus episode, broadcast on BBC1 at 5:50 pm on 27 November 1976,[5] reaching 13.7 million viewers,[6] the highest audience achieved by Doctor Who in its entire history to date. The figure was not bettered until the broadcast of City of Death in 1979. BBC2 broadcast the four episodes on consecutive Sundays from 6–27 March 1994 at noon, reaching 1.1, 1.1, 0.9 & 1.0 million viewers respectively.[7]

Paul Cornell, Martin Day, and Keith Topping gave the serial a positive review in The Discontinuity Guide (1995), praising the "chilling" adversary and some of the conversations.[1] In The Television Companion (1998), David J. Howe and Stephen James Walker described the first episode as "an excellent scene-setter" and the story as "near-flawless". They wrote that Pyramids of Mars gave the "fullest expression" of the Gothic horror era and had high production values and a good guest cast.[3] In 2010, Patrick Mulkern of Radio Times called it "a bona fide classic" with "arguably the most polished production to date", and praised the powerful plot. However, he disliked how UNIT was dismissed in the season, and found "minor, amusing quibbles" with the plot.[8] Charlie Jane Anders of io9 described Pyramids of Mars as "just a lovely, solid adventure story", highlighting the way the Doctor seemed outmatched, the pace, and Sarah Jane.[9] In a 2010 article, Anders also listed the cliffhanger to the third episode — in which the Doctor is forced to confront Sutekh — as one of the greatest Doctor Who cliffhangers ever.[10] In a 2014 Doctor Who Magazine poll to determine the best Doctor Who stories of all time, readers voted Pyramids of Mars to eighth place.[11]

The writer John Kenneth Muir was critical of the serial, querying the Egyptian mythology conceit that is woven through the whole story; he questioned a number of apparently illogical story elements, such as why the robots that guard the priory were disguised as Egyptian mummies, and why the Osiran rocket was shaped as a pyramid. In his assessment, the use of ancient Egyptian objects and symbols by the Osiran race was inadequately explained in the script, and he contrasted the Pyramids of Mars unfavourably with Stargate, a 1994 television series which relied heavily on the concept of ancient astronauts visiting Earth. Muir traced parallels with earlier Doctor Who serials such as The Dæmons (1971) and Terror of the Zygons (1975) which had also drawn on the idea of ancient Earth mythologies having extraterrestrial origins. Like The Dæmons and Tomb of the Cybermen (1967), Pyramids of Mars exploited many familiar conventions of classic mummy films, but less successfully in Muir's view.[12]

John J Johnston, vice-chair of the Egypt Exploration Society, explored the influences on the Pyramids of Mars in the Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture. He argued that the story drew heavily on a number of classic horror films such as Boris Karloff's The Mummy (1932) and Hammer Films' The Mummy (1959), in its setting and the performance of the actors. Johnston also noted the influences of archaeology on the production design. According to Johnston, the robot mummies designed by the BBC's Barbara Kidd were inspired by an ancient rock painting of a mysterious domed-headed figure that had been discovered by Henri Lhote in the Sahara Desert in the 1950s, and which Lhote had nicknamed "the Great Martian God". Similarly, he considered Sutekh's mask to have been modelled on a statue of a bearded man dating from c.3500 BCE that had been excavated at Gebelein by Louis Lortet in 1908.[13]

Commercial releases

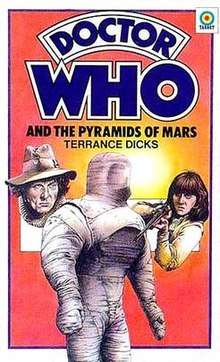

In print

| |

| Author | Terrance Dicks |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Chris Achilleos |

| Series |

Doctor Who book: Target novelisations |

Release number | 50 |

| Publisher | Target Books |

Publication date | 16 December 1976 |

| ISBN | 0-426-11666-6 |

A novelisation of this serial, written by Terrance Dicks, was published by Target Books in December 1976. The novelisation contains a substantial prologue giving the history of Sutekh and the Osirans and features an epilogue in which a future Sarah researches the destruction of the Priory and how it was explained. An unabridged reading of the novelisation by actor Tom Baker was released on CD in August 2008 by BBC Audiobooks.

Home media

The story first came out on VHS and Betamax in an omnibus format in February 1985. It was subsequently released in episodic format in April 1994. It was released on DVD in the United Kingdom on 1 March 2004. It was also released on 31 October 2011 as an extra on The Sarah Jane Adventures Series 4 DVD and Blu-ray boxset as a tribute to Elisabeth Sladen who had died earlier in the year.[14]

In 2013 it was released on DVD again as part of the "Doctor Who: The Doctors Revisited 1–4" box set, alongside The Aztecs, Tomb of the Cybermen and Spearhead from Space. Alongside a documentary on the Fourth Doctor, the disc features the serial put together as a single feature in widescreen format with an introduction from current show runner Steven Moffat, as well as its original version.

References

- 1 2 3 Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). "Pyramids of Mars". The Discontinuity Guide. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-426-20442-5.

- ↑ Historic England. "Stargrove (1339802)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- 1 2 Howe, David J & Walker, Stephen James (2003). The Television Companion: The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to DOCTOR WHO (2nd ed.). Surrey, UK: Telos Publishing Ltd. p. 387. ISBN 1-903889-51-0.

- ↑ "Ratings Guide". Doctor Who News. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ↑ "Dr Who: Pyramids of Mars". 25 November 1976. p. 19 – via BBC Genome.

- ↑ doctorwhonews.net. "Doctor Who Guide: broadcasting for Pyramids of Mars".

- ↑ doctorwhonews.net. "Doctor Who Guide: broadcasting for Pyramids of Mars".

- ↑ Mulkern, Patrick (14 July 2010). "Doctor Who: Pyramids of Mars". Radio Times. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Anders, Charlie Jane (30 August 2012). "Old-School Doctor Who Episodes That Everyone Should Watch". io9. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Anders, Charlie Jane (31 August 2010). "Greatest Doctor Who Cliffhangers Of All Time!". io9. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Top 10 Doctor Who stories of all time". Doctor Who Magazine. June 21, 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (2007). "Season 13". A Critical History of Doctor Who on Television. McFarland. pp. 237–241. ISBN 9781476604541.

- ↑ Johnston, John J (2014). "Doctor Who: Pyramids of Mars". In Cardin, Matt. Mummies around the World: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610694209. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ↑ Martin, Will (20 September 2011). "The Sarah Jane Adventures: Series 4 DVD artwork revealed". Cult Box. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fourth Doctor |

- Pyramids of Mars at BBC Online

- Pyramids of Mars at Doctor Who: A Brief History of Time (Travel)

- Pyramids of Mars at the Doctor Who Reference Guide

Reviews

- Pyramids of Mars reviews at Outpost Gallifrey

- Pyramids of Mars reviews at The Doctor Who Ratings Guide