Prakrit

| Prakrit | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Indian subcontinent |

| Linguistic classification |

Indo-European

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | pra |

| Glottolog |

None midd1350 (Middle Indo-Aryan)[1] |

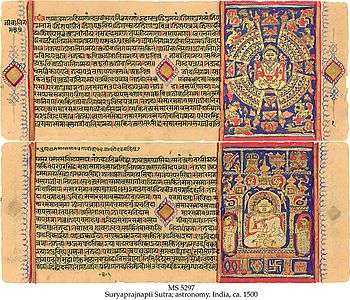

The Prakrits (/ˈprɑːkrɪt/; Sanskrit: प्राकृत prākṛta; Shauraseni: pāuda; Jain Prakrit: pāua) are any of several Middle Indo-Aryan languages formerly spoken in India.[2][3] Texts written in these languages date from the 3rd century BC to the 8th century AD or later.

Overview

The Ardhamagadhi (or simply Magadhi) Prakrit, which was used extensively to write the scriptures of Jainism, is often considered to be the definitive form of Prakrit, while others are considered variants of it. Prakrit grammarians would give the full grammar of Ardhamagadhi first, and then define the other grammars with relation to it. For this reason, courses teaching 'Prakrit' are often regarded as teaching Ardhamagadhi.[4] Pali, the Prakrit used in Theravada Buddhism, tends to be treated as a special exception from the variants of the Ardhamagadhi language, as Classical Sanskrit grammars do not consider it as a Prakrit per se, presumably for sectarian rather than linguistic reasons. Other Prakrits, such as Paiśācī, are reported in old historical sources but are not attested.

Some modern scholars follow this classification by including all Middle Indo-Aryan languages under the rubric of 'Prakrits', while others emphasise the independent development of these languages, often separated from the history of Sanskrit by wide divisions of caste, religion, and geography.[5] While Prakrits were originally seen as 'lower' forms of language, the influence they had on Sanskrit - allowing it to be more easily used by the common people - as well as the converse influence of Sanskrit on the Prakrits, gave Prakrits progressively higher cultural cachet.[6]

The word 'Prakrit' itself has a flexible definition, being defined sometimes as 'original, natural, artless, normal, ordinary, usual' or 'vernacular,' in contrast to the literary and religious orthodoxy of Sanskrit. Alternatively, Prakrit can be taken to mean 'derived from an original,' which means evolved in a natural way. Prakrit is foremost a native term, designating 'vernaculars' as opposed to Sanskrit.

The Prakrits became literary languages, generally patronised by ancient kings of the Hindu kshatriya class, though were still regarded as illegitimate by the orthodoxy. The earliest extant use of Prakrit is in the Edicts of Ashoka on Buddhism (r. 268–232 BCE). It appears as a very significant liturgical language in the form of the Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhists and the Agamas of the Jains, beside countless later grammars, lyrics, plays and epics.[7]

Each variety of Prakrit gradually became associated with a particular patron dynasty, and indeed particular religions, as well as with numerous regional literatures. Every one is today considered to constitute a distinct literary tradition within the history of the subcontinent.

Etymology

According to the dictionary of Monier Monier-Williams (1819–1899), the most frequent meanings of the term prakṛta, from which the word "prakrit" is derived, are "original, natural, normal" and the term is derived from prakṛti, "making or placing before or at first, the original or natural form or condition of anything, original or primary substance". In linguistic terms, this is used in contrast with saṃskṛta, "refined".

Dramatic Prakrits

Dramatic Prakrits were those that were devised specifically for use in dramas and other literature. Whenever dialogue was written in a Prakrit, the reader would also be provided with a Sanskrit translation. None of these Prakrits came into being as vernaculars, but some ended up being used as such when Sanskrit fell out of favor.[8]

The phrase "Dramatic Prakrits" often refers to three most prominent of them: Shauraseni, Magadhi Prakrit, and Maharashtri Prakrit. However, there were a slew of other less commonly used Prakrits that also fall into this category. These include Pracya, Bahliki, Daksinatya, Sakari, Candali, Sabari, Abhiri, Dramili, and Odri. There was a strict structure to the use of these different Prakrits in dramas. Characters each spoke a different Prakrit based on their role and background; for example, Dramili was the language of "forest-dwellers", Sauraseni was spoken by "the heroine and her female friends", and Avanti was spoken by "cheats and rogues".[9]

Maharashtri Prakrit, the ancestor of modern Marathi, is a particularly interesting case. Maharashtri was often used for poetry and as such, diverged from proper Sanskrit grammar mainly to fit the language to the meter of different styles of poetry. The new grammar stuck, which led to the unique flexibility of vowels lengths – amongst other anomalies – in Marathi.[10]

Unusual Prakrits appear in the margins of the Prakritic world: Elu in Sri Lanka and Gāndhārī Prakrit in Gandhara and Central Asia both have unusual phonological and grammatical changes not found in other Prakrits.

List of Prakrits

Research Institutes

In 1955, government of Bihar established at Vaishali, the Research Institute of Prakrit Jainology and Ahimsa with the aim to promote research work in Prakrit.[11]

- National Institute of Prakrit Study and Research. Shravanabelagola, Karnataka, India

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Middle Indo-Aryan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Daniels, p. 377

- ↑ Woolner, Alfred C. (1928). Introduction to Prakrit. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ.,. p. 235. ISBN 9788120801899.

- ↑ Woolner, pg. 6

- ↑ Deshpande, pg. 33

- ↑ Deshpande, pg. 35

- ↑ Woolner, Alfred C. (1928). Introduction to Prakrit (2 (reprint) ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-81-208-0189-9. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Woolner, pg. v.

- ↑ Banerjee, pg. 19-21

- ↑ Deshpande, pg. 36-37

- ↑ Pranamyasagar, Muni (2013). Tirthankar Bhāvna. Vaishali: Prakrit Jainology and Ahimsa Research Institute. p. 198. ISBN 978-93-81403-10-5.

References

- Banerjee, Satya Ranjan. The Eastern School of Prakrit Grammarians : a linguistic study. Calcutta: Vidyasagar Pustak Mandir, 1977.

- Daniels, Peter T., The World's Writing Systems. USA: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Deshpande, Madhav, Sanskrit & Prakrit, sociolinguistic issues. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1993.

- Pischel, R. Grammar of the Prakrit Languages. New York: Motilal Books, 1999.

- Woolner, Alfred C. Introduction to Prakrit, 2nd Edition. Lahore: Punjab University, 1928 (reprint). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, India, 1999.