Paul von Rennenkampf

| Edler Paul von Rennenkampf | |

|---|---|

Paul von Rennenkampf in 1910 | |

|

In office 20 January [O.S. 7] 1913 – 19 July [O.S. 6] 1914 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | Fyodor Martsov |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

29 April [O.S. 17] 1854 Konuvere Manor (et), Konuvere , Governorate of Estonia, Russian Empire |

| Died |

1 April 1918 (aged 63) Taganrog, Russian SFSR |

| Resting place | Taganrog Old Cemetery[1][2] |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1870–1915 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

36th Akhtyrka Dragoon Regiment 1st Separate Cavalry Brigade Transbaikal Cossack Army 7th Siberian Army Corps 3rd Siberian Army Corps 3rd Army Corps Vilna Military District (1913-1914) 1st Army |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Russian: Foreign: |

Paul Georg Edler[3] von Rennenkampff (Russian: Па́вел-Георг Ка́рлович Ренненка́мпф, Pavel-Georg Karlovich Rennenkampf; 29 April [O.S. 17] 1854 – 1 April 1918), more commonly known as Paul von Rennenkampf in English, was a Baltic German general of the Imperial Russian Army who commanded the 1st Army in the Invasion of East Prussia during the initial stage of the Eastern front of World War I. He also served as the last commander of the Vilna Military District.

Rennenkampf gained a reputation as a capable cavalry commander during the Boxer Rebellion and the Russo-Japanese War. Following service in the latter, he led the detachment that suppressed the Chita Republic during the 1905 Russian Revolution. This earned him further promotion, and by the outbreak of World War I Rennenkampf was commander of the Vilna Military District, whose forces were used to form the 1st Army under his command. He led the 1st Army in the invasion of East Prussia, but was relieved of command after defeats at Tannenberg, the Masurian Lakes and Łódź, although he was later proved innocent for the mistakes made in the Battle at Łódź. Exonerated by an official inquiry into his actions, Rennenkampf was shot by the Bolsheviks in Taganrog during the Red Terror in 1918.

Biography

Origin

Paul Georg Edler von Rennenkampff was born 29 April 1854 in the Konuvere Manor (et) (now in the small village of Konuvere in Märjamaa Parish, Estonia) in the Governorate of Estonia as the sixth child of Baltic German Captain Karl Gustav Edler von Rennenkampff and noblewoman Ingeborg Freiin von Stackelberg from the Baltic German Stackelberg family (de), he came from the Baltic German noble Rennenkampff family (de) and believed in Lutheran faith. The Rennenkampff Family originated from the Holy Roman Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück and was predominantly Lutherans. The first commonly known ancestor of the family was of a man named Johann Remenkampe living in Münster, and the family was made famous by Joachim Rennenkampff, a jurist working as a councilor of the educations in Riga during the mid-17th Centery, also the common ancestor of the Baltic family was Jakob Georg von Rennenkampff. The family split into two branches: the senior Palloper line and the junior Helmet line, the junior branch was granted with imperial nobility and imperial title of Edler by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in Vienna back in 1728, while the senior branch was granted imperial nobility by Emperor Rudolf II earlier in 1602, they were enrolled into the Livonian, Estonian and Courland nobility in the years 1745, 1752 and 1801 respectively. In 1908, Karl Otto Woldemar Magnus and his brother Eduard Ernst von Rennenkampff were enrolled into Prussian nobility by Wilhelm II. The Rennenkampff family also had a long history of service in the Russian Empire, including Paul's father and his two great-uncles, Paul Andreas and Karl Friedrich, who both served in the Imperial Russian Army during the early 19th century. As well as being one of the largest landowners in the Russian Baltics (they had over 90,000 hectares worth of land during the 18th Centery). [5][6][7] And on his mother’s side was the Stackelberg family, which the common ancestor was Carl Adam von Stackelberg, a Swedish cavalry officer and participant of The Great Northern War[8], making him a fifth cousin of the famous Russo-Japanese War general Georg von Stackelberg.[9]

Early career

As a youth, Rennenkampf attended the Estonian Knight and Cathedral School in Reval (et) (German: Die Estländische Ritter- und Domschule zu Reval) (present-day Tallinn Toomkool), a German-speaking school built especially for Baltic Germans, he was also fluent at many languages including German and Russian. Upon graduation, he joined the military as a non-commissioned officer in the 89th Infantry Regiment. He graduated the Helsingforsky infantry school of the Junkers in Helsingfors (now Helsinki). He began his military career with the Lithuanian 5th Lancers Regiment. He graduated at the head of his class from the Nikolaev Academy of General Staff in St. Petersburg (or at the first category) in 1881. From late November to late August 1884, he was an over-officer for instruction of the 14th Army Corps. In late September 1886, he was the chief of staff of the Warsaw Military District serving under commander-in-chief of the military district, then general and later field marshal, Count Gurko. In early 1888, he was appointed to the Kazan Military District, Rennenkampf subsequently became the senior adjutant to the headquarters of the Don Cossacks. In late October of 1889, he was appointed headquarters officer for special assignment at the 2nd Army Corps headquarters. In late March of 1890, he was appointed the chief of staff of the Osowiec Fortress in Russian Poland. The same year he was promoted to colonel, after which he served in several minor regiment until late November 1899, when he was appointed chief of staff of the Transbaikal region, and was promoted to major general.

Boxer Rebellion

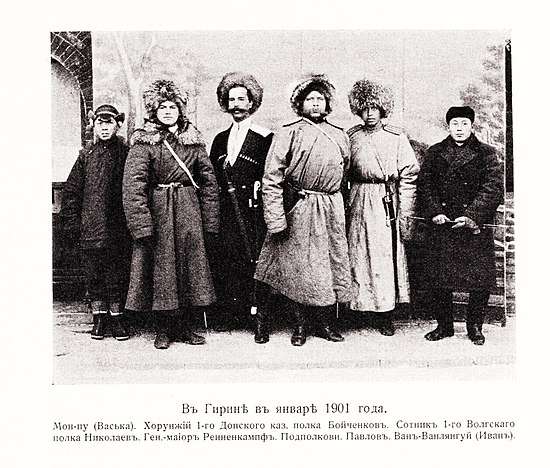

Rennenkampf participated in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China from 1900-1901. He distinguished himself with extreme success during the campaign and for military distinction, he was awarded both the 4th and 3rd classes[10][11] of the Order of St. George.

He acquired a name and wide popularity in military circles during the Chinese campaign (1900), for which he received two St. George crosses. The military, in general, were skeptical of the "heroes" of the Chinese war, considering it "not real." But the cavalry raid of Rennenkampf, in its daring and courage, deserved universal recognition.

It began in late July 1900, after the occupation of Aigun (near Blagoveshchensk). Rennenkampff, with a small detachment of three arms, defeated the Chinese in a strong position along the ridge of the Small Hingan and, having overtaken his infantry, with fourteen hundred Cossacks and a battery, having made 400 kilometers in three weeks with continuous skirmishes, captured a large Manchurian city of Qiqihar with a sudden raid. From here the high command assumed a systematic offensive against Jirin, gathering large forces in the 3 regiments of infantry, 6 regiments of cavalry and 64 guns, under the command of the famous general Kaulbars ... But, without waiting for the detachment to be collected, gene. Rennenkampff, taking with him 10 hundred Cossacks and a battery, on August 24 moved forward along the Sungari valley; On the 29th he captured Boduna, where 1,500 boxers surrendered unawares to him without a fight; September 8, seized Kaun-Zheng-tzu, leaving here five hundred and a battery to ensure its rear, with the remaining 5-hundred, having done 130 km per day, flew to Jilin. This match, unparalleled in its speed and suddenness, caused the Chinese, exaggerating to the extreme the strength of Rennenkampff, the impression that Kirin, the second most populated city and the most important city of Manchuria, surrendered, and the big garrison folded it. A handful of Rennenkampff Cossacks, lost among the mass of the Chinese, for several days, until reinforcements arrived, was in a preoriginal position ... - Anton Denikin[12]

In mid September, Rennenkampf left for Dagushan, leaving hundreds of troops to protect the mint and arsenal. After several days of resetting, he, with his detachment attacked and occupied Tieling and Mukden, which he occupied until October. During the occupation, the general had faced numerous assassinations, during one encounter, when he and his troops entered a manor, three Chinese men with spear charged towards the general, but he was saved by a Cossack named Fyodor Antipyev, getting stabbed upon himself. For military distinction, he was awarded the Order of St. George of the 3rd degree.

In the war, the raid of the cavalry detachment of General von Rennenkampf was one of the most successful and decisive military operation in the Boxer Rebellion. In three months of continuous movement, the Russians took over 2,500 kilometres of land, most of the Chinese troops at Heilongjiang were pushed back and the rebel detachment were dispersed, leading to the cessation of the organised resistant movement of the Chinese.

Russo-Japanese War

In February 1904, after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Rennenkampf was appointed commander of the Trans-Baikal Cossack Division.[13]. In June, he was promoted to lieutenant-general for military distinction.

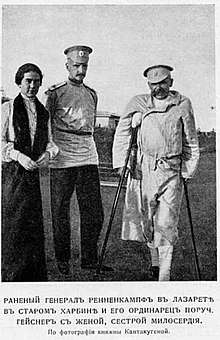

In late June 1904, during the scouting of the position of the Japanese at Liaoyang, he was shot in the leg and the shin of left leg was shattered. After less than two months or so, he returned to active service, without fully recovering his leg. In the Battle of Mukden, Rennenkampf distinguished himself again as during the battle, he commanded the Tsinghechensky detachment, which was at the left bank of the 1st Manchurian Army, during the battle, he showed great persistence, which combined with other reinforcements, was able to repulse Field Marshal Kawmura's offensive.

According to some historians and writers, after the Battle of Mukden, a personal conflict occurred between Rennenkampf and General Samsonov, and it came to an exchange of blows, which made the two of them lifelong foes. While some other historians argue that there could be no clashes between the generals. The main source of this rumor is the memoirs of the German general Max Hoffmann, who was a military agent in the Japanese army during the War and therefore incapable of personally observing relations among Russian generals and would subsequently become one of Rennenkampf’s enemy in the Battle of Tannenberg. In Hoffmann's memoirs, referring again to rumors, mentions that both generals quarrelled in Liaoyang after the battle, which was physically impossible, since at this time Rennenkampf was seriously injured.

After the war he commanded numerous army corps, including the 7th Siberian Army Corps, the 3rd Siberian Army Corps and Army Corps.

"Chita Republic"

After the war, he commanded an infantry battalion with several machine gun, which followed a train in Harbin, restoring the communication of the Manchurian Army from Western Siberia, but they were interrupted by a revolutionary movement in Eastern Siberia, the Chita Republic. Rennenkampf and his forces suppressed the movement and restored order in Chita.

However, after this successful campaign, he became the target of the rebels and there were several plots to assassinate him. In late October 1906, he faced an assassination attempt, while walking along the street with two of his adjutants, at that time, a SR member who was sitting on a bench, threw a bomb on to the general's feet, but the bomb only worked partially, instead of blowing Rennenkampf and his adjutants to shreds, the explosion only stunned them, and the rebel was later arrested and tried.

The decisive actions of Rennenkampf in the course of a war and decisive action in suppressing rebels led to further advancement in the general’s career. And in late December 1910, he was promoted to General of the Cavalry, and in 1912, General-Adjutant and the commander-in-chief of all the troops of the Vilna Military District in mid January 1913.

During this times, Rennenkampf wrote a book called The Twenty-Day Battle of my Detachment at the Battle of Mukden (German: Der zwanzigtägige Kampf meines Detachements in der Schlacht von Mukden), the book was then published in Berlin in 1909.

World War I

In the beginning of the First World War, Rennenkampf was appointed commander of the troops of the 1st Army of the Northwestern Front under commander-in-chief General Yakov Zhilinsky, together with his rival Samsonov, who was the commander of the 2nd Army, which was invading East Prussia from the south. In mid August 1914, he and his troops entered East Prussia from the east and defeated the 8th Army under the command of General Maximilian von Prittwitz at the Battle of Gumbinnen. But, later due to an incorrect assessment by Zhilinsky, the victory at Gumbinnen did not develop. After the battle, Rennenkampf was ordered by Zhilinsky to launch an offensive against the heart of East Prussia, Königsberg, but his army had not linked up with Samsonov’s 2nd Army due to a mistake made by Zhilinsky. As a result, the German 8th Army under the new commander, General (later field marshal) Paul von Hindenburg, charged through the gap, encircled and nearly wiped out the 2nd Army near Allenstein (the Battle of Tannenberg). When the desperate Samsonov sent his appeals for help, and instead of immediately replying and head south to aid Samsonov, Rennenkampf almost completely ignored the appeal, and when he finally began to head south, he and his men were a lot slower than it should and it was already too late (probably because of the personal rivalry between the two men). This remained one of the main reasons for the defeat of the 2nd Army at the battle. After the battle, Samsonov, fearing to hold responsibility for the defeat, committed suicide.

After the 2nd Army’s annihilation near Allenstein, Rennenkampf’s army took over all the defenses along the Deyma, Lava and the Masurian Lake. On 7 September, the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes began, as the Germans attacked the left flank of the 1st Army with a powerful detachment, and Zhilinsky, promised that he would provide Rennenkampf with reinforcements from other formations, did not do so. As a result, the 1st Army had to retreat in a hurry. The 2nd Army Corps led by General Vladimir Slyusarenko resisted desperately, so did Rennenkampf himself, who brought all the cavalrymen, reserves, and troops, all transferred from the right to left flank of the 20th Army Corps, in order to avoid encirclement by the Germans. And by 15 September, he skillfully helped his men escaped encirclement and withdrew behind the Neman, saving all the remanding troops he had. After this failure, Zhilinsky, despite his effort to blamed the defeat on Rennenkampf, was dismissed and was replaced by the General Nikolai Ruzsky from the Austrian Campaign.

In mid November at Łódź, due to the indecisiveness and the mistakes made by Ruzsky, the 1st Army failed to prevent General Reinhold von Schaeffer-Boyadel’s army from bursting out of the encircling movement, causing the front to retreat. A sharp conflict then broke out out between the two men. After that, he was dismissed from the office, and was then placed at the disposal of the Minister of War. His acts during the battle became subject of a special commission under General Peter von Baranoff, he was even tried for treason (due to his ethnic background). He was then dismissed in early October 1915 "for domestic reasons with a uniform and pension." After that, he stayed in Petrograd, living in retirement with his wife Vera until the Bolshevik coup. However his retirement life was extremely unsettling though, as he was falsely accused of betrayal, and all across Russia on all the streets and public places, people insulted him of his action. Even his fellow Baltic Germans accused him, on Vera’s recall, the Baltic Germans considered him "too Russian patriot" and "terrible Russophile". All this events rendered Rennenkampf into deep moral suffering.[14]

Here was part of a letter from the army chief of staff General Nikolai Yanushkevich to the Minister of War General Sukhomlinov about the issue of German General in the Russian Army:

The mass of complaints, libel, and so on, that the Germans (Rennenkampf, Scheidemann, Sievers, Eberhardt, etc.) are traitors and that the Germans are being given a move, as well as the mood of military censorship letters convinced that the appointment of P. AP (Plehve), with some of his regime and perseverance to carry out operations even with victims, prompted. (Grand Duke Nikolai) to abandon the original idea of PA (Plehve) and to dwell on a man with a Russian surname.

But in a further investigation, it revealed that it was Ruzsky’s strategic mistakes which let General Scheffer-Boyadel (de) and his troops get out of the encirclement. However, this did not return Rennenkampf back to service.

February Revolution

Rennenkampf was arrested shortly after the February Revolution, as many of the revolutionaries remembered his role in the suppression of the Chita Republic back in 1905. He was then questioned by the Extraordinary Investigative Commission of the Russian Republic, although he was not charged for anything.

October Revolution and death

Rennenkampf was arrested again after the Bolshevik Coup d'état, and like many other tsarist officials, was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress. But was released shortly afterwards, due to his health being deteriorating. After that, Rennenkampf, along with several other tsarist generals, went south to Taganrog, where his wife was native to, living under the guise of a merchant named Smokovnikov. After the Red Army took over the city, Rennenkampf disappeared under the Greek subject Mandusakis, but was tracked down by the Reds and was identified, after which he was brought to the headquarters of the Bolsheviks under the order of Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, the commander-in-chief of the Red Army in the area. After arriving, the former general was offered a command in the Red Army, and it should always be note that refusing meant death. Rennenkampf, at which point his life was threatened, still refused the offer, refusing to betrayed his fatherland, he said:

I'm old. I have not much left to live, for the salvation of my life, I will not become a traitor and will not go against my own. Give me an army well-armed, and I will go against the Germans, but you have no army; to lead this army would mean leading people to slaughter, I will not take this responsibility on myself.[15]

At the same time, the Germans were on the advance toward Taganrog, as well as the Czech and the Whites. As a result, he was taken hostage and brought near the railway tracks running from the Martsevo station to the Baltic Plant. After that, Rennenkampff was forced to dig his own grave, stripped naked with only his underwear on, stabbed in the eyes before ultimately getting shot with a bullet to the temple.

Aftermath

After his death, the Whites were told that Rennenkampf was on the way to Moscow. In May 1918, after the Whites had taken over Taganrog, a stick was found stuck into the ground near to the railway tracks running from the Martsevo station to the Baltic Plant. After they dug out the grave, they found several bodies including one nearly naked with a bullet shot to the head. When they took the corpses to a local cemetery (now the Taganrog Old Cemetery) in the city, Rennenkampf's wife Vera arrived at the cemetery and identified the nearly naked corpse was, in fact, her husband Paul. After which a funeral was held in which the White troops and his wife fulfilled his wish of being buried in an unmarked mass grave with other victims of the Red Terror. In recent years, after researches and efforts of local ethnographers, the resting place of Rennenkampf was established on the burial ground in the Old Cemetery in Taganrog.

Legacy

Before his execution, Rennenkampf had asked his wife Vera to make every effort to "whitewash his name from slander." It was not only Vera who considered her husband to be innocent of the strategic mistakes that led to the Russian defeats in the East Prussian campaign. This view of the impeccability of Rennenkampf's acts in the campaign adhered to a significant part of the White émigré: the generals: Baron Pyotr Wrangel, Anton Denikin, Nikolai Golovin and many others. In order to rehabilitate the general and in an effort to "give the light to the real face of General Paul Georg Edler von Rennenkampff," on the initiative of his wife in November 1936, the historical society of the "Friends of Rennenkampf" ("Les Amis de Rennenkampf") was founded in Paris. The honorary chairman was Vera herself, the president of the bureau was the husband of Rennenkampf's daughter Tatyana. The honorary committee included the widow of Baron Wrangel - Baroness Olga Mikhailovich, generals Nikolai Epanchin, Sergei Belosselsky-Belozersky, the commandant of the House of the Disabled, the municipal councilor of Paris E. Fore and others.

In the 2005 Russian film The Fall of the Empire, Rennenkampf was portrayed by Russian actor Sergei Nikonenko. In recent years, a plaque was erected in Taganrog in memories of the late general.[16]

Personal Collection

A collection of Chinese art piece looted by Rennenkampf during the Chinese Campaign during 1900 was now in display in the Alferaki Palace in his resting place in Taganrog.

Family

Being born into a huge and wealthy family, Rennenkampf had a rather large family in general, having 5 brothers and 2 sisters:[17][18][19]

- Jakob Edler von Rennenkampff (1843-1921)

- Elizabeth Ingeborg Helene Edle von Rennenkampff (1844-1915)

- Axel Julius Edler von Rennenkampff (1846-1853)

- Gustav Georg Edler von Rennenkampff (1848-1853)

- Woldemar Konstantin Edler von Rennenkampff (1852-1912)

- Olga Natalia Edle von Rennenkampff (1856-1919)

- Georg Olaf Edler von Rennenkampff (1859-1915)

Rennenkampf himself married the total of 4 times. In 1882, he married to Baltic German noblewoman Adelaida Franziska von Thalberg, they had 4 children together: Adelaida Ingeborg (1883-1896), Woldemar Konstantin (1884), Iraida Hermaine (1885-1950), and Margarethe Tamara (1888-1889). But only one out of 4 children survived into adulthood. Thalberg died after just only 6 years of marriage, after which Rennenkampf married 3 more women. In 1890 in Vilno, Rennenkampff married Lydia Kopylova, which he had one more children with, Anna Lydia[20] (1891-1937). He then married to Evgenia Dmitryevich Grechov, whom he had no children with. And finally in 1907 in Irkutsk, he married Vera Nikolayevich Krasan (Leonutova), with whom he had a daughter with, Tatyana (1907-1994), and adopted Vera's daughter from her first marriage, Olga (1901-1918), but unlike other marriages, Rennenkampf's marriage with Vera was long and happy. Vera, as the wife of the commander of the Vilno Military District, was a trustee and member of a branch of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. When the war breakout, she regularly participated in organizations for the caring of the wounded. In Vera’s Memoirs, she also wrote her founding of the Committee for Assistance to the families of reserve lower ranks, the tailoring workshops for the front, how she participated in the formation of the flying car detachment of the Evangelical Red Cross that took the wounded from the battlefield. After the war and Rennenkampf’s death, the fate of the other family members were unknown, but Vera and Tatyana escaped abroad to Paris, France, and unfortunately for Olga, she was murdered at her doorsteps at the same month of her stepfather’s murder. The rest of the family either fled to the Baltics or Germany during the civil war.

Personality

I was not acquainted with Rennenkampf, but he turned out to be what I imagined him to be: a Russified German, a blond-haired man with huge arms and braces. A cold, steel look, like his whole appearance, gave him the appearance of a strong, strong-willed man. He spoke without any accent. Among the decrepit old men and effeminate Sybarites, who constituted the majority of the top command staff, Rennenkampf undoubtedly stood out for his health, a cheerful air. Undressing daily in the morning naked, in any combat situation, he poured buckets of cold water. -Count Aleksei Ignatiev[21]

Honours and awards

Russian Empire

Foreign

Reference

Citations

- ↑ "Американский след"..

- ↑ Установлено место захоронения генерала П.К. Ренненкампфа

- ↑ Regarding personal names: Edler is a rank of nobility, not a first or middle name. The female form is Edle.

- ↑ Klingspor, Carl Arvid. Baltic coat of arms book, pp. 90

- ↑ Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 2, 3: Estonia. Görlitz (1930), pp. 192

- ↑ Rennenkampff, v./ Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

- ↑ Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 2, 3: Estonia. Görlitz (1930), pp. 205

- ↑ Carl Adam Freiherr von Stackelberg/ Genealogy on the Internet by Stackelberg

- ↑ Carl Adam von Stackelberg: Stackelberg was descended from Karl Wilhelm, while Rennenkampff was descended from Adam Friedrich.

- ↑ Recipients of the Order of St. George, 4th degree

- ↑ Recipients of the Order of St George, 3rd dgree

- ↑ Denikin, Anton The path of the Russian officer. - M .: Sovremennik (1991)

- ↑ Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, pp. 315–17.

- ↑ Rennenkampf Pavel Karlovich: last paragraph of the passage

- ↑ Pavel Karlovich von Rennenkampf

- ↑ In Taganrog remembered the Bolsheviks tortured General Pavel Rennenkampf

- ↑ Paul Georg von Rennenkampff (1854-1918)

- ↑ Rennenkampff, Paul Georg Edler v./Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

- ↑ Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 2, 3: Estonia. Görlitz (1930), pp. 209

- ↑ Rennenkampff, Anna Lydia v./Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

- ↑ The life and death of the general

Further reading

- Connaughton, R.M (1988). The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear – A Military History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5, London, ISBN 0-415-00906-5.

- Jukes, Geoffrey. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War.

ISBN 0-8108-4927-5: The Scarecrow Press. templatestyles stripmarker in

|location=at position 1 (help) - Warner, Denis & Peggy. The Tide at Sunrise, A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. (1975). ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 2, 3: Estonia. Görlitz (1929): Rennenkampff

- Klingspor, Carl Arvid. Baltic heraldic coat of arms all, belonging to the knighthoods of Livonia, Estonia, Courland and Oesel noble families. Stockholm (1882)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pavel Rennenkampf. |

- biography at Russojapanesewar.com

- Who's Who: Paul von Rennenkampf

- To pay the debt of memory

- Rennenkampff, Paul Georg v./ Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Fyodor Martsov |

Commander of the Vilna Military District 20 January [O.S. 7] 1913 – 19 July [O.S. 6] 1914 |

Succeeded by Position abolished |

| Preceded by Field Marshal Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken (as the commander-in-chief of the army) |

Commander of the 1st Army 1 August [O.S. 18 July] 1914 – 30 November [O.S. 17] 1914 |

Succeeded by Alexander Litvinov |