Peter Norman

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Peter George Norman |

| Born |

15 June 1942 Coburg, Victoria, Australia |

| Died |

3 October 2006 (aged 64) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Height | 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) |

| Weight | 73 kg (161 lb) |

| Sport | |

| Country |

|

| Sport | Athletics |

| Event(s) | Sprint |

| Club | East Melbourne Harriers[1] |

| Achievements and titles | |

| Personal best(s) | 20.06 s (200 m, 1968)[1] |

Medal record

| |

Peter George Norman (15 June 1942 – 3 October 2006) was an Australian track athlete. He won the silver medal in the 200 metres at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, with a time of 20.06 seconds which remains the Oceanian 200 metres record.[2] He was a five-time Australian 200 m champion.[3]

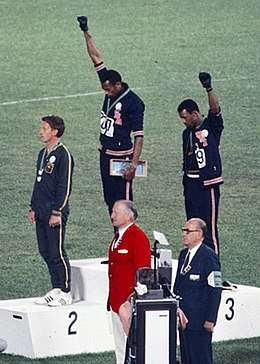

He is the third athlete pictured in a famous photograph of the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute during the medal ceremony for the 200-metre event, where he wore a badge of the Olympic Project for Human Rights in support of fellow athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith. Norman faced backlash in Australia for his part in the protest, and was not selected for the following 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich despite qualifying (a claim disputed by the Australian Olympic Committee). He retired from the sport soon after.[4]

Biography

Early life

Norman grew up in a devout Salvation Army family[5] living in Coburg, a suburb of Melbourne in Victoria. Initially an apprentice butcher, Norman later became a teacher, and worked for the Victorian Department of Sport and Recreation towards the end of his life.[6]

During his athletics career Norman was coached by Neville Sillitoe.[5]

1968 Summer Olympics

The 200 metres at the 1968 Olympics started on 15 October and finished on 16 October; Norman won his heat in a time of 20.17 seconds which was briefly an Olympic record.[7] He won his quarter final and was second in the semi.

On the morning of 16 October, U.S. athlete Tommie Smith won the 200 metre final with a world-record time of 19.83 seconds.[8][9] Norman finished second in a time of 20.06 s, after catching and eventually passing U.S. athlete John Carlos at the finish line. Carlos finished in third place in 20.10 s. Norman's time was his all-time personal best[1] and an Australian record that still stands.

After the race, the three athletes went to the medal podium for their medals to be presented by David Cecil, 6th Marquess of Exeter. On the podium, during the playing of "The Star-Spangled Banner", Smith and Carlos famously joined in a Black Power salute. This salute was later described in Tommie Smith's autobiography as a Human Rights salute, not a Black Power salute.

Norman wore a badge on the podium in support of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). After the final, Carlos and Smith had told Norman what they were planning to do during the ceremony. As journalist Martin Flanagan wrote; "They asked Norman if he believed in human rights. He said he did. They asked him if he believed in God. Norman, who came from a Salvation Army background, said he believed strongly in God. We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat. He said, 'I'll stand with you'." Carlos said he expected to see fear in Norman's eyes. He didn't; "I saw love."[10] On the way out to the medal ceremony, Norman saw the OPHR badge being worn by Paul Hoffman, a white member of the US Rowing Team, and asked him if he could wear it.[11] It was Norman who suggested that Smith and Carlos share the black gloves used in their salute, after Carlos left his pair in the Olympic Village.[4] This is the reason for Smith raising his right fist, while Carlos raised his left.

Later career

Before the 1968 Olympics Norman was a trainer for West Brunswick Australian rules football club as a way of keeping fit over winter during the athletic circuit's off season. After 1968 he played 67 games for West Brunswick between 1972 and 1977 before coaching an under 19 team in 1978.

In 1985, Norman contracted gangrene after tearing his Achilles tendon during a charity race, which nearly led to his leg being amputated. Depression, heavy drinking and pain killer addiction followed.[12]

Treatment after 1968

After the salute, it has been claimed that Norman's career suffered greatly. A 2012 CNN profile said that "he returned home to Australia a pariah, suffering unofficial sanction and ridicule as the Black Power salute's forgotten man. He never ran in the Olympics again."[13] He was not selected for the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972 despite turning in adequate times, and was not welcomed even three decades later at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.[14][15][16] Carlos later stated that "If we [Carlos and Smith] were getting beat up, Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone."[15][16]

The Australian Olympic Committee maintains that Norman was not selected for the 1972 Olympics because he did not meet the selection standard which entailed an athlete equalling or bettering the Olympic qualifying standard (20.9)[17] and performing creditably at the Australian Athletics Championships.[18] Norman ran several qualifying times from 1969-1971[19] but he finished third in the 1972 Australian Athletics Championships behind Greg Lewis and Gary Eddy in a time of 21.6.[19]

Contemporary reports show mixed opinion on whether Norman should have been sent to the Munich Olympics. After coming third in the trials, Norman commented: "All I had to do was to win, even in a slow time, and I think I would have been off to Munich".[20] The Age correspondent wrote Norman "probably ran himself out of the team at the National titles"; but also noted he was injured; and continued, "If the selectors do the right thing, Norman should still be on the plane to Munich."[20] On the other hand, Australasian Amateur Athletics' magazine stated "The dilemma for selectors here was how could they select Norman and not Lewis. Pity that Peter did not win because that would have been the only requirement for a Munich ticket".[21]

2012 Parliamentary apology

In August 2012, the Australian Parliament debated a motion to provide a posthumous apology to Norman.[22][23][24] On 11 October 2012 the Australian House of Representatives passed the wording of an official apology that read:[25]

| “ | 15 PETER NORMAN

The order of the day having been read for the resumption of the debate on the motion of Dr Leigh—

That this House: |

” |

In a 2012 interview, Carlos said:[26]

| “ | There's no-one in the nation of Australia that should be honoured, recognised, appreciated more than Peter Norman for his humanitarian concerns, his character, his strength and his willingness to be a sacrificial lamb for justice. | ” |

Apology claims disputed

The Australian Olympic Committee has disputed the claims made in the Australian Parliament apology about Norman paying a price in supporting Carlos and Smith. The AOC made the following comments:

- Norman was not punished by the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC).[27] He was cautioned by Chef de Mission Judy Patching on the evening of the medal ceremony and then given as many tickets as he wanted to go and watch a hockey match.[27]

- Norman was not selected for the 1972 Munich Olympics as he did not meet the selection standard which entailed an athlete equalling or bettering the Olympic qualifying standard (20.9)[28] and performing creditably at the Australian Athletics Championships.[29] Norman ran several qualifying times from 1969-1971[19] but he finished third in the 1972 Australian Athletics Championships behind Greg Lewis and Gary Eddy in a time of 21.6.[19]

- In the lead up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the AOC stated "Norman was involved in numerous Olympic events in his home city of Melbourne. He announced several teams for the AOC in Melbourne and was on the stage in his Mexico 1968 blazer congratulating athletes. He was acknowledged as an Olympian and the AOC valued his contribution."[27] Due to cost considerations, the AOC did not have the resources to bring all Australian Olympians to Sydney and Norman was offered the same chance to buy tickets as other Australian Olympians. The AOC did not believe that Norman was owed an apology.[30]

It has been stated that United States authorities invited him to participate in the 2000 Sydney Olympics after they found out he was not attending.[31] On 17 October 2003, San Jose State University unveiled a statue commemorating the 1968 Olympic protest; Norman was not included as part of the statue itself – his empty podium spot intended for others viewing the statue to "take a stand" – but was invited to deliver a speech at the ceremony.[6]

Death

Norman died of a heart attack on 3 October 2006 in Melbourne at the age of 64.[11] The US Track and Field Federation proclaimed 9 October 2006, the date of his funeral, as Peter Norman Day. Thirty-eight years after the three made history, both Smith and Carlos gave eulogies and were pallbearers at Norman's funeral.[6] At the time of his death, Norman was survived by his second wife, Jan, and their daughters Belinda and Emma, his first wife, Ruth, and children Gary, Sandra and Janita and four grandchildren.[5]

Competitive Record

International competitions

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Commonwealth Games | Perth, Australia | 6th S/F 1 ; 12/43 | 220 yards | 21.8(22.03)(−2.8) |

| 1966 | Commonwealth Games | Kingston, Jamaica | 6th Q/F ; 29/54 | 100 yards | 10.2(10.27)(−5.0) |

| 6th S/F 1 ; 10/56 | 220 yards | 21.2(0.0) | |||

| 3rd | 4×110 yards | 40.0 | |||

| 5th | 4×440 yards | 3:12.2 | |||

| 1968 | Olympic Games | Mexico City, Mexico | 2nd | 200 m | 20.0 (20.06)(+0.9) |

| 1969 | Pacific Conference Games | Tokyo, Japan | 4th | 100 m | 10.8(−0.1) |

| 1st | 200 m | 21.0(−0.1) | |||

| 1st | 4 × 100 m | 40.8 | |||

| 1970 | Commonwealth Games | Edinburgh, Scotland | 5th | 200 m | 20.86(+1.7) |

| DNF Heat1 ; 14th | 4 × 100 m | Dropped baton |

National championships

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965/66 | Australian Championships | Perth, Western Australia | 1st | 200 m | 20.9 (−1.2) |

| 1966/67 | Australian Championships | Adelaide, South Australia | 1st | 200 m | 21.3 |

| 1967/68 | Australian Championships | Sydney, New South Wales | 1st | 200 m | 20.5 (0.0) |

| 1968/69 | Australian Championships | Melbourne, Victoria | 2nd | 100 m | 10.6 (−0.5) |

| 1st | 200 m | 21.3 (−3.1) | |||

| 1969/70 | Australian Championships | Adelaide, South Australia | 1st | 200 m | 21.0 (−2.1) |

| 1971/72 | Australian Championships | Perth, Western Australia | 3rd | 200 m | 21.6 |

Legacy

Norman's nephew Matt Norman directed and produced the cinema-released documentary Salute (2008) about the three runners through Paramount Pictures and Transmission Films. Paul Byrnes in his Sydney Morning Herald review of Salute says that the film makes it clear why Norman stood with the other two athletes. Byrnes writes, "He was a devout Christian, raised in the Salvation Army [and] believed passionately in equality for all, regardless of colour, creed or religion—the Olympic code".[33]

An airbrush mural of the trio on podium was painted in 2000 in the inner-city suburb of Newtown in Sydney.[A 1] Silvio Offria, who allowed an artist known only as "Donald" to paint the mural on his house in Leamington Lane, said Norman came to see the mural, "He came and had his photo taken, he was very happy."[34] The monochrome tribute, captioned "THREE PROUD PEOPLE MEXICO 68," was under threat of demolition in 2010 to make way for a rail tunnel[34] but is now listed as an item of heritage significance.[35]

Recognition

- 1999 – Sport Australia Hall of Fame inductee

- 2000 – Australian Sports Medal

- 2010 – Athletics Australia Hall of Fame inductee

- 2018 – Order of Merit from Australian Olympic Committee [36]

- 2018 - Athletics Australia in partnership with the Victorian Government announced the building and erecting a bronze statue of Norman at Lakeside Stadium in Melbourne. The statue will honour Norman’s legacy as an athlete and advocate for human rights. [37]

References

- Annotations

- ↑ 39 Pine Street, Newtown, New South Wales, Australia

- Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Peter Norman. sports-reference.com

- ↑ Carlson 2006

- ↑ Associated Press 2006

- 1 2 Frost 2008

- 1 2 3 Hurst, Mike (8 Oct 2006). "Peter Norman's Olympic statement". Courier Mail. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hawker 2008

- ↑ Irwin 2012

- ↑ Athletics at the 1968 Ciudad de México Summer Games: Men's 200 metres. sports-reference.com

- ↑ New Scientist 1981, p. 285

- ↑ Flanagan 2006

- 1 2 Hurst 2006

- ↑ Johnstone & Norman 2008

- ↑ CNN, By James Montague,. "The third man: The forgotten Black Power hero - CNN".

- ↑ Georgakis, Steve. "'I will stand with you': finally, an apology to Peter Norman".

- 1 2 Vincent, Donovan (7 August 2016). "The forgotten story behind the 'black power' photo from 1968 Olympics" – via Toronto Star.

- 1 2 "Divided by their colour, united by the cause". 1 August 2016.

- ↑ "IOC Releases 1972 Olympic Standards". Track and Field News: 24. May 1971.

- ↑ "A sprint hope who ran foul of Olympic starters gun". National Times (3–8 April 1972 p.28).

- 1 2 3 4 Messenger, Robert (24 August 2012). "Leigh sprints into wrong lane over Norman". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Peter may have lost team place" (PDF). The Age. 27 March 1972. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "National Championships - 24-25 March 1972, Perry Lakes Stadium, Perth". Australasian Amateur Athletics: 2–3. April 1972.

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph 2012

- ↑ Australian Associated Press 2012

- ↑ Whiteman 2012

- ↑ Parliament of Australia 2012, p. 1865

- ↑ Carlos & Eastley 2012

- 1 2 3 "Peter Norman not shunned by AOC". Australian Olympic Committee News, 6 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "IOC Releases 1972 Olympic Standards". Track and Field News: 24. May 1971.

- ↑ "A sprint hope who ran foul of Olympic starters gun". National Times (3–8 April 1972 p.28).

- ↑ Whiteman, Hilary (21 August 2012). "Apology urged for Australian Olympian in 1968 black power protest". CNN. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Schembri 2008

- 1 2 "Peter Norman". athhistory.imgstg.com. Australia Athletics Historical Results. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ Byrnes, Paul (17 July 2008). "Salute". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- 1 2 Tovey 2010

- ↑ City of Sydney 2010, p. 27

- ↑ "Aussie sprinter who stood on podium during 1968 black-power salute to be recognised". Stuff (Fairfax). 28 April 2018.

- ↑ "Peter Norman Statue to be built". Athletics Australia website. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- References

- Australian Associated Press (20 August 2012). "Sprinter Norman may get apology". The Age. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Associated Press (4 October 2006). "Peter Norman; Australian Medalist in '68 Games". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Carlos, John; Eastley, Tony (21 August 2012). "John Carlos: No Australian finer than Peter Norman". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Carlson, Michael (5 October 2006). "Unlikely Australian participant in black athletes' Olympic civil rights protest". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- City of Sydney (October 2010). "Heritage Assessment of the Three Proud People mural" (PDF). City of Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Flanagan, Martin (10 October 2006). "Tell Your Kids About Peter Norman". The Age. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Frost, Caroline (17 October 2008). "The other man on the podium". BBC News. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Hawker, Phillippa (15 July 2008). "Salute to a champion". The Age. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Hurst, Mike (8 October 2006). "Peter Norman's Olympic statement". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Irwin, James D. (27 September 2012). "The Humans Raced". The Weeklings. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Johnstone, Damian; Norman, Matt T. (2008). A Race to Remember: The Peter Norman Story (2008 ed.). JoJo Publishing. ISBN 9780980495027. - Total pages: 320

- Lucas, Dean (22 May 2013). "Black Power". Famous Pictures Collection. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- New Scientist (1981). New Scientist Vol. 90, No. 1251. New Scientist (30 April 1981 ed.). ISSN 0262-4079. - Total pages: 64

- Schembri, Jim (17 July 2008). "It's a film worthy not only of our praise, but of our thanks". The Age. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Parliament of Australia (11 October 2012). "THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 138". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- The Daily Telegraph (20 August 2012). "Olympian apology on agenda". Herald Sun. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Tovey, Josephine (27 July 2010). "Last stand for Newtown's 'three proud people'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Webster, Andrew; Norman, Matt T. (2018). The Peter Norman Story (2018 ed.). Pan MacMillan Australia. ISBN 9781925481365. - Total pages: 304

- Whiteman, Hilary (21 August 2012). "Apology urged for Australian Olympian in 1968 black power protest". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Norman. |