Hannah Glasse

| Hannah Glasse | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Hannah Allgood March 1708 London, England |

| Died |

1 September 1770 (aged 62) London, England |

| Occupation | Cookery writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Notable works |

The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy (1747) The Servants Directory (1757) |

| Spouse |

John Glasse (m. 1724–1747) |

| Children | 10 or 11 |

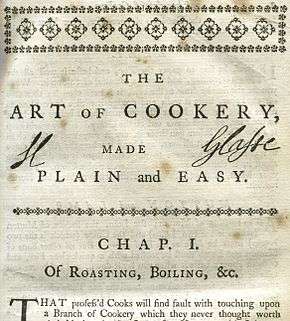

Hannah Glasse (née Allgood; March 1708 – 1 September 1770) was an English cookery writer of the 18th century. She is remembered mainly for her bestselling cookbook The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747. The book was reprinted within its first year of publication, appeared in 20 editions in the 18th century, and continued to be published until 1846.

Early life

Glasse was christened on 24 March 1708[2] at St Andrews, Holborn, London.[3]

Her father was Isaac Allgood,[2] a landowner of Brandon and Simonburn, both in Northumberland.[4] He married Hannah Clark, the daughter of a London vintner.[3] Hannah Glasse once described her mother in a letter as being a "wicked wretch!"[3][5]

On 5 August 1724, at Leyton, Hannah Glasse married an Irish soldier, John Glasse.[3][6][lower-alpha 1] Glasse's letters reveal that from 1728–32 the couple held positions in the household of the 4th Earl of Donegall at Broomfield, Essex. Thereafter, it seems, they lived in London.[3]

Glasse's identity as the author of one of the most popular of 18th-century cookery books was confirmed in 1938 by the historian Madeline Hope Dodds.[7]

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy was published by subscription in 1747, and also sold at "Mrs. Ashburn's, a China Shop, the corner of Fleet-Ditch" according to the title page. A second edition appeared before the year was out. The book did not reveal its authorship, using the vague cover "By a Lady". This permitted the erroneous claim that it was written by John Hill,[3] for instance in James Boswell's Life of Johnson. Johnson was not convinced.[3]

In 1747, the same year in which the book appeared, John Glasse died.[3][8] Also in that year, Glasse set herself up as a 'habitmaker' or dressmaker in Tavistock Street, Covent Garden,[3] in partnership with her eldest daughter, Margaret.

Later years

In 1754, Glasse was bankrupted.[3] Her stock was not auctioned after the bankruptcy, as it was all held in Margaret's name. However, on 29 October 1754, she was forced to auction her most prized asset, the copyright for The Art of Cookery.[3]

On 17 December 1754, The London Gazette stated that Glasse would be discharged from bankruptcy on 11 January 1755. Later that same year, she and her brother Lancelot repaid the sum of £500 they had jointly borrowed from Sir Henry Bedingfeld two years before.[9]

Her daughter paid the rates on the Tavistock premises for 1757, but the property was listed as empty next year[6], as Glasse had again fallen into financial difficulties and was consigned on 22 June 1757 to the Marshalsea debtors' prison[2]. In July 1757, she was transferred to Fleet Prison. No record has been found of her release date, but she was a free woman by 2 December 1757, as on this day she registered three shares in The Servants Directory, a new book she had written on the managing of a household. It was not a commercially successful venture, although its plagiarised editions were popular in North America[2].

In 1755, Ann Cook published Professed Cookery, containing a 68-page attack on Glasse.[3] Cook lived in Hexham, and was reacting to an alleged campaign of intimidation and persecution by Lancelot Allgood. In the same year, Glasse published her third and last work, The Compleat Confectioner. It was reprinted several times, but did not match the success that she had enjoyed with The Art of Cookery[6].

Family

Glasse and her husband had either ten or eleven children.[10][11][12]

Death

The London Gazette announced that "Mrs. Hannah Glasse, [half-]sister to Lancelot Allgood, died on 1 September 1770, aged 62".

Legacy

The instruction "First catch your hare" is sometimes misattributed to Glasse. The closest to it in her Art of Cookery is the recipe for roast hare (page 6) which begins "Take your hare when it be cas'd", meaning simply to take a skinned hare; this is likely to be the origin of the popular saying.[14][15]

In 1994, Prospect Books published a facsimile of the 1747 edition of Art of Cookery under the title First Catch Your Hare, with introductory essays by Jennifer Stead and Priscilla Bain, and a glossary by Alan Davidson; it was reissued in paperback in 2004. In 1998, Applewood Books published a facsimile edition of the 1805 edition, annotated by culinary historian Karen Hess. In 2006, Glasse was the subject of a BBC drama-documentary that called her the "mother of the modern dinner party", and "the first domestic goddess".[10]

Walter Staib serves Glasse's recipes in the City Tavern, Philadelphia, and praises her in his colonial cookbooks and his television show, A Taste of History.[16][17]

The 310th anniversary of Hannah Glasse's birthday was the subject of a Google Doodle on 28 March 2018.[18]

Notes

- ↑ John Glasse was retired on half pay, formerly in the household of Lord Polwarth, and a recent widower. Allgood Papers, Northumberland County Record Office Collections

References

- ↑ Prince, Rose (23 June 2006). "Hannah Glasse: The original domestic goddess". The Independent.

- 1 2 3 4 Robb-Smith, Alastair (2004). "Glasse [née Allgood] Hannah". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10804.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Wright, Clarissa Dickson (2012). A History of English Food. Arrow Books. pp. 295–296. ISBN 978-1-4481-0745-2.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Eneas; Ross, Metcalf (1834). An Historical, Topographical and Descriptive View of the County Palatine of Durham. 2. Mackenzie and Dent.

- ↑ Allgood Papers, Northumberland County Record Office Collections

- 1 2 3 Boyle, Laura (13 October 2011). "Hannah Glasse profile". The Jane Austen Centre. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Dodds, Madeleine Hope (1938). "The Rival Cooks: Hannah Glasse and Ann Cook" (PDF). Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. 15: 43–68.

- ↑ "Will of John Glasse of Saint Andrew Holborn, Middlesex, Prerogative Court of Canterbury, PROB11/755". 1 July 1747.

- ↑ Document ZSW/44/6 Northumberland County Record Office Collection

- 1 2 Prince, Rose (24 June 2006). "Hannah Glasse: The original domestic goddess". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ CLRO, Estates of insolvent debtors' MSS, Glasse 1757

- ↑ Weedon, M. J. P. (1 June 1949). "Richard Johnson and the Successors to John Newbery". The Library. s5-IV (1): 25–63. doi:10.1093/library/s5-iv.1.25 – via Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The Times, 12 December 1845, pg. 6

- ↑

- ↑ Acquired Tastes: Celebrating Australia's Culinary History, Colin Bannerman (and others), published by the National Library of Australia, 1998; ISBN 0-642-10693-2, pg. 2

- ↑ Staib, Walter. City Tavern Cookbook: 200 Years of Classic Recipes from America's First Gourmet Restaurant, pp. 9, 212, Running Press, Philadelphia, London, 1999; ISBN 0-7624-0529-5.

- ↑ Staib, Walter. City Tavern Baking & Dessert Cookbook: 200 Years of Authentic American Recipes from Martha Washington's Chocolate Mousse Cake to Thomas Jefferson's Sweet Potato Biscuits, pp. 43, 49, 67, 99, 121, 137, 149, 171, 211, 217, Running Press, Philadelphia, London, 2003; ISBN 0-7624-1554-1.

- ↑ "Hannah Glasse's 310th Birthday". Google Doodle. 28 March 2018.

External links

- "Extract of Art of Cookery". from the British Library (and biographical information)

- "Notes] and excerpts from the text".

- "Complete version of the Art of Cookery] at Foods of England".

- "City Tavern website".

- Works by Hannah Glasse at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)