Paul Cuffee

For the Episcopalian Reverend missionary, see Paul Cuffee (1754-1812).

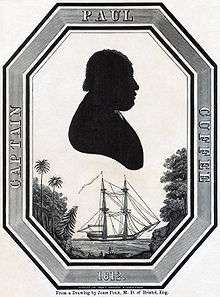

| Paul Cuffee | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Paul Cuffee by Chester Harding | |

| Born |

January 17, 1759 Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

September 7, 1817 (aged 58) Westport, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | sea captain |

Paul Cuffee or Paul Cuffe (January 17, 1759 – September 7, 1817) was an American Quaker businessman, sea captain, and abolitionist. His mother was Aquinnah Wampanoag and his father Ashanti, captured as a child and sold into slavery. In the mid-1740s he was freed by his Quaker master in Massachusetts.

After Cuffee's father died when the boy was 13 he and a brother worked to support their mother and three younger sisters. Cuffee eventually built a lucrative shipping empire in New England, trading primarily with Great Britain. He established the first racially integrated school in Westport, Massachusetts.[1]

A devout Christian, Cuffee often preached and spoke at the Sunday services at the multi-racial Society of Friends meeting house in Westport.[2] In 1813, he donated most of the money to build a new meeting house. He became involved in the British effort to develop the colony of Freetown, later Sierra Leone. Many Black Loyalists had been granted land by the Crown in Nova Scotia after the American Revolution. Cuffee helped those who wanted to leave to sail to the fledgling colony of Sierra Leone. He also helped support The Friendly Society of Sierra Leone, which provided financial support for the colony.

Early life

Paul Cuffee was born on January 17, 1759, on Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts. (This was during the French and Indian War). He was the youngest son of Kofi, known as Cuffee Slocum since being freed, and his wife Ruth Moses. Kofi was a member of the Ashanti, from the Ashanti Region of present-day southern Ghana.[3] He had been captured at age ten and brought as a slave to the English colony of Massachusetts. His Quaker owner, John Slocum, finally could not reconcile slave ownership with his religious values and gave Kofi his freedom in the mid-1740s. Kofi took the name Cuffee Slocum. In 1746, he married Ruth Moses.[4] Ruth was a member of the Wampanoag Nation on Martha's Vineyard. Cuffee Slocum worked as a skilled carpenter, farmer and fisherman, and taught himself to read and write. He worked diligently in order to buy a home, and in 1766 bought a 116-acre (0.47 km2) farm in nearby Dartmouth, Massachusetts.[2] The couple raised ten children together, of whom Paul was the seventh in line.[5]

During Paul's infancy there was no Quaker meeting house on Cuttyhunk Island, so his father taught himself the Scriptures and also taught his children.[6] In 1766, when Paul was seven, the family moved to the farm in Dartmouth. Cuffee Slocum died in 1772, when Paul was 13. As Paul's two eldest brothers by then had families of their own elsewhere, he and his brother John took over their father's farm operations, supporting their mother and three younger sisters. Around 1778, when he was 19, Paul persuaded his brothers and sisters to use their father's anglicized first name, Cuffee, as their family name, and all but the youngest did.[7] Paul, though, signed his name by spelling it 'Cuffe' with one 'e'.[8] His mother, Ruth Moses, died on January 6, 1787 soon after the end of the Revolutionary War.[9]

Paul Cuffee: marineer

At the time of his father's death, young Paul knew little more than the alphabet but dreamed of gaining an education and being involved in the shipping industry. The closest mainland port to Cuttyhunk was New Bedford, Massachusetts—the center of the American whaling industry. Cuffe used his limited free time to learn more about ships and sailing from sailors he encountered. Finally, at the age of 16, Cuffe signed onto a whaling ship and, later on, to cargo ships, where he learned navigation. In his journal, he referred to himself as a marineer. In 1776 during the American Revolution, he was captured and held prisoner by the British for three months in New York.[11] His descendants are eligible by his sacrifice for membership in the Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution, lineage societies founded in the late 19th century.

After his release, Cuffee returned to his siblings in Massachusetts, where he farmed and studied. In 1779, he and his brother David built a small boat to ply the nearby coast and islands.[12] Although his brother was afraid to sail in dangerous seas, Cuffe went out alone in 1779 to deliver cargo to Nantucket. He was waylaid by pirates on this and several subsequent voyages. Finally, he made a trip to Nantucket that turned a profit.[13]

At the age of 21, Cuffe refused to pay taxes because free blacks did not have the right to vote in Massachusetts. In 1780, he petitioned the council of Bristol County, Massachusetts to end such taxation without representation, which had been an issue leading to the Revolution. The petition was denied, but his suit contributed to the state legislature in 1783 granting voting rights to all free male citizens of the state.[14]

Cuffe finally made enough money to purchase another ship and hired crew for it. He gradually built up capital and expanded his ownership to a fleet of ships. After using open boats, he commissioned the 14- or 15-ton closed-deck ship Box Iron, and then an 18- to 20-ton schooner. He eventually operated his own shipyard where some of his ships were constructed.

Marriage and family

On February 25, 1783, Cuffe married Alice Pequit. Like Cuffe's mother, Pequit was a Wampanoag woman.[15] The couple settled in Westport, Massachusetts, where they raised their seven children: Naomi (born 1783), Mary (born 1785), Ruth (1788), Alice (1790), Paul Jr. (1792-1843), Rhoda (1795), and William (1799).[15]

Shipping

In the late 1780s Cuffe's flagship was the 25-ton schooner Sun Fish; his next purchase was the 40-ton schooner Mary. In 1795, he sold the Mary and Sun Fish to finance construction of the Ranger - a 69-ton schooner launched in 1796 from Cuffe's shipyard in Westport.[16] Wanting a larger homestead, in February 1799 he paid $3,500 for 140 acres (0.57 km2) of waterfront property in Westport.[17]

By 1800 he had enough capital to purchase a half-interest in the 162-ton barque Hero. By the first years of the nineteenth century, Cuffe was one of the most wealthy - if not the most wealthy - African Americans and Native Americans in the United States.[18] His largest ship, the 268-ton Alpha, was built in 1806, along with his favorite ship, the 109-ton brig Traveller.[19] In 1811 when Cuffe took the Traveller into Liverpool, The Times of London reported that it was likely the first vessel to reach Europe that was "entirely owned and navigated by Negroes."[20]

First venture into Sierra Leone

In the early nineteenth century, most Englishmen and Anglo-Americans believed that people of African descent were inferior to Europeans, even in New England, where residents were predominantly Congregational, Quaker, Methodist and Baptist. The Second Great Awakening, carried primarily by Quakers, Methodists and Baptists from New England to the South, had stimulated some owners to free their slaves after the American Revolutionary War. As slavery continued after the Revolution, primarily in the South, prominent men such as Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison believed the emigration of free Blacks to colonies outside the United States was the easiest and most realistic solution to the race problem in America. It was a means of providing an alternative for free blacks, rather than absorbing a large population of slaves by emancipation.[21]

Attempts by Europeans and Americans to colonize Blacks in other parts of the world had failed, including the British attempt to colonize Sierra Leone. Beginning in 1787, the Sierra Leone Company sponsored 400 people, mostly known as the Black Poor of London, to resettle in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Many were African Americans who had been freed from slavery by joining British lines during the Revolution. They had been resettled in London and Nova Scotia. Freetown struggled to establish a working economy and develop a government that could survive against outside pressures. After the financial collapse of the Sierra Leone Company, a second group, the newly created African Institution, offered migration to a larger group of Black Loyalists who had been resettled in Nova Scotia and London after the American Revolution. The African Institution's London sponsors hoped to gain an economic return while fostering the "civilizing" trades of educated Blacks in Africa.[22]

Although colonizing Sierra Leone was difficult, Cuffe believed it was a viable option for Blacks, and threw his support behind the movement. He wrote,

I have for these many years past felt a lively interest in their behalf, wishing that the inhabitants of the colony might become established in truth, and thereby be instrumental in its promotion amongst our African brethren.[23]

From March 1807 on, Cuffe was encouraged by members of the African Institution in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York City to help the fledgling efforts to improve Sierra Leone. Cuffe mulled over the logistics and chances of success for the movement before deciding in 1809 to join the project. On December 27, 1810, he left Philadelphia on his first expedition to Sierra Leone.[24]

Cuffe reached Freetown, Sierra Leone on March 1, 1811. He traveled the area investigating the social and economic conditions of the region. He met with some of the colony's officials, who opposed his idea for colonization of Blacks from the United States for fear of competition from American merchants.[25] Furthermore, his attempts to sell goods yielded poor results because of tariff charges resulting from the British mercantile system. On Sunday, April 7, 1811 Cuffe met with the foremost Black entrepreneurs of the colony. They penned a petition for the African Institution, stating that the colony's greatest needs were for settlers to work in agriculture, merchanting and the whaling industry, that these three areas would best facilitate growth for the colony. Upon receiving this petition, the members of the institution agreed with their findings.[26] Cuffe and the black entrepreneurs together founded the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone as a mutual-aid merchant group dedicated to furthering prosperity and industry among the free peoples in the colony and loosening the stranglehold that the English merchants held on trade.[27]

Cuffe sailed to Great Britain to secure further aid for the colony, arriving in Liverpool in July 1811. He met with the heads of the African Institution in London who raised some money for the Friendly Society. He was granted governmental permission and license to continue his mission in Sierra Leone.[28] Encouraged by this support, Cuffe returned to Sierra Leone, where he and local merchants solidified the role of the Friendly Society. They refined development plans for the colony by building a grist mill, saw mill, rice-processing factory, and salt works.[29]

Embargo, the President, and the War of 1812

Relations between the United States and Great Britain were strained and, as 1811 ended, the U.S. established an embargo on British goods. This affected trans-Atlantic trade, as well as trade with Canada. When Cuffe reached Newport, Rhode Island in April 1812, his ship the Traveller was seized by U.S. customs agents, along with all its goods. Officials would not release his cargo, so Cuffe went to Washington, D.C. to appeal.[30] He met with Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin and President James Madison. Madison warmly welcomed Cuffe into the White House. Deciding that Cuffe had not intentionally violated the embargo, Madison ordered his cargo returned to him.

Madison also questioned Cuffe about his time in Sierra Leone and conditions there. Eager to learn about Africa, Madison was interested in the possibility of expanding recolonization by American free blacks. But Madison eventually rejected Cuffe's plans, since Sierra Leone was a British colony. The strained diplomatic situation with Britain broke out in the War of 1812. Despite this, Madison regarded Cuffe as the US authority on Africa.[31]

Cuffe intended to return to Sierra Leone regularly, but in June the war started. As a pacifist Quaker, Cuffee opposed the war on spiritual grounds. He also despaired of the interruption of trade and efforts to improve Sierra Leone.[32] As the war between the U.S. and Britain continued, Cuffe tried to convince both countries to ease their restrictions on trading, but was unsuccessful. Like other merchants, he was forced to wait until the war ended.[33]

Meanwhile, Cuffe visited Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, speaking to groups of free Blacks about the colony. Cuffe also urged Blacks to form organizations in these cities, communicate with each other, and correspond with the African Institution and with the Friendly Society at Sierra Leone. He printed a pamphlet about Sierra Leone to inform the general public of his ideas.[34] In the summer of 1813 Cuffee donated money as the largest contributor to rebuilding the Westport Friends' Meeting House.[32]

The war caused Cuffe to lose ships and his business suffered financially. The Hero was declared unseaworthy while in Chile and never returned. John James of Philadelphia, his partner in the Alpha, ran that ship unprofitably.[35] Fortunately the war ended with the Treaty of Ghent at the end of 1814. After getting his finances in order, Cuffee prepared to return to Sierra Leone.

After the war

Cuffe sailed out of Westport on December 10, 1815, with 38 African-American colonists (18 adults and 20 children[36] ranging in age from eight months to 60 years.[37]) The group included William Gwinn and his family from Boston.[38]

The expedition cost Cuffe more than $4000. Passengers paying their own fares, plus a donation by William Rotch of New Bedford, Massachusetts, accounted for the remaining $1000 in expenses.[39] The colonists arrived in Sierra Leone on February 3, 1816. The ship was carrying such supplies as axes, hoes, a plow, a wagon, and parts to make a saw mill. Cuffe and his immigrants were not greeted as warmly as before. Governor MacCarthy was already having trouble keeping the general population in order and was not excited at the idea of more immigrants. In addition, the Militia Act, which had been imposed upon the colony, required all adult males to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Many local people refused to do so for fear of being drafted into military service.[40]

Although things did not go exactly as Cuffee had planned economically - his cargo sold at undervalued prices[41] - the new colonists were finally settled in Freetown. Cuffe believed that once continuous trade between the United States, Britain, and Africa commenced, the society would be able to realize his predicted success.[42] For Cuffe, though, the expedition was costly. Each colonist needed a year's provisions to get started, which he had advanced for them. Governor MacCarthy was sure that the African Institution would reimburse Cuffe, but the American suffered more than $8,000 in deficit after having to pay high tariff duties as well.[43] The African Institution in England never contributed to the mission at all, and Cuffe had to deal with hard economic consequences.[44] He knew he needed stronger financial backing before undertaking another such expedition.

Later years

On his return to New York in 1816, Cuffe exhibited to the New York chapter of the African Institution the certificates of the landing of those colonists at Sierra Leone. "He has also received from Gov. M'Carthy a certificate of the steady and sober conduct of the settlers since their arrival, and an acknowledgment of $439.62, humanely advanced to them since they landed, to promote their comfort and advantage."[45]

In 1816, Cuffe envisioned a mass emigration plan for African Americans, both to Sierra Leone and possibly to Haiti, the former French colony of Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean that had gained independence in 1804.[46] Congress rejected his petition to fund a return to Sierra Leone. During this time period, many African Americans began to demonstrate interest in emigrating to Africa, and some people believed this was the best solution to problems of racial tensions in American society. Cuffe was persuaded by Reverends Samuel J. Mills and Robert Finley to help them with the plans of the American Colonization Society (ACS), formed for this purpose. Cuffe was alarmed at the overt racism of many members of the ACS, who included slaveholders. Certain co-founders, particularly Henry Clay, advocated relocating freed Negroes as a way of ridding the South of potentially "troublesome" agitators who might threaten the slave societies of the plantation system.[47] Other Americans who became active preferred to encourage emigration to Haiti. the government of President Jean-Pierre Boyer encouraged American immigrants, believing they could help develop the country and might help gain formal recognition by the US government of his republic.

Death and legacy

In early 1817, Cuffe's health deteriorated. He never returned to Africa. He died on September 7, 1817. His final words were "Let me pass quietly away." Cuffe left an estate with an estimated value of almost $20,000.[48] His will bequeathed money to his widow, siblings, children, grandchildren, and the Friends Meeting House in Westport.[49] He is buried in the graveyard of the Westport Friends Meetinghouse.

His relatives and descendants intermarried with other black families in the shipping industry. His sister Mary Cuffee had married Micah Quaben Wainer. Their sons Paul, Michael, Thomas and Jeremiah had accompanied their uncle Paul Sr. on voyages, and bought or inherited interest in Paul Sr.'s ships. Paul Jr. had married Polly Cook in 1812, who was the sister of a black seaman. Alice Cuffee married Polly's brother, Captain Pardon Cook, in 1820. . Paul Sr.'s youngest son, William, became a skilled seaman in his own right, captaining the Rising States. He and three other men died on board in November–December 1837 during an accident in the midst of rough weather en route to Cape Verde.

Legacy and honors

- On January 16, 2009, Congressman Barney Frank inserted extended remarks titled "Paul Cuffe: Voting Rights Pioneer" into the Congressional Record.[50]

- Governor Deval Patrick of Massachusetts issued a proclamation honoring the 200th birthday of Paul Cuffe.[51]

- On January 17, 2009, the 258th anniversary of Cuffe's birth, Governor Charlie Baker of Massachusetts issued a proclamation honoring the 200th anniversary of Paul Cuffe's death (September 7, 2017).[51]

See also

References

- ↑ Cuffe, Paul & Rosalind Cobb Wiggins (1996). Captain Paul Cuffe's Logs and Letters, 1808-1817: A Black Quaker's "Voice from Within the Veil". Howard University Press. ISBN 088258183X.

- 1 2 Abigail Mott, Biographical sketches and interesting anecdotes of persons of colour (printed and sold by W. Alexander & Son; sold also by Harvey and Darton, W. Phillips, E. Fry, and W. Darton, London; R. Peart, Birmingham; D. F. Gardiner, Dublin, 1826), pp. 31–43 (accessed on Google Books).

- ↑ Wiggins, p. 45.

- ↑ Thomas, Lamont D. Paul Cuffe: Black Entrepreneur and Pan-Africanist (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), pp 4-5.

- ↑ Wiggins, pp. 47-8.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 5.

- ↑ Sherwood, Henry Noble, The Journal of Negro History, vol. 8, no. 2 (April 1923), p. 155.

- ↑ Wiggins, throughout

- ↑ Harris, Sheldon. Paul Cuffee: Black America and the African Return (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972), p. 17.

- ↑ Wiggins, Rosalind Cobb ed. Captain Paul Cuffe's Logs and Letters. Washington: Howard University Press, 1996. p.xi

- ↑ Harris, p. 18

- ↑ Harris, p. 19.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 9.

- ↑ Gross, David (ed.), We Won't Pay!: A Tax Resistance Reader, pp. 115-117, ISBN 1-4348-9825-3.

- 1 2 Harris, p. 30.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 16.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 18.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 22.

- ↑ Harris, p. 20.

- ↑ Quote: "The brig Traveller, lately arrived at Liverpool, from Sierra Leone, is perhaps the first vessel that ever reached Europe, entirely owned and navigated by Negroes. Her mate and all her crew are negroes, or the immediate descendants of negroes." The Times (London), 2 August 1811, p. 3

- ↑ Thomas, p. 74.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 32-33, 51.

- ↑ "A Gastronomic Tour through Black History/BHM 2012", Blog, 26 February 2012

- ↑ Thomas, p. 49.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 137, note 16, points out letters from Governor Columbine, and p. 58 further speaks to the tight hold the British merchant company Macauley & Babington held over the Sierra Leone trade to the detriment of native black merchants.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 80.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 53-54, and Harris p. 55.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 57-64.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 71.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Harris, pp. 58-60.

- 1 2 Thomas, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 84-90.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 77-81.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 94.

- ↑ Greene, Lorenzo Johnston. The Negro in Colonial New England (Studies in American Negro Life, New York: Atheneum, 1942), p. 307.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 100.

- ↑ James Oliver Horton; Lois E. Horton (5 December 1996). In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700-1860. Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-19-988079-9. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Sherwood, Henry Noble. "Paul Cuffe", The Journal of Negro History, VIII, vol. 8, no. 2 (April 1923), p. 198-9

- ↑ Thomas, p. 68.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 101-02.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 102.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 103.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 104.

- ↑ Providence Gazette, June 22, 1816.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 110.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 111.

- ↑ Channing, George A. Early Recollections of Newport, Rhode Island from the year 1793 to 1811, Boston: A. J. Ward and Charles E. Hammett, Jr., 1898. p. 170, Greene, p. 307, and Thomas, p. 118.

- ↑ Cuffe, Paul. "The Will of Paul Cuffe." The Journal of Negro History vol. 8, no. 2 (April 1923) pp. 230-232. ASALH website. Accessed on February 22, 2016 via JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2713613.pdf

- ↑

- 1 2 In the possession of Brock N. Cordeiro of Dartmouth, MA

Further reading

- Cordeiro, Brock N. Paul Cuffe: A Study of His Life and the Status of His Legacy in Old Dartmouth. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, 2004. “Paul Cuffe: A Study of His Life and the Status of His Legacy in Old Dartmouth”.

- Harris, Sheldon H. Paul Cuffee: Black America and the African Return. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972.

- The American Promise: A History of the United States, 1998 (p. 286).

- Nell, William C. The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, 1855.

- Thomas, Lamont D. Rise to Be a People, University of Illinois Press, 1986, republished in 1988 as Paul Cuffe: Black Entrepreneur and Pan-Africanist

- Wiggins, Rosalind Cobb ed. Captain Paul Cuffe's Logs and Letters. Washington: Howard University Press, 1996. https://sites.google.com/s/0B8c94YIiNSX-U0tsMzlUVTluR1U/p/0B8c94YIiNSX-aXlUWFhfRHRVcFE/edit?authuser=1

- Claus Bernet (2010). "Paul Cuffee". In Bautz, Traugott. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 31. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 303–308. ISBN 978-3-88309-544-8.

External links

- Paul Cuffee School in Providence, RI

- Works by Paul Cuffe at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Paul Cuffee at Internet Archive