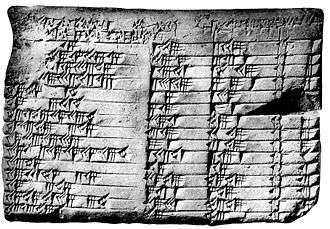

Plimpton 322

Plimpton 322 is a Babylonian clay tablet, notable as containing an example of Babylonian mathematics. It has number 322 in the G.A. Plimpton Collection at Columbia University.[1] This tablet, believed to have been written about 1800 BC, has a table of four columns and 15 rows of numbers in the cuneiform script of the period.

This table lists two of the three numbers in what are now called Pythagorean triples, i.e., integers a, b, and c satisfying a2 + b2 = c2. From a modern perspective, a method for constructing such triples is a significant early achievement, known long before the Greek and Indian mathematicians discovered solutions to this problem. At the same time, one should recall the tablet's author was a scribe, in his day, a professional mathematician; it has been suggested that one of his goals may have been to produce, find, and fix school problems.

There has been significant scholarly debate on the nature and purpose of the tablet. For readable popular treatments of this tablet see Robson (2002) or, more briefly, Conway & Guy (1996). Robson (2001) is a more detailed and technical discussion of the interpretation of the tablet's numbers, with an extensive bibliography.

Provenance and dating

Plimpton 322 is partly broken, approximately 13 cm wide, 9 cm tall, and 2 cm thick. New York publisher George Arthur Plimpton purchased the tablet from an archaeological dealer, Edgar J. Banks, in about 1922, and bequeathed it with the rest of his collection to Columbia University in the mid 1930s. According to Banks, the tablet came from Senkereh, a site in southern Iraq corresponding to the ancient city of Larsa.[2]

The tablet is believed to have been written about 1800 BC, based in part on the style of handwriting used for its cuneiform script: Robson (2002) writes that this handwriting "is typical of documents from southern Iraq of 4000–3500 years ago." More specifically, based on formatting similarities with other tablets from Larsa that have explicit dates written on them, Plimpton 322 might well be from the period 1822–1784 BC.[3] Robson points out that Plimpton 322 was written in the same format as other administrative, rather than mathematical, documents of the period.[4]

Content

The main content of Plimpton 322 is a table of numbers, with four columns and fifteen rows, in Babylonian sexagesimal notation. The fourth column is just a row number, in order from 1 to 15. The second and third columns are completely visible in the surviving tablet. However, the edge of the first column has been broken off, and there are two consistent extrapolations for what the missing digits could be; these interpretations differ only in whether or not each number starts with an additional digit equal to 1. With the differing extrapolations shown in parentheses, these numbers with six errors corrected are

| (1) 59 00 15 | 1 59 | 2 49 | 1 |

| (1) 56 56 58 14 50 06 15 | 56 07 | 1 20 25 | 2 |

| (1) 55 07 41 15 33 45 | 1 16 41 | 1 50 49 | 3 |

| (1) 53 10 29 32 52 16 | 3 31 49 | 5 09 01 | 4 |

| (1) 48 54 01 40 | 1 05 | 1 37 | 5 |

| (1) 47 06 41 40 | 5 19 | 8 01 | 6 |

| (1) 43 11 56 28 26 40 | 38 11 | 59 01 | 7 |

| (1) 41 33 45 14 03 45 | 13 19 | 20 49 | 8 |

| (1) 38 33 36 36 | 8 01 | 12 49 | 9 |

| (1) 35 10 02 28 27 24 26 40 | 1 22 41 | 2 16 01 | 10 |

| (1) 33 45 | 45 | 1 15 | 11 |

| (1) 29 21 54 02 15 | 27 59 | 48 49 | 12 |

| (1) 27 00 03 45 | 2 41 | 4 49 | 13 |

| (1) 25 48 51 35 06 40 | 29 31 | 53 49 | 14 |

| (1) 23 13 46 40 | 56 | 1 46 | 15 |

It is possible that additional columns were present in the broken-off part of the tablet to the left of these columns. Conversion of these numbers from sexagesimal to decimal raises additional ambiguities, as the Babylonian sexagesimal notation did not specify the power of the initial digit of each number. The sixty sexagesimal entries are exact, not truncations or rounded off approximations.

Interpretations

In each row, the number in the second column can be interpreted as the shortest side of a right triangle, and the number in the third column can be interpreted as the hypotenuse of the triangle. The number in the first column is either the fraction (if the "1" is not included) or (if the "1" is included), where denotes the longer side of the same right triangle. Scholars still differ, however, on how these numbers were generated. Below is the decimal translation of the tablet.

| or | Short Side | Diagonal | Row # |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1).9834028 | 119 | 169 | 1 |

| (1).9491586 | 3,367 | 4,825 | 2 |

| (1).9188021 | 4,601 | 6,649 | 3 |

| (1).8862479 | 12,709 | 18,541 | 4 |

| (1).8150077 | 65 | 97 | 5 |

| (1).7851929 | 319 | 481 | 6 |

| (1).7199837 | 2,291 | 3,541 | 7 |

| (1).6927094 | 799 | 1,249 | 8 |

| (1).6426694 | 481 | 769 | 9 |

| (1).5861226 | 4,961 | 8,161 | 10 |

| (1).5625 | 45 | 75 | 11 |

| (1).4894168 | 1,679 | 2,929 | 12 |

| (1).4500174 | 161 | 289 | 13 |

| (1).4302388 | 1,771 | 3,229 | 14 |

| (1).3871605 | 56 | 106 | 15 |

Otto E. Neugebauer (1957) argued for a number-theoretic interpretation, pointing out that this table provides a list of (pairs of numbers from) Pythagorean triples. For instance, line 11 of the table can be interpreted as describing a triangle with short side 3/4 and hypotenuse 5/4, forming the side:hypotenuse ratio of the familiar (3,4,5) right triangle. If p and q are two coprime numbers, one odd and one even, then form a Pythagorean triple, and all Pythagorean triples can be formed in this way or as multiples of a triple formed in this way. For instance, line 11 can be generated by this formula with p = 2 and q = 1. As Neugebauer argues, each line of the tablet can be generated by a pair (p,q) that are both regular numbers, integer divisors of a power of 60. This property of p and q being regular leads to a denominator that is regular, and therefore to a finite sexagesimal representation for the fraction in the first column. Neugebauer's explanation is the one followed e.g. by Conway & Guy (1996). However, as Eleanor Robson (2002) points out, Neugebauer's theory fails to explain how the values of p and q were chosen: there are 92 pairs of coprime regular numbers up to 60, and only 15 entries in the table. In addition, it does not explain why the table entries are in the order they are listed in, nor what the numbers in the first column were used for.

Buck (1980) proposed a possible trigonometric explanation: the values of the first column can be interpreted as the squared secant or tangent (depending on the missing digit) of the angle opposite the short side of the right triangle described by each row, and the rows are sorted by these angles in roughly one-degree increments. In other words, if you take the number in the first column, discounting the (1), and derive its square root, and then divide this into the number in column two, the result will be the length of the long side of the triangle. Consequently, the square root of the number (minus the one) in the first column is what we would today call the tangent of the angle opposite the short side. If the (1) is included, the square root of that number is the secant. [5] However, de Solla Price (1964) points out that the even spacing of the numbers might not have been by design: it could also have arisen merely from the density of regular-number ratios in the range of numbers considered in the table.

In contraposition with these earlier explanations of the tablet, Robson (2002) claims that historical, cultural and linguistic evidence all reveal the tablet to be more likely "a list of regular reciprocal pairs."[6] Robson argues on linguistic grounds that Buck's trigonometric theory is "conceptually anachronistic": it depends on too many other ideas not present in the record of Babylonian mathematics from that time. In 2003, the MAA awarded Robson with the Lester R. Ford Award for her work, stating it is "unlikely that the author of Plimpton 322 was either a professional or amateur mathematician. More likely he seems to have been a teacher and Plimpton 322 a set of exercises."[7] Robson takes an approach that in modern terms would be characterized as algebraic, though she describes it in concrete geometric terms and argues that the Babylonians would also have interpreted this approach geometrically.

Robson bases her interpretation on another tablet, YBC 6967, from roughly the same time and place.[8] This tablet describes a method for solving what we would nowadays describe as quadratic equations of the form, , by steps (described in geometric terms) in which the solver calculates a sequence of intermediate values v1 = c/2, v2 = v12, v3 = 1 + v2, and v4 = v31/2, from which one can calculate x = v4 + v1 and 1/x = v4 - v1.

Robson argues that the columns of Plimpton 322 can be interpreted as the following values, for regular number values of x and 1/x in numerical order:

- v3 in the first column,

- v1 = (x - 1/x)/2 in the second column, and

- v4 = (x + 1/x)/2 in the third column.

In this interpretation, x and 1/x would have appeared on the tablet in the broken-off portion to the left of the first column. For instance, row 11 of Plimpton 322 can be generated in this way for x = 2. Thus, the tablet can be interpreted as giving a sequence of worked-out exercises of the type solved by the method from tablet YBC 6967, and reveals mathematical methods typical of scribal schools of the time, and that it is written in a document format used by administrators in that period.[9] Therefore, Robson argues that the author was probably a scribe, a bureaucrat in Larsa.[10] The repetitive mathematical set-up of the tablet, and of similar tablets such as BM 80209, would have been useful in allowing a teacher to set problems in the same format as each other but with different data. In short, Robson suggests that the tablet would probably have been used by a teacher as a problem set to assign to students.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "158. Cuneiform Tablet. Larsa (Tell Senkereh), Iraq, ca. 1820-1762 BCE. -- RBML, Plimpton Cuneiform 322", Jewels in Her Crown: Treasures of Columbia University Libraries Special Collections, Columbia University, 2004 .

- ↑ Robson (2002), p. 109.

- ↑ Robson (2002), p. 111.

- ↑ Robson (2002), p. 110.

- ↑ See also Joyce, David E. (1995), Plimpton 322 and Maor, Eli (1993), "Plimpton 322: The Earliest Trigonometric Table?", Trigonometric Delights, Princeton University Press, pp. 30–34, ISBN 978-0-691-09541-7, archived from the original on 5 August 2010, retrieved November 28, 2010 .

- ↑ Robson (2002), p. 116.

- ↑ MathFest 2003 Prizes and Awards, Mathematical Association of America, 2003 .

- ↑ Neugebauer & Sachs (1945).

- ↑ Robson (2002), pp. 117–118.

- 1 2 Robson (2002), p. 118.

References

- Buck, R. Creighton (1980), "Sherlock Holmes in Babylon" (PDF), American Mathematical Monthly, Mathematical Association of America, 87 (5): 335–345, doi:10.2307/2321200 .

- Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard K. (1996), The Book of Numbers, Copernicus, pp. 172–176, ISBN 0-387-97993-X .

- Neugebauer, Otto (1957), The Exact Sciences in Antiquity, Dover Publications, pp. 36–40, ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2 .

- Neugebauer, O.; Sachs, A. J. (1945), Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, American Oriental Series, 29, New Haven: American Oriental Society and the American Schools of Oriental Research, pp. 38–41 .

- Robson, Eleanor (August 2001), "Neither Sherlock Holmes nor Babylon: a reassessment of Plimpton 322" (PDF), Historia Math., 28 (3): 167–206, doi:10.1006/hmat.2001.2317, MR 1849797 .

- Robson, Eleanor (February 2002), "Words and pictures: new light on Plimpton 322" (PDF), American Mathematical Monthly, Mathematical Association of America, 109 (2): 105–120, doi:10.2307/2695324, JSTOR 2695324, MR 1903149 .

- de Solla Price, Derek J. (September 1964), "The Babylonian "Pythagorean triangle" tablet", Centaurus, 10: 1–13, Bibcode:1964Cent...10....1D, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1964.tb00385.x, MR 0172779 .

Further reading

- Abdulaziz, Abdulrahman Ali (2010), The Plimpton 322 Tablet and the Babylonian Method of Generating Pythagorean Triples, arXiv:1004.0025, Bibcode:2010arXiv1004.0025A .

- Bruins, Evert M. (1949), "On Plimpton 322, Pythagorean numbers in Babylonian mathematics", Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen Proceedings, 52: 629–632 .

- Bruins, Evert M. (1951), "Pythagorean triads in Babylonian mathematics: The errors on Plimpton 322", Sumer, 11: 117–121 .

- Casselman, Bill (2003), The Babylonian tablet Plimpton 322, University of British Columbia .

- Kirby, Laurence (2011), Plimpton 322: The Ancient Roots of Modern Mathematics (Half-hour video documentary), Baruch College, City University of New York .

Exhibitions

- "Before Pythagoras: The Culture of Old Babylonian Mathematics", Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University, November 12 - December 17, 2010. Includes photo and description of Plimpton 322).

- Rothstein, Edward (November 27, 2010). "Masters of Math, From Old Babylon". New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2010. . Review of "Before Pythagoras" exhibit, mentioning controversy over Plimpton 322.

- "Jewels in Her Crown: Treasures from the Special Collections of Columbia’s Libraries", Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, October 8, 2004 - January 28, 2005. Photo and description of Item 158: Plimpton Cuneiform 322.