North Sentinel Island

2009 NASA image of North Sentinel Island; the island's protective fringe of coral reefs can be seen clearly. | |

North Sentinel Island Location of North Sentinel Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Bay of Bengal |

| Coordinates | 11°33′25″N 92°14′28″E / 11.557°N 92.241°ECoordinates: 11°33′25″N 92°14′28″E / 11.557°N 92.241°E [1] |

| Archipelago | Andaman Islands[2] |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Bay of Bengal |

| Total islands | 5 |

| Major islands |

|

| Area | 59.67 km2 (23.04 sq mi)[3] |

| Length | 7.8 km (4.85 mi) |

| Width | 7.0 km (4.35 mi) |

| Coastline | 31.6 km (19.64 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 122 m (400 ft)[4] |

| Administration | |

| Union territory | Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

| District | South Andaman |

| Tehsil | Port Blair Tehsil[5] |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | North Sentinelese |

| Population |

40[5] (2011) (census estimate, actual population highly uncertain) May be as high as 400 |

| Population rank | -1 |

| Ethnic groups | Sentinelese[2] |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| PIN | 744202[6] |

| ISO code | IN-AN-00[7] |

| Official website |

www |

| Avg. summer temperature | 30.2 °C (86.4 °F) |

| Avg. winter temperature | 23.0 °C (73.4 °F) |

| Census Code | 35.639.0004 |

North Sentinel Island is one of the Andaman Islands, which includes South Sentinel Island, in the Bay of Bengal. It is home to the Sentinelese who, often violently, reject any contact with the outside world, and are among the last people worldwide to remain virtually untouched by modern civilization. As such, only limited information about the island is known.

Nominally, the island belongs to the South Andaman administrative district, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[8] In practice, Indian authorities recognise the islanders' desire to be left alone and restrict their role to remote monitoring, even allowing them to kill non-Sentinelese people without prosecution.[9][10] Thus the island can be considered a sovereign area under Indian protection.

Geography

North Sentinel lies 36 kilometres (22 mi) west of the town of Wandoor in South Andaman Island,[2] 50 km (31 mi) west of Port Blair, and 59.6 kilometres (37.0 mi) north of its counterpart South Sentinel Island. It has an area of about 59.67 km2 (23.04 sq mi) and a roughly square outline.[11]

North Sentinel is surrounded by coral reefs, and lacks natural harbours. The entire island, other than the reefs, is forested.[12] There is a narrow beach encircling the island, behind which the ground rises 20 m (66 ft), and then gradually to between 46 m (150 ft)[13]:257 and 122 m (400 ft)[1] near the centre. Reefs extend around the island to between 800 and 1,290 metres (0.5–0.8 mi) from the shore.[1] A forested islet, Constance Island, also "Constance Islet",[1] is located about 600 metres (2,000 ft) off the southeast coastline, at the edge of the reef.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake tilted the tectonic plate under the island, lifting it by 1 to 2 metres (3 to 7 ft). Large tracts of the surrounding coral reefs were exposed and became permanently dry land or shallow lagoons, extending all the island's boundaries – by as much as 1 kilometre (3,300 ft) on the west and south sides – and uniting Constance Islet with the main island.[14]:347[15]

History

The Onge, one of the other indigenous peoples of the Andamans, were aware of North Sentinel Island's existence and their traditional name for it is Chia daaKwokweyeh.[2][14]:362–363 They also have strong cultural similarities with what little has been remotely observed amongst the Sentinelese. However, Onge who were brought there by the British during the 19th century could not understand the language, so a significant period of separation is likely.[2][14]:362–363

Chola dynasty

Rajendra Chola I (1014 - 1044), one of the Tamil Chola dynasty kings, conquered the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to use them as a strategic naval base to launch a naval expedition against the Sriwijaya Empire (a Buddhist empire based in the island of Sumatra, Indonesia). They called the islands Tinmaittivu ("Valour/Truth/Strength islands" in Tamil).[16]

Maratha empire

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a whole provided a temporary maritime base for ships of the Maratha Empire in the 17th century. The Maratha navy's admiral Kanhoji Angre established naval supremacy with a base in the islands and is credited with attaching those islands to India.[17][18][19][20]

British visits

British surveyor John Ritchie, observed "a multitude of lights" from an East India Company hydrographic survey vessel, the Diligent, as it passed by the island in 1771.[2][14]:362–363[21] Homfray, an administrator, travelled to the island in March 1867.[22]:288

Toward the end of the same year's summer monsoon season, the Nineveh, an Indian merchant ship, was wrecked on a reef near the island. The 106 surviving passengers and crewmen landed on the beach in the ship's boat and fended off attacks by the Sentinelese. They were eventually found by a Royal Navy rescue party.[14]:362–363

An expedition led by Maurice Vidal Portman, a government administrator who hoped to research the natives and their customs, accomplished a successful landing on North Sentinel Island in January 1880. The group found a network of pathways and several small, abandoned villages. After several days, six Sentinelese (an elderly couple and four children) were captured and taken to Port Blair. The colonial officer in charge of the operation wrote that the entire group, "sickened rapidly, and the old man and his wife died, so the four children were sent back to their home with quantities of presents".[2][21][22]:288 A second landing was made by Portman on 27 August 1883 after the eruption of Krakatoa was mistaken for gunfire and interpreted as the distress signal of a ship. A search party landed on the island and left gifts before returning to Port Blair.[2][22]:288 Portman visited the island several more times between January 1885 and January 1887.[22]:288

Modern period

Indian exploratory parties under orders to establish friendly relations with the Sentinelese made brief landings on the island every few years beginning in 1967.[2] In 1975, Leopold III of Belgium, on a tour of the Andamans, was brought by local dignitaries for an overnight cruise to the waters off North Sentinel Island.[21] The cargo ship MV Rusley ran aground on coastal reefs in mid-1977, and the MV Primrose did so in August 1981. The Sentinelese are known to have scavenged both wrecks for iron. Settlers from Port Blair also visited the sites to recover the cargo. In 1991, salvage operators were authorized to dismantle the ships.[14]:342

After the Primrose grounded on the North Sentinel Island reef on 2 August 1981, crewmen several days later noticed that some men carrying spears and arrows were building boats on the beach. The captain of Primrose radioed for an urgent drop of firearms so his crew could defend themselves. They did not receive any because a large storm stopped other ships from reaching them. However, the heavy seas also prevented the islanders from approaching the ship. One week later, the crewmen were rescued by a helicopter under contract to the Indian Oil And Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC).[23].

The first peaceful contact with the Sentinelese was made by Triloknath Pandit, a director of the Anthropological Survey of India, and his colleagues on 4 January 1991.[22]:289[24] Indian visits to the island ceased in 1997.[2]

The Sentinelese survived the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and its after-effects, including the tsunami and the uplifting of the island. Three days after the earthquake, an Indian government helicopter observed several islanders, who shot arrows and threw stones at the hovering aircraft.[2][14]:362–363[25] Although the tsunami disturbed the fishing grounds, the Sentinelese appear to have adapted.[15]

On 26 January 2006, two fishermen, Sunder Raj, age 48, and Pandit Tiwari, age 52, were killed by Sentinelese when their boat accidentally drifted too close to the island when they were fishing for mud crabs. The Indian government did not seek to prosecute the deaths.[9]

Since then, there has been no contact between the Sentinelese and the rest of the world, and a 3-mile exclusion zone has been established around the island.

Demographics

North Sentinel Island is inhabited by a group of indigenous people, the Sentinelese. Their population is estimated at between 50 and 400 individuals.[2] They reject any contact with other people, and are among the last people to remain virtually untouched by modern civilization.[21]

The population faces the potential threats of infectious diseases to which they have no immunity, as well as violence from intruders. The Indian government has declared the entire island and its surrounding waters extending 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometres) from the island to be an exclusion zone.[26] At the 2011 census, the India surveyors counted 15 natives on the shore of the island.[27]

| Census | Population estimate[5] |

|---|---|

| 1901 | 117 |

| 1911 | 117 |

| 1921 | 117 |

| 1931 | 50 |

| 1961 | 50 |

| 1991 | 23 |

| 2001 | 39 |

| 2011 | 40 |

Political status

The Andaman and Nicobar Administration stated in 2005 that they have no intention to interfere with the lifestyle or habitat of the Sentinelese and are not interested in pursuing any further contact with them or enforcing law on the island.[28] Although North Sentinel Island is not legally an autonomous administrative division of India, scholars have referred to it and its people as effectively autonomous,[29][30] or "independent".[29][31]

Image gallery

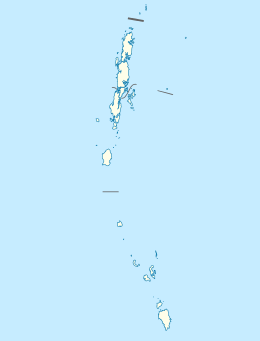

Outline map of the Andaman Islands, with the location of North Sentinel Island highlighted (in red).

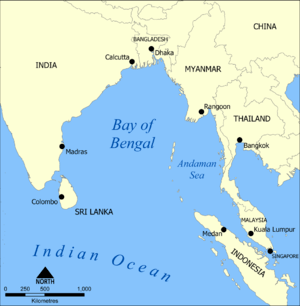

Outline map of the Andaman Islands, with the location of North Sentinel Island highlighted (in red). Bay of Bengal, with Andaman Islands south of Myanmar

Bay of Bengal, with Andaman Islands south of Myanmar Map of the island

Map of the island

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "The Andaman Islands and the Nicobar Islands § 9.8 North Sentinel Island". Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal (PDF). Sailing Directions (Enroute). Pub. 173 (8th ed.). Springfield, Virginia: National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2014. p. 266. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Weber, George. "Chapter 8: The Tribes; Part 6. The Sentineli". The Andamanese. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- ↑ "Forest Statistics" (PDF). Department of Environment & Forests Andaman & Nicobar Islands. p. 7. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ↑ pro star

- 1 2 3 Andaman and Nicobar Islands Census 2011

- ↑ "A&N Islands - Pincodes". 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Registration Plate Numbers added to ISO Code

- ↑ "Village Code Directory: Andaman & Nicobar Islands" (PDF). Census of India. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- 1 2 Foster, Peter (8 February 2006). "Stone Age tribe kills fishermen who strayed onto island". The Telegraph. London, UK.

- ↑ Bonnett, Alastair: Off The Map, page 82. Carreg Aurum Press, 2014

- ↑ http://ls1.and.nic.in/doef/WebPages/ForestStatistics2013.pdf

- ↑ Weber, George. "Chapter 2: They Call it Home". The Andamanese. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "North Sentinel". The Bay of Bengal Pilot. Admiralty. London: United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. 1887. p. 257. OCLC 557988334.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pandya, Vishvajit (2009). In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858–2006). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4272-9. LCCN 2008943457. OCLC 371672686. OL 16952992W.

- 1 2 Weber, George (2009). "The 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami". Archived from the original on 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Government of India (1908). "The Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Local Gazetteer". Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta.

... In the great Tanjore inscription of 1050 AD, the Andamans are mentioned under a translated name along with the Nicobars, as Nakkavaram or land of the naked people.

- ↑ Dr. Sidda Goud; Manisha Mookherjee (28 February 2015). CHINA IN INDIAN OCEAN REGION. Allied Publishers. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-81-8424-977-4.

- ↑ Prakash Chander (1 January 2003). India: Past and Present. APH Publishing. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-81-7648-455-8.

- ↑ Dr Saji Abraham (1 August 2015). China's Role in the Indian Ocean: Its Implications on India's National Security. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-93-84464-71-4.

- ↑ Bharat Verma (1 September 2013). Indian Defence Review 28. 1: Jan-Mar 2013. Lancer Publishers. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-81-7062-183-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Goodheart, Adam (Autumn 2000). "The Last Island of the Savages". American Scholar. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sarkar, Jayanta (1997). "Befriending the Sentinelese of the Andamans: A Dilemma". In Pfeffer, Georg; Behera, Deepak Kumar. Development Issues, Transition and Change. Contemporary Society: Tribal Studies. 2. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-642-2. LCCN 97905535. OCLC 37770121. OL 324654M.

- ↑ "The strange mystery of North Sentinel Island". Unexplained MYSTERIES. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ McGirk, Tim (10 January 1993). "Islanders running out of isolation: Tim McGirk in the Andaman Islands reports on the fate of the Sentinelese". The Independent. London, UK.

- ↑ Buncombe, Andrew (6 February 2010). "With one last breath, a people and language are gone". The New Zealand Herald. The Independent. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ number23 (8 May 2015). "The Island Tribe Hostile To Outsiders Face Survival Threat". AnonHQ.com. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ↑ census, archive.org; accessed 2 April 2017.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Subir (5 March 2005). "Extinction threat for Andaman natives".

- 1 2 Dr. V.R. Rao, Tsunami in South Asia: Studies of Impact on Communities of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Allied Publishers Private Limited, 2007, chapter 8.

- ↑ Claire Wintle, Colonial Collecting and Display, Berghahn Books, 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Ed. Aruna Ghose et al, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: India, 2014, p. 627.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to North Sentinel Island. |

- Geological Survey of India

- The Sentinelese People - history of the Sentinelese and of the island

- Brief factsheet about the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands by the Andaman & Nicobar Administration (archived 10 April 2009)

- "The Andaman Tribes: Victims of Development"

- Video clip from Survival International

- Photographs of the 1981 Primrose rescue