Padstow

Padstow

| |

|---|---|

Padstow Harbour and quayside | |

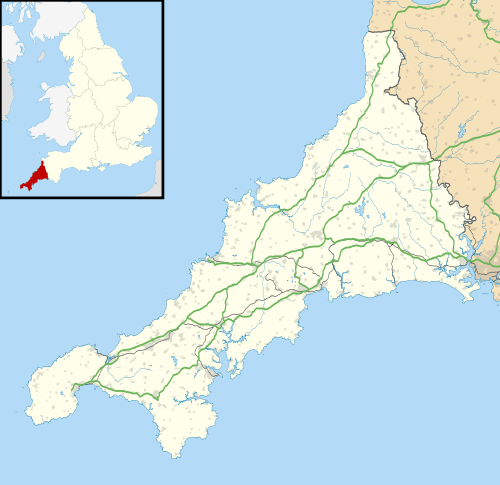

Padstow Padstow shown within Cornwall | |

| Population | 2,993 (Civil Parish, 2011) |

| OS grid reference | SW918751 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PADSTOW |

| Postcode district | PL28 |

| Dialling code | 01841 |

| Police | Devon and Cornwall |

| Fire | Cornwall |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| EU Parliament | South West England |

| UK Parliament | |

Padstow (/ˈpædstoʊ/; Cornish: Lannwedhenek[1]) is a town, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Wadebridge, 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Bodmin and 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Newquay.[2] The population of Padstow civil parish was 3,162 in the 2001 census,[3] reducing to 2,993 at the 2011 census.[4] In addition an electoral ward with the same name exists but extends as far as Trevose Head. The population for this ward is 4,434[5]

History

.jpg)

Padstow was originally named Petroc-stow, Petroc-stowe, or 'Petrock's Place', after the Welsh missionary Saint Petroc, who landed at Trebetherick around AD 500. After his death a monastery (Lanwethinoc, the church of Wethinoc, an earlier holy man) was established here which was of great importance until "Petroces stow" (probably Padstow) was raided by the Vikings in 981, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[6] Whether as a result of this attack or later, the monks moved inland to Bodmin, taking with them the relics of St Petroc.[7] The cult of St Petroc was important both in Padstow and Bodmin.

Padstow is recorded in the Domesday Book (1086) when it was held by Bodmin Monastery. There was land for 4 ploughs, 5 villeins who had 2 ploughs, 6 smallholders and 24 acres of pasture. It was valued at 10/- (10 shillings or 50p).[8]

In the medieval period Padstow was commonly called Aldestowe ('old place' in contrast to Bodmin, the 'new place').[9] or Hailemouth ("hayle" being Cornish for estuary). The modern Cornish form Lannwedhenek derives from Lanwethinoc and in a simpler form appears in the name of the Lodenek Press, a publisher based in Padstow.

The seal of the borough of Padstow was a ship with three masts, the sails furled and an anchor hanging from the bow, with the legend "Padstow." [10]

Time Team visited Padstow for the episode "From Constantinople to Cornwall," broadcast on 9 March 2008.

There are two Cornish crosses in the parish: one is built into a wall in the old vicarage garden and another is at Prideaux Place (consisting of a four-holed head and part of an ornamented cross shaft). There is also part of a decorated cross shaft in the churchyard.[11]

Churches

The church of St Petroc is one of four said to have been founded by the saint, the others being Little Petherick, Parracombe and Bodmin. It is quite large and mostly of 13th and 14th century date. There is a fine 15th century font of Catacleuse; the pulpit of c. 1530 is also of interest. There are two fine monuments to members of the Prideaux family (Sir Nicholas, 1627 and Edmund, 1693): there is also a monumental brass of 1421.[12]

Economy

Traditionally a fishing port, Padstow is now a popular tourist destination. Although some of its former fishing fleet remains, it is mainly a yachting haven on a dramatic coastline with few easily navigable harbours. The influence of restaurateur Rick Stein can be seen in the port, and tourists travel from long distances to eat at his restaurant and cafés. This has led to the town being dubbed "Padstein", by food writers in the British media.[13][14][15]

However, the boom in the popularity of the port has caused house price inflation both in the port and surrounding areas, as people buy homes to live in, or as second or holiday homes. This has meant significant numbers of locals cannot afford to buy property in the area, with prices often well over 10 times the average salary of around £15,000. This has led to a population decline.

Plans to build a skatepark in Padstow have been proposed and funds are being raised to create this at the Recreation Ground (Wheal Jubilee Parc).[16]

Transport

Maritime traffic

During the mid-19th century, ships carrying timber from Canada (particularly Quebec City) would arrive at Padstow and offer cheap travel to passengers wishing to emigrate. Shipbuilders in the area would also benefit from the quality of their cargoes. Among the ships that sailed were the barques Clio, Belle[17] and Voluna; and the brig Dalusia.[18]

The approach from the sea into the River Camel is partially blocked by the Doom Bar, a bank of sand extending across the estuary which is a significant hazard to shipping and the cause of many shipwrecks.

For ships entering the estuary, the immediate loss of wind due to the cliffs was a particular hazard, often resulting in ships being swept onto the Doom Bar. A manual capstan was installed on the west bank of the river (its remains can still be seen) and rockets were fired to carry a line to ships so that they could be winched to safety.

There have been ferries across the Camel estuary for centuries and the current service, the Black Tor Ferry, carries pedestrians between Padstow and Rock daily throughout the year.

Railway

From 1899 until 1967 Padstow railway station was the westernmost point of the former Southern Railway. The railway station was the terminus of an extension from Wadebridge of the former Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway and North Cornwall Railway. These lines were part of the London and South Western Railway (LSWR), then incorporated into the Southern Railway in 1923 and British Railways in 1948, but were proposed for closure during the Beeching Axe of the 1960s.

The LSWR (and Southern Railway) promoted Padstow as a holiday resort; these companies were rivals to the Great Western Railway (which was the larger railway in the West of England). Until 1964, Padstow was served by the Atlantic Coast Express – a direct train service to/from London (Waterloo) – but the station was closed in 1967. The old railway line is now the Camel Trail,[19] a footpath and cycle path which is popular owing to its picturesque route beside the River Camel. One of the railway mileposts is now embedded outside the Shipwright's Arms public house on the Harbour Front.

Today, the nearest railway station is at Bodmin Parkway, a few miles south of Bodmin. Plymouth Bus operate buses to the station.

Footpaths

The South West Coast Path runs on both sides of the River Camel estuary and crosses from Padstow to Rock via the Black Tor ferry. The path gives walking access to the coast with Stepper Point and Trevose Head within an easy day's walk of Padstow.

The Saints' Way long-distance footpath runs from Padstow to Fowey on the south coast of Cornwall.

The Camel Trail cycleway follows the course of the former railway (see above) from Padstow. It is open to walkers, cyclists and horse riders and suitable for disabled access. The 17.3-mile (27.8 km) long route leads to Wadebridge and on to Wenford Bridge and Bodmin, and is used by an estimated 400,000 users each year[20] generating an income of approximately £3 million a year.[20]

Culture

'Obby 'Oss festival

Padstow is best known for its "'Obby 'Oss" festival. Although its origins are unclear, it most likely stems from an ancient fertility rite, perhaps the Celtic festival of Beltane. The festival starts at midnight on May Eve when townspeople gather outside the Golden Lion Inn to sing the "Night Song." By morning, the town has been dressed with greenery and flowers placed around the maypole. The excitement begins with the appearance of one of the 'Obby 'Osses. Male dancers cavort through the town dressed as one of two 'Obby 'Osses, the "Old" and the "Blue Ribbon" 'Obby 'Osses; as the name suggests, they are stylised kinds of horses. Prodded on by acolytes known as "Teasers," each wears a mask and black frame-hung cape under which they try to catch young maidens as they pass through the town. Throughout the day, the two parades, led by the "Mayer" in his top hat and decorated stick, followed by a band of accordions and drums, then the 'Oss and the Teaser, with a host of people - all singing the "Morning Song." - pass along the streets of the town. Finally, late in the evening, the two 'osses meet, at the maypole, before returning to their respective stables where the crowd sings of the 'Obby 'Oss death, until its resurrection the following May Eve.

Mummers' or Darkie Day

On Boxing Day and New Year's Day, it is a tradition for some residents to don blackface and parade through the town singing 'minstrel' songs. This is an ancient midwinter celebration that occurs every year in Padstow and was originally part of the pagan heritage of midwinter celebrations that were regularly celebrated all over Cornwall where people would guise dance and disguise themselves by blackening up their faces or wearing masks. Recently (since 2007), the people of Penzance have revived its midwinter celebration with the Montol Festival which like Padstow at times would have had people darkening or painting their skin to disguise themselves as well as masking.)

Folklorists associate the practice with the widespread British custom of blacking up for mumming and morris dancing, and suggest there is no record of slave ships coming to Padstow. Once an unknown local charity event, the day has recently become controversial, perhaps since a description was published.[21] Also some now suggest it is racist for white people to "black up" for any reason.[22] Although "outsiders" have linked the day with racism, Padstonians insist that this is not the case and are incredulous at both description and allegations. Long before the controversy Charlie Bate, noted Padstow folk advocate, recounted that in the 1970s the content and conduct of the day were carefully reviewed to avoid potential offence.[23] The Devon and Cornwall Constabulary have taken video evidence twice and concluded there were no grounds for prosecution.[24] Nonetheless protests resurface annually. The day has now been renamed Mummers' Day in an attempt to avoid offence and identify it more clearly with established Cornish tradition.[25] The debate has now been subject to academic scrutiny.[26]

Other similar traditions that use the black-face disguise and are still celebrated within the United Kingdom are the Border Morris dancers, and Molly dancers of the East Midlands and East Anglia.

Notable residents

- Donald Rawe, Cornish publisher, dramatist, novelist, and poet, was born in Padstow. He became a member of Gorseth Kernow in 1970, under the Bardic name of Scryfer Lanwednoc ('Writer of Padstow').[27]

- Rick Stein, restaurateur and celebrity chef, owns several restaurants and businesses in the town.

- Enys Tregarthen, author and folklorist

- Paul Ainsworth, Michelin starred chef, runs several businesses in Padstow

See also

References

- ↑ "List of Place-names agreed by the MAGA Signage Panel" (PDF). Cornish Language Partnership. May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 200 Newquay & Bodmin ISBN 978-0-319-22938-5

- ↑ Parish population for North Cornwall district Archived 7 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine., Cornwall County Council and ONS, 2001

- ↑ "Parish population 2011". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ward population 2011 census". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; p. 10 "[either Padstow or Bodmin] ... presumably by a Viking attack"

- ↑ Orme (2007); p. 10

- ↑ Thorn, C., et al., eds. (1979) Cornwall. (Domesday Book; 10.) Chichester: Phillimore; entry 4,4

- ↑ Henderson, C. "Parochial history [of] Padstow", in: Cornish Church Guide (1925). Truro: Blackford, pp. 173-74)

- ↑ Pascoe, W. H. (1979). A Cornish Armory. Padstow, Cornwall: Lodenek Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-902899-76-7.

- ↑ Langdon, A. G. (1896) Old Cornish Crosses. Truro: Joseph Pollard; pp. 196-97, 396-98 & 407-10

- ↑ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1970) Cornwall, 2nd ed. Penguin Books; pp. 129-130

- ↑ Savill, Richard (14 October 2008). "Rick Stein defends impact of his seafood empire on Padstow". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ "The battle of 'Padstein': TV chef Rick Stein at war with the locals". dailymail.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Gerard, By Jasper. "Rick Stein's Seafood Restaurant in Padstow". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Padstow Skate Park: Home Page". padstowskatepark.org. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Kohli, Marj. "Immigrants to Canada - Vessels Arriving at Quebec 1843". ist.uwaterloo.ca. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ "RootsWeb.com Home Page". freepages.history.rootsweb.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ "MacAce Test Page". www.cameltrail.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- 1 2 North Cornwall District Council (June 2003). "North Cornwall Matters - Partnership Improves The Trail" (PDF). North Cornwall Matters. North Cornwall District Council. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- ↑ J. R. Daeschner, True Brits (Arrow, London, 2004)

- ↑ "Way out West", The Guardian 3 January 2007

- ↑ M. O'Connor, Ilow Kernow 3 (St Ervan, 2005) p27

- ↑ "No action on town's 'Darkie Day'". BBC News. 10 March 2005. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ↑ "MP calls for 'Darkie Day' to stop". BBC News. 11 January 2006. Archived from the original on 29 January 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ↑ M. Davey, Guizing: Ancient Traditions and Modern Sensitivities, In: P. Payton (ed), Cornish Studies 14 (Exeter, 2006) p.229

- ↑ "Passionate patriot's book is a cracking yarn full of originality and enthusiasm". This Is Cornwall. 8 June 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011.

- Henderson, Charles (1938) "Padstow Church and Parish" in: Doble, G. H. Saint Petrock, a Cornish Saint; 3rd ed. [Wendron: the author]; pp. 51–59

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Padstow. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Padstow. |