Posse comitatus

| Look up posse comitatus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The posse comitatus, in common law, is all able-bodied males over the age of 15 within a specific county, when mobilized in whole or in part by the conservator of peace – usually the sheriff – to suppress lawlessness or defend the county. The posse comitatus originated in ninth century England simultaneous with the creation of the office of sheriff. Though generally obsolete throughout the world, it remains theoretically, and sometimes practically, part of the United States legal system.

Etymology

The term derives from the Latin posse comitātūs, "power" or "force of the county", in English use from the late 16th century, shortened to posse from the mid 17th century.[2] While the original meaning refers to a group of citizens assembled by the authorities to deal with an emergency (such as suppressing a riot or pursuing felons), the term is also used for any force or band, especially with hostile intent, often also figuratively or humorously.[3] In 19th-century usage, posse comitatus also acquires the generalized or figurative meaning.[4] In classic Latin, posse is a contraction of “potesse,” an irregular, subjunctive Latin verb meaning “to be able.” [5] Thus when paired with comitātus, the abstract verbal noun of comito “to accompany,” posse comitatus literally means: “to be able to accompany.” [6] [7] In its earliest days the posse comitatus was subordinate to king, country and local authority. [8]

United Kingdom

English Civil War

In 1642, during the early stages of the English Civil War, local forces were employed everywhere by all sides that could. The powers responsible produced valid written authority, inducing the locals to assemble. The two most common authorities used were the Militia Ordinance on the side of the Parliament and that of the king, the old-fashioned Commissions of Array. But the Royalist leader in Cornwall, Sir Ralph Hopton, indicted the enemy before the grand jury of the county as disturbers of the peace, and had the posse comitatus called out to expel them.

In law

The powers of sheriffs in England and Wales for posse comitatus were codified by section 8 of the Sheriffs Act 1887, the first subsection of which stated that:

Every person in a county shall be ready and apparelled at the command of the sheriff and at the cry of the country to arrest a felon whether within a franchise or without, and in default shall on conviction be liable to a fine, and if default be found in the lord of the franchise he shall forfeit the franchise to the Queen, and if in the bailiff he shall be liable besides the fine to imprisonment for not more than one year, or if he have not whereof to pay the fine, than two years.

This permitted the (high) sheriff of each county to call every citizen to his assistance to catch a person who had committed a felony—that is, a serious crime. It provided for fines for those who did not comply. The provisions for posse comitatus were repealed by the Criminal Law Act 1967.[9] The second subsection provided for the sheriff to take "the power of the county" if he faced resistance whilst executing a writ, and provided for the arrest of resisters.[10] This subsection is still in force.[11]

United States

The posse comitatus power continues to exist in those common law states that have not expressly repealed it by statute. As an example, it is codified in Georgia under OCGA 17-4-24:

Every law enforcement officer is bound to execute the penal warrants given to him to execute. He may summon to his assistance, either in writing or orally, any of the citizens of the neighborhood or county to assist in the execution of such warrants. The acts of the citizens formed as a posse by such officer shall be subject to the same protection and consequences as official acts.

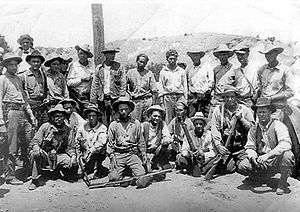

Resorting to the posse comitatus figures often in the plots of Western movies, where the body of men recruited is frequently referred to as a posse. Based on this usage, the word "posse" has come to be used colloquially to refer to various teams, cliques, or gangs, often in pursuit of a crime suspect (on horseback in the westerns), sometimes without legal authority.

In a number of states, especially in the Western United States, sheriffs and other law enforcement agencies have called their civilian auxiliary groups "posses." The Lattimer Massacre of 1897 illustrated the danger of such groups, and thus ended their use in situations of civil unrest. Posse comitatus in America became not an instrument of royal prerogative, but an institution of local self-governance. The posse functioned through, rather than upon, the local popular will.[12] From 1850 to 1878, the federal government had expanded its power over individuals. This was done to safeguard national property rights for slaveholders, emancipate millions of enslaved African Americans, and enforce the doctrine of formal equality. The rise of the federal state, like the marketplace before it, had created contradictory but congruous forces of liberation and compulsion upon individuals.[13] [12]

In the early decades of the republic, before slavery became a major conflict, federal use of posse comitatus in the states was rare and sporadic.[12] But the federal posse comitatus, quite literally, had compelled all of America to accept the legitimacy of slavery.[13] In an exhaustive study of lynching in Colorado, historian Stephen Leonard defines lynching very broadly; he includes the people's courts and even posses (which by definition were led by sheriffs).[12] [14] Indisputably, historical records link violent lawlessness, and even lynchings, to posse comitatus.[15]

In the United States, a federal statute known as the Posse Comitatus Act, enacted in 1878, forbade the use of the United States Army, and through it, its offspring, the United States Air Force, as a posse comitatus or for law enforcement purposes without the approval of Congress. While the act does not explicitly mention the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy has prescribed regulations that are generally construed to give the act force with respect to those services as well.[16] In 2013, a directive [17] from the Secretary of Defense directly addresses this issue: it prohibits the use of the United States Army, the United States Navy, the United States Air Force and the United States Marine Corps for law enforcement.

No such limitation exists on the United States Coast Guard, which can be used for all law enforcement purposes (for example, Coast Guardsmen were used as temporary Air Marshals for many months after the 9/11 attacks) except when, as during World War II, a part of the Coast Guard is placed under the command of the Navy. This part would then fall under the regulations governing the Navy in this matter, rather than those concerning the Coast Guard.

The limitation also does not apply to the National Guard when activated by a state's governor and operating in accordance with Title 32 of the U.S. Code (for example, National Guardsmen were used extensively by state governors during Hurricane Katrina response actions). Conversely, the limitation would apply to the National Guard when activated by the President and operating in accordance with Title 10 of the U.S. Code.[18]

Notable posses

Pierce County, 1856

In response to the dispatch of militia by the Governor of Washington Territory Isaac Stevens to arrest Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territory's Supreme Court who was holding court in the Pierce County Courthouse, the sheriff of Pierce County deputized 50 to 60 citizens for the defense of the court. The standoff between the posse and the militia was ultimately resolved by negotiation and the latter withdrew.[19]

Luzerne County, 1897

Marking the last "significant" use of a posse, in 1897 the sheriff of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania deputized 100 citizens to supplement 50 deputy sheriffs in confronting 400 striking mine workers at the Latimer Mines. Ensuing violence left 19 strikers dead.[20]

Hinsdale County, 1994

In 1994, after violent bank robbers fled from Mineral County, Colorado into remote Hinsdale County, Colorado - which, at the time, had three full-time law enforcement officers for its 500 residents – the county's sheriff summoned the power of the county; more than 100 deputized citizens were directed in house to house searches for the fugitives. The robbers were killed as the posse closed on their location.[21]

Legal status

Case law

Following the Baltimore riot of 1968, 1500 lawsuits were filed against the city of Baltimore seeking compensation for damages sustained due to the failure of the police to suppress the unrest. The city sought declaratory judgment arguing that it could not be liable for any failures of the Baltimore municipal police, as it was an agency of the State of Maryland and the city had no law enforcement authority. In rejecting the argument, the Maryland Court of Appeals observed that Baltimore, as an independent city and – therefore – a county equivalent, was still in possession of the ability to summon the power of the county as that right had not explicitly been repealed by statute and, therefore, remained part of the common law.[22] The court noted:

We are therefore of the opinion that the powers associated with that of a conservator of the peace and the power to form a "posse comitatus," which is included in the powers of a conservator of the peace, were powers available for employment by the City, through the Mayor, should the exercise of reasonable diligence have dictated that they be used.

Statute law

State provisions

Writing in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, David Kopel observed that almost all U.S. states provide statutory authority for sheriffs, or other local officials, to summon the power of the county. In many cases, civil and criminal penalties are prescribed for members of the public who shirk posse duty when summoned; South Carolina provides that "any person refusing to assist as one of the posse . . . shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and, upon conviction shall be fined not less than thirty nor more than one hundred dollars or imprisoned for thirty days" while in New Hampshire a fine of "not more than $20" has been set.[21]

Federal provisions

Title 42 of the United States Code extends the authority to summon the power of the county to United States magistrate judges when necessary to enforce their orders:

... persons so appointed shall have authority to summon and call to their aid the bystanders or posse comitatus of the proper county, or such portion of the land or naval forces of the United States, or of the militia, as may be necessary to the performance of the duty with which they are charged ...

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Posse comitatus. |

References

- ↑ "Ruby, Arizona – A Ghost Town Filled With Mining and Murder". Legends of America. p. 3.

- ↑ OED, s.v. "posse n. 2, posse comitatus.

- ↑ "All the Posse of Hell, cannot violently eject me." T. Fuller, Good Thoughts in Bad Times (1645) I. xv. 39. "A whole posse of the young lady's kindred – brothers, cousins and uncles – stood ready at the street door to usher me upstairs." W. Beckford Portuguese Jrnl. 10 June 1787, p. 72. (cited after OED).

- ↑ "I can lick the whole posser-commertatus of yer. Come on, yer cowards!" Harper's Magazine July 1862, 184/1 (cited after OED).

- ↑ Mueller, Hans-Friedrich (2013). "Latin 101: Learning a Classic Language". The Irregular Verbs Sum and Possum.

- ↑ "Latin Dictionary".

- ↑ "Latin Infinitives" (PDF).

- ↑ Adams, George (1914). "Select Documents of English Constitutional History". The Macmillan Company.

- ↑ Schedule 3, Part III, Criminal Law Act 1967

- ↑ section 8, Sheriffs Act 1887 (as passed)

- ↑ section 8, Sheriffs Act 1887 (as amended)

- 1 2 3 4 Kopel, David B. "The Posse Comitatus And The Office Of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Volume 104, Issue 4; Symposium On Guns In America.

- 1 2 Gautham, Rao (2005). "The Federal Posse Comitatus Doctrine: Slavery, Compulsion, and Statecraft in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America". Law and History Review, Volume 26, Issue 1; Spring 2005, pp. 1–56.

- ↑ “Lynching in Colorado, 1859–1919” (University Press Colorado, 2002).

- ↑ "Hate Normalized: Posse Comitatus?".

- ↑ "Posse Comitatus Act". Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Department of Defense Directive 5525.5". The Posse Comitatus Act.

- ↑ U. S. Code Title 10 and Title 32

- ↑ Floyd, Kaylor (1917). Washington, West of the Cascades: Historical and Descriptive; the Explorers, the Indians, the Pioneers, the Modern, Volume 1. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. pp. 164–166.

- ↑ Miller, Wilbur R. (2012). The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. ISBN 1483305937.

- 1 2 Kopel, David (Fall 2015). "The Posse Comitatus And The Office Of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement". The Posse Comitatus And The Office Of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement. 104 (4).

- ↑ "City of Baltimore v. Silver, 283 A.2d 788 (Md. 1972)". courtlistener.com. Court Listener. Retrieved July 19, 2018.