Paternoster Row

Paternoster Row was a street in the City of London that is supposed to have received its name from the fact that, when the monks and clergy of St Paul's Cathedral would go in procession chanting the great litany, they would recite the Lord's Prayer (Pater Noster being its opening line in Latin) in the litany along this part of the route. The prayers said at these processions may have also given the names to nearby Ave Maria Lane and Amen Corner. An alternative etymology is the early traders who sold a type of prayer bead known as a "pater noster".

The area was a centre of the London publishing trade,[1][2] with booksellers operating from the street.[3] In 1819 Paternoster Row was described as "almost synonymous" with the book trade.[4]

A bust of Aldus Manutius, writer and publisher, above the fascia of number 13.[5] The bust was placed there in 1820 by Bible publisher Samuel Bagster.[6]

It was reported that Charlotte Bronte and Ann Bronte stayed at the Chapter Coffeehouse on the street when visiting London in 1847. They were in the city to meet their publisher regarding Jayne Eyre.[7]

A fire broke out at number 20 Paternoster Row on 6 February 1890. Occupied by music publisher Fredrick Pitman, the first floor was found to be on fire by a police officer at 21.30. The fire alarm at St. Martain's-le-Grand and fire crews extinguished the flames in half an hour. The floor was badly damaged, with smoke, heat and water impacting the rest of the building.[8]

This blaze was followed later the same year on 5 October by 'an alarming fire'. At 00.30 a fire was discovered at W. Hawtin and Sons, based in numbers 24 and 25. The wholesale stationers' warehouse was badly damaged by the blaze.[9]

On 21 November 1894 police raided an alleged gambling club which was based on the first floor of 59 Paternoster Row. The club know both as the 'City Billiard Club' and the 'Junior Gresham Club' had been there barely 3 weeks at the time of the raid. Forty-five arrests were made, including club owner Albert Cohen.[10]

On 4 November 1939 a large scale civil defence exercise was held in the City of London. One of the simulated seats of fire was in Paternoster Row.[11]

Trübner & Co. was one of the publishing companies on Paternoster Row. The street was devastated by aerial bombardment during the Blitz of World War II, suffering particularly heavy damage in the night raid of 29–30 December 1940, later characterised as the Second Great Fire of London, during which an estimated 5 million books were lost in the fires caused by tens of thousands of incendiary bombs.[12]

After the raid a letter was written to The Times describing 'a passage leading through "Simpkins" [which] has a mantle of stone which has survived the melancholy ruins around it. On this stone is the Latin inscription that seems to embody all that we are fighting for :- VERBUM DOMINI MANET IN AETERNUM' [The word of God remains forever].[13]

Another correspondent with the newspaper, Ernest W. Larby, described his experience of 25 years working on Paternoster Row -[14]

...had he [Lord Quickswood] worked for 25 years, as I did, in Paternoster Row, he would not have quite so much enthusiasm for those narrow ways into whose buildings the sun never penetrated... What these dirty, narrow ways of the greatest city in the world really stood for from the people's viewpoint are things we had better bury.

— Ernest W. Larby

The ruins of Paternoster Road were visited by Wendell Wilkie in January 1941. He said, "I thought that the burning of Paternoster Row, the street where the books are published, was rather symbolic. They [the Germans] have destroyed the place where the truth is told".[15]

In 2003 the street was replaced with Paternoster Square, the modern home of the London Stock Exchange, although a City of London Corporation road sign remains in the square near where Paternoster Row once stood.

Printers and booksellers based in Paternoster Row

Note: Before c. 1762 premises in London had signs rather than numbers.

- The Tyger's Head - Christopher and Robert Barker (1545-1629)[16]

- The Star - Henry Denham (1564)[17]

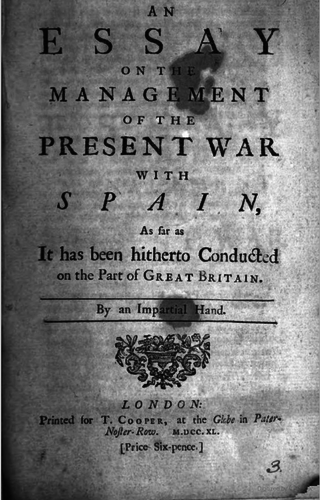

- The Globe – T. Cooper (1740)[18]

- The Ship (later 38-41) William Taylor (1719), before him J. Taylor (1710 -1719), his father, subsequently Longmans (see no 39).[19]

- The Black Swan William Taylor, before him possibly J. Taylor, his father, subsequently Longmans (see no 39).

- The Crown T Rickerton (1721)[20]

- No. 1 – J Van Voorst (1851)[21]

- No. 2 – Orr and Co. (1851),[21] J. W. Myers (~1800)[22]

- No. 3 – Jan Van Voorst (1838)[23]

- No. 9 – S. W. Partridge and Co. (1876) [24]

- No. 11 – W. Brittain (1840)[25]

- No. 12 – Trubner and Co (1856)[26]

- No. 15 – Samuel Bagster and Sons (1825)[27] (1851)[21] (1870)[28]

- No. 17 – Thomas Kelly (1840)[29]

- No. 20 & 21 – F. Pitman, later F. Pitman Hart and Co. Ltd. (1904) [30]

- No. 21 – J. Parsons, (1792)[31]

- No. 23 – Piper, Stephenson, and Spence (1857)[32]

- No. 24 – George Wightman (1831)[33]

- No. 27 – Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row – Walton and Maberly (also at 28 Upper Gower Street) (1837[34]-1857[32])

- No. 31 – Sheed & Ward

- No. 33 – Hamilton and Co. (1851)[21]

- No. 37 – James Duncan (1825–1838) ; Blackwood and Sons, (1851)[21]

- No. 39 – Longman, Hust, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green (1825),[27] later Longman and Co. (1851)[21] later Longmans, Green, and Co. (1902).[35]

- No. 40 – West and Hughes (~1800)[22]

- No. 47 – Chambers (1891), formerly occupied by Baldwin and Craddock[36]

- No. 56 – The Religious Tract Society (1851)[21]

- No. 60 – The Sunday School Union (1851)[21]

- No. 62 – Eliot Stock (1893)[37]

- No. 65 - Houlston and Stoneman

- Oxford University Press – Bible warehouse destroyed by fire in 1822,[38] rebuilt c. 1880.

- Sampson Low (after 1887)

- Thomas Nelson[39]

- Hawes, Clarke and Collins (1771) [40]

- H. Woodfall & Co.

- C Davis (1740)[41]

- Marshall Brothers Ltd., Keswick House, Paternoster Row, London

Others based in Paternoster Row

- No. 60 – Friendly Female Society, "for indigent widows and single women of good character, entirely under the management of ladies."[27]

In popular culture

- The Paternoster Gang are a trio of Victorian detectives aligned with the Doctor in the television series Doctor Who, so named because they are based in Paternoster Row.

- In the episode "Young England" of the 2016 television series Victoria, a stalker of Queen Victoria indicates that he lives on Paternoster Row. (Coincidentally, the actress playing Victoria in the series, Jenna Coleman, had appeared in several episodes of Doctor Who that featured the aforementioned Paternoster Gang.)

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paternoster Row. |

- ↑ "Districts – Streets – Paternoster Row". Victorian London. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ↑ James Raven. The business of books: booksellers and the English Book Trade. 2007

- ↑ "Paternoster Row". Old and New London: Volume 1. 1878. pp. 274–281.

- ↑ A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to London and Its Environs: With Two Large Section Plans of Central London... Ward, Lock & Company, Limited. 1819.

- ↑ "Aldus In The City". The Times (48522). 25 January 1940. p. 4.

- ↑ "Aldus in the City". The Times (48524). 27 January 1940. p. 4.

- ↑ "News in Brief - Charlotte Bronte in London". The Times (41152). 27 April 1916. p. 9.

- ↑ "Fire". The Times (32929). 7 February 1890. p. 7.

- ↑ "Paternoser-row, City". The Times (33135). 6 October 1890. p. 6.

- ↑ "Raid on City "Club"". The Times (34428). 22 November 1894. p. 11.

- ↑ ""Great Fire" Of London". The Times (48455). 6 November 1939. p. 3.

- ↑ "London Blitz — 29th December 1940 | Iconic Photos". Iconicphotos.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ↑ "Verbum Domini". The Times (48839). 1 February 1941. p. 5.

- ↑ "Sir,-It is with some diffidence that I com-". The Times (49395). 17 November 1942. p. 5.

- ↑ "Ministers Greet Mr. Willkie". The Times (48835). 28 January 1941. p. 4.

- ↑ A Dictionary of Printers and Printing.

- ↑ Notes and Queries.

- ↑ An Impartial Hand (1740). An Essay on the Management of the Present War with Spain. T. Cooper.

- ↑ Publication (1906). London Topographical Record. 3. London Topographical Society. p. 159.

- ↑ Notes and Queries.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The British Metropolis in 1851

- 1 2 Glasse, Hannah; Maria Wilson (1800). The Complete Confectioner; or, Housekeeper's Guide: To a simple and speedy method of understanding the whole ART OF CONFECTIONARY. London, United Kingdom: West and Hughes.

Printed by J. W. Myers, No. 2, Paternoster-row, London, for West and Hughes, No. 40, Paternoster-row.

- ↑ The Athenaeum: Journal of Literature, Science, the Fine Arts, Music and the Drama. 1838. p. 846.

- ↑ Church of England Temperance Tracts, no. 19, 1876

- ↑ The Secret History of the Court of England from the Commencement of 1750 to the Reign of William the Fourth. W. Brittain. 1840. p. frontispiece.

- ↑ The London catalogue of periodicals, newspapers and transactions of various societies with a list of metropolitan printing societies and clubs. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. 1856. p. 3, of wrapper.

- 1 2 3 John Feltham (1825). The picture of London, enlarged and improved (23rd ed.). Longman, Hust, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green. p. iv.

- ↑ Notes and Queries, 1870, p240

- ↑ Practical CARPENTRY, JOINERY and CABINET MAKING. Thomas Kelly. 1 July 1840.

- ↑ The World's Paper Trade Review, 13 May 1904, p. 38

- ↑ Plain truth : or, an impartial account of the proceedings at Paris during the last nine months. Containing, Among other interesting Anecdotes, a particular statement of the memorable tenth of August, and third of September. By an eye witness.. 1792.

- 1 2 The Examiner. John Hunt. 1857. p. 336.

- ↑ William Fox, Robert Raikes (1831). Memoir of W. Fox, Esq., founder of the Sunday-School Society: comprising the history of the origin ... of that ... institution, with correspondence ... between W. Fox, Esq. and R. Raikes, etc. Joseph Ivimey (editor). George Wightman.

- ↑ Augustus De Morgan (1837). Elements of algebra, preliminary to the differential calculus. p. 255.

- ↑ C. D. Yonge (1902). Gradus Ad Parnassum. London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. title.

- ↑ Henry Benjamin Wheatley (1891). London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Literary Blunders

- ↑ Thornbury, Walter (1878). 'Paternoster Row', in Old and New London. Volume 1. London, United Kingdom. pp. 274–281. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Thomas Bonnar: Overview of Thomas Bonnar". Scottish-places.info. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ↑ George Alexander Stevens (1771). The Choice Spirit's Chaplet: Or, a Poesy from Parnassus. Being a Select Collection of Songs, from the Most Approved Authors ; Many of Them Written and the Whole Compiled by George Alexander Stevens, Esq. John Dunn; and sold by Messrs. Hawes, Clarke, and Collins, London. pp. Title page.

- ↑ Zachary Grey (1740). A Vindication of the Government, Doctrine, and Worship, of the Church of England: Established in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. C. Davis, in Pater-Noster-Row.

- 1 2 Herbert Fry (1880), "Paternoster Row", London in 1880, London: David Bogue

Further reading

- John Wallis (1814), "Paternoster Row", London: being a complete guide to the British capital (4th ed.), London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, OCLC 35294736

- Henry Benjamin Wheatley (2011) [1891]. "Paternoster Row". London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-02808-0.