Nipah virus infection

| Nipah virus infection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Structure of a Henipavirus | |

| Specialty |

Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | None, fever, cough, headache, confusion[1] |

| Complications | Inflammation of the brain, seizures[2] |

| Usual onset | 5 to 14 days after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Nipah virus (spread by direct contact)[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, confirmed by laboratory testing[4] |

| Prevention | Avoiding exposure to bats and sick pigs, not drinking raw date palm sap[5] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[2] |

| Frequency | ~700 human cases (1998 to May 2018)[6][7] |

| Deaths | ~50 to 75% risk of death[6][8] |

Nipah virus infection (NiV) is a viral infection caused by the Nipah virus.[2] Symptoms from infection vary from none to fever, cough, headache, shortness of breath, and confusion.[1][2] This may worsen into a coma over a day or two.[1] Complications can include inflammation of the brain and seizures following recovery.[2]

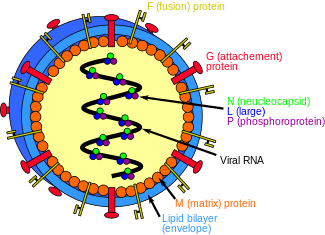

The Nipah virus is a type of RNA virus in the genus Henipavirus.[2] It can both spread between people and from other animals to people.[2] Spread typically requires direct contact with an infected source.[3] The virus normally circulates among specific types of fruit bats.[2] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and confirmed by laboratory testing.[4]

Management involves supportive care.[2] As of 2018 there is no vaccine or specific treatment.[2] Prevention is by avoiding exposure to bats and sick pigs and not drinking raw date palm sap.[5] As of May 2018 about 700 human cases of Nipah virus are estimated to have occurred and 50 to 75 percent of those who were infected died.[6][8][7] In May 2018, an outbreak of the disease resulted in at least 17 deaths in the Indian state of Kerala.[9][10][11]

The disease was first identified in 1998 during an outbreak in Malaysia while the virus was isolated in 1999.[2][12] It is named after a village in Malaysia, Sungai Nipah.[12] Pigs may also be infected and millions were killed in 1999 to stop the spread of disease.[2][12]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms start to appear after 5–14 days from exposure.[12] Initial symptoms are fever, headache, drowsiness followed by disorientation and mental confusion. These symptoms can progress into coma as fast as in 24–48 hours. Encephalitis, inflammation of the brain, is a potentially fatal complication of Nipah virus infection. Respiratory illness can also be present during the early part of the illness.[12] Nipah-case patients who had breathing difficulty are more likely than those without respiratory illness to transmit the virus.[13] The disease is suspected in symptomatic individuals in the context of an epidemic outbreak.

Risks

The risk of exposure is high for hospital workers and caretakers of those infected with the virus. In Malaysia and Singapore, Nipah virus infection occurred in those with close contact to infected pigs. In Bangladesh and India, the disease has been linked to consumption of raw date palm sap (toddy) and contact with bats.[14]

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of Nipah virus infection is made using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from throat swabs, cerebrospinal fluid, urine and blood analysis during acute and convalescent stages of the disease. IgG and IgM antibody detection can be done after recovery to confirm Nipah virus infection. Immunohistochemistry on tissues collected during autopsy also confirms the disease.[12] Viral RNA can be isolated from the saliva of infected persons.

Prevention

Prevention of Nipah virus infection is important since there is no effective treatment for the disease. The infection can be prevented by avoiding exposure to bats in endemic areas and sick pigs. Drinking of raw palm sap (palm toddy) contaminated by bat excrete,[15] eating of fruits partially consumed by bats and using water from wells infested by bats [16] should be avoided. Bats are known to drink toddy that is collected in open containers, and occasionally urinate in it, which makes it contaminated with the virus.[15] Surveillance and awareness are important for preventing future outbreaks. The association of this disease within reproductive cycle of bats is not well studied. Standard infection control practices should be enforced to prevent nosocomial infections. A subunit vaccine using the Hendra G protein was found to produce cross-protective antibodies against henipavirus and nipavirus has been used in monkeys to protect against Hendra virus, although its potential for use in humans has not been studied.[17]

Treatment

Currently there is no effective treatment for Nipah virus infection. The treatment is limited to supportive care. It is important to practice standard infection control practices and proper barrier nursing techniques to avoid the spread of the infection from person to person. All suspected cases of Nipah virus infection should be isolated.

Ribavirin has been studied in a small number of people, however whether or not it is useful is unclear as of 2011.[18] Passive immunization using a human monoclonal antibody that targets the Nipah G glycoprotein has been evaluated in the ferret model as post-exposure prophylaxis.[6][12] The anti-malarial drug chloroquine was shown to block the critical functions needed for maturation of Nipah virus, although no clinical benefit has yet been observed.[19] m102.4, a human monoclonal antibody, has been used in people on a compassionate use basis in Australia and was in pre-clinical development in 2013.[6]

Outbreaks

Nipah virus outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh and India. The highest mortality due to Nipah virus infection has occurred in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, the outbreaks are typically seen in winter season.[20] Nipah virus first appeared in Malaysia in 1998 in peninsular Malaysia in pigs and pig farmers. By mid-1999, more than 265 human cases of encephalitis, including 105 deaths, had been reported in Malaysia, and 11 cases of either encephalitis or respiratory illness with one fatality were reported in Singapore.[21] In 2001, Nipah virus was reported from Meherpur District, Bangladesh [22][23] and Siliguri, India.[22] The outbreak again appeared in 2003, 2004 and 2005 in Naogaon District, Manikganj District, Rajbari District, Faridpur District and Tangail District.[23] In Bangladesh, there were also outbreaks in subsequent years.[24][8]

In May 2018, an outbreak was reported in the Kozhikode district of Kerala, India.[25] Seventeen deaths were recorded, including one healthcare worker.[26][10][27] Those who have died were mainly from the districts of Kozhikode and Malappuram, including a 31-year-old nurse, who was treating patients infected with the virus. Two of the infected were completely cured. On June 10, 2018, the outbreak was officially declared to be over.[28]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Signs and Symptoms Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "WHO Nipah Virus (NiV) Infection". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Transmission Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Diagnosis Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Prevention Nipah Virus (NiV)". CDC. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Broder, Christopher C.; Xu, Kai; Nikolov, Dimitar B.; Zhu, Zhongyu; Dimitrov, Dimiter S.; Middleton, Deborah; Pallister, Jackie; Geisbert, Thomas W.; Bossart, Katharine N.; Wang, Lin-Fa (October 2013). "A treatment for and vaccine against the deadly Hendra and Nipah viruses". Antiviral Research. 100 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.012. ISSN 0166-3542. PMC 4418552. PMID 23838047. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Morbidity and mortality due to Nipah or Nipah-like virus encephalitis in WHO South-East Asia Region, 2001-2018" (PDF). SEAR. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

112 cases since Oct 2013

- 1 2 3 "Nipah virus outbreaks in the WHO South-East Asia Region". South-East Asia Regional Office. WHO. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ CNN, Manveena Suri, (22 May 2018). "10 confirmed dead from Nipah virus outbreak in India". CNN. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Nipah virus outbreak: Death toll rises to 14 in Kerala, two more cases identified". Hindustan Times. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ "After the outbreak". Frontline. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Nipah Virus (NiV) CDC". www.cdc.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Luby, Stephen P.; Hossain, M. Jahangir; Gurley, Emily S.; Ahmed, Be-Nazir; Banu, Shakila; Khan, Salah Uddin; Homaira, Nusrat; Rota, Paul A.; Rollin, Pierre E.; Comer, James A.; Kenah, Eben; Ksiazek, Thomas G.; Rahman, Mahmudur (2009). "Recurrent Zoonotic Transmission of Nipah Virus into Humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (8): 1229–1235. doi:10.3201/eid1508.081237. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2815955. PMID 19751584. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S.; Hossain, M. Jahangir (2012). TRANSMISSION OF HUMAN INFECTION WITH NIPAH VIRUS. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 Islam, M. Saiful; Sazzad, Hossain M.S.; Satter, Syed Moinuddin; Sultana, Sharmin; Hossain, M. Jahangir; Hasan, Murshid; Rahman, Mahmudur; Campbell, Shelley; Cannon, Deborah L.; Ströher, Ute; Daszak, Peter; Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S. (April 2016). "Nipah Virus Transmission from Bats to Humans Associated with Drinking Traditional Liquor Made from Date Palm Sap, Bangladesh, 2011–2014". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (4): 664–670. doi:10.3201/eid2204.151747. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4806957. PMID 26981928. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Balan, Sarita (21 May 2018). "6 Nipah virus deaths in Kerala: Bat-infested house well of first victims sealed". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Bossart, Katharine N.; Rockx, Barry; Feldmann, Friederike; Brining, Doug; Scott, Dana; LaCasse, Rachel; Geisbert, Joan B.; Feng, Yan-Ru; Chan, Yee-Peng; Hickey, Andrew C.; Broder, Christopher C.; Feldmann, Heinz; Geisbert, Thomas W. (8 August 2012). "A Hendra Virus G Glycoprotein Subunit Vaccine Protects African Green Monkeys from Nipah Virus Challenge". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (146): 146ra107. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004241. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 3516289. PMID 22875827. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Vigant, F; Lee, B (June 2011). "Hendra and nipah infection: pathology, models and potential therapies". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets. 11 (3): 315–36. PMC 3253017. PMID 21488828.

- ↑ Broder, Christopher C.; Xu, Kai; Nikolov, Dimitar B.; Zhu, Zhongyu; Dimitrov, Dimiter S.; Middleton, Deborah; Pallister, Jackie; Geisbert, Thomas W.; Bossart, Katharine N.; Wang, Lin-Fa (October 2013). "A treatment for and vaccine against the deadly Hendra and Nipah viruses". Antiviral Research. 100 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.012. ISSN 0166-3542. PMC 4418552. PMID 23838047. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, Ksiazek TG, Mishra A; Comer; Lowe; Rota; Rollin; Bellini; Ksiazek; Mishra (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ Eaton, BT; Broder, CC; Middleton, D; Wang, LF (January 2006). "Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 4 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1323. PMID 16357858.

- 1 2 Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L (2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- 1 2 Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD (2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (12): 2082–7. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701. PMC 3323384. PMID 15663842. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Arguments in Bahodderhat murder case begin". The Daily Star. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Bever, Lindsey (2018-05-22). "Rare, brain-damaging virus spreads panic in India as death toll rises". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- ↑ "Lini Puthussery: India's 'hero' nurse who died battling Nipah virus". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "After the outbreak". Frontline. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ↑ "Nipah virus contained, last two positive cases have recovered: Kerala Health Min". The News Minute. 2018-06-11. Retrieved 2018-07-10.