Kamarupi Prakrit

| Kamarupi Prakrit | |

|---|---|

| Kamrupi Apabhramsa | |

| |

| Pronunciation | Kāmarūpī Prākrit |

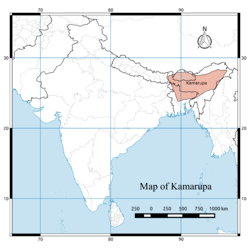

| Region | Kamarupa (North Bengal and Assam) |

| Coordinates | 26°09′N 90°49′E / 26.15°N 90.81°E |

| Ethnicity | Kamarupi people (ancestors of the Indo-Aryan people of Assam and North Bengal) |

| Era | First millennium |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Kamarupi script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

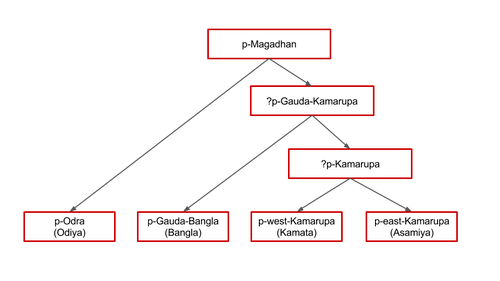

Kamarupi Prakrit[1] is a Middle Indo-Aryan language first spoken in North Bengal and the Brahmaputra valley.[2] This language is the historical ancestor of the Kamta, Rajbanshi and Northern Deshi Bangla lects and the Assamese language;[3][4] and can be dated at least to first millennium,[5] when the ancestor of the proto-Kamata, the parental language of Kamta, Rajbanshi and Northern Deshi Bangla lects, began to develop.[6] This sort of Sporadic Apabhramsa is a mixture of Sanskrit, Prakrit and colloquial dialects of Assam.[7]

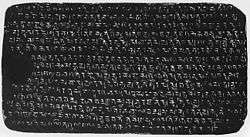

The evidence of this MIA exist in systematic errors in the Sanskrit language used in the Kamarupa inscriptions.[8] A distinguishing characteristic of Kamarupa inscriptions is the replacement of ś and ṣ by s, which is contrary to Vararuci's rule, the main characteristic of Magadhi Prakrit, which warrants that ṣ and s are replaced by ś.[9] Linguists claim this apabhramsa gave rise to various eastern Indo-European languages like modern Assamese.[10][11]

Etymology of various names

The speech is known by different names, which generally consists of two words, prefix such as 'Kamrupi', 'Kamarupi', 'Kamarupa' referring to Kamarupa region and suffixes 'dialect', 'Apabhramsa', sometimes 'Prakrit'. Suniti Kumar Chatterji named it as Kamarupa dialect, as spoken in 'North Bengal and Western Assam' (Kamarupa).[12] Sukumar Sen and others calls it as old Kamrupi dialect;[13][5][14] the speech used in old Kamrup[13] Some scholars termed it as Kamrupi Apabhramsa,[15] Kamarupi language and proto-Kamrupa.

Characteristics

Though the epigraphs were written in classical Sanskrit in kavya style of a high degree, they abound in corrupt and unchaste forms.[17]

- Loss of repha and reduplication of the remaining concerned consonants.

- Shortening of vowels.

- Lengthening of vowels.

- Substitution of one vowel for another.

- Avoidance and irregularity of sandhis.

- Loss of initial vowel.

- Substitution of Y by i.

- Total loss of medial Y.

- Reduplication of consonants immediately followed by r.

- Absence of duplication where it is otherwise necessary.

- Varieties of assimilation.

- Wrong analogy.

- Varied substitution for m and final m.

- Substitution of h by gh and substitution of bh by h.

- Indiscriminate substitution of one sibilant for another.

- Irregularity of declension in case of stems ending in consonants.

- Absence of visarga even where it is invariably necessary.

Apabhramsa

Some linguists claim that there existed a Kamrupi apabhramsa as opposed to the Magadhi apabhramsa from which the three cognate languages---Assamese, Bengali and Odia and Maithili---sprouted. The initial motive comes from extra-linguistic considerations. Kamarupa was the most powerful and formidable kingdom in the region which provided the political and cultural influence for the development of the Kamrupi apabhramsa.

Xuanzang's mention that the language spoken in Kamarupa was a 'little different' from the one spoken in Pundravardhana is provided as evidence that this apabhramsa existed as early as the 5th century. That Kamarupa remained unconquered till the beginning of the Assamese literature in the 14th century points to the possibility that the apabhramsa of the Kamarupa kingdom must have flourished. Archaic forms found in epigraphic records from the Kamarupa period give evidence of this apabhramsa, of which there are numerous examples.

The Buddhist Charyapadas from the 8th to 12th century are claimed by different languages: Assamese, Bengali, Odia and Maithili languages. But the geographical region of its composition was the Kamarupa pitha and many of the composers were Kamarupi siddhas. Therefore, the language in the Charyapadas is the best example of this apabhramsa. H. P. Sastri, who discovered these poems, termed the language sandhya bhasha (twilight language) and this is nothing but the Kamarupi apabhramsa.

Geographical vicinity

Assamese, or more appropriately the old Kamarupi dialect entered into Kamrup or western Assam, where this speech was first characterized as Assamese.[13] Golockchandra Goswami in his An introduction to Assamese phonology writes, "in early Assamese there seems to be one dominant dialect prevailing over the whole country, the Western Assamese dialect." Similarly Upendranath Goswami says, "Assamese entered into Kamarupa or western Assam where this speech was first characterised as Assamese. This is evident from the remarks of Hiuen Tsang who visited the Kingdom of Kamarupa in the first half of the seventh century A.D., during the reign of Bhaskaravarman"

Works

The sample of the old Kamrupi dialect are found in different inscriptions scattered around eastern and northern India, such as Bhaskar Varman's inscriptions. Daka, a native of Lehidangara village of Barpeta composed an authoritative work named Dakabhanita in the 8th century A.D.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "On the basis of many such evidences it is claimed that the Assamese language developed not from the Magadhi but from another parallel variety of Prakrit, which deserves to be called the Kamarupi Prakrit." (Sharma 1978, p. xxv)

- ↑ Sukumar Sen, Ramesh Chandra Nigam (1975), Grammatical sketches of Indian languages with comparative vocabulary and texts, Volume 1, p.33 Assam from ancient times, was known as Kamarupa till the end of the Koch rule (17th century) and ancient Kamarupa comprised the whole of North Bengal including Cooch-Behar, and the Rangpur and Jalpaiguri districts of Bengal. Its permanent western boundary is said to have been the river Karatoya in North Bengal according to the Kalika Purana and Yoginitantra, both devoted to geographical accounts of ancient Kamarupa. So the Aryan language spoken first in Assam was the Kamrupi language spoken in Rangpur, Cooch-Behar, Goalpara, Kamrup district and some parts of Nowgong and Darrang districts. As also put by K.L. Barua "the Kamrupi dialect was originally a variety of eastern Maithili and it was no doubt the spoken Aryan language throughout the kingdon which then included the whole of the Assam Valley and the whole of Northern Bengal with the addition of the Purnea district of Bihar”. It is in this Kamrupi language that the early Assamese literature was mainly written. Up to the seventeenth century as the centre of art, literature and culture were confined within western Assam and the poets and the writers hailed from this part, the language of this part also acquired prestige. The earliest Assamese writer is Hema Saraswati, the author of a small poem, Prahrada Caritra, who composed his verses under his patron, King Durlabhnarayana of Kamatapur who is said to have ruled in the latter part of the 13th century. Rudra Kandali translated Drone Parva under the patronage of King Tamradhvaja of Rangpur. The most considerable poet of the pre-vaisnavite period is Madhava Kandali, who belonged to the present district of Nowgong and rendered the entire Ramayana into Assamese verse under the patronage of king Mahamanikya, a Kachari King of Jayantapura. The golden age in Assamese literature opened with the reign of Naranarayana, the Koch King. He gathered round him at his court at Cooch-Behar a galaxy of learned man. Sankaradeva real founder of Assamese literature and his favourite disciple Madhavadeva worked under his patronage. The other-best known poets and writers of this vaisnavite period namely Rama Sarasvati, Ananta Kandali, Sridhar Kandali, Sarvabhauma Bhattacharyya, Dvija Kalapachandra and Bhattadeva, the founder of the Assamese prose, all hailed from the present district of Kamarupa. During Naranaryana's reign "the Koch power reached its zenith. His kingdom included practically the whole of Kamarupa of the kings of Brahmapala's dynasty with the exception of the eastern portion known as Saumara which formed the Ahom kingdom. Towards the west the kingdom appears to have extended beyond the Karatoya, for according to Abul Fasal, the author of the Akbarnamah, the western boundary of the Koch kingdom was Tirhut. On the south-west the kingdom included the Rangpur district and part of Mymensingh to the east of the river Brahmaputra which then flowed through that district," The Kamrupi language lost its prestige due to reasons mentioned below and has now become a dialect which has been termed as Kamrupi dialect as spoken in the present district of Kamrup.

- ↑ Kamrupa:Chatterjee (1926) uses this term to refer to the stage of linguistic history ancestral to both Asamiya and KRNB. In the present study, Kamrupa is used with same meaning, and is considered not synonymous with KRNB which is a further development (cf section 7.3.4. N.Das (2001) maintains that 'Kamrupa' and 'Kamrupi' is a more fitting title than 'Kamta' for KRNB varieties. However, the term 'Kamrupi' is most popularly used today to denote the western dialect of Asamiya spoken in the greater Kamrup region of Assam (cf. Goswami 1970). It seems well fitted to denote the both (1) the modern lect of the greater Kamrup region of Western Assam (east of the KRNB area), as well as (2) historical lect ancestral to both KRNB and Asamiya. "In this study I refer to the western dialect of Asamiya as Kamrupi, and the historical ancestor of proto-Kamata and proto-Asamiya as proto-Kamrupa." (Toulmin 2006, p. 14)

- ↑ "Eastern Magadhi Prakrit has been divided into four dialect groups by scholars like Dr Chatterji. Kamarupa dialect comprising Assamese and the dialects of North Bengal is one of them. So it becomes necessary to see how much Kamrupi is related to North Bengali" (Goswami 1970, p. 177)

- 1 2 3 Choudhary, Abhay Kant (1971), Early Medieval Village in North-eastern India, A.D. 600-1200:Mainly a Socio-economic Study, Punthi Pustak (India), page 253, pages 411 Daka is stated to have belonged to village Lehidangara near Barpeta in the district of Kamrup, and the Dakabhanita, a work in the old Kamarupi dialect, said to have been composed about the 8th century A D.

- ↑ "Morphological reconstructions in chapter 5-6 provides diagonastic evidence for a common historical stage to the 8 KRNB lects examined in those chapter. On sociohistorical grounds, this stage is termed 'proto-Kamta' in chapter 7 and assigned the chronology of c1250-1550-sandwitched between the establishment of the Kamarupa capital at Kamatapur in 1250 AD and the political (plausibly linguistic) expansion under Koch king Nara Narayan in 1550 AD." (Toulmin 2006, p. 8)

- ↑ Kamarupa Anusandhan Samiti, Journal of the Assam Research Society - Volume 18, 1968 P 81 Though Apabhramsa works in Kamrupi Specimens are not available, yet we can trace the prevalence of early Kamrupi Apabhramsa through the window of archaic froms as found in the grants or Copper-plates mentioned above. This sort of Sporadic Apabhramsa is a mixture of Sanskrit, Prakrit and colloquial dialects of Assam.

- ↑ "... (it shows) that in Ancient Assam there were three languages viz. (1) Sanskrit as the official language and the language of the learned few, (2) Non-Aryan tribal languages of the Austric and Tibeto-Burman families, and (3) a local variety of Prakrit (ie a MIA) wherefrom, in course of time, the modern Assamese language as a MIL, emerged." (Sharma 1978, pp. 0.24-0.28)

- ↑ "The replacement of ṣ and s by ś is one of the main characteristics of the Magadha Prakrit, as warranted by Vararuci's rule, ṣasau śah. But in the Kamarupa inscriptions, we find the reverse of it, i.e the replacement of ś by s as in the word suhańkara, substituted for the Sanskrit śubhańkara in line 32 of the Subhankarpataka grant of Dharmapala." This contrary rule was first pointed out by Dimbeswar Neog (Sharma 1978, p. 0.25), (link)

- ↑ Mrinal Miri, Linguistic situation in North-East India , 2003, Scholars have shown that it is rather through the western Assam dialects that the development of modern Assamese has to be traced.

- ↑ Sukhabilasa Barma, Bhawaiya, ethnomusicological study,2004 Based on the materials of the Linguistic Survey of India, Suniti Kumar Chattopadhyay has divided Eastern Magadhi Prakrit and Apabhramsa into four dialect groups (1) Radha-the language of West Bengal and Orissa (2) Varendra-dialect of North Central Bengal (3) Kamrupi-dialect of Northern Bengal and Assam and (4) Vanga-dialect of East Bengal.

- ↑ Suniti Kumar Chatterji,The origin and development of the Bengali language, Volume 1, One would expect one and identical language to have been current in North Central Bengal (Pundra-vardhana) and North Bengal and West Assam (Kamarupa) in the 7th century, since these tracts, and other parts of Bengal, had almost the same speech.

- 1 2 3 Sukumar Sen, Grammatical sketches of Indian languages with comparative vocabulary and texts, Volume 1, 1975, P 31, Assamese, or more appropriately the old Kamarupi dialect entered into Kamrup or western Assam, where this speech was first characterized as Assamese.

- ↑ Rabindra Panth (2004), Buddhism and Culture of North-East India, p.8, p.p 152 it bears a close resemblance to modern Assamese language, the direct offspring of the old Kamarupi dialect.

- ↑ "This sort of oneness must have helped the growth of a common language which can be termed as Kamrupi Prakrit or Kamrupi Apabhramsa" (Hazarika 1968, p. 80)

- ↑ Proto-Kamta took its inheritance from ?proto-Kamrupa (and before that from ?proto-Gauda-Kamrupa), innovated the unique features ... in 1250-1550 AD" (Toulmin 2006:306)

- ↑ (Sharma 1978, p. 024)

Bibliography

- Hazarika, Parikshit (1968). "The Kamarupi Apabhramsa". Journal of the Assam Research Society. 18: 77–85.

- Goswami, Upendra Nath (1970). A study on Kāmrūpī: a dialect of Assamese. Dept. of Historical Antiquarian Studies, Assam.

- Sharma, Mukunda Madhava (1978). Inscriptions of Ancient Assam. Guwahati, Assam: Gauhati University.

- Toulmin, Mathew W S (2006). Reconstructing linguistic history in a dialect continuum: The Kamta, Rajbanshi, and Northern Deshi Bangla subgroup of Indo-Aryan (Ph.D.). The Australian National University.