Pre-exposure prophylaxis

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of drugs to prevent disease in people who have not yet been exposed to the disease-causing agent. The term typically refers to the use of antiviral drugs as a strategy for the prevention of HIV/AIDS.

PrEP is one of a number of HIV prevention strategies for people who are HIV negative but who also have higher-than-average risk of contracting HIV, including sexually active adults at increased risk of HIV (e.g. men who have sex with men), people who engage in injection drug use (see drug injection), and serodiscordant sexually active couples.[1]

The only drug that any health organization recommends for HIV/AIDS PrEP is Truvada, which is the brand name of the Gilead Sciences drug combination of tenofovir/emtricitabine. Patients on PrEP take Truvada every day and must also agree to see their healthcare provider at least every three months for follow-up testing.[1] When used as directed, PrEP has been shown to be highly effective, reducing the risk of contracting HIV by 92%.[2][3] PrEP is intended for use along with other risk reduction strategies such as condoms because people taking PrEP are still at some risk of contracting HIV, especially those who do not take PrEP consistently, and because people on PrEP remain at risk for other types of sexually transmitted infection.[4]

Clinical use

In the United States, federal guidelines recommend the use of PrEP for HIV-negative adults with the following characteristics:

- sexually active in the last 6 months and NOT in a sexually monogamous relationship with a recently tested HIV-negative partner, and who...[1]

- is a man who has sex with men, and who...

- has had anal sex with another man in the past 6 months without a condom, or...

- has had a sexually transmitted infection in the past 6 months

- or is a sexually active adult (male or female with male or female partners), and who...

- is a man who has sex with both men and women, or...

- has sex with partners at increased risk of having HIV (e.g. injection drug users, men who have sex with men) without consistent condom use

- is a man who has sex with men, and who...

- or anyone who has injected illicit drugs in the past six months, shared recreational drug injection equipment with other drug users in the past six months, or who has been in treatment for injection drug use in the past six months

Other government health agencies from around the world have devised their own national guidelines for how to use PrEP to prevent HIV infection in those at high risk, including Botswana, Canada, Kenya, Lesotho, South Africa, Uganda, the United Kingdom, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.[5]

Often, lab testing is required before starting PrEP, including a test for HIV. Once PrEP is initiated, patients are asked to see their provider at least every three to six months. During those visits, healthcare providers may want to repeat testing for HIV, test for other sexually transmitted infections, monitor kidney function, and/or test for pregnancy.[1]

PrEP has been shown to be effective at reducing the risk of contracting HIV in individuals at increased risk.[1] However, PrEP is not 100% effective at preventing HIV, even in people who take the medication as prescribed. There have been several reported cases of people who despite taking PrEP became infected with HIV.[6] People taking PrEP are recommended to use other risk reducing strategies along with PrEP, like condoms.[1] If someone on PrEP contracts HIV, they may experience the Signs and symptoms of HIV/AIDS.[7]

Side effects

Research has shown that PrEP is generally safe and well tolerated for most patients, although some side effects have been noted to occur. Some patients experience a "start-up syndrome" involving nausea, headache, and/or stomach issues, which generally resolve within a few weeks of starting the PrEP medication.[1][8] Research has shown that the use of Truvada as PrEP has been associated with mild declines in kidney function. These declines were mild, stabilized after several weeks of being on the drug, and reversed once the drug was discontinued.[9][10]

Fat redistribution and accumulation has been observed in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy, particularly older antiretrovirals,[11] including fat reductions in the face, limbs, and buttocks and increases in visceral fat of the abdomen and accumulations in the upper back.[12] Research and study outcome analysis suggests that emtricitabine/tenofovir does not have a significant effect on fat redistribution or accumulation when used as pre-exposure prophylaxis in HIV negative individuals.[13] As of early 2018 these studies have not assessed in detail subtle changes in fat distribution that may be possible with the drug when used as PrEP, and statistically significant - though transient - weight changes have been attributed to detectible drug concentrations in the body.[14] Anecdotal evidence does not currently suggest significant reductions in facial or gluteal region adipose tissue and among PrEP users; the drug does not have a "reputation" as a cause of fat changes.

Access and adoption

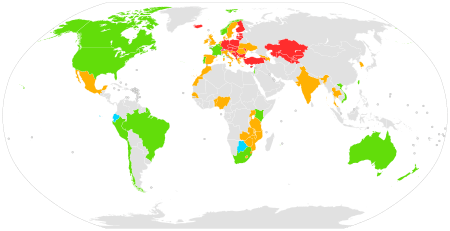

|

Approved

Approved for off-label use

Ongoing and planned demonstration projects

Completed demonstration projects

No planned demonstration project

No data

In the United Kingdom, Scotland was the only nation to approve the use of PrEP |

Approval for use

Truvada was previously only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat HIV in those already infected. In 2012, the FDA approved the drug for use as PrEP, based on growing evidence that the drug was safe and effective at preventing HIV in populations at increased risk of infection.[15]

In 2012, the World Health Organization issued guidelines for PrEP and made similar recommendations for its use among men and transgender women who have sex with men. The WHO noted that "international scientific consensus is emerging that antiretroviral drugs, including PrEP, significantly reduce the risk of sexual acquisition and transmission of HIV regardless of population or setting."[16]:8,10,11 In 2014, on the basis of further evidence, the WHO updated the recommendation for men who have sex with men to state that PrEP "is recommended as an additional HIV prevention choice within a comprehensive HIV prevention package."[17]:4 In November 2015 the WHO expanded this further, on the basis of further evidence, and stated that it had "broadened the recommendation to include all population groups at substantial risk of HIV infection" and emphasized that PrEP should be "an additional prevention choice in a comprehensive package of services."[18]

As of 2018, numerous countries have now approved the use of PrEP for HIV/AIDS prevention, including the United States, South Korea,[19] France, Norway,[20] Australia,[21] Israel,[22] Canada,[22] Kenya, South Africa, Peru, Thailand, the European Union[23][24] and Taiwan.[25]

New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to publicly fund PrEP for the prevention of HIV from 1 March 2018. Funded access to PrEP will require that people undergo regular testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, and are monitored for risk of side effects. People taking funded PrEP will receive advice on ways to reduce the risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections.[26]

In Australia, the country's Therapeutic Goods Administration approved the use of Truvada as PrEP in May 2016, allowing Australian providers to legally prescribe the medication. In February 2018, Australia's Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee recommended including Truvada as PrEP on the country's Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), slashing the cost of access to the drug from $10,000 to under $500 a year.[27] The drug begins being listed on the PBS from 1 April 2018.[28]

Availability and pricing

In the United States, PrEP is available only by prescription. Patients interested in learning more about PrEP can contact their healthcare providers.[1] Emory University hosts a search engine to help US patients with or without insurance find healthcare providers who can prescribe PrEP.[29]

PrEP drugs can also be expensive, with tremendous variation in cost across different countries. In the US, a prescription for PrEP can cost $8,000-$14,000/year.[30] In the UK, a prescription for PrEP can cost about £4,200/year[31] Some health organizations, including the U.K.'s NHS,[32] have challenged the funding of PrEP out of concern for the cost.

Multiple programs exist to help make PrEP more accessible to those who might benefit from the drug. In 2015, the US CDC published guidelines to help American patients figure out how to pay for PrEP. Those with health insurance can find out from their health insurer whether PrEP and the associated costs (e.g. visits to the doctor, lab tests) would be covered.[33] Those without health insurance or for whom health insurance has declined to pay for PrEP may be eligible for free PrEP from the drug's manufacturer, Gilead.[34] A similar program exists to reduce or eliminate the cost of the copayment for PrEP among insured patients, also sponsored by Gilead.[35] Others turn to online pharmacies to access cheaper generic versions of PrEP.[36] For instance, a dramatic decline in new HIV infections in London, UK in 2016 has been attributed by some to access to PrEP through online pharmacies, although others have expressed concerns about the safety and reliability of accessing PrEP through such online pharmacies.[37][36][38]

Despite these programs, there are significant disparities between PrEP access and uptake in high-risk populations. Patients that are currently accessing PrEP services are not the ones from population in which HIV impacts the most. According to a press release in March of 2018 from researchers at the CDC, although two-thirds of individuals who could potentially benefit from PrEP are African-American or Latino, they account for the smallest percentage of PrEP prescriptions.[39] The number of PrEP users in the Northeast region of the U.S. were found to be around twice that of those living in the West, South, or Midwest. Factors that contribute to lack of access are often intersectional, with challenges due to poverty, racism, homophobia, stigma and physician-patient barriers. African-American women and men, especially in the Southern U.S., are observed to have more limited uptake of PrEP at disproportionate rates, despite over half of new HIV diagnoses occurring there. [40][41]

Politics and culture

Since the FDA approval of PrEP for the prevention of HIV, moves toward greater adoption of PrEP have been met with controversy, especially around the overall public health effect of widespread adoption, the cost of PrEP and associated disparities in availability and access. Many public health organizations and governments have embraced PrEP as a part of their overall strategy for reducing HIV. For example, in 2014 New York state governor Andrew Cuomo initiated a three-part plan to reduce HIV across New York that specifically emphasized access to PrEP.[42] Similarly, the city of San Francisco launched a "Getting to Zero" campaign. The campaign aims to dramatically reduce the number of new HIV infections in the city and relies on expanding access to PrEP as a key strategy for achieving that goal.[43] Public health officials report that since 2013 the number of new HIV infections in San Francisco has decreased almost 50% and that such improvements are likely related to the city's campaign to reduce new infections.[44] Additionally, numerous public health campaigns have been launched to educate the public about PrEP. For instance, in New York City in 2016 Gay Men's Health Crisis launched an ad campaign in bus shelters across the city reminding riders that adherence to PrEP is important to ensuring the regimen is maximally effective.[45]

Despite those efforts, PrEP remains controversial among some who worry that widespread PrEP adoption could cause public health issues by enabling risky sexual behaviors. For instance, AIDS Healthcare Foundation founder and director Michael Weinstein has been vocal in his opposition to PrEP adoption, suggesting that PrEP causes people to make riskier decisions about sex than they would otherwise make.[46] Some researchers, however, believe that there is insufficient data to determine whether or not PrEP implementation has an effect on the rate of other sexually transmitted infections.[47] Other critics point out that despite implementation of PrEP, significant disparities exist. For example, some point out that African Americans bear a disproportionate burden of HIV infections but may be less likely than whites to access PrEP.[48] Still other critics of PrEP object to the high cost of the regimen. For example, the U.K.'s NHS initially refused to offer PrEP to patients citing concerns about cost and suggested that local officials ought to bear the responsibility of paying for the drug. However, following significant advocacy efforts, the NHS has started to offer PrEP to patients in the UK in 2017.[49]

Research

Most PrEP studies use the drug tenofovir or a tenofovir/emtricitabine combination (Truvada) that is delivered orally. Initial studies of PrEP strategies in non-human primates showed a reduced risk of infection among animals that receive ARVs prior to exposure to a simian form of HIV. A 2007 study at UT-Southwestern (Dallas) and the University of Minnesota showed PrEP to be effective in "humanized" laboratory mice.[50] In 2008, the iPrEx study demonstrated 42% reduction of HIV infection among men who have sex with men,[51] and subsequent analysis of the data has suggested that 99% protection is achievable if the drugs are taken every day.[52] Below is a table summarizing some of the major research studies that demonstrated PrEP with Truvada to be effective across different populations.

PrEP approaches with agents besides oral Truvada are being investigated. There has been some evidence that other regimens, like ones based on the antiretroviral agent Maraviroc, could potentially prevent HIV infection.[53] Similarly, researchers are investigating whether drugs could be used in ways other than a daily oral pill to prevent HIV, including taking a long-acting PrEP injection, PrEP-releasing implants, or rectally administered PrEP.[54] However, it is important to keep in mind that as of 2017 major public health organizations such as the US Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization recommend only daily oral Truvada for use as PrEP.[1][18]

| Study | Type | Type of PrEP | Study Population | Efficacy | Percent of patients who took medication (adherence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPRISA 004 | Double-blind, randomized | Pericoital tenofovir gel | South African females | 39% reduction of HIV infection[55] | 72% by applicator count[56] |

| iPrEx | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir | Men who have sex with men and transgender women | 42% reduction of HIV infection.[51] 99% reduction estimated with daily adherence[52] | 54% detectable in blood[57] | |

| Partners PrEP | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir; oral tenofovir | African heterosexual couples | Reduction of infection by 73% with Truvada and 62% with tenofovir[58] | 80% with Truvada and 83% with tenofovir[59] detectable in blood | |

| TDF2 | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir | Botswana heterosexual couples | 63% reduction of infection[8] | 84% by pill count[60] | |

| FEM-PrEP | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir | African heterosexual females | No reduction (study halted due to low adherence) | <30% with detectable levels in blood[61] | |

| VOICE 003 | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir; oral tenofovir; vaginal tenofovir gel | African heterosexual females | No reduction in oral tenofovir or vaginal gel arms [oral emtricitabine/tenofovir arm ongoing][8] | <30% with detectable levels in blood[62] | |

| Bangkok Tenofovir Study | Randomised, double-blind | Oral tenofovir | Thai male injection drug users | 48.9% reduction of infection[63] | 84% by directly observed therapy and study diaries[64] |

| IPERGAY | Randomized, double-blind | Oral emtricitabine/tenofovir | French gay males | 86% reduction of infection[65][66] (video summary) | 86% with detectable levels in blood[65] |

| PROUD | Randomized, open-label | Oral tenofovir-emtricitabine | High-risk men who have sex with men in England | 86% reduction of HIV incidence[67] | |

| HPTN 083 | Randomized, double-blind | Cabotegravir versus emtricitabine/tenofovir | ongoing | ||

Increased risk-taking

While PrEP appears to be extremely successful in suppressing the spread of HIV infection, there is some evidence that the reduction in HIV risk has led to some people taking more sexual risks; specifically, reduced use of condoms in anal sex,[68] raising risks of spreading sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. In a meta-analysis of 18 studies, researchers found that rates of new diagnoses of STIs among MSM (men who have sex with men) given PrEP were 25.3 times greater for gonorrhea, 11.2 times greater for chlamydia and 44.6 times greater for syphilis, compared with the rates among MSM not given PrEP.[69]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 US Public Health Service. "PREEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS FOR THE PREVENTION OF HIV INFECTION IN THE UNITED STATES - 2014" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) | HIV Risk and Prevention | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- ↑ Jiang J, Yang X, Ye L, Zhou B, Ning C, Huang J, Liang B, Zhong X, Huang A, Tao R, Cao C, Chen H, Liang H (2014-02-03). "Pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in high risk populations: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS One. 9 (2): e87674. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087674. PMC 3912017. PMID 24498350.

- ↑ Lowder JB (February 26, 2016). "PrEP Is Not Magic—and Treating It That Way Undermines Its Incredible Power". Slate. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ↑ "National Policies and Guidelines for PrEP". PrEP Watch. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ Ryan B (16 February 2017). "PrEP Fails in a Third Man, But This Time HIV Drug Resistance Is Not to Blame". Poz.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Daar ES, Little S, Pitt J, Santangelo J, Ho P, Harawa N, Kerndt P, Glorgi JV, Bai J, Gaut P, Richman DD, Mandel S, Nichols S (January 2001). "Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Los Angeles County Primary HIV Infection Recruitment Network". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (1): 25–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00010. PMID 11187417.

- 1 2 3 Celum CL (December 2011). "HIV preexposure prophylaxis: new data and potential use". Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 19 (5): 181–5. PMID 22298887.

- ↑ Treatment News (23 February 2016). "Truvada as PrEP Against HIV Leads to Modest Decline in Kidney Function". Poz.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Carter M (18 February 2014). "PREP Truvada PrEP does not harm the kidneys, trial shows". AIDSMap.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Changes to Your Face and Body (Lipodystrophy & Wasting)". POZ. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ "US Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) label" (PDF). FDA. March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-21.

- ↑ "PrEP does not raise lipids or alter body fat, safety study finds". Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ "Truvada as HIV PrEP not associated with net fat increase". www.healio.com. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ Gilead. "U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approves Gilead's Truvada® for Reducing the Risk of Acquiring HIV". Gilead. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Guidance on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV: recommendations for use in the context of demonstration projects" (PDF). WHO. July 2012.

- ↑ "Policy brief: Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, 2014" (PDF). WHO. July 2014.

- 1 2 "WHO expands recommendation on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV infection (PrEP)" (PDF). World Health Organization. November 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "Norway becomes first country to offer free PrEP - Star Observer". starobserver.com.au. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)". AFAO.org.au. Australian Federation of AIDS Organizations. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Canada and Israel OK Truvada as PrEP to Prevent HIV". POZ. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Brooks M (22 July 2016). "Truvada Recommended as First Drug for HIV PrEP in Europe". Medscape. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "European Medicines Agency - News and Events - First medicine for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis recommended for approval in the EU". ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Gilead Sciences Policy Position. "Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention" (PDF). Gilead Sciences. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "HIV prevention drug Truvada to be publicly funded in New Zealand". Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ↑ "'HIV has nowhere to go now': Breakthrough drug PrEP to be approved for public subsidy". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ↑ "HIV drug PrEP price to be slashed, increasing chances of eliminating virus in Australia". ABC News. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Emory University. "PrEP Locator". Emory University PrEP Locator. Emory University. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ New York State Department of Public Health. "re-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Prevent HIV Infection: Questions and Answers". Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Prevent HIV Infection: Questions and Answers. New York State Department of Public Health. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "NHS watchdog to weigh cost of HIV prevention drug Prep". BBC News. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Make PrEP available". tht.org.uk. Terrence Higgins Trust. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Covering the Cost of PrEP Care" (PDF). Paying for PrEP. Centers for Disease Control, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Truvada for PrEP Medication Assistance Program". Truvada for PrEP Medication Assistance Program. Gilead Sciences. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Welcome to The Gilead Advancing Access® Co-pay Program". Copay Coupon Card. Gilead Sciences. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- 1 2 Wilson C (9 January 2017). "Massive drop in London HIV rates may be due to internet drugs". New Scientist. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Dramatic fall in London HIV 'may be due to internet drugs'". Evening Standard. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "HIV 'may soon be wiped out in London' after dramatic drop in new infections". The Independent. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "CROI PrEP Press Release". NCHHSTP | CDC. 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ (January 2017). "Brief Report: The Right People, Right Places, and Right Practices: Disparities in PrEP Access Among African American Men, Women, and MSM in the Deep South". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 74 (1): 56–59. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001165. PMC 5903558. PMID 27552156.

- ↑ "PrEP use growing in US, but not reaching all those in need". Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ New York State Department of Public Health. "Ending the AIDS Epidemic in New York State". New York State Department of Public Health. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "About HIV and San Francisco". Getting to Zero. San Francisco Department of Public Health. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Allday E (15 September 2017). "Aggressive prevention pays off as new HIV infections in SF hit a record low". SFGate.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Gay Men's Health Crisis (8 August 2016). "GMHC Launches PrEP Ad Campaign in New York City Bus Shelters". Gay Men's Health Crisis. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Glazek C (26 April 2017). "The C.E.O. of H.I.V." The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Cairns G (22 February 2017). "STI rates in PrEP users very high, but evidence that PrEP increases them is inconclusive". AIDSMap.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Highleyman L (24 June 2016). "PrEP use is rising fast in US, but large racial disparities remain". AIDSMap.org. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Gallagher J (3 August 2017). "Prep: HIV 'game-changer' to reach NHS in England from September". BBC. BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Denton PW, Estes JD, Sun Z, Othieno FA, Wei BL, Wege AK, Powell DA, Payne D, Haase AT, Garcia JV (January 2008). "Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis prevents vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in humanized BLT mice". PLoS Medicine. 5 (1): e16. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050016. PMC 2194746. PMID 18198941.

- 1 2 Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, Goicochea P, Casapía M, Guanira-Carranza JV, Ramirez-Cardich ME, Montoya-Herrera O, Fernández T, Veloso VG, Buchbinder SP, Chariyalertsak S, Schechter M, Bekker LG, Mayer KH, Kallás EG, Amico KR, Mulligan K, Bushman LR, Hance RJ, Ganoza C, Defechereux P, Postle B, Wang F, McConnell JJ, Zheng JH, Lee J, Rooney JF, Jaffe HS, Martinez AI, Burns DN, Glidden DV (December 2010). "Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (27): 2587–99. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. PMC 3079639. PMID 21091279.

- 1 2 "PrEP: PK Modeling of Daily TDF/FTC (Truvada) Provides Close to 100% Protection Against HIV Infection". TheBodyPRO.com. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ Heitz D (23 February 2016). "The Possibility of PrEP that's Not Truvada". HIVEqual.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Heitz D (19 October 2015). "PrEP You Don't Swallow: The Future of Anal HIV Prevention". HIVEqual.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Andrei G, Lisco A, Vanpouille C, Introini A, Balestra E, van den Oord J, Cihlar T, Perno CF, Snoeck R, Margolis L, Balzarini J (October 2011). "Topical tenofovir, a microbicide effective against HIV, inhibits herpes simplex virus-2 replication". Cell Host & Microbe. 10 (4): 379–89. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.015. PMC 3201796. PMID 22018238.

- ↑ Mansoor LE, Abdool Karim Q, Yende-Zuma N, MacQueen KM, Baxter C, Madlala BT, Grobler A, Abdool Karim SS (May 2014). "Adherence in the CAPRISA 004 tenofovir gel microbicide trial". AIDS and Behavior. 18 (5): 811–9. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0751-x. PMC 4017080. PMID 24643315.

- ↑ "Adherence Indicators and PrEP Drug Levels in the iPrEx Study" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Celum C, Baeten JM (February 2012). "Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: evolving evidence". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 25 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834ef5ef. PMC 3266126. PMID 22156901.

- ↑ Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. (August 2012). "Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (5): 399–410. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. PMC 3770474. PMID 22784037.

- ↑ Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. (August 2012). "Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (5): 423–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. PMID 22784038.

- ↑ "Top Stories: Poor Adherence Crippled PrEP Efficacy in Women's Study - by Tim Horn". aidsmeds.com. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ "Top Stories: Failed VOICE PrEP Trial Failed to Preempt Lies About Adherence". aidsmeds.com. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. (June 2013). "Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial". Lancet. 381 (9883): 2083–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. PMID 23769234.

- ↑ "Bangkok Tenofovir Study: PrEP for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs" (PDF). CDC Fact Sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, Pialoux G, Cotte L, Charreau I, et al. (December 2015). "On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (23): 2237–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506273. PMID 26624850.

- ↑ Gilles Pialoux. "Ipergay: La Prep "à la demande", ça marche fort (quand on la prend)".

- ↑ Dolling DI, Desai M, McOwan A, Gilson R, Clarke A, Fisher M, et al. (March 2016). "An analysis of baseline data from the PROUD study: an open-label randomised trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis". Trials. 17: 163. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1286-4. PMC 4806447. PMID 27013513.

- ↑ Holt M, Lea T, Mao L, Kolstee J, Zablotska I, Duck T, Allan B, West M, Lee E, Hull P, Grulich A, De Wit J, Prestage G (August 2018). "Community-level changes in condom use and uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by gay and bisexual men in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia: results of repeated behavioural surveillance in 2013-17". The Lancet. HIV. 5 (8): e448–e456. doi:10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30072-9. PMID 29885813.

- ↑ "Does PrEP Use Lead to Higher STI Rates Among Gay and Bi Men?". POZ. 2016-09-02. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

Further reading

- Singh JA, Mills EJ (September 2005). "The abandoned trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: what went wrong?". PLoS Medicine. 2 (9): e234. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020234. PMC 1176237. PMID 16008507.

- Lange JM (September 2005). "We must not let protestors derail trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV". PLoS Medicine. 2 (9): e248. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020248. PMC 1176241. PMID 16008501.

External links

- PrEPWatch PrEP Watch homepage

- CDC CDC Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- CM Mediclinic Thailand What is PrEP?

- Emory University PrEP Locator PrEP Locator

- CDC "Paying for PrEP" Guidelines Paying for PrEP

- Gilead Sciences PrEP Medication Assistance Program Medication Assistance Program

- Gilead Sciences Advancing Access Copayment Program Copayment Coupon Card

- The Game Changer Project Prep HIV