Parallel and counter parallel

In music, a parallel chord (relative chord, German: Parallelklang) is an auxiliary chord derived from one of the primary triads and sharing its function: subdominant parallel, dominant parallel, and tonic parallel.[4] The term is derived from German theory and the writings of Hugo Riemann (see: Riemannian theory).

The substitution of the major sixth for the perfect fifth above in the major triad and below in the minor triad results in the parallel of a given triad. In C major thence arises an apparent A minor triad (Tp, the parallel triad of the tonic, or tonic parallel), D minor triad (Sp), and E minor triad (Dp).

— Hugo Riemann, "Dissonance", Musik-Lexikon[5]

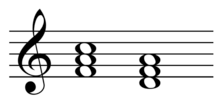

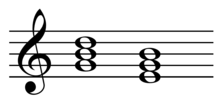

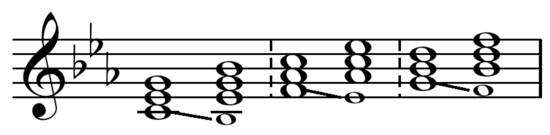

For example, the major ![]()

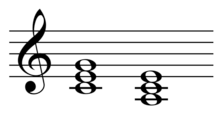

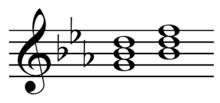

![]()

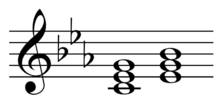

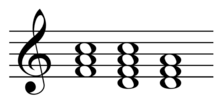

![]()

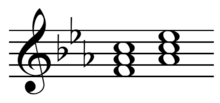

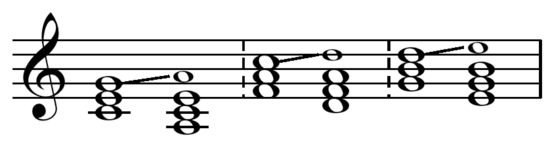

![]()

| Major | Minor | ||||

| Parallel | Note letter in C | Name | Parallel | Note letter in C | Name |

| Tp | A minor[6] | Submediant | tP | E♭ major[6] | Mediant |

| Sp | D minor[4][6] | Supertonic | sP | A♭ major[6] | Submediant |

| Dp | E minor[1][4][2][3][6] | Mediant | dP | B♭ major[1][4][6] | Subtonic |

Dp stands for Dominant-parallel. The word "parallel" in German has the meaning of "relative" in English. G major and E minor are called parallel keys. The G major chord and the E minor chord in the key of C major are called parallel chords in the Riemann system.

— [7]

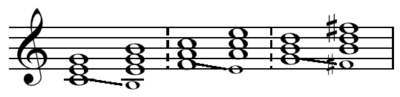

- The tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords, in root position, each followed by its parallel. The parallel is formed by raising the fifth a whole tone.

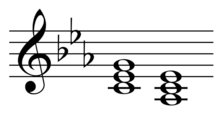

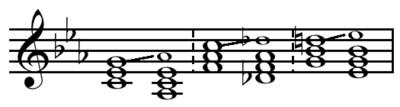

- The minor tonic, subdominant, dominant, and their parallels, created by lowering the fifth (German)/root (US) a whole tone.

The parallel chord (but not the counter parallel chord) of a major chord will always be the minor chord whose root is a minor third down from the major chord's root, inversely the parallel chord of a minor chord will be the major chord whose root is a minor third up from the root of the minor chord. Thus, in a major key, where the dominant is a major chord, the dominant parallel will be the minor chord a minor third below the dominant. In a minor key, where the dominant may be a minor chord, the dominant parallel will be the major chord a minor third above the (minor) dominant.

Dr. Riemann...sets himself to demonstrate that every chord within the key-system has, and must have, either a Tonic, Dominant or Subdominant function or significance. For example, the secondary triad on the sixth degree [submediant] of the scale of C major, a-c-e, or rather c-e-a, is a Tonic 'parallel,' and has a Tonic significance, because the chord represents the C major 'klang,' into which the foreign note a is introduced. This, as we have seen, is the explanation which Helmholtz has given of this minor chord."

— Shirlaw 2010[8]

The name "parallel chord" comes from the German musical theory, where "Paralleltonart" means not "parallel key" but "relative key", and "parallel key" is "Varianttonart".

Counter parallel

The "counter parallel" or "contrast chord" is terminology used in German theory derived mainly from Hugo Riemann to refer to (US:) relative (German: parallel) diatonic functions and is abbreviated Tcp in major and tCp in minor (Tkp respectively tKp in Riemann's diction). The chord can be seen as the "tonic parallel reversed" and is in a major key the same chord as the dominant parallel (Dp) and in a minor key equal to the subdominant parallel (sP); yet, it has another function. According to Riemann the chord is derived through Leittonwechselklänge (German, literally: "leading-tone changing sounds"), sometimes called gegenklang or "contrast chord", abbreviated Tl in major and tL in minor.[6] If chords may be formed by raising (major) or lowering (minor) the fifth a whole step ["parallel" or relative chords], they may also be formed by lowering (major) or raising (minor) the root a half-step to wechsel, the leading tone or leitton.

| Major | Minor | ||||

| Contrast | Note letter in C | Name | Contrast | Note letter in C | Name |

| Tl (Tcp) | E minor[6] | Mediant | tL (tCp) | A♭ major[6] | Submediant |

| Sl (Scp) | A minor[6] | Submediant | sL (sCp) | D♭ major[6] | Neapolitan chord |

| Dl (Dcp) | B minor[6] | Leading-tone | dL (dCp) | E♭ major[6] | Mediant |

The substitution of the leading tone for the prime (from below [<] in major, from above [>] in minor) likewise results...in the leading-tone change (in C major: T< = E minor, S< = A minor, D< = B minor[!]; in A minor: T> = F major, D> = C major, S> = B major [!].

— Hugo Riemann, "Dissonance", Musik-Lexikon[5]

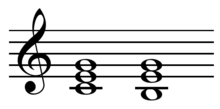

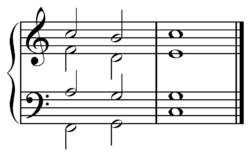

- Major Leittonwechselklänge, formed by lowering the root a half step.

- Minor Leittonwechselklänge, formed by raising the root (US)/fifth (German) a half step.

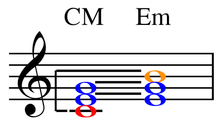

For example, Am is the tonic parallel of C, thus, Em is the counter parallel of C. The usual parallel chord in a major key is a minor third below the root and the counter parallel is a major third above. In a minor key the intervals are reversed: the tonic parallel (e.g. Eb in Cm) is a minor third above, and the counter parallel (e.g. Ab in Cm) is a major third below. Both the parallel and the counter parallel have two notes in common with the tonic (Am and C share C & E; Em and C share E & G).

A chord should be analysed as a Tcp rather than Dp or sP particularly at cadential points, for example at an interrupted cadence, where it substitutes the tonic. It is most easily recognised in a minor key since it creates an ascending semitone step at the end of the cadence by moving from the major dominant chord to the minor counter parallel:

Ex. t - s - D - tCp Em - Am - B - C

where C is located a major third below Em

Ex. T - S - D - tCp F - Bb - C - Db

where Db is located a major third below the minor tonic Fm

In four-part harmony, the Tcp usually has a doubled third to avoid consecutive fifths or octaves. This further emphasises its coherency with the tonic, since the third of the minor key counter parallel is the same as the tonic root which thus is doubled.

This is clearly not a simple system. Three functional categories can appear in any one of three chordal guises in either of two modes, eighteen possibilities in all: T, Tp, Tl, t, tP, tL, S, Sp, Sl, s, sP, sL, D, Dp, Dl, d, dP, dL. Why all this complexity? Perhaps the central reason is that this ingenious, occasionally convoluted system enabled Riemann to...[interpret] ostensibly remote triads...through the traditional terms of the I-IV-V-I, or now T-S-D-T, cadential schema. A sequence of A♭-major, B♭-major, and C-major chords, for example, could be neatly interpreted as a subdominant (sP) to dominant (dP) to tonic (T) progression in C-major, a reading...not without support in certain late-Romantic cadences.

— Gjerdingen[6]

See also

Sources

- 1 2 3 Goetschius, Percy and Faisst, Immanuel (1889). The Material Used in Musical Composition, p.139. G. Schirmer.

- 1 2 Kober, Thorsten (2003). Guitar Works: A Comprehensive Guide to Playing the Guitar, p.136. ISBN 978-0-634-03123-6.

- 1 2 Sebastian Kalamajski (2000). All Aspects of Rock & Jazz, p.35. ISBN 978-87-88619-68-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Haunschild, Frank (2000). The New Harmony Book, p.47. ISBN 978-3-927190-68-9.

- 1 2 Gollin, Edward and Rehding, Alexander; eds. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Music Theories, p.105. Oxford. ISBN 9780195321333.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Gjerdingen, Robert O. (1990). "A Guide to the Terminology of German Harmony", Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality by Dahlhaus, Carl, trans. Gjerdingen (1990), p.xiii. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

- ↑ Gail Boyd de Stwolinski Center for Music Theory Pedagogy (1993). Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, Volumes 5-7, p.37, n.9. School of Music, The University of Oklahoma.

- ↑ Shirlaw, Matthew (reprinted 2010). The Theory of Harmony: An Inquiry Into the Natural Principles of Harmony, With an Examination of the Chief Systems of Harmony from Rameau to the Present Day, p.401. ISBN 1-4510-1534-8. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-09-01. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

External links

- "Chord Functions", NiklasAndreasson.se.

- “A Guide to the Terminology of German Harmony”, in Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, pp. xi–xv (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1990). "Published Papers", Robert Gjerdingen.