Paul Langevin

| Paul Langevin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

23 January 1872 Paris, France |

| Died |

19 December 1946 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Residence | France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater |

University of Cambridge Collège de France University of Paris (Sorbonne) ESPCI |

| Known for |

Langevin equation Heisenberg–Langevin equations Langevin dynamics Langevin function Twin paradox |

| Awards |

Hughes Medal (1915) Copley Medal (1940) Fellow of the Royal Society[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions |

ESPCI École Normale Supérieure |

| Thesis | Research on ionized gases (1902) |

| Doctoral advisors |

Pierre Curie Joseph John Thomson Gabriel Lippmann |

| Doctoral students |

Irène Joliot-Curie Louis de Broglie Léon Brillouin |

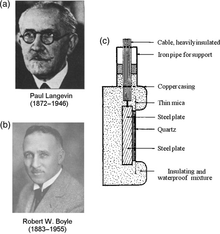

Paul Langevin ForMemRS[1] (/lænʒˈveɪn/;[2] French: [pɔl lɑ̃ʒvɛ̃]; 23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a prominent French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes, an antifascist organization created in the wake of the 6 February 1934 far right riots. Langevin was also president of the Human Rights League (LDH) from 1944 to 1946 – he had just recently joined the French Communist Party. Being a public opponent against fascism in the 1930s resulted in his arrest and consequently he was held under house arrest by the Vichy government for most of the war.

Previously a doctoral student of Pierre Curie and later a lover of Marie Curie, he is also famous for his two US patents with Constantin Chilowsky in 1916 and 1917 involving ultrasonic submarine detection.[3] He is entombed at the Panthéon.

Life

Langevin was born in Paris, and studied at the École de Physique et Chimie[4] and the École Normale Supérieure. He then went to Cambridge University and studied in the Cavendish Laboratory under Sir J. J. Thomson.[5] Langevin returned to the Sorbonne and obtained his Ph.D. from Pierre Curie in 1902. In 1904, he became professor of physics at the Collège de France. In 1926, he became director of the École de Physique et Chimie (later became École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la Ville de Paris, ESPCI ParisTech), where he had been educated. He was elected in 1934 to the Académie des sciences.

Langevin is noted for his work on paramagnetism and diamagnetism, and devised the modern interpretation of this phenomenon in terms of spins of electrons within atoms.[6] His most famous work was in the use of ultrasound using Pierre Curie's piezoelectric effect. During World War I, he began working on the use of these sounds to detect submarines through echo location.[3] However the war was over by the time it was operational. During his career, Paul Langevin also spread the theory of relativity in academic circles in France and created what is now called the twin paradox.[7][8]

He married Jeanne Desfosses in 1898, with whom he had four children: Jean, André, Madeleine and Hélène. In 1910, he reportedly had an affair with the then-widowed Marie Curie;[9][10][11][12] some decades later, their respective grandchildren, grandson Michel Langevin (the son of André Langevin and Luce Langevin-Dubus) and granddaughter Hélène Joliot (Hélène Langevin-Joliot, the daughter of Frederic Joliot and Irène Curie) got married to one another. He was also noted for being an outspoken opponent of Nazism, and was removed from his post by the Vichy government following the occupation of the country by Nazi Germany. He was later restored to his position in 1944. He died in Paris in 1946, two years after living to see the Liberation of Paris. He is buried near several other prominent French scientists in the Pantheon in Paris.

In 1933, he had a son, Paul-Gilbert Langevin, with physicist Eliane Montel (1898-1992). Paul-Gilbert became later a renowned musicologist.

His daughter, Hélène Solomon-Langevin, was arrested for Resistance activity and survived several concentration camps. She was on the same convoy of female political prisoners as Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier and Charlotte Delbo.

Submarine detection

In 1916 and 1917, Paul Langevin and Chilowsky filed two US patents disclosing the first ultrasonic submarine detector using an electrostatic method (singing condenser) for one patent and thin quartz crystals for the other. The amount of time taken by the signal to travel to the enemy submarine and echo back to the ship on which the device was mounted was used to calculate the distance under water.

In 1916, Lord Ernest Rutherford, working in the UK with his former McGill University PhD student Robert William Boyle, revealed that they were developing a quartz piezoelectric detector for submarine detection. Langevin's successful application of the use of piezoelectricity in the generation and detection of ultrasound waves was followed by further development.[13]

See also

- Born coordinates, for the Langevin observers in relativistic physics

- Langevin dynamics

- Langevin equation

- Langevin function

- Brillouin and Langevin functions

- Solvay Conference

- Brownian motion

- Paramagnetism

- Diamagnetism

- Twin paradox

- Special relativity

- Langevin (crater)

- Philippe Pinel

- Georges Politzer

- Jacques Solomon

- Hélène Langevin-Joliot

- Luce Langevin-Dubus

- Eliane Montel

- Paul-Gilbert Langevin

Bibliography

- The spirit of scientific teaching (1904)

- The Relations of physics of electrons to other branches of Science (1906)

- On the theory of brownian motion (1908)

- The evolution of space and time (1911)

- Time, space and causality in modern physics (1911)

- The relativity principle (1922)

- The general aspect of relativity theory (1922)

- The educative meaning of history of sciences (1926)

- Fascism and democracy (1926)

- The steps of scientific thought (1927)

- Social functions of scientific investigation (1928)

- New mechanics and chemistry (1928)

- Actual orientation of physics (1930)

- Einstein's works and astronomy (1931)

- Contribution of physical sciences to general culture (1931)

- Is there a determinism crisis? (1931)

- Science and secularism (1931)

- The problem of general culture (1932)

- Teaching in China (1933)

- The notion of corpuscle and atom (1933)

- The human value of science (1934)

- Statistics and determinism (1935)

- Space and time in an euclidean universe (1935)

- Pure science and technics (1936)

- Science and life (1937)

- Positivist and realistic currents in the philosophy of physics (1939)

- Modern physics and determinism (1939)

- Science as a moral and social evolution factor (1939)

- Science and freedom (1939)

- Culture and humanities (1944)

- The transmutations era (1945)

- Mecanist materialism and dialectic materialism (1945)

- Science and Peace (1946)

References

- 1 2 Joliot, F. (1951). "Paul Langevin. 1872–1946". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 7 (20): 405–426. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1951.0009. JSTOR 769027.

- ↑ "Langevin": entry in the American Heritage Science Dictionary, 2002.

- 1 2 Manbachi, A.; Cobbold, R. S. C. (2011). "Development and application of piezoelectric materials for ultrasound generation and detection". Ultrasound. 19 (4): 187. doi:10.1258/ult.2011.011027.

- ↑ ESPCI ParisTech Alumni 1891. espci.org

- ↑ He may not have been formally entered as a member of the university, as he is not found in John Venn's Alumni Cantabrigienses

- ↑ Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (2001). The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 423. ISBN 9780387951751.

- ↑ Paty, Michel (2012). "Relativity in France". In Glick, T. F. The Comparative Reception of Relativity. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 113–168. ISBN 9789400938755. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Langevin, P. (1911), "The Evolution of Space and Time", Scientia, X: 31–54 (translated by J. B. Sykes, 1973 from the original French: "L'évolution de l'espace et du temps").

- ↑ Robert Reid (1978) [1974] Marie Curie, pp. 44, 90.

- ↑ Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor (2009) Naming Infinity. Belknap Press. ISBN 0674032934. p. 43.

- ↑ Françoise Giroud (Davis, Lydia trans.), Marie Curie: A life, Holmes and Meier, 1986, ISBN 0-8419-0977-6.

- ↑ Susan Quinn (1995) Marie Curie: A Life, Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-60503-4.

- ↑ Arshadi, R.; Cobbold, R. S. C. (2007). "A pioneer in the development of modern ultrasound: Robert William Boyle (1883–1955)". Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 33: 3. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.030.

Sources

- Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, Isaac Asimov, Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1972, ISBN 0-385-17771-2.

- References to the affair with Marie Curie is found in Françoise Giroud (Davis, Lydia trans.), Marie Curie: A life, Holmes and Meier, 1986, ISBN 0-8419-0977-6, and in Susan Quinn, Marie Curie: A Life, Heinemann, 1995, ISBN 0-434-60503-4.

- Wolfram research biographical entry by Michel Barran.

- Annotated bibliography for Niels Bohr from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Further reading

- Luis Navarro, Josep Olivella, Langevin and the theory of magnetism, Épistémologiques, 2002

- Denis Brian, The Curies, a Biography of the Most Controversial Family in Science, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (UK) 2005.

- Julien Bok and Catherine Kounelis (2007). "Paul Langevin (1872–1946) – From Montmartre to the Panthéon: The Paris journey of an exceptional physicist" (PDF). Europhysics News. 38 (1).

- Adrienne R. Weill-Brunschvicg. "Langevin, Paul - Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, 2008".

External links

- Les bâtisseurs du monde:Langevin, on Ina.fr (in French)

- A la Sorbonne, le Front national universitaire fête le 73ème anniversaire de Paul Langevin, on Ina.fr (in French)