Phosphatidylserine

Components of phosphatidylserines: Blue, green: variable fatty acid groups Black: glycerol Red: phosphate Purple: serine | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.368 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Phosphatidylserine (abbreviated Ptd-L-Ser or PS) is a phospholipid and is a component of the cell membrane. It plays a key role in cell cycle signaling, specifically in relation to apoptosis. It is a key pathway for viruses to enter cells via viral apoptotic mimicry.

Structure

Phosphatidylserine is a phospholipid (more specifically a glycerophospholipid). It consists of two fatty acids attached in ester linkage to the first and second carbon of glycerol and serine attached through a phosphodiester linkage to the third carbon of the glycerol.[1]

Phosphatidylserine coming from plants and phosphatidylserine coming from animals differ in fatty acid composition.[2]

Biological function

Cell signaling

Phosphatidylserine(s) are actively held facing the cytosolic (inner) side of the cell membrane by the enzyme flippase. However, when a cell undergoes apoptosis, phosphatidylserine is no longer restricted to the cytosolic side by flippase. Instead scramblase catalyzes the rapid exchange of phosphatidylserine between the two sides. When the phosphatidylserines flip to the extracellular (outer) surface of the cell, they act as a signal for macrophages to engulf the cells.[3]

Coagulation

Phosphatidylserine plays a role in blood coagulation (also known as clotting). When circulating platelets encounter the site of an injury, collagen and thrombin -mediated activation causes externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner membrane layer, where it serves as a pro-coagulant surface.[4] This surface acts to orient coagulation proteases, specifically tissue factor (TF) and factor VII, facilitating further proteolysis, activation of factor X, and ultimately generating thrombin.[4]

In the coagulation disorder Scott syndrome, the mechanism in platelets for transportation of PS from the inner platelet membrane surface to the outer membrane surface is defective.[5] It is characterized as a mild bleeding disorder stemming from the patient's deficiency in thrombin synthesis.[6]

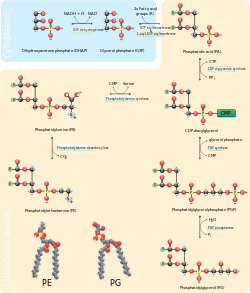

Biosynthesis

Phosphatidylserine is biosynthesized in bacteria by condensing the amino acid serine with CDP (cytidine diphosphate)-activated phosphatidic acid.[7] In mammals, phosphatidylserine is produced by base-exchange reactions with phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine. Conversely, phosphatidylserine can also give rise to phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine, although in animals the pathway to generate phosphatidylcholine from phosphatidylserine only operates in the liver.[8]

Dietary sources

The average daily phosphatidylserine (PS) intake from diet in Western countries is estimated to be 130 mg. PS may be found in meat and fish. Only small amounts of PS can be found in dairy products or in vegetables, with the exception of white beans and soy lecithin.

Table 1. PS content in different foods.[9] Soy products are not in this table, because commercial PS is made by enzymatically converting soy phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) to phosphatidylserine, rather than purifying phosphatidylserine from soy.

| Food | PS Content in mg/100 g |

|---|---|

| Bovine brain | 713 |

| Atlantic mackerel | 480 |

| Chicken heart | 414 |

| Atlantic herring | 360 |

| Eel | 335 |

| Offal (average value) | 305 |

| Pig's spleen | 239 |

| Pig's kidney | 218 |

| Tuna | 194 |

| Chicken leg, with skin, without bone | 134 |

| Chicken liver | 123 |

| White beans | 107 |

| Soft-shell clam | 87 |

| Chicken breast, with skin | 85 |

| Mullet | 76 |

| Veal | 72 |

| Beef | 69 |

| Pork | 57 |

| Pig's liver | 50 |

| Turkey leg, without skin or bone | 50 |

| Turkey breast without skin | 45 |

| Crayfish | 40 |

| Cuttlefish | 31 |

| Atlantic cod | 28 |

| Anchovy | 25 |

| Whole grain barley | 20 |

| European hake | 17 |

| European pilchard (sardine) | 16 |

| Trout | 14 |

| Rice (unpolished) | 3 |

| Carrot | 2 |

| Ewe's Milk | 2 |

| Cow's Milk (whole, 3.5% fat) | 1 |

| Potato | 1 |

Supplementation

Health claims

A panel of the European Food Safety Authority concluded that a cause and effect relationship cannot be established between the consumption of phosphatidylserine and "memory and cognitive functioning in the elderly”, “mental health/cognitive function” and “stress reduction and enhanced memory function”.[2] The reason is that bovine brain cortex- and soy-based phosphatidylserine are different substances and might, therefore, have different biological activities. Therefore, the results of studies using PS coming from different sources cannot be generalized.[2]

Cognition

In May, 2003 the Food and Drug Administration gave "qualified health claim" status to phosphatidylserine thus allowing labels to state "consumption of phosphatidylserine may reduce the risk of dementia and cognitive dysfunction in the elderly" along with the disclaimer "very limited and preliminary scientific research suggests that phosphatidylserine may reduce the risk of cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. FDA concludes that there is little scientific evidence supporting this claim."[10][11]

The FDA declared that "based on its evaluation of the totality of the publicly available scientific evidence, the agency concludes that there is not significant scientific agreement among qualified experts that a relationship exists between phosphatidylserine and reduced risk of dementia or cognitive dysfunction".[10] The FDA also noted "Of the 10 intervention studies that formed the basis of FDA's evaluation, all were seriously flawed or limited in their reliability in one or more ways", concluding that "most of the evidence does not support a relationship between phosphatidylserine and reduced risk of dementia or cognitive dysfunction, and that the evidence that does support such a relationship is very limited and preliminary".[10]

Early studies of phosphatidylserine on memory and cognition used a supplement which isolated the molecule from the bovine brain. Currently, most commercially available products are made from cabbage or soybeans because of concerns about mad cow disease in bovine brain tissue.[12] These plant-based products have a similar, but not identical chemical structure to the bovine derived supplements; for example, the FDA notes "the phosphatidylserine molecule from soy lecithin contains mainly polyunsaturated acids, while the phosphatidylserine molecule from bovine brain cortex contains mainly saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids".[10]

A preliminary study in rats in 1999 indicated that the soy derived phosphatidylserine supplement was as effective as the bovine derived supplement in one of three behavioral tests.[13][14] However, clinical trials in humans prior to 2010 found that "a daily supplement of S-PS [soybean-derived phosphatidylserine] does not affect memory or other cognitive functions in older individuals with memory complaints."[15] Then in 2010, a Japanese randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial examining a sample of 78 subjects with mild cognitive impairment after a longer 6-month period found improvement in the group with the lowest memory test scores when soy-based PS was administered orally, concluding that supplementation could be useful "for preventing dementia in people with memory complaints."[16] While further study is obviously needed, many people maintain that soy-derived phosphatidylserine has the ability to positively influence cognitive function in various ways, from improving memory function to staving off age-related cognitive decline[17].

Safety

Traditionally, PS supplements were derived from bovine cortex (BC-PS). However, due to the risk of potential transfer of infectious diseases, soy-derived PS (S-PS) supplements have been used as an alternative.[12] Soy-derived PS is designated Generally Recognized As Safe by the FDA. A 2002 safety report determined supplementation in elder people at a dosage of 200 mg three times daily to be safe.[18]

References

- ↑ Nelson, David; Cox, Michael. Lehninger Principles of biochemistry (5 ed.). W.H Freeman and company. p. 350. ISBN 9781429208925.

- 1 2 3 EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2010-10-01). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to phosphatidyl serine (ID 552, 711, 734, 1632, 1927) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 8 (10): 1749. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1749. ISSN 1831-4732.

- ↑ Verhoven, B.; Schlegel, R. A.; Williamson, P (1 November 1995). "Mechanisms of phosphatidylserine exposure, a phagocyte recognition signal, on apoptotic T lymphocytes" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Medicine. 182 (5): 1597–601. doi:10.1084/jem.182.5.1597. PMC 2192221. PMID 7595231. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- 1 2 Lentz, B. R. (September 2003). "Exposure of platelet membrane phosphatidylserine regulates blood coagulation". Prog Lipid Res. 42 (5): 423–438. doi:10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00025-0. PMID 12814644.

- ↑ Zwaal FA, Comfurius P, Bevers EM. Scott syndrome, a bleeding disorder caused by defective scrambling of membrane phospholipids. Biochem Bioph Acta 2004; 1636:119-128

- ↑ Weiss HJ. Scott syndrome: a disorder of platelet coagulant activity (PCA). Sem Hemat 1994; 31:312-319

- ↑ Christie, William W. (4 April 2013). "Phosphatidylserine and Related Lipids: Structure, Occurrence, Biochemistry and Analysis" (PDF). The American Oil Chemists’ Society Lipid Library. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Christie, William W. (12 June 2014). "Phosphatidylcholine and Related Lipids: Structure, Occurrence, Biochemistry and Analysis" (PDF). The American Oil Chemists’ Society Lipid Library. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Souci SW, Fachmann E, Kraut H (2008). Food Composition and Nutrition Tables. Medpharm Scientific Publishers Stuttgart.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor, Christine L. (May 13, 2003). "Phosphatidylserine and Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia (Qualified Health Claim: Final Decision Letter)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ "Summary of Qualified Health Claims Subject to Enforcement Discretion - Qualified Claims About Cognitive Function".

- 1 2 Smith, Glenn (2 June 2014). "Can phosphatidylserine improve memory and cognitive function in people with Alzheimer's disease?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ Blokland, A; Honig W; Brouns F; Jolles J (October 1999). "Cognition-enhancing properties of subchronic phosphatidylserine (PS) treatment in middle-aged rats: comparison of bovine cortex PS with egg PS and soybean PS". Nutrition. 15 (10): 778–83. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00157-4. PMID 10501292.

- ↑ Crook, T. H.; R. M. Klatz (ed) (1998). Treatment of Age-Related Cognitive Decline: Effects of Phosphatidylserine in Anti-Aging Medical Therapeutics. 2. Chicago: Health Quest Publications. pp. 20–29.

- ↑ Jorissen, BL; Brouns F, Van Boxtel MP, Ponds RW, Verhey FR, Jolles J, Riedel WJ. (2001). "The influence of soy-derived phosphatidylserine on cognition in age-associated memory impairment". Nutritional Neuroscience. 4 (2): 121–34. PMID 11842880.

- ↑ Kato-Kataoka, Akito; Sakai, Masashi; Ebina, Rika; Nonaka, Chiaki; Asano, Tsuguyoshi; Miyamori, Takashi (November 2010). "Soybean-Derived Phosphatidylserine Improves Memory Function of the Elderly Japanese Subjects with Memory Complaints". Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 47 (3): 246–255. doi:10.3164/jcbn.10-62. ISSN 0912-0009. PMC 2966935. PMID 21103034.

- ↑ "Phosphatidylserine For Brain Function - Everything You Need To Know | Natural Nootropic". Natural Nootropic. 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ Jorissen BL, Brouns F, Van Boxtel MP, Riedel WJ; Brouns; Van Boxtel; Riedel (October 2002). "Safety of soy-derived phosphatidylserine in elderly people". Nutritional Neuroscience. 5 (5): 337–43. doi:10.1080/1028415021000033802. PMID 12385596.

External links

- DrugBank info page

- FDA Qualified Health Claim Phosphatidylserine and Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia

- Phosphatidylserines at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)