Parliamentary train

Parliamentary trains in the United Kingdom were passenger services required by an Act of Parliament passed in 1844 to allow inexpensive and basic rail transport for less affluent passengers. That legislation required that at least one such service per day be run on every railway route in the UK. Now no longer a legal requirement (although most franchise agreements require such trains), the term describes train services that continue to be run to avoid the cost of formal closure of a route or station but with reduced services often to just one train per week and without specially low prices. Such services are often called "ghost trains".[1]

Nineteenth-century usage

In the earliest days of passenger railways in the United Kingdom the poor were encouraged to travel in order to find employment in the growing industrial centres, but trains were generally unaffordable to them except in the most basic of open wagons, in many cases attached to goods trains.[2] Political pressure caused the Board of Trade to investigate, and Sir Robert Peel's Conservative government enacted the Railway Regulation Act, which took effect on 1 November 1844. It compelled "the provision of at least one train a day each way at a speed of not less than 12 miles an hour including stops, which were to be made at all stations, and of carriages protected from the weather and provided with seats; for all which luxuries not more than a penny a mile might be charged".[3]

In popular culture

_(14778579752).jpg)

The basic comfort and slow progress of Victorian parliamentary trains led to a humorous reference in Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera The Mikado. The Mikado is explaining how he will match punishments to the crimes committed:

"The idiot who, in railway carriages

Scribbles on window-panes

We only suffer

To ride on a buffer

On Parliamentary trains."

Legacy of the Beeching closures

In 1963 the nationalised British Railways produced a report, The Reshaping of British Railways,[4] designed to stem the huge losses made by the railway industry. The chairman of British Railways was Richard Beeching, and the report became known as the Beeching Report. It proposed very substantial cuts to the network and to train services. The Transport Act 1962 included a formal closure process allowing for objections to closures on the basis of hardship to passengers if their service was closed. As the objections gained momentum, this process became increasingly difficult to implement, and from about 1970 closures slowed to a trickle.

In certain cases where there was exceptionally low usage the train service was reduced to a bare minimum, but the service was not formally closed, avoiding the costs associated with closure. In some cases the service was reduced to one train a week, and in one direction only.

These minimal services had resonances of the 19th-century parliamentary services, and among rail enthusiasts they came to be referred to as "parliamentary trains", or more colloquially "parly" trains (following the abbreviation used in Victorian timetables) or "ghost trains". However, this terminology has no official standing. So-called Parliamentary services are also typically run at inconvenient times, often very early in the morning, very late at night, or in the middle of the day at the weekend. In extreme instances, rail services have actually been "temporarily" withdrawn and replaced by substitute bus services, to maintain the pretence that the service has not been withdrawn.

Speller Act

When the closures brought about by the Beeching Report had reached equilibrium it was recognised that some incremental services or station reopenings were desirable. However, if a service was started and proved unsuccessful, it could not be closed again without going through the formal process, with the possibility that it might not be terminated. It was recognised that this discouraged possible desirable developments, and the Transport Act 1962 (Amendment) Act 1981 permitted the immediate closure of such experimental reopenings. The Bill that led to the Act of 1981 was sponsored by a pro-railways Member of Parliament, Antony Speller, and it is usually referred to as the Speller Act. The process is still in effect, although the legislation has been subsumed into other enactments.

Examples of extant "parliamentary" trains

Some current examples of lines served only by a "Parliamentary" train are:

| Origin | Destination | Departure | Operator | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chester | Runcorn | 07:53 Saturday, summer only | Arriva Rail North | Via the one-way Halton Curve, northbound only.[5][6] |

| Stalybridge | Stockport | 08:46 Stalybridge 09:45 Stockport |

Arriva Rail North | Stockport to Stalybridge Line Saturday only |

| Lancaster | Windermere, via Morecambe | 05:40 Monday–Saturday | Arriva Rail North | Via the Morecambe–Hest Bank line. The same line is also used by the 16:05 Lancaster-Leeds via Morecambe train on Monday–Fridays and the 14:29 Lancaster-Morecambe-Leeds on Sundays (no return journey in all cases). |

| South Ruislip | London Paddington | 11:35 weekdays | Chiltern Railways | From Paddington at 11:36 to High Wycombe serves the purpose of maintaining route knowledge for Chiltern Railways drivers enabling the company to divert services to Paddington in the event that Marylebone is closed.[7][8] |

| Wolverhampton | Walsall | 06:38 Saturday | West Midlands Trains | No return journey. The regular Walsall to Wolverhampton service runs via Birmingham New Street rather than over the direct line. |

| Sheffield | Cleethorpes via Retford and Brigg | 08:03, 12:00 & 16:00 Saturday | Arriva Rail North | Trains return from Cleethorpes at 11:10, 15:20 and 18:36. |

| Goole | Leeds via Knottingley | 07:04 & 18:49 Monday–Saturday | Arriva Rail North | One return journey at 17:16. |

| Battersea Park | Dalston Junction | 06:18 & 23:03 Monday–Saturday | London Overground | 22:06 Dalston Junction to Battersea Park return journey. |

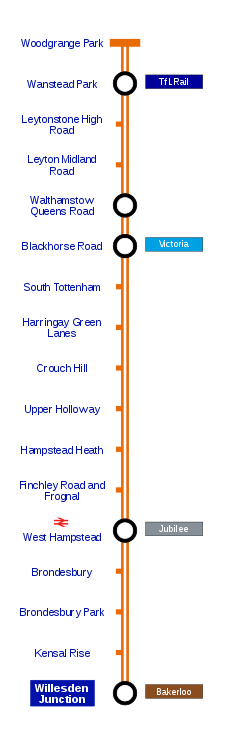

| London Liverpool Street | Enfield Town via South Tottenham | 05:31 Saturday | London Overground | No return journey. Does not call at South Tottenham. |

| London Bridge | Streatham Hill via Tulse Hill and the Leigham Spur | 10:01 Monday–Friday | Southern | No return journey. |

| London Charing Cross | Tunbridge Wells via Beckenham Junction | 00:15 Tuesday–Saturday | Southeastern | Return at 04:49 from Tonbridge to London Charing Cross via Beckenham Junction, Monday–Friday only. These journeys use the curve between Beckenham Junction and New Beckenham (previously used by a weekday morning Cannon Street to Beckenham Junction via New Beckenham train, returning in the afternoon to Charing Cross). |

| Gillingham (Kent) | Sheerness-on-Sea | 04:56 Monday–Friday | Southeastern | Return at 21:32, using the Sittingbourne Western Junction curve. |

| An up-to-date list is maintained at the "PSUL". website.[9] | ||||

A station may have a "parliamentary" service because the operating company wishes it closed, but the line is in regular use (most trains pass straight through). Examples include:

- Teesside Airport, which serves Durham Tees Valley Airport in Country Durham, lost most of its services due to its relatively long distance to the terminal as well as competition from buses which offered more reliable services (which in turn were withdrawn due to the airport's sharp decrease in air passengers). The current service is operated only on Sundays and comprises the 10:29 from Darlington-Metrocentre via Hartlepool with a return at 12:19. Operated by Arriva Rail North.[11]

- Pilning in South Gloucestershire, near Bristol – only two trains per week, both from Cardiff Central to Taunton. These departures are on Saturdays only at 08:35 and 13:34. Formerly one train each way per week, but the bridge to the down platform was removed in November 2016. Operated by Great Western Railway.[12]

- Barry Links and Golf Street in Carnoustie, Scotland. These are served by the 17:03 Glasgow Queen Street–Carnoustie service (17:11 Saturday) and the 06:00 Carnoustie–Dundee return. Operated by Abellio ScotRail.

- Shippea Hill in Cambridgeshire and Lakenheath in Suffolk (between Ely and Brandon on the Breckland Line to Norwich). Shippea Hill is served at 07:23 Mondays–Fridays (07:25 Saturday) Eastbound and 09:27 Saturdays only westbound. Lakenheath, however, is served by 7 trains on a Sunday. There are no services Monday–Friday and just a single journey in each direction on Saturdays.

- Polesworth has one train per day Mondays–Saturdays, northbound only at 07:23. After major works on the West Coast Main Line, contractors neglected to replace the footbridge which they had removed, leaving passengers unable to access southbound trains.

One train every Saturday is scheduled to call at Bordesley; however, the station remains open for use when Birmingham City Football Club are playing at home.

In the mid-1990s British Rail was forced to serve Smethwick West in the West Midlands for an extra 12 months after a legal blunder meant that the station had not been closed properly. One train per week each way still called at Smethwick West, even though it was only a few hundred yards from the replacement Smethwick Galton Bridge.[13]

A variant of the "parliamentary" train service was the "temporary" replacement bus service, as employed between Watford and Croxley Green in Hertfordshire. The railway line was closed to trains in 1996, but to avoid the legal complications and costs of actual closure train services were replaced by buses, thus maintaining the legal fiction of an open railway.[14] The branch was officially closed in 2003. Work is to begin to absorb most of the route into a diversion of the Watford branch of the Metropolitan line into Watford Junction.

The "temporary replacement bus" tactic was used from December 2008 between Ealing Broadway and Wandsworth Road[15] when CrossCountry withdrew its services from Brighton to the Northwest, which was the only passenger service between Factory Junction, north of Wandsworth Road, and Latchmere Junction, on the West London Line. This service was later replaced by a single daily return train between Kensington Olympia and Wandsworth Road operated by Southern until formal consultation commenced and closure was completed in 2013.[16]

The "replacement bus" tactic—on a long-term basis—is being used to cover Norton Bridge, Barlaston and Wedgwood stations on the Stafford–Manchester line, which had their passenger services withdrawn in 2004.

See also

References

- ↑ "On Board a Real-Life "Ghost Train"". BBC News. 1 July 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ↑ D.N. Smith (1988) The Railway and Its Passengers: A Social History, Newton Abbott: David & Charles

- ↑ MacDermott, E.T., History of the Great Western Railway, London: Great Western Railway, 1927, Vol. 1, part 2, page 640

- ↑ "The Reshaping of British Railways" (PDF). Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1963.

- ↑ Rural Railways – Fifth Report of the Session 2004–05 (PDF), The Stationery Office, 9 March 2005, retrieved 16 September 2009

- ↑ Hearfield, Samuel (2016-10-15). "Chester to Liverpool South Parkway (Parliamentary Train) Via the Halton Curve (Final Trip, 16th of July 2016)". Samuel Hearfield (YouTube). Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Marshall, Geoff (2015-06-11). "Paddington to West Ruislip Ghost Train". Londonist Ltd (YouTube). Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ↑ Marshall, Geoff (11 June 2015). "Paddington To West Ruislip Ghost Train". Londonist. London.

- ↑ "Passenger Train Services over Unusual Lines". Branchline.uk. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "PSUL 2016". Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Rail buffs to highlight Teesside Airport 'ghost station'". The Journal. Trinity Mirror. 14 October 2009. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- ↑ "All aboard for the ghost train". Western Daily Press. 10 August 2006.

- ↑ "Smethwick West Station 1867–1996". railaroundbirmingham.co.uk. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ↑ "Croxley Green LNWR branch - passenger closure". Rail Chronology. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "'Ghost bus' makes final journey"itv.com news article 11 June 2013; Retrieved 20 May 2013

- ↑ "Consultation: Withdrawal of scheduled passenger services between Wandsworth Road, Kensington (Olympia) and Ealing Broadway". Department for Transport. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

Bibliography

- Billson, P. (1996). Derby and the Midland Railway. Derby: Breedon Books.

- Jordana, Jacint; Levi-Faur, David (2004). The politics of regulation: institutions and regulatory reforms for the age of governance. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84376-464-9.

- Ransom, P. J. G. (1990). The Victorian Railway and How It Evolved. London: Heinemann.

- Calder, Simon (2011-04-02). "Missed the bus? The route that runs only four times year". BBC.