Pablo Escobar

| Pablo Escobar | |

|---|---|

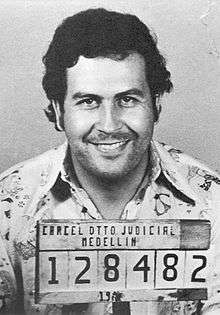

A mugshot of Pablo Escobar taken in 1977 by the Medellín Control Agency. | |

| Born |

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria 1 December 1949 Rionegro, Colombia |

| Died |

2 December 1993 (aged 44) Medellín, Colombia |

| Cause of death | Shooting |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Founder and head of the Medellín Cartel, and politician |

| Net worth | US$30 billion (1993 estimate) |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Victoria Henao (1976–1993; his death) |

| Children |

|

| Conviction(s) | Drug trafficking and smuggling, assassinations, bombing, bribery, racketeering, murder |

| Criminal penalty | 5 years imprisonment[1] |

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpaβ̞lo eˈmiljo eskoˈβ̞aɾ ɣ̞aˈβ̞iɾja]; 1 December 1949 – 2 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist. His cartel supplied an estimated 80% of the cocaine smuggled into the United States at the height of his career, turning over US$21.9 billion a year in personal income.[2][3] He was often called "The King of Cocaine" and was the wealthiest criminal in history, with an estimated known net worth of between US$25 and US$30 billion by the early 1990s (equivalent to between about $48.5 and $56 billion as of 2017),[4][5] making him one of the richest men in the world in his prime.[6][7]

Escobar was born in Rionegro, Colombia, and grew up in nearby Medellín. He studied briefly at Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellin but left without a degree; he began to engage in criminal activity that involved selling contraband cigarettes and fake lottery tickets, and he participated in motor vehicle theft. In the 1970s, he began to work for various contraband smugglers, often kidnapping and holding people for ransom before beginning to distribute powder cocaine himself, as well as establishing the first smuggling routes into the United States in 1975. His infiltration to the drug market of the U.S. expanded exponentially due to the rising demand for cocaine; and, by the 1980s, it was estimated that 70 to 80 tons of cocaine were being shipped from Colombia to the U.S. monthly. His drug network was commonly known as the Medellín Cartel, which often competed with rival cartels domestically and abroad, resulting in massacres and the murders of police officers, judges, locals, and prominent politicians.

In 1982, Escobar was elected as an alternate member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia as part of the Liberal Alternative movement. Through this, he was responsible for the construction of houses and football fields in western Colombia, which gained him notable popularity among the locals of the towns that he frequented. However, Colombia became the murder capital of the world, and Escobar was vilified by the Colombian and American governments.[8] In 1993, Escobar was shot and killed in his hometown by Colombian National Police, one day after his 44th birthday.[9][10]

Early life

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on 1 December 1949, in Rionegro, in the Antioquia Department of Colombia. He was the third of seven children of the farmer Abel de Jesús Dari Escobar Echeverri (1910–2001),[11] with his wife Hemilda de los Dolores Gaviria Berrío (d. 2006),[12] an elementary school teacher.[13] Raised in the nearby city of Medellín, Escobar is thought to have begun his criminal career as a teenager, allegedly stealing gravestones and sanding them down for resale to local smugglers. His brother, Roberto Escobar, denies this, instead claiming that the gravestones came from cemetery owners whose clients had stopped paying for site care, and that he had a relative who had a monuments business.[14] Escobar's son, Sebastián Marroquín, claims his father's foray into crime began with a successful practice of selling counterfeit high school diplomas,[7] generally counterfeiting those awarded by the Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellín. Escobar studied at the University for a short period, but left without obtaining a degree.[15]

Escobar eventually became involved in many criminal activities with Oscar Benel Aguirre, with the duo running petty street scams, selling contraband cigarettes, fake lottery tickets, and stealing cars.[16] In the early 1970s, prior to entering the drug trade, Escobar acted as a thief and bodyguard, allegedly earning US $100,000 by kidnapping and holding a Medellín executive for ransom.[17] Escobar began working for Alvaro Prieto, a contraband smuggler who operated around Medellín, aiming to fulfill a childhood ambition to have COL $1 million by the time he was 22.[18] Escobar is noted for his bank deposit of COL $100 million (more than US $3 million), when he turned 26.[19]

Criminal career

Cocaine distribution

In The Accountant's Story, Roberto Escobar discusses the means by which Pablo rose from middle-class simplicity and obscurity to one of the world's wealthiest men. Beginning in 1975, Pablo started developing his cocaine operation, flying out planes several times, mainly between Colombia and Panama, along smuggling routes into the United States. When he later bought fifteen bigger airplanes, including a Learjet and six helicopters, according to his son, a dear friend of Pablo's died during the landing of an airplane, and the plane was destroyed. Pablo reconstructed the airplane from the scrap parts that were left and later hung it above the gate to his ranch at Hacienda Nápoles.

In May 1976, Escobar and several of his men were arrested and found in possession of 39 pounds (18 kg) of white paste, attempting to return to Medellín with a heavy load from Ecuador. Initially, Pablo tried to bribe the Medellín judges who were forming a case against him, and was unsuccessful. After many months of legal wrangling, he ordered the murder of the two arresting officers, and the case was later dropped. Roberto Escobar details this as the point where Pablo began his pattern of dealing with the authorities, by either bribery or murder.[20]

Roberto Escobar maintains Pablo fell into the drug business simply because other types of contraband became too dangerous to traffic. As there were no drug cartels then, and only a few drug barons, Pablo saw it as untapped territory he wished to make his own. In Peru, Pablo would buy the cocaine paste, which would then be refined in a laboratory in a two-story house in Medellín. On his first trip, Pablo bought a paltry 30 pounds (14 kg) of paste in what was noted as the first step towards building his empire. At first, he smuggled the cocaine in old plane tires, and a pilot could return as much as US $500,000 per flight, dependent on the quantity smuggled.[21]

Rise to prominence

Soon, the demand for cocaine was skyrocketing in the United States, and Escobar organized more smuggling shipments, routes, and distribution networks in South Florida, California, and other parts of the country. He and cartel co-founder Carlos Lehder worked together to develop a new trans-shipment point in the Bahamas, an island called Norman's Cay about 220 miles (350 km) southeast of the Florida coast. According to his brother, Escobar did not purchase Norman's Cay; it was, instead, a sole venture of Lehder's. Escobar and Robert Vesco purchased most of the land on the island, which included a 1 kilometre (3,300 ft) airstrip, a harbor, a hotel, houses, boats, and aircraft, and they built a refrigerated warehouse to store the cocaine. From 1978 to 1982, this was used as a central smuggling route for the Medellín Cartel. With the enormous profits generated by this route, Escobar was soon able to purchase 7.7 square miles (20 km2) of land in Antioquia for several million dollars, on which he built the Hacienda Nápoles. The luxury house he created contained a zoo, a lake, a sculpture garden, a private bullring, and other diversions for his family and the cartel.[22]

At one point it was estimated[23] that 70 to 80 tons of cocaine were being shipped from Colombia to the United States every month. In the mid-1980s, at the height of its power, the Medellín Cartel was shipping as much as 11 tons per flight in jetliners to the United States (the biggest load shipped by Escobar was 51,000 pounds (23,000 kg) mixed with fish paste and shipped via boat, as confirmed by his brother in the book Escobar). Roberto Escobar also claimed that, in addition to using planes, his brother employed two small submarines to transport the massive loads.[2]

Established drug network

In 1982 Escobar was elected as an alternate member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia, as part of a small movement called Liberal Alternative. Earlier in the campaign he was a candidate for the Liberal Renewal Movement, but had to leave it because of the firm opposition of Luis Carlos Galán, whose presidential campaign was supported by the Liberal Renewal Movement.[24][25] Escobar was the official representative of the Colombian government for the swearing-in of Felipe González in Spain.[26]

Escobar quickly became known internationally as his drug network gained notoriety; the Medellín Cartel controlled a large portion of the drugs that entered the United States, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Spain. The production process was also altered, with coca from Bolivia and Peru replacing the coca from Colombia, which was beginning to be seen as substandard quality than the coca from the neighboring countries. As demand for more and better cocaine increased, Escobar began working with Roberto Suárez Goméz, helping to further the product to other countries in the Americas and Europe, as well as being rumored to reach as far as Asia.

Palace of Justice siege

It is alleged that Escobar backed the 1985 storming of the Colombian Supreme Court by left-wing guerrillas from the 19th of April Movement, also known as M-19. The siege, which was done in retaliation for the Supreme Court studying the constitutionality of Colombia's extradition treaty with the U.S., resulted in the murders of half the judges on the court.[27] M-19 were paid to break into the Palace and burn all papers and files on Los Extraditables — a group of cocaine smugglers who were under threat of being extradited to the U.S. by the Colombian government. Escobar was listed as a part of Los Extraditables. Hostages were also taken for negotiation of their release, thus helping to prevent extradition of Los Extraditables to the U.S. for their crimes.[28]

Escobar at the height of his power

During the height of its operations, the Medellín Cartel brought in more than US $70 million per day (roughly $26 billion in a year). Smuggling 15 tons of cocaine per day, worth more than half a billion dollars, into the United States, the cartel spent over US $1000 per week purchasing rubber bands to wrap the stacks of cash, storing most of it in their warehouses. Ten percent (10%) of the cash had to be written off per year because of "spoilage", due to rats creeping in and nibbling on the bills they could reach.[18]

When questioned about the essence of the cocaine business, Escobar replied with "[the business is] simple: you bribe someone here, you bribe someone there, and you pay a friendly banker to help you bring the money back."[29] In 1989, Forbes magazine estimated Escobar to be one of 227 billionaires in the world with a personal net worth of close to US $3 billion[30] while his Medellín Cartel controlled 80% of the global cocaine market.[31] It is commonly believed that Escobar was the principal financier behind Medellín's Atlético Nacional, which won South America's most prestigious football tournament, the Copa Libertadores, in 1989.[32]

While seen as an enemy of the United States and Colombian governments, Escobar was a hero to many in Medellín (especially the poor people). He was a natural at public relations, and he worked to create goodwill among the poor of Colombia. A lifelong sports fan, he was credited with building football fields and multi-sports courts, as well as sponsoring children's football teams.[18] Escobar was also responsible for the construction of houses and football fields in western Colombia, which gained him popularity among the poor.[33][34][26] He worked hard to cultivate his Robin Hood image, and frequently distributed money through housing projects and other civic activities, which gained him notable popularity among the locals of the towns that he frequented. Some people from Medellín often helped Escobar avoid police capture by serving as lookouts, hiding information from authorities, or doing whatever else they could to protect him. At the height of his power, drug traffickers from Medellín and other areas were handing over between 20% and 35% of their Colombian cocaine-related profits to Escobar, as he was the one who shipped cocaine successfully to the United States.[35]

The Colombian cartels' continuing struggles to maintain supremacy resulted in Colombia quickly becoming the world's murder capital with 25,100 violent deaths in 1991 and 27,100 in 1992.[36] This increased murder rate was fueled by Escobar's giving money to his hitmen as a reward for killing police officers, over 600 of whom died as a result.[8]

La Catedral prison

After the assassination of Luis Carlos Galán, the administration of César Gaviria moved against Escobar and the drug cartels. Eventually, the government negotiated with Escobar and convinced him to surrender and cease all criminal activity in exchange for a reduced sentence and preferential treatment during his captivity. Declaring an end to a series of previous violent acts meant to pressure authorities and public opinion, Escobar surrendered to Colombian authorities in 1991. Before he gave himself up, the extradition of Colombian citizens to the United States had been prohibited by the newly approved Colombian Constitution of 1991. This act was controversial, as it was suspected that Escobar and other drug lords had influenced members of the Constituent Assembly in passing the law. Escobar was confined in what became his own luxurious private prison, La Catedral, which featured a football pitch, giant doll house, bar, jacuzzi and waterfall. Accounts of Escobar's continued criminal activities while in prison began to surface in the media, which prompted the government to attempt to move him to a more conventional jail on 22 July 1992. Escobar's influence allowed him to discover the plan in advance and make a well-timed escape, spending the rest of his life evading the police.[37][38]

Search Bloc and Los Pepes

Following Escobar's escape, the United States Joint Special Operations Command (consisting of members of DEVGRU (SEAL Team Six) and Delta Force) and Centra Spike joined the manhunt for Escobar. They trained and advised a special Colombian police task force known as the Search Bloc, which had been created to locate Escobar. Later, as the conflict between Escobar and the governments of the United States and Colombia dragged on, and as the numbers of Escobar's enemies grew, a vigilante group known as Los Pepes (Los Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar, "People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar") was formed. The group was financed by his rivals and former associates, including the Cali Cartel and right-wing paramilitaries led by Carlos Castaño, who would later fund the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá. Los Pepes carried out a bloody campaign, fueled by vengeance, in which more than 300 of Escobar's associates, his lawyer[39] and relatives were slain, and a large amount of the Medellín cartel's property was destroyed.

Members of the Search Bloc, and Colombian and United States intelligence agencies, in their efforts to find Escobar, either colluded with Los Pepes or moonlighted as both Search Bloc and Los Pepes simultaneously. This coordination was allegedly conducted mainly through the sharing of intelligence to allow Los Pepes to bring down Escobar and his few remaining allies, but there are reports that some individual Search Bloc members directly participated in missions of Los Pepes death squads.[34] One of the leaders of Los Pepes was Diego Murillo Bejarano (also known as "Don Berna"), a former Medellín Cartel associate who became a rival drug kingpin and eventually emerged as a leader of one of the most powerful factions within the Self-Defence of Colombia.

Personal life

Family and relationships

In March 1976, the 26-year-old Escobar married Maria Victoria Henao, who was 15. The relationship was discouraged by the Henao family, who considered Escobar socially inferior; the pair eloped.[19] They had two children: Juan Pablo (now Sebastián Marroquín) and Manuela.

In 2007, the journalist Virginia Vallejo published her memoir Amando a Pablo, odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar), in which she describes her romantic relationship with Escobar and the links of her lover with several presidents, Caribbean dictators, and high-profile politicians.[40] Her book inspired the movie Loving Pablo (2017).[41]

Drug distributor Griselda Blanco is also reported to have conducted a clandestine, but passionate, relationship with Escobar, with several items in her later-found diary linking him with the nicknames "Coque de Mi Rey" (My Coke King) and "Polla Blanca" (White Dick).[42]

Properties

After becoming wealthy, Escobar created or bought numerous residences and safe houses, with the Hacienda Nápoles gaining significant notoriety. The luxury house contained a colonial house, a sculpture park, and a complete zoo with animals from various continents, including elephants, exotic birds, giraffes, and hippopotamuses. Escobar had also planned to construct a Greek-style citadel near it, and though construction of the citadel was started, it was never finished.[43]

Escobar also owned a home in the US under his own name: a 6500 square foot, pink, waterfront mansion situated at 5860 North Bay Road in Miami Beach, Florida. The four-bedroom estate, built in 1948 on Biscayne Bay, was seized by the government in the 1980s. Later, the dilapidated property was owned by Christian de Berdouare, proprietor of the Chicken Kitchen fast-food chain, who had bought it in 2014. De Berdouare would later hire a documentary film crew and professional treasure hunters to search the edifice before and after demolition, for anything related to Escobar or his cartel. They would find unusual holes in floors and walls, as well as a safe that was stolen from its hole in the marble flooring before it could be properly examined.[44]

Escobar also owned a massive Caribbean getaway on Isla Grande, the largest of the cluster of the 27 coral cluster islands comprising Islas del Rosario, located about 22 miles (35 km) from Cartagena. The compound, now half-demolished and overtaken by vegetation and wild animals, featured a mansion, apartments, courtyards, a large swimming pool, a helicopter landing pad, reinforced windows, tiled floors, and a large, unfinished building to the side of the mansion.[45]

Death

16 months after his escape from La Catedral, Pablo Escobar died in a shootout on 2 December 1993, amid another of Escobar's attempts to elude the Search Bloc.[46] A Colombian electronic surveillance team, led by Brigadier Hugo Martínez,[47] used radio trilateration technology to track his radiotelephone transmissions and found him hiding in Los Olivos, a middle-class barrio in Medellín. With authorities closing in, a firefight with Escobar and his bodyguard, Álvaro de Jesús Agudelo (alias "El Limón"), ensued. The two fugitives attempted to escape by running across the roofs of adjoining houses to reach a back street, but both were shot and killed by Colombian National Police.[9] Escobar suffered gunshots to the leg and torso, and a fatal gunshot through the ear.

It has never been proven who actually fired the final shot into his ear, or determined whether this shot was made during the gunfight or as part of a possible execution, with wide speculation remaining regarding the subject. Some of Escobar's relatives believe that he had committed suicide.[10][48] His two brothers, Roberto Escobar and Fernando Sánchez Arellano, believe that he shot himself through the ear. In a statement regarding the topic, the duo stated that Pablo "had committed suicide, he did not get killed. During all the years they went after him, he would say to me every day that if he was really cornered without a way out, he would 'shoot himself through the ear'."[49]

Aftermath of his death

Soon after Escobar's death and the subsequent fragmentation of the Medellín Cartel, the cocaine market became dominated by the rival Cali Cartel until the mid-1990s when its leaders were either killed or captured by the Colombian government. The Robin Hood image that Escobar had cultivated maintained a lasting influence in Medellín. Many there, especially many of the city's poor whom Escobar had aided while he was alive, mourned his death, and over 25,000 people attended his funeral. Some of them consider him a saint and pray to him for receiving divine help.[50]

Virginia Vallejo's testimony

On July 4, 2006, Virginia Vallejo, the television anchorwoman who was romantically involved with Escobar from 1983 to 1987, offered to Colombian Attorney General, Mario Iguarán, her testimony in the trial against former Senator Alberto Santofimio, accused of conspiracy in the 1989 assassination of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán. Iguarán acknowledged that, although Vallejo had contacted his office on July 4, the judge had decided to close the trial on July 9, several weeks before the prospective closing date. The action was seen as too late.[51][52]

On July 18, 2006, Vallejo was taken to the United States on a special flight of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), for "safety and security reasons" due to her cooperation in high-profile criminal cases.[53][54] On July 24, a video in which Vallejo had accused Santofimio of instigating Escobar to eliminate presidential candidate Galán was aired by RCN Television of Colombia. The video was seen by 14 million people, and was instrumental for the reopened case of Galán’s assassination. On August 31, 2011 Santofimio was sentenced to 24 years in prison for his role in the crime.[55][56]

Role in the Palace of Justice siege

Among Escobar's biographers, only Vallejo has given a detailed explanation of his role in the 1985 Palace of Justice siege. The journalist stated that Escobar had financed the operation, which was committed by M-19; but she blamed the army for the killings of more than 100 people, including 11 Supreme Court magistrates, M-19 members, and employees of the cafeteria. Her statements prompted the reopening of the case in 2008; Vallejo was asked to testify, and many of the events she had described in her book and testimonial were confirmed by the Colombia's Commission of Truth.[57][58] These events led to further investigation into the siege that resulted with the conviction of a high-ranking former colonel and a former general, later sentenced to 30 and 35 years in prison, respectively, for the forced disappearance of the detained after the siege.[59][60] Vallejo would subsequently testify in Galán's assassination.[61] In her book, Amando a Pablo, odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar), she had accused several politicians, including Colombian presidents Alfonso López Michelsen, Ernesto Samper and Álvaro Uribe of having links to drug cartels.[62] Due to threats, and her cooperation in these cases, on June 3, 2010 the United States granted political asylum to the Colombian journalist.

Relatives

Escobar's widow (María Henao, now María Isabel Santos Caballero), son (Juan Pablo, now Juan Sebastián Marroquín Santos) and daughter (Manuela) fled Colombia in 1995 after failing to find a country that would grant them asylum.[63] Despite Escobar's numerous and continual infidelities, Maria remained supportive of her husband, though she urged him to eschew violence. Members of the Cali Cartel even replayed their recordings of her conversations with Pablo for their wives to demonstrate how a woman should behave.[64] This attitude proved to be the reason the cartel did not kill her and her children after Pablo's death, although the group demanded (and received) millions of dollars in reparations for Escobar's war against them. Henao even successfully negotiated for her son's life by personally guaranteeing he would not seek revenge against the cartel or participate in the drug trade.[65]

After escaping first to Mozambique, then to Brazil, the family settled in Argentina.[66] Living under her assumed name, Henao became a successful real estate entrepreneur until one of her business associates discovered her true identity, and Henao absconded with her earnings. Local media were alerted, and after being exposed as Escobar's widow, Henao was imprisoned for eighteen months while her finances were investigated. Ultimately, authorities were unable to link her funds to illegal activity, and she was released.[67] According to her son, Henao fell in love with Escobar "because of his naughty smile [and] the way he looked at [her]. [He] was affectionate and sweet. A great lover. I fell in love with his desire to help people and his compassion for their hardship. We [would] drive to places where he dreamed of building schools for the poor. From [the] beginning, he was always a gentleman."[68] Henao is now believed to be living under an alias in North Carolina. This is completely false: María Victoria Henao de Escobar, with her new identity as María Isabel Santos Caballero, continues to live in Buenos Aires with her son and daughter.[69] On June 5, 2018, the Argentine federal judge Nestor Barral accused her and his son, Sebastián Marroquín Santos, of money laundering with two Colombian drug traffickers.[70][71][72] The judge ordered the seizing of assets for about $1m each.[73]

Argentinian filmmaker Nicolas Entel's documentary Sins of My Father (2009) chronicles Marroquín's efforts to seek forgiveness, on behalf of his father, from the sons of Rodrigo Lara, Colombia's justice minister who was assassinated in 1984, as well as from the sons of Luis Carlos Galán, the presidential candidate who was assassinated in 1989. The film was shown at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and premiered in the US on HBO in October 2010.[74] In 2014, Marroquín published Pablo Escobar, My Father under his birth name. The book provides a firsthand insight into details of his father's life and describes the fundamentally disintegrating effect of his death upon the family. Marroquín aimed to publish the book in hopes to resolve any inaccuracies regarding his father's excursions during the 1990s.[75]

Escobar's sister, Luz Maria Escobar, also made multiple gestures in attempts to make amends for the drug baron's crimes. These include making public statements in the press, leaving letters on the graves of his victims and on the 20th anniversary of his death, organizing a public memorial for Escobar's victims.[76] Escobar's body was exhumed on 28 October 2006, at the request of some of his relatives in order to take a DNA sample to confirm the alleged paternity of an illegitimate child and remove all doubt about the identity of the body that had been buried next to his parents for 12 years.[77] A video of the exhumation was broadcast by RCN, angering Marroquín, who accused his uncle, Roberto Escobar, and cousin, Nicolas Escobar, of being "merchants of death" by allowing for the video to air.[78]

Hacienda Nápoles

After Escobar's death, the ranch, zoo and citadel at Hacienda Nápoles were given by the government to low-income families under a law called Extinción de Dominio (Domain Extinction). The property has been converted into a theme park surrounded by four luxury hotels overlooking the zoo.[43]

Escobar Inc

In 2014, Roberto Escobar founded Escobar Inc with Olof K. Gustafsson and registered Successor-In-Interest rights for his brother Pablo Escobar in California, United States.[79]

In popular culture

Books

Escobar has been the subject of several books, including the following:

- Escobar (2010), by Roberto Escobar, written by his brother is shows how he became infamous and ultimately died.[80]

- Escobar Gaviria, Roberto (2016). My Brother - Pablo Escobar. Escobar, Inc. ISBN 978-0692706374.

- Kings of Cocaine (1989), by Guy Gugliotta, retells the history and operations of the Medellín Cartel, and Escobar's role within it.[81]

- Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw (2001), by Mark Bowden,[82][83] relates how Escobar was killed and his cartel dismantled by US special forces and intelligence, the Colombian military, and Los Pepes.[84]

- Pablo Escobar: My Father (2016), by Juan Pablo Escobar, translated by Andrea Rosenberg .[85]

- Pablo Escobar: Beyond Narcos (2016), by Shaun Attwood, tells the story of Pablo and the Medellin Cartel in the context of the failed War on Drugs; ISBN 978-1537296302

- American Made: Who Killed Barry Seal? Pablo Escobar or George HW Bush (2016), by Shaun Attwood, tells Pablo's story as a suspect in the murder of CIA pilot Barry Seal; ISBN 978-1537637198

- Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar (2017) by Virginia Vallejo, originally published by Penguin Random House in Spanish in 2007, and later translated to 16 languages.

Films

Two major feature films on Escobar, Escobar (2009) and Killing Pablo (2011), were announced in 2007.[86] Details about them, and additional films about Escobar, are listed below.

- Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke (2007) is a TV movie documentary by National Geographic, featuring archival footage and commentary by stakeholders.[87][88]

- Escobar (2009) was delayed because of producer Oliver Stone's involvement with the George W. Bush biopic W. (2008). As of 2008, the release date of Escobar remained unconfirmed..[89] Regarding the film, Stone said: "This is a great project about a fascinating man who took on the system. I think I have to thank Scarface, and maybe even Ari Gold."[90]

- Killing Pablo (2011), was supposedly in development for several years, directed by Joe Carnahan. It was to be based on Mark Bowden's 2001 book of the same title, which in turn was based on his 31-part Philadelphia Inquirer series of articles on the subject.[83][84] The cast was reported to include Christian Bale as Major Steve Jacoby and Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez as Escobar.[91][92] In December 2008, Bob Yari, producer of Killing Pablo, filed for bankruptcy.[93]

- Escobar: Paradise Lost: a romantic thriller in which a naive Canadian surfer falls in love with a girl who turns out to be Escobar's niece.

- Loving Pablo: a 2017 Spanish film based on Virginia Vallejo's book Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar with Javier Bardem as Escobar, and Penélope Cruz as Virginia Vallejo.[94]

- American Made, a 2017 American biographical film based on Barry Seal; Escobar was portrayed by Mauricio Mejía.[95]

Television

- In the 2007 HBO television series, Entourage, actor Vincent Chase (played by Adrian Grenier) is cast as Escobar in a fictional film entitled Medellín.[96]

- A Netflix original television series depicting the story of Escobar, titled Narcos, was released on 28 August 2015, starring Brazilian actor Wagner Moura as Pablo.[97] Season two premiered on the streaming service on 2 September 2016.[98]

- Caracol TV produced a television series, Pablo Escobar: El Patrón del Mal (Pablo Escobar, The Boss Of Evil), which began airing on 28 May 2012, and stars Andrés Parra as Pablo Escobar. It is based on Alonso Salazar's book La parábola de Pablo.[99]

- One of ESPN's 30 for 30 series films, The Two Escobars (2010), by directors Jeff and Michael Zimbalist, looks back at Colombia's World Cup run in 1994 and the relationship between sports and the country's criminal gangs — notably the Medellín narcotics cartel run by Escobar. The other Escobar in the film title refers to former Colombian defender Andrés Escobar (no relation to Pablo), who was shot and killed one month after conceding an own goal that contributed to the elimination of the Colombian national team from the 1994 FIFA World Cup.[100]

- National Geographic in 2016 broadcast a biography series Facing that included an episode featuring Escobar.[101]

- In 2005, Court TV (now TruTV) crime documentary series Mugshots released an episode on Escobar titled "Pablo Escobar – Hunting The Druglord".[102]

References and notes

- ↑ David Hutt (25 September 2014). "Heroes and Villains: Pablo Escobar". Archived from the original on 3 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Pablo Escobar Gaviria – English Biography – Articles and Notes". ColombiaLink.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "Pablo Emilio Escobar 1949 – 1993 9 Billion USD – The business of crime – 5 'success' stories". MSN. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "10 facts reveal the absurdity of Pablo Escobar's wealth". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ "Here's How Rich Pablo Escobar Would Be If He Was Alive Today". UNILAD. 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ "10 facts reveal the absurdity of Pablo Escobar's wealth". businessinsider.com. February 2016.

- 1 2 Page 469, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- 1 2 Karl Penhaul (9 May 2003). "Drug kingpin's killer seeks Colombia office". Boston Globe.

- 1 2 "Decline of the Medellín Cartel and the Rise of the Cali Mafia". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Familiares exhumaron cadáver de Pablo Escobar para verificar plenamente su identidad". El Tiempo.

- ↑ "Abel de Jesús Escobar Echeverri". Geni.

- ↑ "Hermilda Gaviria Berrío". Geni.

- ↑ Marcela Grajales. "Pablo Escobar". Accents Magazine. Kean University. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Escobar Seventh Richest Man in the World in 1990". Richest Person.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Salazar, Alonso. "Pablo Escobar, h el patrón del mal (La parábola de Pablo)". Google Livres. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial USA, 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ↑ J.D. Rockefeller (17 March 2016). Cocaine King Pablo Escobar: Crimes and Drug Dealings. J.D. Rockefeller. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-5306-1889-7.

- ↑ "Colombian Druglord Trying To Turn Wealth Into Respect". Orlando Sentinel. 10 March 1991. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Escobar, Roberto (2009). The Accountant's Story: Inside the Violent World of the Medellín Cartel. Grand Central Publishing.

- 1 2 Page 74, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ "Pablo Escobar – The Medellin Cartel". Medellintraveler.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "Amazing story of how Pablo Escobar came to be the richest crook in history". Daily Record. Scotland. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "The godfather of cocaine". Frontline. WGBH.

- ↑ Baselmans 2016, p. 88.

- ↑ Page 116, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. "SANTOFIMIO RECOMENDÓ MATAR A LUIS CARLOS GALÁN: POPEYE". El Tiempo.

- 1 2 J.D. Rockefeller 2016, p. 5.

- ↑ "Cali Colombia nacional Pablo Escobar financió la toma del Palacio de Justicia Escobar financió toma del Palacio de Justicia". El Pais.

- ↑ Jhon Jairo Velásquez (obtained 21 October 2014)

- ↑ "Farmer's son who bribed and murdered his way into drugs: Neither government forces nor other drug traffickers were interested in taking Pablo Escobar alive. Patrick Cockburn reports". The Independent. London. 3 December 1993.

- ↑ "Japan's Tsutsumi Still Tops Forbes' Richest List". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 10 July 1989. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Meade, Teresa A. (2008). A history of modern Latin America, 1800 – 2000. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 302. ISBN 1-4051-2050-9. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ↑ Davison, Phil. "The Road to Italy: In the Shadow of the Drug Barons". The Independent 20 May 1990. Lexis-Nexis Academic. 8 October 2009

- ↑ "GARCÍA HERREROS CAUSA CONFUSIÓN". El Tiempo.

- 1 2 Mark Bowden (2001). Killing Pablo: The Hunt For The World's Greatest Outlaw. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- ↑ Baselmans 2016, p. 97.

- ↑ "Colombia 1993 Chapter II: The Violence Phenomenon". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ↑ Treaster, Joseph B. (23 July 1992). "Colombian Drug Baron Escapes Luxurious Prison After Gunfight". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ↑ "Escobar escape humiliates Colombian leaders".

- ↑ "Angry Over Blast, Colombia Vigilantes Kill Escobar Lawyer". "Angry Over Blast, Colombia Vigilantes Kill Escobar Lawyer". Los Angeles Times, 17 April 1993

- ↑ "Los Narcopresidentes" [The Narco-presidents] (in Spanish). 24 November 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ↑ Mayorga, Emilio (September 3, 2017). "Loving Pablo Director on Reuniting Javier Bardem and Penelope Cruz: It's Been Very Intense". Variety. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ↑ Jerry, Tom (30 September 2013). "Me matan, Limon! -Patricio Rey y sus Redonditos de Ricota". INEDITO. Retrieved 19 June 2016 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 Ceaser, Mike (2 June 2008). "At home on Pablo Escobar's ranch". BBC News. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Macias, Amanda Macias & Associated Press (24 January 2016). "Military & Defense: A luxurious Miami mansion built by the 'King of Cocaine' is no more". Business Insider.

- ↑ Macias, Amanda (12 May 2016). "Military & Defense: This dilapidated villa once served as a Caribbean getaway for drug-kingpin Pablo Escobar". Business Insider.

- ↑ "Colombia Drug Lord Escobar Dies in Shootout". LA Times, 3 December 1993

- ↑ Interview with Hugo Martinez – the man who 'got' Pablo Escobar D. Streatfeild. November 2000.

- ↑ Video of Escobar's exhumation on YouTube (in Spanish)

- ↑ Roberts, Kenneth. (2007). Zero Hour: Killing of the Cocaine King.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-25183649

- ↑ "Colombian Attorney General on Virginia Vallejo's offer to testify against Santofimio" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2010.

- ↑ "Back to jail for Colombia ex-minister". Independent Online. Bogotá. September 1, 2011. Retrieved 2017-10-19.

- ↑ "Virginia Vallejo takes refuge in United States". Virginia Vallejo. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. reprinted and translated from Gonzalo Guillen (16 July 2006). "Virginia Vallejo". El Nuevo Herald.

- ↑ "Pablo Escobar's Ex-Lover Flees Colombia". Fox News Channel.

- ↑ "Testimony of Virginia Vallejo in 2006".

- ↑ "Links of Colombian politicians with drug cartels".

- ↑ Caracol Radio (27 August 2008). "Virginia Vallejo testificó en el caso Palacio de Justicia". Caracol Radio.

- ↑ Michael Evans (17 December 2009). "Truth Commission Blames Colombian State for Palace of Justice Tragedy". UNREDACTED.

- ↑ "Colombia ex-officer jailed after historic conviction". BBC News.

- ↑ "Colombian 1985 Supreme Court raid commander sentenced". BBC News.

- ↑ "Galan Slaying a State Crime, Colombian Prosecutors Say". Latin American Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Romero, Simon (3 October 2007). "Colombian Leader Disputes Claim of Tie to Cocaine Kingpin". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ↑ "Drug lord's wife and son arrested". BBC News. 17 November 1999. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Page 466, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ Pages 468-495, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ King, Julie (15 June 2015). "A Cursed Family: A Look at Pablo Escobar's Family 21 Years After His Death". XPat Nation. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Pages 521-537, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ Page 68, Pablo Escobar, My Father. Escobar, Juan Pablo. St. Martin's Press, New York. 2014.

- ↑ "Se conoce foto de la hija de Pablo Escobar en Buenos Aires". El Tiempo. April 25, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Pablo Escobar's widow and son in Argentina money laundering probe". Deutsche Welle. November 1, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ↑ "María Isabel Santos Cabllero and Sebastián Marroquín held on money laundering charges".

- ↑ Lam, Katherine (June 6, 2018). "Pablo Escobar's widow, son charged with money laundering in Argentina". Fox News. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Pablo Escobar's widow and son held on money laundering charges in Argentina". The Guardian. June 5, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Drug lord's son seeks forgiveness". CNN. 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Shepherd, Jack (12 September 2016). "Narcos season 2: Pablo Escobar's son labels Netflix show 'insulting', lists 28 historical errors". Independent.

- ↑ Alexander, Harriet (3 December 2014). "Pablo Escobar's sister trying to pay for the sins of her brother (Luz Maria Escobar), the sister of Colombian cartel boss Pablo Escobar, has told how she is trying to make amends for her murderous brother". The Telegraph.

- ↑ "Familiares exhumaron cadáver de Pablo Escobar para verificar plenamente su identidad". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ↑ "La exhumación de Pablo". Semana (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ↑ "California Business Portal: Successor-In-Interest". 28 April 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Escobar, Roberto (2010). Escobar. Hodder Paperbacks.

- ↑ McAleese, Peter (1993). No Mean Soldier. Cassell Pub.

- ↑ Bowden, Mark (2002). Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw. Penguin Pub.

- 1 2 McNary, Dave (1 October 2007). "Yari fast-tracking Escobar biopic". Variety. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- 1 2 "What is actor Christian Bale doing next?". Journal Now. 25 December 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Escobar, Juan Pablo (2016). Pablo Escobar: My Father. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9781250104625.

- ↑ "Weekly Screengrab: Sparring Partners". TribecaFilmFestival.org. 1 October 2007.

- ↑ Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke. National Geographic. 2007. (Amazon)

- ↑ Pablo Escobar: The King of Coke. National Geographic. 2007. (La Peliculas)

- ↑ "No Bardem for Killing Pablo". WhatCulture. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (8 October 2007). "Stone to produce another 'Escobar'". Variety. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ↑ "Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez to Play PABLO ESCOBAR". Poor But Happy. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- ↑ Faraci, Devin (14 August 2008). "Joe Carnahan Is Going to Be Killing a New Pablo, and We Know Who It Is". Chud. Archived from the original on 15 August 2008.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (12 December 2008). "Bob Yari crashes into Chapter 11". Variety.

- ↑ Vivarelli, Nick (2017-09-11). "Javier Bardem on Playing Pablo Escobar With Penelope Cruz in Loving Pablo". Variety. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ↑ "'American Made': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 29 September 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ↑ Barius, Claudette (18 June 2007). "Entourage: The making of Medellín". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ Shepherd, Jack (28 July 2015). "New on Netflix August 2015: From Narcos and Spellbound to Kick Ass 2 and Dinotrux". The Independent. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ Strause, Jackie (2 September 2016). "'Narcos' Season 2: Episode-by-Episode Binge-Watching Guide". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ "Telemundo Media's 'Pablo Escobar, El Patron del Mal' Averages Nearly 2.2 Million Total Viewersby zap2it.com". TV by the Numbers. Zap2It. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Two Escobars". the2escobars.com.

- ↑ Sang, Lucia I. Suarez (30 August 2016). "Ex-DEA agents who fought Pablo Escobar headline new NatGeo documentary". Fox News. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ "Mugshots | Pablo Escobar – Hunting the Druglord". snagfilms.com. 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

This episode follows Escobar on his journey to becoming the Columbian Godfather.

References

- J.D. Rockefeller (2016). The Life and Crimes of Pablo Escobar. J.D. Rockefeller. GGKEY:76EJNZLQU6L.

- John, Baselmans (2016). DRUGS. [S.l.]: LULU COM. ISBN 9781326843250. OCLC 982503721.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pablo Escobar. |

- "The Abandoned House of Pablo Escobar". noaccess.eu.